The following article was submitted to the Journal of the Federated Institutes of Brewing in 1931

BARLEY TRADE OF THE BIBLICAL AND EARLY TIMES.

By S. K. Thorpe.

Barley is generally admitted to be our oldest cultivated grain, and it is believed that wheat was introduced into this country by the Romans in B.C. 54, and, for some time after that it seems probable that barley was the staple food-grain. This point is brought to our notice by the large number of old words and place-names, having reference to barley. Thus, the word “barn” is a corruption of the two Saxon words Baere = Barley and Ærne = House or Store. It seems somewhat out of place to hear a tram-car conductor, on his last journey, say that he is taking his car into the “Car barn.”

Barton, as a place-name, occurs in all parts of the country, and is still used in Lincolnshire to denote a farmstead lying some distance from a village. Before agricultural land was enclosed by hedges or stone-walls, the open country was called “the Field”; the land surrounding the village was enclosed, and called a “close,” or enclosure, or a ton. Plots of barley grown in the open “Field” were harvested, and carted together in stacks, and then protected by a ton, or tun, or enclosing fence. When it became necessary to have a herdsman and a plough man’s cottage erected near the barley enclosure to care for the cattle and horses which were fed at this enclosure, it was called the “Barton,” i.e., Bere = Barley, Ton = an enclosed fencing; hence our present-day places of BARTON-on-Humber, Barton under-Needwood, etc. Barnstaple was probably the staple, or market at which the barley was sold, or marketed, when it was collected into barns.

Berwick was the Baere, Wick, or Barley village, or possibly the Scandinavian settlement from which the Vikings exported barley. It is curious that where we have Baere in place-names, and such places have remained purely agricultural, they are in many cases on land which is today favourable for growing barley, e.g., Berwickshire, Beer in Devonshire, Bearley in. Warwickshire. The absence of Baere place names in Norfolk is noteworthy, and we can only assume that Norfolk gave its names to the villages before barley was generally cultivated.

Bigg, or the six-rowed barley of Caithness and Sutherlandshire, was apparently brought there by the Vikings, from Iceland or Norway, and was probably not imported from the lowlands, or from England; the Iceland and Danish word for barley is still Bygg. When fruit is imported from the Canaries, we use the name by which they are called in their native country, i.e., Bananas, we do not call them “Golden Fingers”: when the Vikings landed in the North of Scotland, and planted the grain which they had brought with them, they still called it by their own name, i.e., Bygg, or Bigg. It would be of interest to learn if there are any places in the North of Scotland in which this word Bigg has become a place-name, as it has in England.

Devonshire has over 100 place-names containing Baere in them, but to jump to conclusions in place-names is a dangerous pitfall. At first sight, it would appear that Devonshire was once a great barley-growing country, but curiously enough, there are other similar words of Anglo-Saxon origin. Baere = a pasture or meadow, and Beare = a grove, but whenever the word Bere appears in the first part of the place-name, or alone, it seems to refer to barley, as in Beer, Bearley, Bere Alston and Bere Ferrers, but in Kent is beare it is a meadow, and again, Ivigbeare means “the village in the grove covered with ivy.”

Berwick, in Sussex, also takes its name from Baere, or Barley; the suffix “Wick,” as applied to place-names, has two distinct origins: —

- as in Berwick-on-Tweed, Ipswich, Harwich, Wick, etc., it denotes a Scandinavian settlement, on an inlet from the sea, or estuary of a river.

- as it occurs in Berwick (Sussex), Droitwich, Wickham, etc., and most inland places is of Saxon origin, and denotes a village, thus Droitwich means “the dirty village.”

The old lineal measure—three Barley corns = one inch—is well known, but on the authority of the Encyclopedia Britannica this was subsequently changed to four Barley-corns = one inch in certain districts of the country. This would probably come about at the time when bere or the six-rowed barley, common in Saxon times was being replaced by the two-rowed barley (called by the generic name of Chevallier) and the time when this change took place and the time when this change took place would probably indicate the period when would probably indicate the period when Chevallier barley was generally being adopted, instead of winter or six-rowed barley.

Most text-books on brewing give the word Beer as being derived from the Dutch or German word Bier, but it seems more probable that the word comes from Baere, the plant grain from which the beverage was made; this would conform more to Anglo-Saxon and Celtic origin of names. Thus, Stitchwort was the plant from which they made a wort, or solution to cure the stitch; Liverwort was similarly named because it was used to make a medium for treating the liver. The word “wort,” still used for the unfermented solution of malt, is probably as old as brewing, and seems to imply that beer is made from the solution of the plant or grain Baere.

It seems highly probable that the Vikings may have taken our Bare over to Flanders or Denmark, and that the German and Dutch word “Bier” may have been derived from the original barley, or Baere grown in this country; they would call it by the name by which it was known in this country, from where they had obtained it. It is, however, possible that our word “Beer” may have come to us via Holland, or Germany, although originating in this country.

Wheat. — There are relatively few words and place-names referring to Wheat, which is the same word as White. Both words were originally pronounced as though the H preceded the W, and to this day, a Lincolnshire agricultural labourer will refer to a field as growing a crop of HWE-AT, which is probably the old pronunciation. With the solo exception of Germany, no other country has a name for this grain at all similar to Wheat. There are only a few place-names in this country referring to Wheat, such a Whiteacre, Whatcombe, Whitcombe, and Whaddon (and probably Waddon), but Wheathampstead has nothing to do with wheat, but is named after a Dane called Whatama, and is a corruption of “Whatama’s Homestead.”

One Reason why Moses Instituted the Pass-over. — To go further back to Egyptian and Biblical times, we find evidence of barley being the chief grain crop, and there are more frequent references in the Bible to barley, than any other grain. When we get Biblical references to wheat, it was probably what we should now call “Spelt” or “Emmer,” a grain more elongated than our present-day wheat; in appearance, it is half way between rye and wheat. It would seem that the “fine” meal referred to in the Bible, was made from “Emmer,” and was only consumed by the elite of the population, and that the ordinary meal (Gen. xviii., 6; Levit. ii., 1) was made from barley. There thus becomes a nice distinction in making a Thank-offering of “Fine” meal, which entailed a greater and more costly sacrifice than an ordinary “meal offering” (Numbers v., 15—11. Kings iv., 41).

The Egyptians were beer-drinkers (cf. J. F. Gretton, this Journ., 1929, 356), and it seems probable that when the Israelites were working as slaves in Egypt, they were served with beer as part of their rations, or, at any rate, it was in every-day consumption. Egyptian beer was made from fermented barley-dough, and the making of beer and bread were carried on together, being considered only as different parts of the same occupation.

On the authority of Father Ubach, head of a well-known Monastery at Jerusalem, beer must have been known to Moses; indeed, if proof of this were necessary, we have only to turn to the fact that the Hebrew and Egyptian languages have four or five different words, such as “Seor,” “Shikur,” “Boosa,” “Metzmeth” which referred to beer, fermentation, or leaven. It would be as idle to think that beer was not used in Moses’ time (when we find these words in the language of the period) as it would be to argue that the Red Indians were vegetarians, when they had several words for the different method by which they killed and roasted a buffalo.

We have heard of the teetotaler, who was so strict in adhering to his principles, that he refused to drink milk, if the cows had been fed on brewers grains, for fear he should be taking alcohol, but if he adhered strictly to his principles he would be more correct in refusing to eat bread, as the ordinary quartern-loaf, when put into the oven, contains about one-fifth as much alcohol as a double-whiskey, and although most of this is evaporated during baking, ordinary household bread is not absolutely free from alcohol.

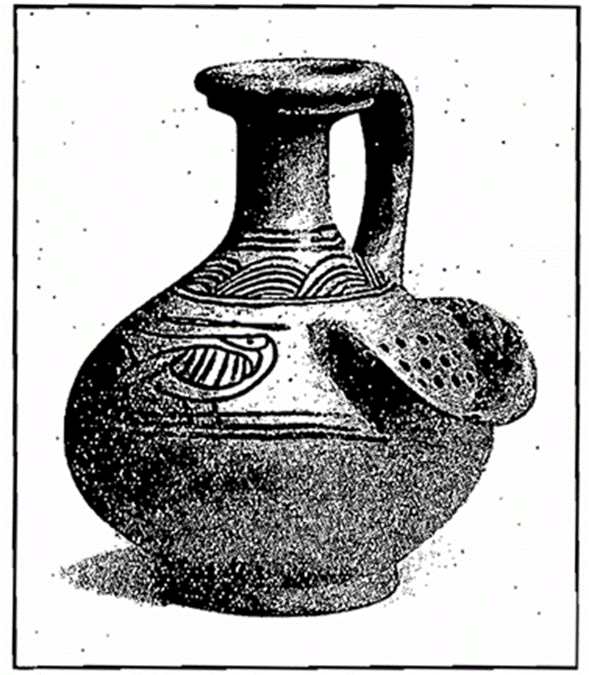

The dough for making beer was allowed to ferment until it had become highly alcoholic; it was dried in the sun, and then crumbled into a special mug, and water was added to it, which absorbed the alcohol. The beer, or “booza,” was poured off through the perforated outlet, which kept back the crumbled bread, and no doubt filtered the ” booza,” so that it would be nearly bright and slightly acid when poured off. ” Booza ” made in this way, will contain about 6 per cent, alcohol, and will be drinkable for about 4 to 5 days after making, but it becomes very acid after this time.

The Passover. — Many admirable sermons have been preached on this ceremony, which Moses instituted about 3,000 years ago; it is still most strictly and religiously kept by all orthodox Jewish families, and is the basis of the ritual of the Communion services of all Christian churches. It should be borne in mind that when Christ instituted this service 1900 years ago, He was “Keeping the Passover” which Moses had inaugurated centuries before.

Many reasons are even now being found for the laws which Moses made, and it is probably no over-statement that modern European civilisation rests more on the Ten Commandments than on any other civilising influence.

There are two distinct Commands in the Passover: — Exodus xiii., 6, “Seven days shalt thou eat unleavened bread;” and Exodus xiii., 7, “Ye shall put all leaven out of your houses.”

This is not infrequently regarded as a repetition, or emphasis, but according to the best authorities, the first refers to Bread, and the second to Beer, viz: — ” Thou shalt eat no leavened Bread, and thou shalt drink no Beer for seven days.” Picture to your minds the task which Moses undertook when he accepted the leadership of the Israelites, to bring them “out of the land of Egypt, and out of the house of bondage,” and put a modern construction on it. Moses had repeatedly demanded from Pharoah the release of the Israelites, which had been persistently refused, until Pharoah began to relax the conditions on which he would let them go. First, he conceded that they might go, and take their wives and small children, but when Moses demanded that they should also take their flocks and their herds, their asses, cattle, sheep and goats, Pharoah refused, and it was not until Moses had killed the first-born of all the Egyptians, that Pharoah sent for Moses and Aaron, and told them to depart, and to take their flocks and herds with them.

Moses was evidently prepared for this, and took Pharoah at his word; he had ordained the Passover the night before, so as to give everyone a heavy meal of lamb or goat meat before starting on their journey, not knowing when they would get their next meal, and so that they should not suffer with indigestion, he had ordered them to eat it with “bitter herbs,” which was most probably horse-radish.

Moses had to supply the transport and commissariat for a moving army of about 8,000 people (estimated at 6,000 Israelites, and 2,000 camp-followers). He had arranged his asses for his transport, his cows and goats for his milk supply, his sheep for his meat supply, and every man had to carry with him his own clothes and his own kneading trough, wrapped up in his raiment.

His grain supply was difficult; we are not told in the Exodus, in so many words, but it is there, and is referred to (Lev. xxiii, 15) as the “Wave offering.” The morning after the Passover, the whole congregation had to assemble, and according to Jewish tradition, everyone had to bring with him “An Omer of Barley.” This undoubtedly constituted Moses’s grain supply. It is still retained in the Jewish celebration of the Passover and is called “Counting the Omer.” Obviously, the barley supply was collected and carried on the backs of the asses. The asses, no doubt, also carried the Querns, or hand mills for grinding the barley, but every man had to carry his own kneading trough.

Moses was obviously afraid that the Israelites would want to start using his meagre grain supply for making beer, so he cut off their yeast supply; they found they had come out of Egypt without any leaven, so could not make beer.

When Moses started to persuade the Israelites to leave Egypt, he said he would lead them to a land of “milk and honey,” but we are told “the people harkened not unto Moses,” but when he told them he would lead them to a land of “corn and wine,” the people followed him. If Moses had told the Israelites, when they left Egypt, that they would not get any beer, they never would have followed him, but he provided them with barley, and then “someone had forgotten the yeast”; no wonder the people “murmured” at him.

When he led the people across the Red Sea (or reedy marches of the neighbourhood of Port Said), and arrived at Marar, the people murmured at him because the water was bitter, and they could not drink it, so Moses cut down a tree, and put its fruit into the water, and so made it sweet. On the authority of the Austrian agricultural botanist, Sprangel, the tree which Moses out down, was the locust-bean tree. This seems highly probable as being the way in which Moses overcame the difficulty with alkaline or bitter water, and also gave the Israelites the nearest substitute he could for beer.

Mr. G. C. Matthews has made some experiments with locust-beans, and will, I hope, give us his conclusions. Locust-beans may not carry a ferment on their husks similar to the vinous ferment, or “must” on grapes, but it appears that when cargoes of locust-beans arrive in this country, the hatches have to be left off for some minutes before discharge can commence, as I was told — “to let the alcoholic fumes escape.”

It is probable that the origin of why we have an “offertory,” or “sacrifice” or “collection” at the Communion Service today, is that Moses ordained this “collection” or “offering” of barley on the morning after the Passover, in order to obtain his grain supply ready for the Exodus.

Joseph’s Grain “Corner.” Many of you have no doubt read a novel recently published, called “The Coat of Many Colours,” which describes the everyday life of Joseph; how he was sold as a slave into Egypt, and succeeded in making himself Pharoah’s Prime Minister. At present, we know little of how Joseph succeeded in cornering grain, and keeping it seven years without it going weevily. The grain which Joseph stored was most probably barley, and we know that he had to “pull down his barns, and build greater.”

Some three years ago, Sir Flinders Petrie, discovered at Fayum in Egypt an old rush work basket, which contained a quantity of wheat (or Emmer) and barley, and also a number of personal ornaments, such as earrings, finger-rings and bracelets, etc., and also an old flint sickle.

Sir Flinders estimates these as being at least 6000 B.C., and most probably 10,000 B.C., and by his courtesy I have had a model made of this old flint sickle.

[Some of the grains of barley and Emmer found with the sickle were shown.] This raises the question as to how long the germinating power of the grain lasts. There is no foundation to the story which circulated some 50 years ago, that a seedsman had succeeded in growing wheat found in an Egyptian mummy. I am not aware that any barley has been known to germinate more than 12 years after harvest, (c.f. Baker and Hulton, this Journ., 1910,433.)

Discussion.

The Chairman (Mr. F. Sims) said they had listened to two very interesting papers. It seemed to him that brewers would have difficulty in obtaining Californian barley for brewing purposes in years to come, if the author’s prophecy held true, in which event it would be necessary to re-organise their ideas. The tendency to send so much money to America every year for the purchase of barley was unfortunate, and it was a pity there was no regular supply forth coming from the Colonies. North African and Smyrna crops could not be relied upon as a rule as they contained so much dirt; the Australian six-rowed barleys were very badly threshed.

Mr. H. E. Dryden said that up to a few years ago Californian malts generally yielded an extract of 88 to 90 lb. per qtr. A few years ago, there was a change in the type and the extract sometimes reached 95 lb. Some of the 1930 crop yielded an extract as high as 98·4 lb. per qtr. Obviously, such a malt would contain loss husk and consequently be poorer drainage material as compared with the old type of malt. It would become a question whether the new type of Californian should not be considered as heavy malt when making up the grist.

Mr. H. A. Vasse said that if America gave up Prohibition it seemed that from Mr. Thorpe’s figures that that country would not be able to produce sufficient barley for themselves. He would like to ask Mr. Thorpe how much barley there was in an “omer.”

Dr. Slator said that the change in the type of the present-day Californian barley had been noticed by many. Mr. Thorpe, speaking from first-hand knowledge, had given the members an explanation which was not generally known and which was of considerable interest. Referring to alcohol in baked bread, Dr. Slator said that it was of importance in estimating these traces by distillation not to consider every substance lighter than water to be ethyl alcohol. The amount of alcohol left in a loaf of bread was minute. He also asked whether artificial manure was used in California now that farm horse manure was not available.

Mr. F. B. Buxton suggested that in order to keep away weevil it might be worth the trial of displacing the air in a barley store by carbon dioxide.

Mr. G. T. Peard asked if the author knew of any explanation of the fact that the Californian barley of recent years was altering steadily and showing higher extract and lower nitrogen. Was it due to a progressive migration of the barley growing district to the higher land already referred to? Would the author also explain how the”Standard” Californian barley for the year was made up?

Mr. A. C. Hinde said he thought a possible reason why weevil did not destroy the whole of the grain when stored in olden times was that the latter contained an excessive amount of fine dirt and was stored underground in practically air-tight containers. Although the first foot or so on top of the store might very easily be alive with weevil the underneath portion would be free, due he thought, to the carbonic acid produced by respiration.

Mr. S. K. Thorpe, in reply, said that an “Omer” of barley was about 2½ quarts: a “Homer” was about 5 bushels. So far as he had been able to trace an “omer” of barley was offered up by each man. He believed no artificial manure was used in California. Fields near the homesteads might get a little. Nine-tenths of the land got no manure.