CARAMEL AND STABILITY

Paper delivered in November, 1925

By H. W. Harman and J. H. Oliver, D.I.C., Ph.D., B.Sc.

Caramel has been used in brewing for a long time and has been the subject of a number of communications to the Institute.

The qualities demanded of a caramel arc well appreciated by brewers and were defined by Evans (this Jour. 1895, 1, 32) as: — (1) Permanent colour of desired tint; (2) the highest colouring power possible; (3) good flavour, and (4) solubility.

With regard to high colour and good flavour, however, it is well known that where a caramel is to be used in the copper for a black beer of soft sweet character, the colouring power of the caramel is limited, and it is with this class of caramel as used in the copper rather than with the high tinctorial caramels used simply for colouring purposes, that we are chiefly concerned in this note.

Lovibond (ibid 1900, 6, 306) published a detailed account of a method for the standardisation of colour for comparative purposes, and in the same year Salaman and Goldie (ibid 1900,6,561) drew attention to the methods of manufacture and to the effects of increasing alkalinity as giving increased colouring power, this being accompanied, however, by a tendency to formation of deposit after addition of the caramel to the beer.

Briant (ibid. 1912, 18, 673) dealt very fully with the subject of caramel and more particularly with the importance of nitrogen present.

In the course of the technical examination of caramels, we have occasionally observed that certain samples interfered with the stability of a beer, in both experimental and brewery fermentations. It is now generally accepted that a caramel should be acid to litmus. Occasionally a sample would be neutral or perhaps alkaline to the indicator, and an experimental fermentation showed that the alkaline samples produced beers which developed bacteria on forcing.

In view of the apparent relationship between stability and active acidity, it might be supposed that this was the primary factor in the use of alkaline caramels, and we have accordingly measured the active acidity in our experiments to determine whether there was any connection between this alkalinity and tendency to unsoundness.

In practice, a beer will resist contamination largely in proportion to the rate and quality of the hops used, so that to introduce what may be considered as normal infection into the worts, which were carefully sterilised before fermentation, we used samples of brewery yeasts from various sources.

Actually, we have reason to believe that although yeast may appear to be pure, its degree of infection varies sufficiently to render the control experiments slightly different as indicated by the deposit thrown down after the fermented sterile wort is forced.

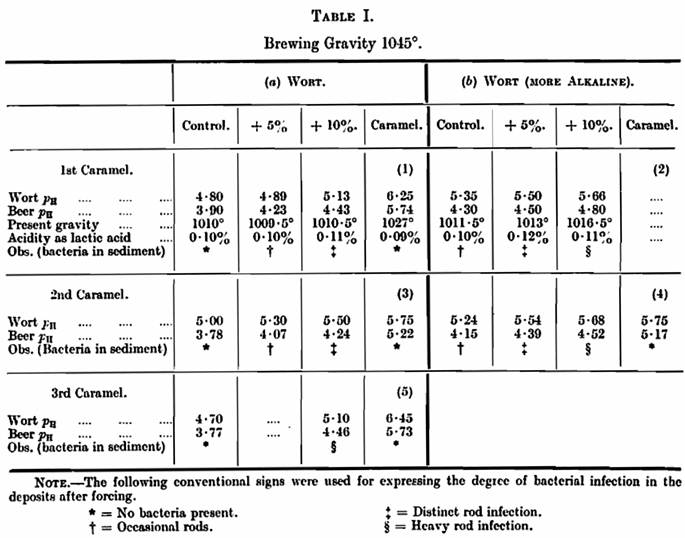

In the experimental fermentations, we set up controls of hopped wort of sp. gr. 1045° and treated it with additions of 5 to 10 per cent, solutions of the hopped caramel under examination at a sp. gr. of 1045°, the caramel also being fermented by itself.

The results, together with the pH at the beginning, and end of fermentation, and the observations on the deposits after forcing for eight days at 80° F. were as follows: —

Table I (2) and (4) are interesting in showing that the pH of the finished beers does not differ to any extent from those of the beer +5 per cent, caramel in 1 and 3, and it is to be noticed that the deposits from these beers approximately agree in their general appearance. The deposits from the fermented caramels, although of high pH figure, are very pure. While the pH conditions may be suitable for bacterial growth, other factors have interfered. The pH of a caramel as determined with a 15 per cent, solution may be as high as 8·4, the more usual figure for an alkaline caramel found unsuitable for brewing being 6 to 6·5.

The alkali used in their preparation may be either ammonia or caustic soda, and it might be supposed that in the case of the ammonia process caramels, which are the most commonly used of alkaline caramels in brewing, the alkalinity was due to the presence of free ammonia, but this does not seem to be very likely because we found that the addition of ammonia to wort to bring its pa back to that of a caramel resulted in a beer of normal pH after fermentation (Table II).

This capacity of absorbing ammonia exhibited by the yeast, suggests that the alkalinity of the ammonia process caramels which persists after a fermentation, is due to more elaborate nitrogen compounds.

It has been previously noticed (Laboratory Text Book—Briant and Harman) that the ammonia seems to be combined in some way with the sugar, and that this may be so is shown by the increased difference in pH between the control experiments and those containing caramel after fermentation when part of the sugar portion has been fermented away.

If these effects on the deposits were due largely to increased alkalinity, it would be expected that by correcting the alkalinity after the additions of the caramel, these deposits would disappear.

The experiments recorded in Table III illustrate the point.

It will be seen that the addition of acid gives a final beer comparable with the control, and this is associated with a satisfactory deposit after forcing. It is not, of course, suggested that a caramel should be treated in this way, but it certainly makes it quite evident that the objectionable

properties of such a caramel arc largely associated with its effect on the active acidity of the wort. Whilst these figures substantiate the claim of Parsons (ibid, 1924, 30, 45) that there is a distinct relation between the active acidity of a beer, and its behaviour on the forcing try, we have observed with the beers from different breweries that there is apparently no connection between the pH of the finished beer from the breweries and their relative stability. We are in agreement therefore with C. Ranken who has recently drawn attention to this point {ibid. 1925, 414).

Thus, in one particular case in a brewery with which we are connected, the pH of the beer at racking is consistently 4·1 to 4·15 whilst in another brewery the pH of the finished beer is 3·8 to 3·85, whilst in each case the stability of the two beers is equally good as determined by the usual methods. On the other hand, it might be expected that the beer of pH 4·1 would tend to suffer more from infection than a beer of pH 3·8. There are, of course, a number of interfering factors which must be taken into consideration, for example, the beer of higher acidity being the product of a fast fermentation whereas the less acid beer is produced on slow fermentation methods. Although this difference in method may contribute to the results found, it does not necessarily follow, because we have found in other breweries where a fast fermentation is preferred, that the resulting beers are more alkaline. It can only be assumed that as a result of experience the brewer has determined for himself the conditions of hop rate and liquor treatment and so on, which are the optimum conditions for the finished beer to possess sufficient antiseptic properties to enable it to resist the average contamination met with under his normal trade conditions.

Different breweries about the country meet with varying degrees of infection and empirically, with the active acidity of certain factors fixed such as liquor, malt, etc., they have arrived at suitable conditions of working which will ensure the necessary stability. It remains, however, an undoubted fact that for any one given brewer, any deviation—and possibly any small deviation from the normal active acidity towards alkalinity, results in a lowering of general antiseptic properties, and may yield infected beers.

Whilst the acidity as normally determined by titration is an indication of a loss in active acidity, reference to Table I will show that the variation may be so small as to remain un detected or may be accounted for by experimental error.

When an alkaline caramel is found to produce a higher pH value in the finished beer, the alkalinity operating throughout the fermentation may result in a smaller quantity of hop resin going into solution and alter the size of the colloidal particles, and this will inevitably produce a difference in the palate flavour of the beer.

During some experimental fermentations with worts made relatively excessively alkaline, we noticed a distinct alteration in the palate flavour of the beers corresponding with increasing alkalinity, until we reached the stage of a wort of pH 6·8 with resulting beer of pH 5·58 in which the palate flavour was almost exactly the same as the characteristic flavour of a yeast pressed beer. It is only reasonable to suppose that similar changes in the alkalinity have slight but quite noticeable effects on the palate flavour of the beers.

Conclusions.

1. Caramel which are neutral or alkaline to litmus may give rise to beers of unsatisfactory stability.

2. The pH of a 15 per cent. sol. (approx. sp. gr. 1045o) should not be more alkaline than 4·5 to 5·0. 3. The increased alkalinity may have an effect upon the palate flavour.

24, Holborn Viaduct, E.C. 1