MEETING HELD at the GRAND HOTEL, BIRMINGHAM, on Thursday, December 18th, 1902.

Mr. W. W. Butler (President) in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed: —

The Chilling and Filtering of Top-Fermentation Beers. Part II.

By N. Van Laer.

The subject of my paper for this evening is principally the treatment of beer in connection with the slow process of chilling. I propose to examine two methods of producing n sparkling bottled beer without the aid of carbonating. The manipulation to which the beer is submitted in these methods may be subdivided into two parts, i.e.: —

1. The natural process of conditioning.

2. The forced process of conditioning.

- The Natural Process of Conditioning

This is, to a certain extent, only successfully carried out when applied to beers which have been brewed with selected materials of the best quality. I must also add that the most suitable method of brewing must be carefully ascertained and the whole of the operations performed under favourable conditions. When this aim is attained, the boor at racking is generally extra hopped with choice Bavarians at the proportion of 8 to 12 ounces per barrel. The beer is then put into strong casks or vats and kept in a room, the temperature of which is uniformly maintained at about 55o F., and left to mature for a period varying from one to three months. During the secondary fermentation which takes place the beer becomes gradually charged with “carbonic acid gas.” In using the words “carbonic acid gas,” I shall base myself on the general opinion which inclines to the belief that the carbonic acid gas produced by the decomposition of the sugars is not liberated in the form of carbonic anhydride CO2, but in the form of the hydrate carbonic acid, H2CO3 i.e., H2O+ CO2 = H2CO3. We also know that the various species of yeast decompose the sugar with formation of small quantities of succinic acid, and acids of the acetic scries. These acids also com bine with the alcohol in the production of ethers, and it is these ethers which contribute to a large extent in giving to the beer that fine bouquet and aroma which characterises a well-matured bottled beer. When a good, sound, secondary fermentation has taken place, and none of the gas has escaped during the storage, the beer should contain a certain proportion of gas, the quantity varying, of course, with circumstances, and at times very much in successive brewings. In transferring the beer to a cold store, the gas enters gradually into solution, so that when the temperature has been reduced to about 32° F., a sample of the beer has the appearance of being quite flat. As it takes about two clays to lower the temperature of the beer to 32° F. when in cask, sufficient time should be allowed in order to obtain a satisfactory chilling, depositing, and clarification. From six to ten days is the average time required before the beer is ready for the filtering process. Naturally in this system, great care must be taken not to lose any of the gas during the manipulation it is submitted to. Against this method it may, of course, be said that it is not suitable for light beers of low gravity, as one experiences great trouble in getting them into condition, and, in some instances, runs the risk of seeing the beer deteriorate after a short time. Then, again, we must consider the cost and time and space it takes for storage and chilling. Besides, one cannot always rely on having sufficient gas produced during the after-fermentation to obtain the sparkling characteristic of bottled beer. In conclusion, it is only necessary to add that this system is very unreliable and also costly, in consequence of the long storage and chilling, especially if this is done in wood. I am therefore convinced that this process will not come into general use unless some improvements are introduced.

- The Forced Process of Conditioning.

The main object of this method is to force the beer rapidly into a vigorous after-fermentation by means of priming or by the addition of krausen beer. This treatment of beer is entirely of American origin. It was first applied to lager beers of the German type, then afterwards to several varieties of top-fermentation beers in the United States. As the krausening of beers is still, perhaps, comparatively unknown to British brewers, I think it worthwhile to quote hero the remarks on the use of krausen, given by Drs. Wahl and Henius in their 1902 edition of The American Handy Book of the Brewing, Malting, and Auxiliary Trades. Thus, on page 760, they say:

“Krausening.”

This consists in the addition of krausen beer, that is, young beer in the first or krausen stage of fermentation, 24 to 44 hours after pitching, according to pitching temperature and amount of pitching yeast used. As to the amount of extract and other constituents, it differs but little from fresh wort, hence it changes the composition of the ripened beer. While the addition of krausen beer will cause fermentation to continue in the chip cask owing to the presence of fresh yeast, all of the sugar introduced by it will not be fermented. The effects of krausening, therefore, are: —

“1. The krausened beer will have a higher percentage of extract, especially sugar. This has the effect of impairing the durability of draught beer, sugar being favourable to the growing of yeast.

“2. The krausened beer will contain a larger amount of hop resin; the taste of the beer is accordingly changed, krausen beer being sweeter on account of sugar and more bitter on account of hop resin.

“3. The krausened beer will contain more proteids which will impair the durability of bottled beer. Use sugar krausen for bottled beer.

“4. The krausened beer will contain a smaller percentage of alcohol.

“5. The temperature of the beer will be raised slightly owing to the revival of fermentation and the higher temperature of the krausen.

“6. Carbonic acid will be generated by the continued fermentation in the chip cask, which gas accumulates in the beer after bunging.

“7. Young yeast cells are added.

“The more energetic the cask fermentation, the more easily will the beer clarify. The young, vigorous yeast cells readily form clusters or lumps of yeast which will envelop, and, upon settling, carry down with them the smaller ones, together with bacteria and other suspended matters; thus, in part at least, promoting clarification.”

“Krausening is based on a principle similar to that which leads English brewers to ‘prime’ beer in the trade casks by adding a strong solution of cane or invert-sugar.

“Amount of Krausen.”

“This is governed by the properties desired in the finished beer. For shipping beers, draught and bottle beer (steamed), that is, beers of which durability is required, not more than 8 to 10 per cent. For common draught beer, 15 per cent, of krausen is generally used. These amounts vary, however, with the demands of the trade. In some cities as much as 25 per cent, of krausen is regularly added to the city beer.”

On page 774, Drs. Wahl and Henius describe the preparation of the sugar krausen as recommended by them in the above paragraph for bottled beer: —

“Sugar Krausen. —In 20 barrels of boiling water in hop, or rice kettle, dissolve 600 lbs. of anhydrous grape-sugar, boil for 15 minutes more, add 30 lbs. of fine American or imported hops, boil for 15 minutes more, run into hop-jack, and cool to 55° F. (10o R.), add 2 lbs. of yeast per barrel, and allow to come into krausen. (In about 24 hours a fine white foam will appear.) Now add to the beer in the chip cask 10 per cent, of this hopped sugar krausen, or 5 barrels per 50 barrels of beer.”

Krausening and priming is already in vogue in a few breweries in this country, but I understand that this process is only carried out by brewers who possess especially strong casks or tanks capable of standing high pressure. The experience of some brewers in dealing with beers that have been krausened with more than 10 per cent, of krausen, is that there is a tendency in the beer to take up a very pronounced yeast-bitter taste, accompanied by a certain rawness, which in many instances changes the type and character of the beer. In order to verify this point, I made a few experiments with quantities of krausen, varying from 5 to 20 per cent. The experiments, with proportions of from 5 to 10 per cent., were carried out on a large scale, i.e., on no less than one hogshead at a time. The krausen for this purpose was taken from a beer of the same type and original gravity as that to which the krausen was added, and taken 36 hours from the time of pitching. The experiments with larger amounts of krausen were conducted on a small scale, and in especially strong bottles. The beer in hogsheads was treated with 10 per cent, of krausen, and kept for 15 days at 58o F., afterwards chilled for the same length of time, filtered, and bottled. A few bottles were kept for observation; and on careful tasting, no after-flavour of krausening could be detected, and on sending the same beer out to the trade, no complaints were received. With regard to the laboratory experiments with larger quantities of krausen, the results were not so satisfactory, the beer with 15 per cent, presenting the symptoms of yeast-bitter taste and rawness as described above. I now pass on to some further experiments on the krausening and priming of beer, made with the object of finding the respective quantities of each of these required to produce an amount of carbonic acid gas practically equal to that contained in a beer carbonated in the usual way.

The first experiments were to find the exact amount of CO2 in carbonated beer in brisk condition as supplied commercially.

Carbonated beer in the trade contains: — 1,421 c.c. CO2 per litre; 1·4 volume per volume of beer, or 0·2752 grams per cent.

Extra carbonated beer: 1,530 c.c. CO2 per litre; 1·5 volume per volume of beer, or 0·2949 grams per cent.

Experiments with Krausen.

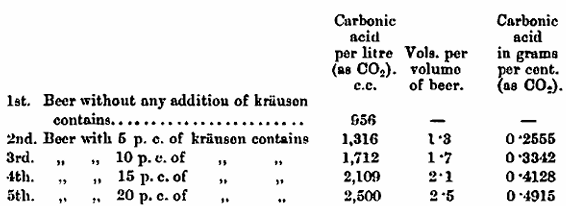

For this purpose, a number of strong bottles were filled with a light gravity beer (1045 sp. gr.), and to each of these krausen was added in the following proportions: —5, 10, 15, and 20 per cent.

The bottles, treated in the above manner, were left for a fortnight in a room of which the average temperature was 58° F.

The krausen for these experiments was taken 38 hours after the time of pitching from a beer of the same original gravity as those to which it was added. The specific gravity of the krausen was 1033.

Other bottles without any addition of krausen were placed under the same conditions of time and temperature.

These are the results of the experiments: —

The above figures show that an addition of 10 per cent, of krausen produces more carbonic acid than is contained in an extra-carbonated beer of the trade.

Experiments with Priming

The experiments were carried out under the same conditions of time and temperature as in the case of the krausen, but instead of a definite percentage of sugar being used, priming syrup of a sp. gr. of 1150 was added at the rate of 1, 2, 3, and 4 pints per barrel, and gave the following results: —

The addition of 2 pints of priming per barrel would therefore give the necessary condition. The analysis shows that each pint of priming produces about 300 c.c. of carbonic acid per litre. By theoretical calculation 346 c.c. is formed.

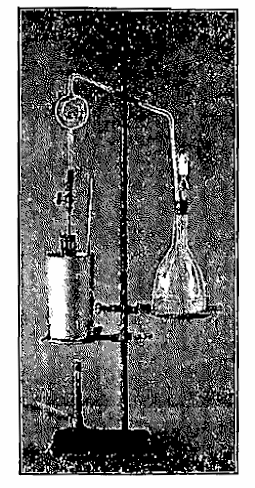

As no method of estimating carbonic acid gas in beer can be found in our present books on brewing, I will add a short description of a simple method devised by Mr. C. J. Flamen, of Burton-on-Trent: —

To establish communication with the interior of the bottle, a cork borer of about 3/16” diameter is used. It has one or two holes about 1½ inches from its cutting edge and a tap at the top. The bottles, if not corked, have to be closed with a specially-prepared screw stopper. This is made by drilling a 3/8 inch hole through the length of an chonite, or in preference, a lignum-vitæ stopper, and plugging this up with a cork; if thought necessary, a drop of sealing-wax on the bottom end makes everything secure. This stopper is used instead of the ordinary stopper at the time of bottling, or should this be not possible the bottle is left in the cold store at freezing temperature for a few hours, when the ordinary stopper can be replaced by the prepared ono without loss of gas.

The illustration shows the apparatus complete. The bottle of beer under investigation is placed in a water-bath filled with cold water, the cork-borer having been inserted with the tap closed. Connect with the tube leading to the absorption flask, which contains 100 c.c. of pure liquid ammonia (strong). The cork of this has an opening to allow of the exit of air, which passes through a tube containing glass wool, moistened with a few drops of ammonia to retain any trace of carbonic gas which might escape absorption. Tho tap is gently opened to allow the gas to escape, and the water-bath is then heated very gradually to boiling, so as to expel the last traces of gas from the apparatus by the alcohol vapour. The ammonia is then poured into a beaker, the water used to rinse the flask and the glass-wool being added, heated to boiling and precipitated by a solution of calcium chloride. Allow the calcium carbonate to deposit, filter off the ammonia,

boil the precipitate with several portions of distilled water, passing these through the filter, till all the ammonia is expelled. Add the filter paper, with the portion of precipitate adhering to it, to the portion in the beaker, add water and a known excess of sulphuric acid (normal), boil and titrate back with N/1 soda, using phenolphtaleine as an indicator.

The volume of liquid in the bottle is found by placing a file mark previously at the level of the beer, filling afterwards with water and measuring. There is very little trouble with frothing, but, if possible, bottles having a fair amount of space between the liquid and the stopper should be chosen.

Let us now consider for a moment a few of the advantages derived from krausening. As previously stated, and according to Drs. Wahl and Henius, it is not advisable to use more than 8 to 10 per cent, of krausen for bottled beer, in which durability is required. I must say that there is really no need to exceed this quantity of krausen. From experiments and investigations on this matter, I must repeat that 10 per cent, of krausen can be used with safety without changing the character of the finished beer and with production of sufficient natural gas to render the beer gaseous. Krausen has the advantage over sugar priming that it costs practically nothing, as a quantity of krausened beer of the same original gravity is added to the finished one, therefore the gas is produced without any further expense than that of the manipulation it is submitted to. As there is a tendency among the British public to take to a natural gaseous beer, it is of importance that brewers should be prepared in the event of competition forcing them to produce a beer of this description. Where a brewer possesses tanks (closed) for conditioning and chilling, the krausening is easily carried out; all that is required is to arrange the brewings so as to have the krausen always ready when wanted. The krausen can be either run direct into the tanks by gravitation, forced in by compressed air, or simply by pumping.

It is advisable, when dealing with tanks, to introduce the krausen in such a manner that it does not get mixed with the beer, but remains at the bottom of the vessel by difference of gravity. By using a pipe to go nearly to the bottom of the tank, the krausen will sink, and its gravity being higher than that of the beer, it will remain under the bulk of beer while fermenting, consequently the gas as it is generated, will travel through the mass of beer and enter in solution without necessitating any agitation. Having so far dealt with the priming and krausening in conjunction with the forced process of conditioning, ray remarks on this system would not be complete without saying a few words as to the means of clarifying the beer prior to filtration. As it is of the greatest importance to have the beer bright before filtration, it is necessary to have recourse to artificial means of fining. This is generally done by fining the beer at racking with ordinary gelatine finings, so as to let the beer drop fine while it is undergoing the chilling. I must acknowledge that I do not advocate this mode of clarifying beers for filtration, and in saying so I must endorse the following remarks published in the Brewing Trade Review, of September 1,1902, which read as follows: —

“Our Crude System of Clarification.”

“There can be no doubt, in our opinion, that within the next few years, in spite of our natural conservatism, the filter will have to a very considerable extent superseded isinglass finings, especially in the private trade. We admit the extra expense, but the demand for small bulks of immediately consumable beer is undoubtedly very pronounced, and advantage is already being taken of it by our more progressive producers.”

It is well known that finings are detrimental to the filtering medium, especially if the latter consists of a cellulose pulp, or a mixture of fine asbestos fibres with cellulose.

A serious drawback against this practice of fining is that when large quantities of beer arc filtered in one day, the filtering mass becomes thickly coated with finings, and to such an extent that the filtering capacity is very much reduced. In addition, it is not an uncommon occurrence to see particles of finings actually pass through the filter and settle in the bottles soon after bottling.

But, it will be asked, if finings are detrimental, what must be done to obtain a beer bright before filtration? To this I will answer, make use of the clarifying action of chips, which is purely mechanical. They act by superficial adhesion, their large surface attracting the yeast cells and the small particles in suspension, which, clinging to the chips, effect rapid settling and clarification. The employment of chips has sometimes been reviewed in the English brewing organs, but I am not aware that they have ever been tried on top-fermentation beers of this country. I really do not see why the clarifying action of chips should not be applied to beers treated by the chilling and filtering process. Those who are interested in this direction will find a deal of valuable information on the subject in Drs. Wahl and Henius’s American Handy Hook of Brewing. An extract from these authors’ work may prove of service in the treatment of beer by chips.

“Clarifying Chips.”

“They consist of strips of well-seasoned wood of varying length, width, and thickness, which are cut by suitable machinery from wood which is easily split. Beech and maple are the woods used almost exclusively for this purpose. The length of the chips varies between 6 and 12 inches, the thickness being about one-twelfth of an inch on an average. Chips also vary in form. There are smooth chips and corrugated chips, the latter showing either a uniform wave, or a pronounced fluted surface. Some brewers prefer smooth, straight, and thick chips, while others think the thinner corrugated chips are better. Of late, metal chips, particularly aluminium ones, have been introduced. In view of the fact, however, that certain metals are known to be capable of causing turbidity, caution must be observed in using metal chips.”

From this abstract from Drs. Wahl and Henius’s book, it is interesting to know that aluminium chips have been introduced of late. Unfortunately, these authors have omitted to give more information on the subject. In perusing the continental brewing organs, I came across an article on this subject by the late Professor L. Aubry, published as far back as 1894. In the Zeitschrft für das gesammte Brauwesen (vol. XVII, p. 155), Professor Aubry describes the aluminium chips as being composed of strips of aluminium in the form of a furrow 50 centimetres long and 4 centimetres in width. Their weight is 15 grams or 66 to the kilogram, while those made of wood and with the same dimensions weigh 25 grams or 40 to the kilogram. From these observations we gather that in taking even weights, the aluminium chips give a very much larger clarifying surface than those made of wood, moreover, 9 kilograms of wooden chips absorb about 0·7 litre of beer, while no absorption takes place with aluminium chips. Professor Aubry goes on to say that practical experience has demonstrated that for a vat of a capacity of 12 barrels, 2 kilograms of aluminium chips are required, the clarifying action of these chips being equivalent to 9 kilograms of hazelwood chips. Their adhesive properties are as good as the wooden ones, and they have the advantage of being easily cleaned and not liable to infection. It is very interesting to learn that the beer fined by this process does not give the slightest taste of aluminium, and from precise analytical researches with regard to the latter, it has been proved that no aluminium was dissolved by the beer. The conclusion to be drawn from the above, is that aluminium chips seem to possess similar fining properties to those made of wood. It remains to be proved if their economical conditions are in relation to the advantages they are supposed to afford. We may perhaps, someday, obtain more practical information from those brewers who have had experience with them.

I would like to enter into some practical details of the employment of wooden chips, such as the preparation they have to undergo before they can be introduced into the beer. Then, there is also a deal to be said about the chip cask, the glass enamel chip tanks, and the chip cellar To deal with these few questions would take up too many pages in this paper; I will, therefore, content myself by saying that the subject of chips deserves further investigation at the hands of practical brewers. I have so far touched on the means by which we can produce: —

1st. The natural carbonic acid gas.

2nd. The clarification prior to filtration.

I will now give a brief sketch with some practical details as to the working of such a system. First, I must point out that there are a few essential factors to be considered with respect to the storing, and chilling of the beer. The first item is, of course, suitable tanks to stand high pressure, and made of such a metal that will not have the slightest detrimental effect on the composition of the beer. This important requirement has been satisfied by the introduction of the glass enamel tanks, which are to be found in a number of breweries in this country. These storage tanks are admirably adapted for the krausening, or priming, and clarification. The complete process of conditioning, clarification, and chilling can be worked in the same tanks, providing that the latter are furnished with proper cooling arrangements. If this desideratum is fulfilled, the beer could undergo the whole treatment in the one vessel, thereby saving a great deal of labour, waste of beer, and loss of gas. If the storage plant or situation of the tanks does not lend itself to chilling in bulk, then some modifications and a combination of intermediate chilling would be required to overcome these difficulties. In other words, and to make myself a little more explicit, we will suppose that it is entirely impossible to chill the beer in the tanks after the production of carbonic acid gas, and partial clarification, then we are under the necessity of chilling the beer in some other receptacle. This drawback, if I may so call it, can again be remedied by passing the beer through a rapid chiller such as, for example, the “Deckebach” cooler. In this apparatus, the beer can be chilled to any desired temperature, and this without loss of carbonic acid gas, or waste of beer. From the “Deckebach” cooler, the beer is led to the storage tanks, where its temperature is uniformly maintained at 30° F. for another few days if desired. It may be said, speaking generally, that the time required in working on this system is about a fortnight, which is made up as follows: —

We see from the above table that by this process a natural gaseous bottled beer can be put on the market within 14 days. If space allowed, I could dwell on the advantages of this process at some length; I must however limit myself to saying that, notwithstanding some inherent defects, this system has found many ardent advocates among brewers, and is especially valuable for countries in which it is difficult to secure compressed carbonic acid gas.

Discussion.

Mr. W. Duncan said that he had unfortunately only heard the concluding portion of Mr. Van Laer’s interesting paper, but deduced that he had given a clear description of the process recently adopted in this country for the forced conditioning, chilling, and filtration of English beers. He would like to hear Mr. Van Laer’s opinion as to the relative flavour and stability of beers bottled by the process described, as compared with beers conditioned in and filtered from cask, as his own experience was that beers from the wood were distinctly superior in warmth of flavour, stability, and permanency of condition. With respect to the proposal to employ “chips” as a preliminary fining agent, would not their use remove very desirable flavouring constituents from the beer? Practical brewers fully recognised the inferiority in flavour of beers drawn from a new cask, and he was of opinion that when chips, washed each time, were employed, their use would tend to destroy the character of the beer. The process of beer chilling and rapid bottling had no doubt come to remain, but in considering different methods it was of just importance that their influence on the flavour and stability of the produce should not be overlooked. In regard to the quick and slow chilling processes, he thought the slow method altogether preferable, as deciding increased stability with reduced deposit. He thought it probable that the slow process with the gradual sedimentation of the precipitated matters determined reduction in the number of organisms and favoured more satisfactory filtration. He had seen the results of beer bottled by the ordinary syphon process, after the beer had been allowed to drop bright in the cold store, and there could be no question as to the reduction in deposit and preferable palate of beers bottled in this manner. He would like to know if Mr. Van Laer had experience as to the two methods of chilling and relative stability of the treated beers.

Mr. Van Laer, in reply to Mr. Duncan, said that by the process he had described, the flavour of the beer was not materially affected so long as the krausen for the conditioning was taken from a beer of the same type and original gravity, and that the amount did not exceed 10 per cent. As to the priming system and the quantity recommended, speaking from practical experience, he could say that the change in flavour was hardly perceptible, or if it was slightly altered, it was for certain classes of beer often an advantage. With regard to the question of conditioning in casks or cylinders, the natural process of conditioning was intended to be carried out in cask. But, as this process was troublesome, unreliable, and costly, he gave the preference to glass-enamel tanks. He was of the same opinion as Mr. Duncan that the slow process of chilling was the best for English beers. The slow process of chilling had the advantage over the rapid process that beers produced under the former system had superior keeping qualities to those which were produced by the instantaneous or rapid way of cooling. Some years ago, he undertook a number of experiments with the object of ascertaining the respective stability of beers treated by the instantaneous and slow processes of chilling. He came to the conclusion that beers treated by the rapid process, kept for about one week only without throwing a sediment, whilst those treated by the slow process did not show any sediment within one month to six weeks. Therefore, the stability of beer produced by the slow process of chilling was in every respect superior to that of beer produced by the rapid method of chilling. Mr. Duncan said he presumed the stability varied with different types of beer. Had Mr. Van Laer any results indicating the influence of different methods of brewing, with special reference to the mashing system employed? Mr. Van Laer said that naturally the stability varied very much with the type of beer. The experiments he had referred to were carried out on a large number of beers of different varieties. With regard to the question of brewing, he said that he had no special results to communicate.

Professor Adrian Brown said that he had listened with great pleasure to the paper. It formed a continuation of a previous communication by the author on the same subject, and in the discussion following the reading of that paper, the general impression amongst the speakers was that cold filtration was rather a fanciful sort of method which would not be adopted. This was only about two years ago, and now one saw how very much the system had taken hold, and was being employed by many of the large brewers. He would like to ask, with regard to the total amount of carbonic acid gas produced in Mr. Van Laer’s experiments, whether the 956 c.c. given in the tables represented the amount of carbonic acid gas at the commencement of the experiment? He thought the figures in the tables were exceedingly interesting, as they gave useful information regarding the amount of carbonic acid gas they required in cold filtered beer of good character.

Mr. Van Laer, in reply to Professor Brown said, that the figure 956 c.c. he had quoted referred to the natural carbonic acid gas in the beer before the experiments were undertaken. In deducting this quantity from that produced by krausening or priming, the amount of carbonic acid formed in the conditioning was arrived at. In using the term ” carbonic acid gas ” in connection with this mode of conditioning, he had done so in order to differentiate it from beers artificially charged with CO2.

Professor Brown enquired if Mr. Van Laer had determined the approximate temperature at which ice formed in beers of ordinary gravity. Of course, the temperature must vary somewhat with the amount of alcohol and solid matter in the beers.

Mr. Van Laer replied that he had frozen beers on several occasions; this was done in bottles, and the beers submitted to freezing were light dinner ales, pale ales, and certain mild ales of low gravities. The freezing point of these varied a little, and on the average ranged between 26° and 29° F.

Mr. W. R. Wilson said that Mr. Van Laer had mentioned two methods of krausening, one to make a special priming mixture consisting of sugar, yeast, and hops, and the other to take some of the beer out of the fermenting vats and use that as krausen. The simpler way was the latter one, and he would like to know whether the other method had any special advantage? It seemed to him they were going to extra trouble needlessly, to make special krausen, if their ordinary beer would do just as well. With regard to the subject of filters, one of the difficulties he had noticed was that they did not give a consistent product. Sometimes they found their filter giving them a beer which though bright, when examined was found to give perhaps 200 or 300 yeast colonies per c.c. of beer. They had no method, so far as he had seen, of packing it with a constant amount of filtering material. There were American filters which claimed that they were packed in such a way as to secure a constant quantity of filtering material, and he would like to know whether they gave more consistent results than the ordinary filter.

Mr. Van Laer, in reply to Mr. Wilson, said that the special sugar priming he had mentioned was an American preparation, which was specially recommended for fine delicate beers in which durability was required. He had suggested this process for those brewers who could not or did not wish to work on the krausening system. Concerning the amount of filtering material, it was essential that the filter chambers should contain the right proportions of pulp for which these were made. If the filter was insufficiently packed, there would always be some trouble in getting the beer brilliant. As to the amount of pulp having an influence on the number of cells left in the filtered beer, he had not gone into this question, but, of course, a great deal depended on the nature of the beer, and also on the composition of the pulp and the manner in which it was treated. If a pulp was not properly washed and sterilised, a marked difference was soon notice able in the stability of the beer.

Mr. Robert Clarke asked, with regard to the krausen, how many hours should be allowed to elapse after pitching before taking wort to be used as krausen out of the fermenting tun?

Mr. Van Laer said that the period varied from about 36 to 44 hours.

Mr. Clarke said that would probably be when the wort was beginning to throw up its head. He would like to ask if Mr. Van Laer advised a small quantity of priming if the old fashion of bottling was carried on?

Mr. Van Laer said that a small quantity of priming would be beneficial if these beers were intended to undergo a rapid conditioning.

Mr. Clarke inquired if the author found it gave a deposit.

Mr. Van Laer said that a deposit would be formed, the amount of which would naturally vary according to various circumstances. If a small quantity of priming were used, it would induce cask conditioning; and if the beer were bottled after this was over, it was likely that not much deposit would be formed afterwards so long as the beer was sound.

Mr. W. P. Harris said there seemed to be some considerable difference of opinion regarding the conditioning vessels; firstly, respecting the material used for their construction (whether it should be wood or metal), secondly, whether the vessels should be large or small. Mr. Van Laer had shown very clearly that a definite quantity of priming or krausen was capable of producing the desired amount of gas to enable the beer after conditioning, chilling, filtering, and bottling to exhibit all the necessary brilliancy and spark ling capacity. In dealing with ordinary trade beers it was a well-known practical fact that beer in large casks conditioned more quickly and maintained that condition for a greater length of time than the same beer in small casks; this was probably owing to the fact that if shive or bush leaked, or if leakage occurred through any other defect in the cask, the loss on the small cask was out of all proportion to the amount of beer the cask contained. Remembering that any loss of gas through defective vessel meant the use of extra priming or krausen to replace the amount of gas lost, would it not be far preferable to condition in large bulk rather than in casks, more especially when the commercial aspect of the question was considered, for the loss of gas and actual beer when dealing with casks was, as compared to it in tank, out of all proportion. He would like to know whether Mr. Van Laer had any experience with varying sizes of casks and tanks, and whether he had not found it more economical to use largo bulk in respect both to quantity of priming used and amount of beer actually obtained in bottle.

Mr. Van Laer said that in speaking from the point of view of capacity of the conditioning receptacle, he agreed with Mr. Harris that there was still some diversity of opinion on this matter. The conditioning in casks, and especially in small ones, was indeed a source of trouble, and undoubtedly the loss in gas (not speaking of the beer) in the manipulation was sometimes very large. But this objection also, in some instances, applied to large casks. The system of krausening and priming was not directly intended for the latter, unless these were specially made to stand high pressure. He was entirely in favour of conditioning in large bulk, and would give the preference to tanks, where the complete process could be carried out in the one vessel.

Mr. J. M. Lones remarked that he had been particularly interested in the figures of the gas percentages, but confessed to being somewhat surprised to see such a small quantity shown to be carried by the highly carbonated beer. He would have expected at least from 0·36 to 0·38 grammes per 100 c.c. With regard to the comparative merits of krausen or priming, he thought the latter system was the better one, as it was common to find beer, to which krausen had been added, possessing an after yeasty flavour, which was not an altogether desirable one. Could Mr. Van Laor give him the original and final gravities of the beer he had examined, as these factors would probably have some influence on the production of CO2 in bottle?

Mr. Van Laer asked if he understood Mr. Lones to mean that he considered the percentage of CO2 in the beers was low. If that was the case, he would point out that the quantities he had given were, by practical experience, proved to be quite sufficient for the average bottled beers of this country. Of course, there might be some exception to the rule, and this perhaps in certain particular districts. From the researches of Drs. Wahl and Henius, on the subject of percentages of carbonic acid in bottled beer, these experts had shown that if a beer contains less than 0·30 per cent, of carbonic acid in the bottle, or less than 0·25 per cent, in the glass, the taste of the beer would be flat. Therefore, from the figures he had given, one could see that the amount of carbonic acid produced with 10 per cent, of krausen, or 2 pints of priming to the barrel, and that contained in the extra carbonated beer was approaching the American standard quantity put forward by Drs.Wahl and Henius, which really applied to beers more gaseous than the majority of British bottled beers.

The President said that Mr. Van Laer when referring to the question of flavour remarked that beers were hopped down with 10 to 12 ounces per barrel of Bavarian hops. No doubt, a strong hop was useful in filtered beers as a certain loss of bitterness took place in the process possibly due to the chilling causing a greater precipitation of hop resins than took place in ordinary storing. With regard to the amount of carbon dioxide in beer, it had often been a question whether the difference between that which was forced into beer as when using a carbonating machine, and that produced in the beer by fermentation was that the latter was carbonic acid H2CO3 or a weak combination of the gas and alcohol. With reference to the CO2, the experiments quoted seemed to have been made in bottles. It was all very well to say a filtered beer should contain so much gas, but the difficulty was to fill bottles with such a saturated beer without great loss by fobbing. Sufficient gas might be obtained in a barrel or metal tank, provided the beer placed therein had sufficient fermentable matter in it to produce the same, and the temperature of the 8tore room was satisfactory, the question of the material of which the containing vessel was made was of no .consequence from a gas producing point of view, but unless care were taken during the transfer of beer from vessel in beer store to the vessel in cold store, loss of gas might take place which fermentation in cold store, being so slow, cannot replace. The question of the time during which a beer should be in cold store before filtering was still a problem, but there was no doubt that the longer a beer remains at the temperature of the cold store the less readily would it throw down a sediment when bottled. A beer of ordinary cellar temperature, instantaneously chilled and filtered, had a tendency to form a sediment in bottle sooner than a beer stored for several days at a low temperature and then filtered. As to the question raised by Mr. Wilson, the number of yeast cells varying in filtered beers of apparently equal brilliancy, he thought that might be coupled up, with not only the compactness of the filtering material, but also the state of the beer when passed to the filter, for it was well known that if the filtering surface were coated early with sediment it acted as a more efficient filter, so that when a fairly bright beer was passed to the filter without depositing much sediment on the pulp, the probability was that, although when filtered the beer might appear bright, more yeast cells might be in suspension than in a beer equally bright which had passed through a sediment-coated pulp. He was surprised to hear that it was advisable in some cases to fine beer before filtering, for if isinglass were used for the purpose there would be great danger of clogging the filters. He would like to know whether Mr. Van Laer had had any experience in use of filtered air for forcing beer into the filter press. If so, were there any objections to it?

Mr. Van Laer said that with regard to the mention made of 8 to 12 ounces of dry hops to the barrel, that quantity seemed certainly very high and especially with Bavarians. But that amount of hops was really only intended for beers which had to undergo the slow conditioning in casks as described in the natural process. The experience of some brewers who worked on this process was, that unless they doubled the usual quantity of dry hops, there was a tendency for the beer to lose some of its aroma by filtration. Bavarian hops were invariably used in preference to English. This was, perhaps, on account of their high preservative properties, and aroma which was well maintained during filtration. With regard to the amount of CO2 in beers and the losses sustained during the operations, he would say that in some cases the loss of CO2 was very heavy, especially if the manipulations were not carried out at temperatures at which the gas would remain in solution. When the required quantity of gas was produced, the beer should be chilled in the same vessel and the operations of nitration and bottling performed at a temperature of about 32° F. Moreover, back pressure bottling machines should be used for this purpose. As to the question of time required for conditioning, when using the prescribed quantity of krausen, the experience of brewers who were working on that system was, that sufficient gas was produced in about seven days, when the beer was kept at a temperature of 58° F. or thereabouts.

As to the question of colour after filtration, he had himself noticed sometimes an increase by filtration, and ongoing carefully into the matter he found that this was the case with certain pulps of inferior quality. These pulps which influenced the colour acted also on the flavour of the beer. This he attributed to the chemicals used in the manufacture and bleaching of the pulp. As to the question of using air for forcing beer from the vessels through the filter, it was undoubtedly a great economy to do so over the employment of CO2. But he would point out that the air should be pure and taken from a source where there was no danger of introducing infection, and if that could not be obtained it was always advisable to previously filter the air. In using air for forcing purposes, it was most essential that the latter should not get mixed with the beer. Compressed air was very largely used in a number of Continental breweries, and from the experience lie had had with it for a good many years, he had no hesitation in saying that he had never experienced any trouble with it.

The President said that they were very much indebted to Mr. Van Laer for his paper. It was a paper which had proved very interesting to the members, and he was pleased so many had taken part in the discussion. He had great pleasure in tendering their thanks to Mr. Van Laer.

Mr. Van Laer suitably acknowledged the compliment, and the meeting then terminated.