FAST AND SLOW FERMENTATION OF BREWER’S WORT BY STRAINS OF SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE

By S. R. Griffin (Brewing Industry Research Foundation, Nutfield, Redhill, Surrey)

Received 21st July, 1969

The major biochemical factor determining whether astrain of yeast will ferment wort rapidly is the activity of the yeast in fermenting maltose. However, maltase is always present in sufficient quantity and consequently maltose permease determines the rate of utilization of this sugar by the yeast. Similarly, the utilization of maltotriose is thought to be governed by the uptake system for this sugar.

Introduction and Discussion

Brewing yeasts in the National Collection of Yeast Cultures include strains which differ in their rate of fermentation of brewer’s wort.13 However, it is not known whether this difference is due to the rapidly fermenting strains having a high activity towards wort sugars, to larger amounts of yeast being present in the medium or to the pattern of utilization of carbohydrates being different, several sugars perhaps being used simultaneously by some strains but not by others.

sucrose from the wort. In addition, these yeasts fell into two groups if the amount of glucose present when In the present investigation five strains comprising three rapidly (Nos. 1018, 1073, 1037 N.C.Y.C.) and two slowly (Nos. 1025 and 1111 N.C.Y.C.) fermenting yeasts were grown in hopped wort. The pattern of fermentation of each strain as reflected by the reduction in specific gravity, growth of cells and other properties was followed. The patterns of reduction in specific gravity (Fig. 1) suggest that usually the more rapidly a strain ferments, the more completely it ferments wort. This is not in variably so, since one extremely slow yeast (No. 1025) finally reduced the specific gravity of the wort to 1·006 after approximately 200 hr. The second slowly fermenting strain (No. 1111) attenuated to 1·011, several degrees higher than the three rapidly fermenting strains.

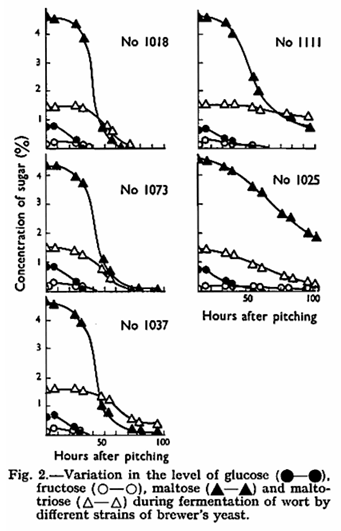

The patterns of removal of sugars from the wort during the course of fermentation by the five strains investigated are shown in Fig. 2. If the utilization of monosaccharides is considered these yeasts fall into two groups. The three rapidly fermenting strains removed all the glucose in the first 28 – 30 hr. of fermentation whereas the two slowly fermenting strains did not use all this sugar until after 50 – 60 hr. The same pattern, although not so clear cut, was apparent for fructose although there was, for all strains, an initial increase in the amount of fructose present which correlated with the disappearance of uptake of maltose began was considered. There was 0·7 – 0·76% glucose present when uptake of maltose began using rapidly fermenting yeast and 0·55 – 0·6% for a slowly fermenting strain; this is doubtless simply a reflection of the high activity of the rapidly fermenting yeasts.

Utilization of maltotriose was variable and not related to the speed of fermentation exhibited by any strain. For example, strain No. 1025, a very slow fermenter, used 85% of the maltotriose within the first 100 hr. of fermentation. It is interesting to note that while three strains (Nos. 1018, 1037, 1111) did not utilize maltotriose until all the glucose had gone, two (Nos. 1025 and 1073) started to use maltotriose about 15 hr. after pitching when there still remained 0·5% glucose in the medium. It would appear that sequential uptake of sugars9 by these two yeasts is considerably telescoped, especially in No. 1025 where the bulk of the maltotriose was utilized before half of the maltose had disappeared. This behaviour is contrary to the normal pattern in both Sacch. cerevisiae and Sacch. carlsbergensis although one strain of the latter (No. 396) also utilizes maltotriose more rapidly than maltose during fermentation of wort.8 It appears then that the rate of utilization of maltotriose by yeasts is only of secondary importance with respect to the speed of wort fermentation and also that it is not always the sole factor determining the degree of attenuation achieved by any strain. The amount of yeast in suspension during fermentation is shown in Fig. 3. Two of the yeasts chosen for study were atypical in that one (No. 1025) was extremely flocculent, only small amounts of yeast remained in suspension, and growth was poor giving after 100 hr. a total crop only one third of that obtained using the other four yeasts (35 – 45g. fresh weight). The other (No. 1037) fell out of suspension and the head collapsed very early on in the fermentation to leave a bright beer after about 70 hr. However, the latter strain fermented so vigorously from the sediment that large floes were periodically carried well into the medium. The fermentative capacity defined as the potential of each of the strains towards glucose and maltose was followed throughout the course of fermentation and is shown in Fig. 4. The pattern is different for each yeast and while there is a tendency for rapidly fermenting yeasts to possess higher activity, this is not always so. This is probably due to the speed of fermentation being a function of both the activity and the amount of yeast and thus it is not possible to predict the performance of a yeast strain solely from manometric measurements. This is due to the artificial conditions of manometry in which effects of concentration, composition, competition and inhibition present in a wort fermentation are deliberately eliminated. It is not surprising that only the most general conclusions as to fermentative behaviour can be drawn from fermentative capacity measurements.

Knowing the amount of yeast in suspension and the rate of change of sugar concentration at any given time, the activity of each strain towards the individual wort sugars when actually in the wort fermentation can be calculated. Since there had been no interference with the yeast in any way the entry of a sugar will be in equilibrium with the internal utilization and thus the rate of disappearance of that sugar provides a true measure of the metabolism of the yeast toward that sugar in wort under “natural” brewing conditions. As can be seen from Fig. 5, the yeast which fermented wort most slowly (No. 1025) had a low activity for maltose whereas its fermentative capacity (Fig. 4) towards that sugar was reasonably high. Similarly, although the fermentative capacity of No. 1073 was higher than that of No. 1018 (a faster fermenter) the second yeast had a higher activity in the wort. Each of the strains exhibited a distinct pattern of fermentation of maltose (Fig. 5) and the two strains which fermented wort slowly had lower activities than the rapidly fermenting ones.

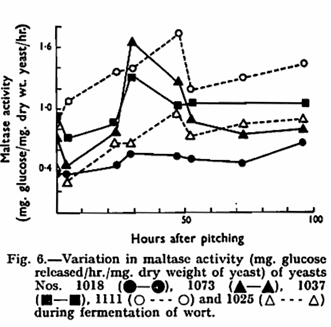

Since the rate of fermentation of maltose is the most important factor in determining the rate of wort fermentation, the maltase activity of each strain was estimated during the course of wort fermentation. It can be seen (Fig. 6) that this activity neither changed in relation to the pattern of utilization of wort sugar nor could it be related to the speed of wort fermentation of the different strains. Simple calculation shows that in all strains there was more than enough maltase present to deal with the observed rate of loss of maltose from the medium. The excess of this enzyme must be even greater when it is considered that the extraction technique used is known to be inefficient.8 It appears that maltose permease must be the factor controlling the rate of maltose utilization by the yeast. These conclusions are in agreement with earlier results.4,6,8 The activity pattern is broadly similar to that shown by Millin for another strain of yeast7 although the rise in activity during the final stages of fermentation was not observed earlier and the initial drop in maltase activity does not appear to be a general feature since in two of the strains (Nos. 1018 and 1111) it was not apparent. Maltotriose-splitting activity was present throughout fermentation in all the strains studied. Thus, it is likely that the fermentation of maltotriose like that of maltose is controlled by the uptake system rather than by any particular glucosidase.

Experimental

Materials. — Pure maltose and maltotriose were prepared from commercial starch syrups by chromatography on cellulose.5

All-malt hopped wort mashed at 150° F. and having specific gravity 1·040, pH 5·0, attenuation limit circa 1·006 was used.

Preparation of pitching yeast. — The yeasts, obtained from the National Collection of Yeast Cultures, were grown in hopped wort (400 ml., O.G. 1·040) for 3 days at 25° C. with shaking, harvested by centrifugation and pitched at a rate of 2·5 g./litre (500 mg./ litre dry weight).

Fermentations. — These were carried out using E.B.C. (2 litre) tall tube fermentors as described by Dixon.8 The yeast in suspension and the specific gravity of the medium were estimated at intervals. Total carbohydrate of worts or partially fermented beers was assessed by means of anthrone10 and individual sugars by means of gas-liquid chromatography.1 Descending paper chromatography was also carried out on these samples using the solvent system propanol, ethyl acetate, water (7:1:2) and detecting the separated sugars using silver nitrate.11 Samples of yeast were taken at intervals for estimation of fermentative capacity and enzyme activities.

Fermentative capacities. — Evolution of carbon dioxide at 25° C. under anaerobic conditions was observed by conventional manometric techniques.12 Yeast samples from wort fermentations were resuspended in 0·066-M KH2PO4 solution, pH4·6. Warburg flasks contained 2·5 ml. of the yeast suspension (approx. 2 mg. dry wt. of cells per ml. final concentration) in the main compartment and 0·5 ml. of carbohydrate solution (1% final concentration), which was added from the side arm after equilibration. Corrections were applied for endogenous fermentation by means of suitable controls.

Maltase activity. — This enzyme was extracted by means of ethyl acetate.6 The treated cells were then suspended in citrate phosphate buffer,3 pH 7·0. The reaction mixture consisted of treated cells in buffer (1 ml.) added to an equal volume of maltose (5 mg./ml.) and the assay was carried out as described previously.4 Glucose released was estimated by a glucose oxidase procedure.4 Enzyme activity was expressed as glucose released (mg.) per hr. per mg. dry wt. of yeast.

Maltotriose splitting activity. — This was estimated qualitatively using cells broken in buffer with a Mickle disintegrator as the enzymic extract.4 The reaction mixture consisted of equal volumes of disintegrated yeast cells in buffer and maltotriose (10 mg./ ml.). After incubation at 35° C. for 40 min. the reaction mixture was spotted on paper chromatograms which were then treated as described above.

Acknowledgement. — The author thanks Dr. A. H. Cook, F.R.S., for his help and encouragement during the course of this work.

References

1. Clapperton, J. F., & Holliday, A, G., this Journal. 1968, 164.

2. Dixon. I. J., this Journal. 1967, 488.

3. Gomori, G., Methods in Enzymology, 1954, 1, 138.

4. Griffin. S. R.. this Journal, 1969, 342.

5. G. Gross, D., & Albon, N., Analyst. 1963, 78. 191.

6. Harris, G., & Millin. D. J.. Biochem. J., 1963. 88. 80.

7. Millin, D. J., this Journal, 1963. 380.

8. Millin. D. J., & Springham. D. G., this Journal, 1966. 388.

9. Phillips. A. W., this Journal. 1955. 122.

10. Pinnegar, M. A., & Whitear. A. L.. this Journal, 1965.308.

11. Trevelyan, W. E., Procter, D. P., & Harrison, J. S., Nature, Lond., 1950, 166, 444.

12. Umbreit. W. W.. Burris, R. H.. & Stauffer. J. F., Manometric techniques and tissue

metabolism. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Co.. 1957.

13. Walkey. R. J., & Kirsop. B. H., this Journal. 1969. 393