The INFLUENCE of pH and of SELECTED CATIONS on the FERMENTATION of MALTOSE and MALTOTRIOSE

By K. Visuri and B. H. Kirsop (Brewing Industry Research Foundation, Nutfield, Redhill, Surrey)

Received 12th February, 1970

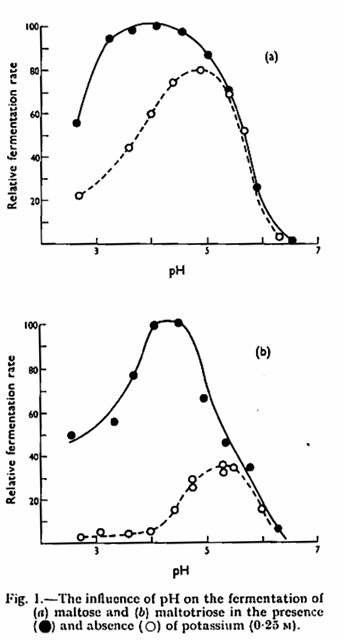

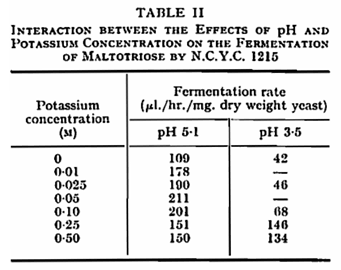

The fermentation of maltose and maltotriose in metal-free buffer solutions strongly depends on the pH value; the optimum pH is close to 5·0 and activity diminishes to zero above pH 7·2. Potassium stimulates utilization of these sugars at pH values of 5·0 and below, but in contrast to the situation with glucose, pH still influences fermentation markedly in the presence of potassium. Both pH and potassium influence sugar uptake rather than internal metabolism. Zinc, magnesium and ammonium ions stimulate utilization of both sugars by stimulating uptake mechanisms.

Introduction

Although the effect of pH and the presence of cations on the fermentation of glucose by Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been extensively studied13,15,10,18,19,1 comparatively little attention has been paid to their influence on the fermentation of maltose and maltotriose. In view of the importance of these two sugars in the fermentation of wort it seemed worthwhile to determine whether variation in pH and the presence of selected cations influenced their utilization by yeast cells grown in wort.

Results

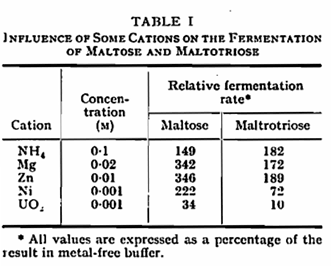

In the metal-free buffers used, the optimum pH for the fermentation of both maltose and maltotriose by N.C.Y.C. 1215 lay close to 5·0 (Fig. 1). Activity declined rapidly at pH values above the optimum and was absent above pH 7·2. At low pH, activity persisted to some extent even at pH 2·5 and the fermentation of maltose was less affected by low pH than that of maltotriose. The presence of potassium (Fig. 1) or sodium reduced but did not eliminate the inhibition of fermentation at pH values below the optimum. In this and certain other experiments the presence of potassium displaced the pH optimum to a lower value. A number of cations other than potassium have been shown to influence the fermentation of glucose by yeast,1,19 either by stimulation or by causing partial or complete inhibition. When a number of cations were tested for their effect on fermentation by N.C.Y.C. 1215 at pH 5-0, NH4+, Mg++ and Zn++ were found to give substantial stimulation of both maltose and maltotriose fermentation (Table I), Ni++ stimulated maltose fermentation, while UO2++ greatly reduced the utilization of both sugars. With regard to the fermentation of maltotriose, it was found that at pH 3·5 a higher concentration of potassium was required to give maximum stimulation than at 5·1 (Table II).

In agreement with published work,6 NH4, K+ and Mg++ were found to be without effect on the activity of maltase.

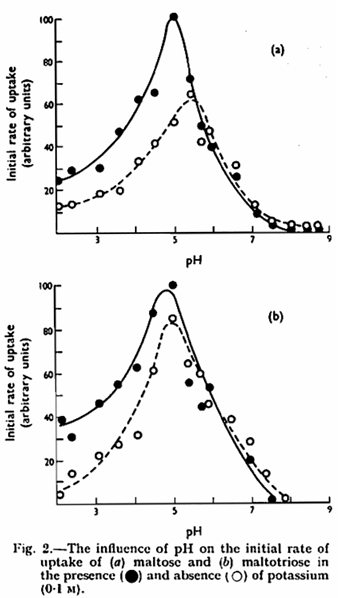

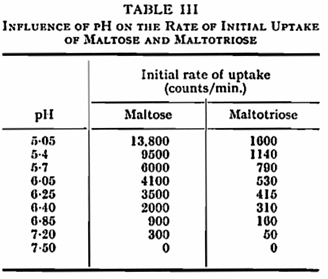

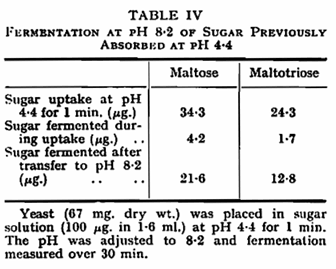

Maltose and maltotriose labelled with C14 were used to study the effect of pH and potassium on the rate of uptake of sugars, as measured by the absorption in the first minute after mixing the yeast and sugar. During this period the uptake of sugar followed a linear course. Uptake of the two sugars was influenced by pH in the same manner as fermentation (Fig. 2) and a detailed study of uptake at the higher pH values revealed that this was absent above pH 7·2 (Table III). That pH primarily influenced uptake of the sugars rather than their further utilization was confirmed by allowing yeast to absorb sugar at pH 4·4 for one minute and then altering the pH to 8·2. At the latter pH metabolism of the sugar previously absorbed at pH 4·4 continued (Table IV).

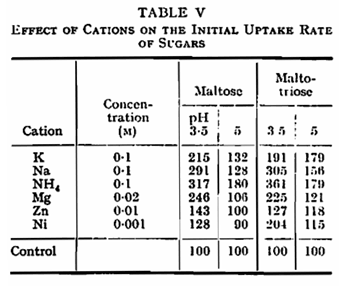

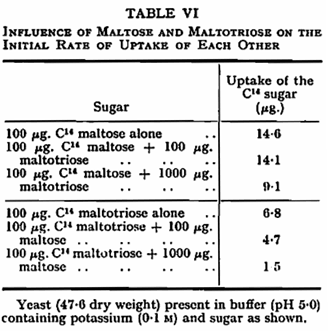

Potassium was found to increase the rate of uptake of maltose and maltotriose at pH 5·0 and below but not at higher values (Fig. 2, Table V). This result again parallels that of potassium on fermentation showing that potassium influences sugar uptake rather than internal metabolism.12 Sodium and ammonium ions similarly stimulated the rate of initial uptake of both maltose and maltotriose at pH 3·5 and 5·0. Magnesium, zinc and nickel activated uptake substantially only at pH 3·5 (Table V). The uptake of maltose was slightly reduced by the presence of an equal concentration of maltotriose and to a greater extent by a tenfold concentration of the trisaccharide; similarly, maltose inhibited maltotriose up take (Table VI).

Discussion

The anaerobic utilization of maltose and maltotriose is clearly influenced by pH to a greater degree than that of glucose. In particular, the biphasic curve obtained with glucose13 is not found with the two sugars studied here. The second component of uptake, effective at alkaline pH in the case of glucose and galactose,21 is absent in the system for uptake of maltose and maltotriose. The absence of uptake of maltose and maltotriose at pH 8·5 contrasts with earlier findings7,8 that these sugars were absorbed but not metabolized at this pH. In the present circumstances and conditions, and when a different strain of yeast is used, metabolism of previously absorbed sugars continues at the higher pH, although its uptake is prevented. In the strain used in this work, the uptake system which is active at acid pH is clearly similar in the case of all three sugars, since the pH optimum is similar, and the uptake system is stimulated by potassium in all cases. The degree of stimulation of maltose and maltotriose utilization is less than that reported for glucose13 where potassium removed pH dependence over the range 2·0 – 5·0. The difference persists, at least in the case of maltotriose, when the concentration of potassium necessary to give maximum stimulation is used (Table II).

The stimulating effect of zinc, and for maltose fermentation, of nickel, contrast with earlier reports of the inhibiting action of these metals on glucose fermentation. Whether the effect of zinc, for example, reflects a deficiency of this element within the cells or whether, with regard to maltose and maltotriose, zinc stimulates sugar uptake remains to be studied.

With regard to nickel the stimulation of the fermentation of maltose was eventually followed by a reduction in rate to values lower than those of control samples. It may be that the early stimulation represents the activating effect of nickel on the uptake process while the later deterioration reflects inhibition due to interference with internal metabolism.3,4 The inhibition of fermentation which immediately follows the addition of uranium reflects the known reaction of this metal with polyphosphate components of sugar transport systems.13,18

The stimulatory cations have, in general, a remarkably similar effect on maltose and maltotriose uptake. The demonstration that each of these sugars competitively inhibits the uptake of the other shows that both sugars must share a common step in the uptake mechanism; this is presumably the carrier step in the transport mechanisms proposed elsewhere.19,2,15,17

Experimental

One strain of yeast (N.C.Y.C. 1215) was used throughout. Cultures were obtained from the National Collection of Yeast Cultures and cells were grown in hopped wort for three days at 25° C. before use. When radioactive sugars were used, the wort was filtered before inoculation, for solid, brown coloured, particles in the wort led subsequently to counting difficulties.

Fermenting activities were measured by standard Warburg procedures.16 The buffers employed were (a)14 tartaric plus succinic acids (0·02 M) adjusted in pH with triethyl amine (pH 2·0 – 5·5), (b)14 Tris-(hydroxy methyl) amino methane (0·04 M) and succinic acid (0·064 m) adjusted with triethylamine (pH 5·5 – 9·5), and (c) tris (0·15 M) and citric acid mixtures (pH 2·2 – 9·5).

Cations were tested as sulphate (Mg++, Ni++, Zn++), as chlorides (NH4+, Zn++, Na+ and K+) or as acetate (UO2++)

Maltotriose was obtained by the hydrolysis of starch and purified by chromatography on cellulose columns. Maltose was purchased. CM-labelled maltose and maltotriose were purified by paper chromatography from material supplied7-8 by the Radiochemical Centre, Amersham.

To measure the rate of sugar uptake, yeast suspension (0·5 ml., 20-50% yeast by volume) was added to buffered labelled sugar solution (0·5 ml., 0·1 mg. sugar); after a suitable time, usually 1 min. at 20° C, the uptake of radio-active sugar was terminated by the addition of ice-cold “stop” solution (8 ml.) containing non-radioactive sugar (1%) buffered to pH 8·7 with tris-citrate (0·06 M). The yeast was collected by centrifuging (1 min.) washed once with “stop” solution and then placed in boiling water (2 min.). The yeast was finally transferred into the counting vial with water (3 x 0·2 ml.) and mixed with scintillator11 (5 ml.). Counting was carried out at room temperature using an EKCO N 664 B scintillation counter at room temperature. This procedure was adopted because attempts to solubilize yeast cells to give clear non-quenching solutions were unsuccessful; it also proved impossible to extract all the C14 from the cells.

Maltase activity was measured by a method described by Griffin.5

Acknowledgement. —The authors wish to acknowledge the continued interest of Dr. A. H. Cook, F.R.S., in this work.

References

- Booii, H. L., Rec. Trav. Bot. Neerlandais, 1940. 37, 43.

- Feiderkauf, F. A., & Booij. H. L., Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1968. 150, 214.

- Fuhrmann, G. F., & Rothstein. A., Symp. Soc. exp. Biol., 1954. 8, 155.

- Fuhrmann, G. F., & Rothstcin, A., Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1968, 163. 331.

- Griffin. S. R., this Journal. 1969. 342.

- Halvorson, H.. & Ellias. I… Biochim. biophys. Acta. 1958, 30. 28.

- Harris, G., & Thompson. C. C. this Journal, I960. 293.

- Harris, G.. & Thompson. C. C, Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1961. 52. 176.

- McIlvaine. T. C. J. biol. Chem., 1921. 49. 183.

- Passow. H.. & Rothstein, A.. J. gen. Physiol., 1960.43. 621.

- Patterson, M. S., & Greene. R. C. Analvl. Chem., 1965, 37, 854.

- Pena, A.. Ciuco, G., Gomez Puyou, A., & Tucna, M.. Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1969. 180. 1.

- Rothstein, A., Active Transport and Secretion, Symposium, Soc. Exp. Bio!., VIII. 1954, 105.

- Rothstein, A., & Dennis, C. Arch. Biochem. Diophys., 1953, 44. 18.

- Rothstein. A., & Van Steveninck. J., Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.. I966, 137. 606.

- Umbrcit, W. W.. Burris. R. H.. & Stauffer. J. F.. Manomelric Techniques and Tissue Metabolism. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Co., 1951.

- Van Steveninck. J., Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1968, 163. 380.

- Van Steveninck, J., & Booij, H. L., /. gen. Physiol.. 1964. 48. 43.

- Van Steveninck. J.. & Rothslcin. A., /. gen. Physiol.. 1965. 49, 235.

- Van Steveninck. J.. Biochim. biophys. Acta. 1966. 126. 1S4.

- Van Steveninck, J., & Dawson, E. C, Biochim. biophys. Acta, 1968. 150, 47