MEETING OF THE LONDON SECTION HELD AT THE CHARING CROSS HOTEL STRAND, ON MONDAY, DECEMBER 12th, 1927.

Mr. James Stewart, in the Chair.

The following Paper was read and discussed: —

FININGS.

By H. W. Harman, J. H. Oliver, and Phyllis Woodhouse.

Before describing some of the properties of finings it is desirable to consider briefly the different stages of brewing, and the character of materials, in so far as they are related.

Water and Water Treatment. — There are two points which may be referred to in connection with water and its treatment (1) alkalinity, (2) content of calcium sulphate.

Alkalinity has an important influence upon the diastatic activity of the malt used, and upon the amount of nitrogen dis solved in the wort during mashing. Generally, the less alkalinity as a result of acid treatment or by boiling, the more favourable the conditions are for a beer to fine satisfactorily.

The amount of nitrogen in the wort might directly influence the behaviour of finings (and, as we shall show presently, the question of nitrogen is of some interest in connection with finings), and indirectly act beneficially in providing increased soluble nitro gen with a resulting greater activity of the yeast in fermentation.

The action of calcium sulphate, either naturally present in the water or added, comes under much the same category as it is largely a nitrogen question. As is well known, the calcium sulphate interacts with phosphates, bringing about a change, at present not well defined, in the nitrogenous character of the wort. In practice we have met with one or two cases where large quantities of calcium sulphate have been used in the mashing liquor, with the result that the beer has shown decided stubborn ness in fining. As a general rule, for quick trade beers, which are required to fine rapidly and brilliantly, calcium sulphate in large amount may be considered undesirable, or at least unnecessary.

Grist. — We still await reliable information as to how far the nitrogen of a malt from a foreign barley differs, if it does differ appreciably, from that nitrogen of a malt from an English barley. But it is safe to say, and experience amply bears out the contention, that under-curing or want of even-curing are accompanied by bad results both in fining and in brewing. Another objection to what may be described as over-cured, or high-dried malt, is that it favours that condition of bad fining known as “thick and clear drawings.” Such malt provides a wort of dextrinous character, encourages a tendency to feeble conditioning of the beer at racking, and lends itself to infection from the cask, usually the immediate cause of this unpleasant condition of the beer.

Sugar and flaked maize may be considered as diluents of the total nitrogen of the grist used, and it is a well-known and common practice, when it is required to accelerate brilliant fining of a beer, to increase the proportion of sugar, and to some extent also of the flaked maize, and there is no doubt that in some districts, where very early brilliancy is required, it is safer to use a relatively high percentage of these two materials.

A word may be said as to slack malt which, correctly or otherwise, has been held responsible for difficulties in fining. There is certainly some enzymic change affecting the protein as a malt gets slack, and although re-drying has advantages in better grinding and to some extent better flavour, it probably has little value in re-adjusting the character of the protein.

Mashing Heats. — The practical effect of a high mash heat is a more dextrinous type of wort with a tendency to slowing down the fining. A low heat has the reverse effect, which makes it more commonly adopted for quick trade beers. A high heat, which presumably will allow a certain period of maturing in cask, is more usually adopted for beers of bitter or pale ale type, since the essential condition of rapid fining of a new beer is not perhaps so important with a beer of this kind.

The explanation may well be associated with the protective influence of dextrin colloids on the nitrogenous colloids in a beer, and we shall be referring to this later in dealing with the protective power of isinglass. Generally speaking, the newer a beer with regard to racking, the quicker the response to fining, but the earlier the tendency to revert to a hazy condition than would be the case with slower fining.

It should perhaps be remembered that the use in any quantity of adjuncts such as flaked maize is more suitable for methods of brewing in which a low mash heat is required; as a higher mash heat, producing a dextrinous wort, may exert a more protective action on the beer proteins, and so tend to make fining slow.

Copper Boiling. — We think that the importance of good copper boiling does not always receive the consideration it deserves. We have known cases where an imperfect boil has been responsible, not so much perhaps for a bad initial fining of a new beer, as for a tendency for such a bright fined beer to show haze at an early stage. It is possible only to determine the efficient boiling by the character of the break, and more information as to the relative value of a long boiling at atmospheric pressure and short boiling under pressure is needed. If there is not a good break either as a result of the materials used, the mashing method; or character of the boiling, the protein bodies may be in an unsuitable condition to take finings at the end of fermentation.

Yeast and Fermentation. — Both pitching rate and character of the fermentation are, no doubt, of considerable importance in the fining of a beer. Too low a pitching rate may induce an excessive reproduction of small cells, and give rise to “fretty” condition of the beer at the end of fermentation, making fining difficult. Although a beer may fine when in an active state of fermentation due to primary yeast, it certainly will not do so, as everybody knows, when fer mentation is going on, either with a weak primary yeast after racking, or one of secondary type.

A weak reproduction, which so often happens when a yeast of an attenuative type is transferred from one brewery to another, is intensified, and under the new conditions the yeast frequently declines to skim completely and produces a “fretty” type of beer at racking, which will not fine for a considerable time. We have occasion ally seen this happen, although after a time the yeast appears to recover its more normal conditions.

Another point is in the unsatisfactory cleansing of the yeast from the beer. This may bring about much the same results as just mentioned, and many brewers insist upon a healthy cleansing of the beer, even if it entails, as it sometimes does, a higher final attenuation.

Hop Back Filtration. — The condition and quantity of resin in the finished beer undoubtedly has an important bearing on fining, and, as resins are probably present, partly as salts the colloidal solution produced is of the same electric charge as the finings and cannot separate by mutual precipitation.

Cold Store Hops. — Objections have been made to the use of cold store hops, or the use of too new a hop, as liable to interfere with fining, but we think that this depends largely upon the quality and condition of the hop; such as ripeness, rather than anything else.

Metals. — Mention should be made of the effect of metals on beers, more particularly iron, which probably forms a compound with protein. Any iron in excess of 0″25 grain per gallon is liable to affect flavour, and with increasing amount the brilliancy of a bottled beer.

We propose now to show the results of some experience on the behaviour of finings as they are normally used in the brewery. As everyone knows, finings are prepared from isinglass, a substance of a colloidal nature.

A colloid may be precipitated (a) by the addition of compounds with complex ions; (b) by the addition of neutral salts; (c) by a change in the reaction of the liquid; (d) by colloids of an opposite electric charge, and in brewing we find that the separation of the protein in beer takes place by all of these four methods: —

(a) The first occurs in the copper, where the positively charged proteins are precipitated by various complex ions of which the best known is tannic acid.

(b) The addition of neutral salts serves to explain the way in which an excess of calcium sulphate will interfere with’ finings. Salts of metals of bi-valent ions, such as calcium, have a specific action against negatively charged colloids, and it is reason able to assume that if there is a large amount of calcium sulphate present it will precipitate negative protein, and so lessen, as will be seen later, the quantity which is available for cloud formation during fining. Conversely salts of mono-valent ions, like sodium chloride, should assist in precipitating any positively charged protein, a process which a fining is incapable of carrying out.

(c) This takes place to a considerable extent during the change in pH from wort to beer, when there is a continual precipitation of protein matter throughout fermentation.

(d) The precipitation by colloids of opposite charge is more intimately connected with the process of fining proper.

It must be appreciated that colloidal solutions exist as particles bearing an electric charge, and the stability of the solution depends upon these charges. Under the circumstances the charge on a colloidal solution may be neutralised by the ions in the surrounding liquid, and for a given colloid there are definite points at which this takes place. If the pH of the solution at which this occurs be known it will be found to be quite constant for the same colloid; this point is known as the iso electric point. Certain colloids show one or more iso-electric points with some degree of sharpness, and in the case of fining it is certain that the solution possesses at least one fairly sharply. To make this clearer we can show two solutions to which finings, in equal amounts, were added a few hours previously. The first is of pH 4·9 and it will be observed that the fining has separated to a very considerable extent. The second is at pH 4·0, and very little separation has occurred. By repeating these experiments in greater detail, it can be shown that the iso-electric point of finings is about pH 5·0.

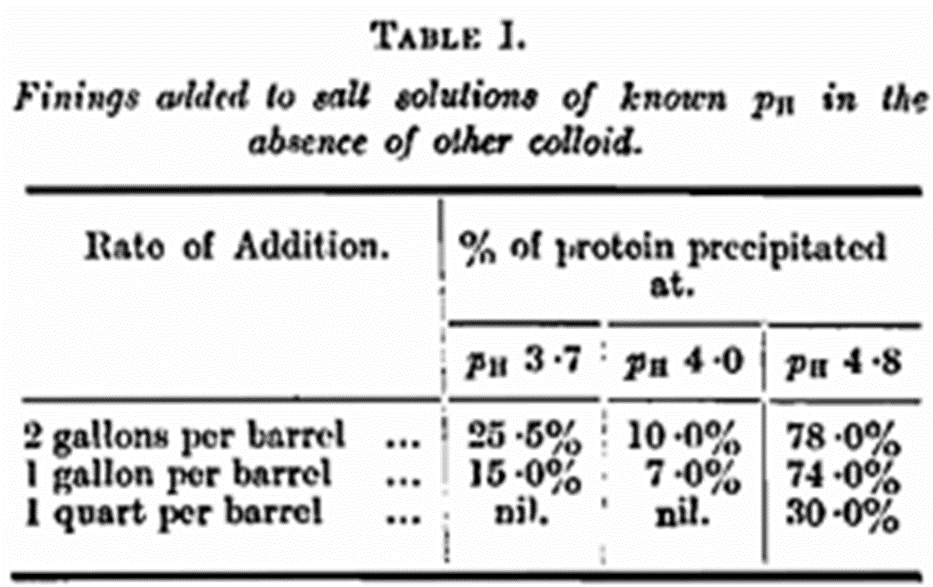

Some quantitative determinations were made using finings and buffer solutions only, and the results are given in Table I. The percentage precipitated naturally increases with the rate of addition, but the most important points to be noted are that (1) there is nearly 80 per cent, precipitated at pH 4·8, as compared with 10 per cent, at pa 4·0, and (2) at the rate of 1 quart per barrel the fining stays in solution completely at about the normal pH of a beer.

This last figure was confirmed by estimating the nitrogen in the clear solution. This fining contained 40 mg. per cc. and at the rate added, the whole solution theoretically contained 1·96 mg. nitrogen. It was found to contain at pH 3·7 — 2·1 mg. at pH 3·8 — 21 mg. and using another fining containing ·89 mg. per 1 cc. at the same rate 4cc. + 500, the solution contained 3·50 mg. nitrogen. It was found to contain at pH 3·7, 3·58 mg. at pH, 3·8, 3·50 mg, at pH 4·0, 3·30 mg.

We know that a beer will fine readily under ordinary conditions, and that normally it may have a pH value of from 3·8 to 4·2, so that we might expect finings had been chosen in practice because they give a colloidal solution with an iso-electric, or precipitation point, round about pH 4·4. This, however, is not the case, and with the usual addition of about one quart of finings per barrel of beer the finings are sufficiently soluble to resist precipitation. As a matter of fact, the optimum pH of a solution of good finings regarded iso-electrically is about 4·9, which suggests that the wort should be fined before fermentation. But, there are other factors operating which justify the procedure of experience.

If fining activity were determined only by precipitation, as a result of this neutralising effect of the opposite electrical charges, then the action on the beer particles would be only mechanical, and the completeness of separation would depend on the separation of the network of coagulated finings as they fall through the beer. But other electric particles have to be considered and beer from this point of view is simply a colloidal solution of protein, resins, etc. Just as electrical charges are neutralised by the ions causing precipitation so the presence of other colloidal particles of opposite charge will result in precipitation, and it is the combined effect of these conditions that produces the optimum fining of a beer.

Fining at Varying pH. — Now as beers will vary considerably in their pH value in different breweries, it was found necessary to examine different finings at varying hydrogen ion concentration.

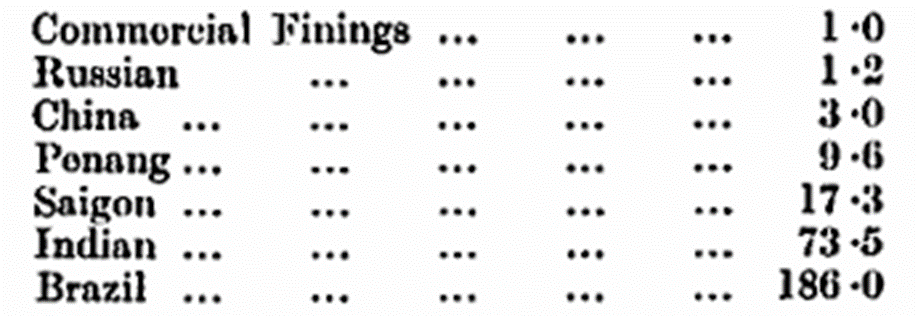

Instead of using a solution of salts for these experiments we introduced a certain amount of colloid by taking the unfined beer and buffering it to the desired figure. As aresult of these experiments it was found that finings from different sources of isinglass, which had been cut under the same con ditions, when used on the same beer, showed differences in the way they fined.

There are certain interfering factors. The amount of amorphous matter present in a beer is necessarily variable over three or four months, and isinglass may itself vary appreciably, but the general conclusions wo came to agreed quite well with practice. It may be said that Pcnang isinglass produces a fining having the widest range, so that it should work more or less satisfactorily with any class of beer. Saigon and Indian are alike in being suitable for more alkaline types of beer, as usually brewed from hard waters, whilst Russian was also found satisfactory for the most alkaline of this type of beer. We found that ” Brazil ” was of little value except for beers from acid treated water, or calcium carbonate water, which has been thoroughly boiled. China leaf in general was a good substitute for “Brazil.” In our experiments these different forms of isinglass were cut by using a mixture of tartaric and sulphurous acid, and the finings were sieved, etc., in the usual way.

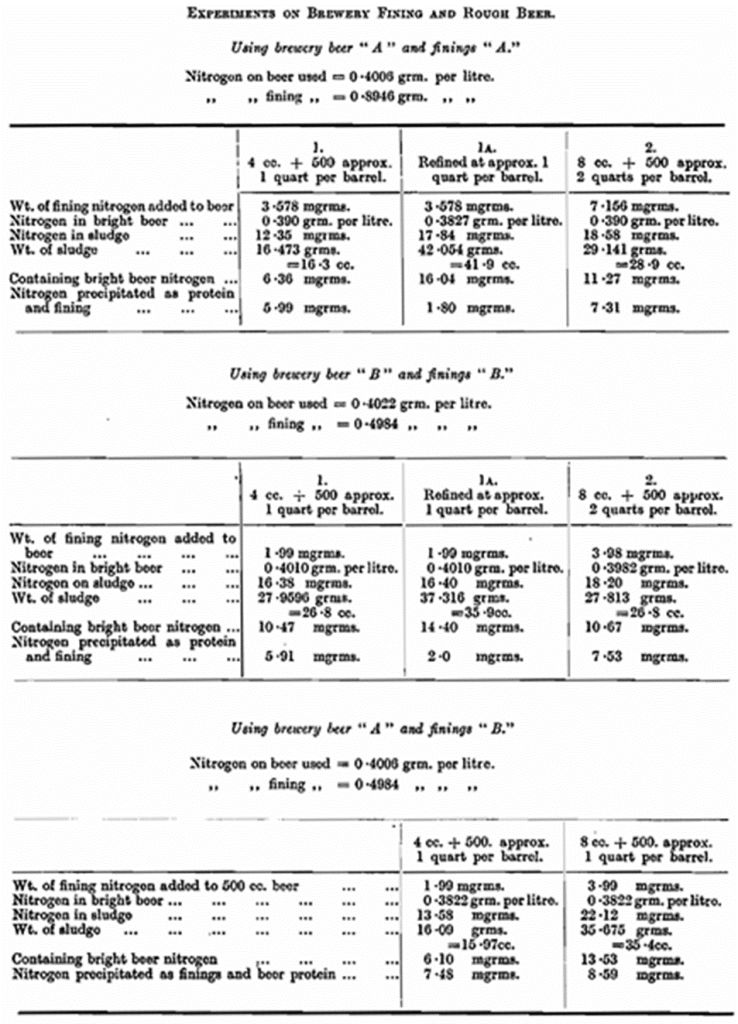

Effect of Nitrogen. — Some experiments were made on a quantitative basis using brewery finings and mild ale. Since the nitrogen content of finings is of the same order as that of beer, and as the amount added is, of course, very small, the actual change in the total nitrogen content of a beer is almost as small as to be within the region of experimental error. The only practicable method is to fine a considerable quantity of a beer in a piece of apparatus similar to a large burette, to run the sludge off in as small a volume as possible, and to determine the nitrogen in this sludge, making an allowance for the nitrogenous matter in the bright beer. This amount separated will be found to be considerably more than the finings added, and in the table are given some results of these experiments.

By increasing the rate of fining from one quart tot wo quarts per barrel, it is interesting to note that the separation of nitrogenous matter increases only very slightly. In a similar way in the second column is to be seen the result of re-fining, or, rather, adding a further quantity of finings to a beer that has been already fined.

If these figures are compared with these obtained with finings and buffer solutions of the same pa as the beers used, it will be seen that there the separation is practically negligible, and it must be assumed that in the present experiment the greater part of the separation took place owing to the presence of charged particles, which combined with the finings present.

The general result of these experiments made it obvious that when a beer is fined at a high rate, a certain amount of finings are left in solution, and even at lower rates some amount probably remains, and confirmation of this was obtained by further experiments.

Protective Influence. — One of the most interesting properties of a colloid is that it is capable of exerting what is known as a protective influence on another. Thus, under certain conditions, when separation or fining would normally occur, the presence of this protective colloid will prevent any precipitation. A considerable amount of work has been carried out on this point by various workers, and it is common knowledge that isinglass comes second in order in the Table of the most protective colloids, and is only exceeded in this respect by gelatine.

A simple experiment with a colloidal solution of gold will make this clear. This can be prepared in the form of a deep crimson solution, the less stable form, so that when an electrolyte is added the colour will change to a deep purple, whilst with excess of an electrolyte the colloid is completely precipitated. (1) If beer is added to a gold solution, the colour of the latter changes to blue, and (2) if smaller quantities of the same beer are fined, and added to colloidal gold there is no change, which exemplifies this protective power of finings. Thus, isinglass finings may, under certain conditions, not only fail to precipitate protein, but even stabilise a haze already present.

It can be assumed, therefore, that an amount of protein from the finings remains in the beer when it is fined, which may be as much as 50 per cent, of the finings added. As a result, the separation of the coarser particles during the process of fining is also accompanied by the stabilisation of the colloidal solution that still remains behind. Satisfactory fining in such a case would seem to be a result of a nice balance between these two factors, and as increasing the amount of finings results only in a larger amount remaining in the solution, the rate of fining seriously affects the protective power. Different samples of prepared finings vary appreciably in their protective power, the most protective we have met being about twice as active as the least. It is not very clear how this effect develops during cutting, and we tried to obtain some idea, by its measurement at different stages. (See Table.)

There is some difficulty in sampling isinglass that has been under the action of the acid for a few weeks only, one that we could not completely overcome, as is shown by the varying nitrogen content. It appears, however, that protective power, which is no doubt connected with certain of the proteins constituting isinglass, develops fairly quickly during the earlier stages of cutting. It is an interesting fact that this protective power of finings is entirely absent in finings which have been overcut. The analytical magnitude of this can be gauged by the fact that 1 cc. of isinglass, prepared by diluting 1 cc. to 500 ccs. will exert a protective action, whereas concentrated over-cut finings will not exhibit this property to any extent.

We should now like to discuss a few factors which adversely affect the finings of a beer, and one of the first to be considered is wild or secondary yeast.

Wild Yeast. — These organisms, of course, ought not to be present in any well conducted modern brewery, but, if not found inside the brewery, they may still appear in the cask plant.

In our experience there has been a very marked decrease in the appearance of wild yeast of Ellipsoideus type during the last few years, a yeast which at one time was very virile, and which has been associated with well-known yeast of stench type, and other smaller forms. These forms of active wild yeast seem to have decreased, but have been replaced by a commonly found type of yeast which for want of a better word, are known as Mycoderma type. These latter do not interfere with fining to the same extent as the former, but there is no doubt that they exert a direct influence on fining, so that very often accessory finings, or in some cases finings of greater concentration, must be added to the beer to make sure of good fining. There is ample opportunity for these secondary forms of yeast to infect a beer, and a fruitful source is often found in the topping up with bright beer, which may appear satisfactory enough to the eye, but is full of secondary yeast, and the danger of using any other than beer set aside from the same brewing for this purpose, is not always appreciated. This yeast is still plentifully found in the “back drink” of a stone square system of fermentation, and wooden fermenting vessels, however sound they may appear to be, are rarely free from it, and sooner or later it may accumulate to a serious extent.

Primary Yeast. — We have already alluded to the fact that the wort will fine perfectly and very quickly, and will continue to do so, throughout fermentation, until the stage is reached when the amount of yeast per volume becomes excessive, whilst even at this stage it is possible to obtain a bright layer of liquid by adding excessive amounts of finings.

Generally speaking, however, primary yeast will separate much more readily than secondary, the interference with fining of the latter being due to its peculiarly even distribution throughout the beer in which it is present.

Hop Resin. — Another factor, which we have mentioned, as affecting finings, is the presence of hop resin. An un-hopped wort will fine readily and brilliantly, whereas if hopped with increasing rates per barrel it becomes less and less satisfactory in proportion to the increased hop rate. To some extent this increased hop rate may be assisted by bad filtration in the hop back or by excessive sparging or sparging at too high a temperature.

Agitation. — In our experiments samples of various beers were fined down and subjected to differing degrees of agitation. The general conclusion was that beers fined to the same extent whether they had been shaken vigorously or gently, but if the finings were allowed to mix quietly separation might occur, but not nearly so completely or so thoroughly as with agitation. The reason is that the shaking assists inbreaking down the stability of the potentially unstable colloidal solution which is in agreement with the experience of several observers who have found that vigorous shaking is necessary to start separation from a colloidal solution. In our own experiments with gold solutions, varying the degree of agitation seriously affected the rate of separation or change of colour produced.

Carbon Dioxide. — The action of gas is of some importance in the fining of beer, and experiments were carried out with a series of flat beers in which small amounts of CO2 were introduced, giving top pressures between, 5 and 10 lb. per sq. in. On comparing the rates at which those beers fine, it was found that the gas accelerated the fining action in every case, with no interference or lessened brilliancy of the final beer. It is difficult to account for this, but it is possible that the nodules of gas were liberated when the finings were introduced in much the same way as the small amount of gas that escapes when finings are added to beer in cask – these small nodules of gas providing nuclei, which assist in the separation of the finings.

Temperature. — This is important and, generally speaking, the higher the temperature up to a point about 80° F., the more rapidly finings tend to separate, but if fining is carried out at this high temperature the brilliancy of the final beer tends to suffer. Fining may be carried out satisfactorily at low temperatures, provided that the finings and beer are not mixed and subsequently chilled. The probably reasons underlying these changes are that with a rise in temperature, certain colloidal matter is held in solution more tenaciously – the finings separate and during mechanical separation this portion of the protein is held back and subsequently settles out upon cooling. In the case of fined beer, a rise of temperature causes the finings to rise in the beer, and if the temperature is increased considerably, up to about 75o F., the finings will rise completely to the top and in re-settling do not always leave a bright beer, and here again mechanically-held protein is probably the cause of the trouble. Any variations of temperature after the finings have been added is inadvisable, an exception being when there is to be subsequent clarification by filtration.

Analysis. — Among the several attempts to obtain analytical standards for the purpose of comparing cut isinglass the best-known test is that of determining the viscosity of the finings. We believe it is generally appreciated that whilst it is useful for a brewery working on one type of isinglass to adjust the finings to a standard of viscosity, the test is of little use when comparing different sources of isinglass cut in different ways. Throughout our experiments of cutting isinglass of different sources we determined the viscosity after they had been cut for the same length of time, and the variations were considerable.

The order of the viscosities is as follows: —

Diluted to the same viscosity the fining power of the more viscous finings become very small and there was no comparison between finings from such isinglass when adjusted to the same viscosity.

As finings are always acid, it might be presumed that their addition would have a distinct effect upon the reaction of the beer, and some experiments were made adding finings at different rates per barrel. The results showed a small but distinct increase in pH, so that sound finings should tend to assist the stability of the beer.

Abnormal Precipitations. — It has been observed that finings will separate in a “sandy,” rather than in a normal flocculent condition. This effect can be produced in several ways, and may be induced to a small degree by very vigorous shaking of the finings in the beer. In the ordinary way the examination of brewery finings that have separated in a sandy condition reveals an unusually large amount of yeast as distinct from the more common masses of amorphous and resin matters. In experiments using finings in conjunction with kieselguhr, it was found that a fining that normally separated in a flocculent condition

became distinctly sandy. In a similar manner the addition of yeast before fining induces sandiness, so much so that the conclusion drawn from the series of experiments was that the more suspended solids present up to a point the quicker the resulting break, but the greater the tendency to a “sandy” precipitate.

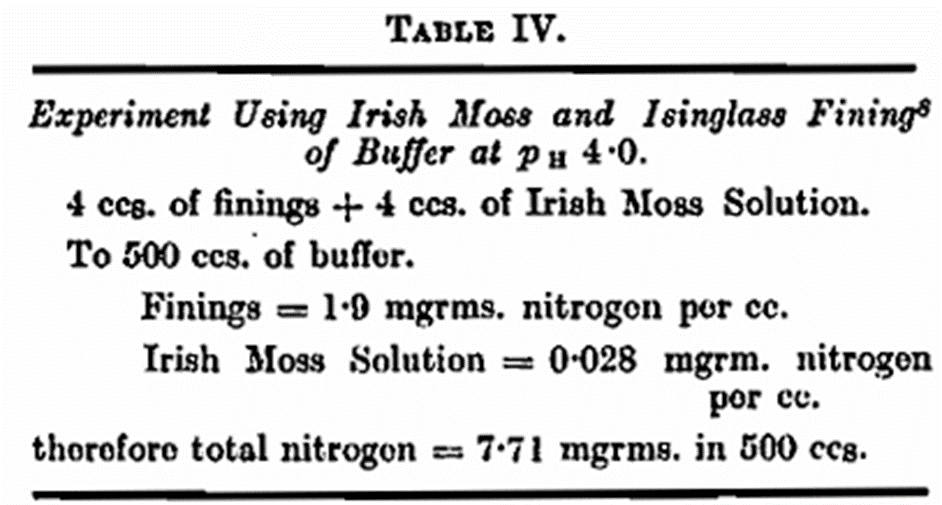

Auxiliary Finings.— From time to time many brewers make use of what are known as “auxiliary finings,” and a few remarks may be made concerning them. An auxiliary fining such as an Irish Moss preparation differs from ordinary isinglass in that electrically it is of opposite charge, with the result that if one mixes an Irish Moss solution and isinglass, neutralisation of charge takes place and precipitation occurs. It is sometimes found that the use of such adjuncts will improve fining, and even render this possible when ordinary finings are ineffective — even in cases showing an appreciable amount of secondary yeast infection. In such a case the beer contained a definite amount of protein of opposite charge to the isinglass, resulting in a limited amount of cloud being thrown out from the beer, but so much secondary yeast was interspersed throughout the liquid that this cloud was incapable of removing it all. Upon the addition of an Irish Moss solution, or a similar preparation, an increased amount of isinglass protein was thrown down, resulting in a cloud twice the size, which was able to separate all the secondary yeast. At the same time the removal of the precipitated protein no doubt had some effect in partially destroying the protective action existing in the remaining colloids. The suggestion that increased fining rate would produce greater precipitation is not borne out, since an increased fining rate does not involve an appreciably greater precipitation, because the amount of finings that can separate is limited by the amount of suitably charged protein in the beer.

We have stated quantitatively the effect of Irish Moss on isinglass as is set out in the accompanying table.

After mixing, precipitation occurred, and the sludge was removed and found to contain 0·9 mg. of nitrogen.

An addition of about 11 parts of Irish Moss nitrogen to about 760 parts of isinglass nitrogen has caused the separation of about 90 parts of Irish Moss and isinglass nitrogen.

In connection with auxiliary fining agents, mention should be made of the deliberate introduction of solids, such as finely divided kieselguhr, chalk, etc., substances which were certainly used to a great extent at one time to assist fining. The use of kieselguhr, particularly washed Kieselguhr, may be scientifically sound, although it acts better in assisting clarification of wort than in clarifying a beer, and, in the analytical examination of malt powdered kieselguhr is used on the filter to assist the brightening of the wort for the purpose of reading colour. The process undoubtedly involves separation by neutralisation of electrical charges since other powdered materials, such as pumice, are not nearly so efficient, or as efficient, as they should be, if the clarification was purely mechanical. In the case of fining beer the use of washed kieselguhr acts partly in an electrical manner and partly in weighting the cloud and speeding its settlement, but in general we do not think the use of such material would either be advisable or necessary.

The use of chalk in any fining action is probably the result of decomposition giving rise to bubbles of CO2, which in turn may assist the finings to move one way or the other, but the process must reduce acidity dangerously.

As a matter of interest, we have examined a number of brewery finings, and determined such figures as nitrogen, sulphurous acid, tartaric acid, etc., with a view to studying the variations that are successfully used in practice. From the following figures it will be seen that they are considerable, and illustrate the fact that the materials used for cutting are not important provided that (1) the fining will remain sound for a reasonable time, (2) the optimum time for cutting is found by experience with the materials used, and no radical alteration made without previous careful experiment.

Summary. — Fining results from the mutual precipitation effect produced when two colloidal solutions of electrically opposite charges are mixed, which is followed by a mechanical separation of the coarser and suspended particles, including some yeast. Although finings exhibit iso-electric points, their normal use does not involve separation from this cause at the concentration used. In so much as an electrical condition of the matter to be removed may be due to the surrounding media, so the reaction, or pH, of a beer does indirectly affect fining. Under normal conditions, and to a greater extent if high fining rates exist, an appreciable amount of fining remains in solution. Isin glass is the second most protective colloid known, and is present in sufficient amount in normally fined beer to exert this effect.

Stabilisation of the colloidal solution remaining may be an advantage, or, alternatively, may check or delay the precipitation of matter which should come out at fining. Irish Moss or similar preparations, act as a precipitant to isinglass fining. Their use for fining beers results in: — (a) Less residual isinglass remaining in the solution. (b) A larger amount of cloud with increased mechanical effect. (c) A tendency to prevent stabilisation of undesirable colloidal matter, or, alternatively, to prevent desirable protection of remaining matter. The use of such material in the copper, apart from its purely coagulative properties, may result in a portion passing through to the beer, and taking a part in the fining at a later stage.

References.

“Manufacture of Finings.” A. Hartley. Trans. Instit. Brew., 1890, 4, 43.

“Action of Finings,” by C. G. Matthews and F. E. Lott. (Ibid., 1890, 4, 201.)

“Natural History of Isinglass” (this Journ., 1905, 9, 508.)

“The Manufacture of Brewer’s Finings” by A. E. Berry. (Ibid., 1907, 13, 44.)

“Modern Ideas on Mechanism of Fining Beer and Wine” by J. B. Harrison. Brewer’s J., 1921, 57, 304 300.)

Discussion.

Mr. H. Heron said the authors had discussed the effect of calcium sulphate on finings, and he would like to ask whether it was actually calcium sulphate as such which reacted, or calcium phosphate. He would suggest that the favourable effect of small quantities of calcium carbonate was due to its influence on the pH value of the beer, as the authors had found that the most effective pH value for fining appeared to be 4·8 to 4·9, and as the pH value of the beer was usually about 4·0, any factor which would tend to alter the pH value to the former figure must act favourably. He thought that fining difficulties were being experienced this year to a far greater extent than had been anticipated, and these might be accounted for by the use of slack malt, the slackness being due to the difficulties of storing during the very humid conditions that had prevailed.

Mr. P. Rowe asked if there was an explanation of the cause of a beer being drawn bright in glass becoming hazy on standing, and on shaking up again becoming brilliant.

Dr. Oliver said he would expect that the beer was in a fairly high condition.

Mr. Rowe agreed.

Dr. Oliver, continuing, said that this probably accounted for the temporary separation of protein, which, on agitation, went back into solution.

Mr. L. E. Simpkins said he understood that two samples of finings made from different kinds of isinglass acted differently on the same beer in regard to pH value. If there was not a certainty of getting the correct pH value for the beer, would it not be best to cut two samples together, say Long Saigon and Brazil Pipe?

Mr. W. J. Watkins said refining was perhaps not important from the point of view of the authors, but he thought that it was in many breweries where the cellars were too small for the trade, and fined casks often had to be moved more than once before setting up on thralls. Was it a fact that some isinglass finings would refine beer five or six times, while others would not refine at all? For instance, was this the difference between finings made from, say, Brazil Lump and Long Saigon Leaf? He also hoped to have heard more about what was commonly known as copper fillings. He believed that they were used extensively these days.

Mr. Harman said that as far as the copper was concerned, the effect of Irish Moss was to help first in the coagulation of the proteins, where the “copper” break was not as satisfactory as it should be; there was no doubt that Irish Moss very effectively helped in the coagulation.

Mr. Watkins said that he had seen worts that broke well in the copper, either with or without the addition of Irish Moss, but only the one with Iris Moss would break after cooling. In the case of a wort which would not break after cooling, the condition of that wort from the point of view of matters in colloidal suspension during and after primary fermentation would not be satisfactory.

Mr. Harman agreed that copper finings were often an advantage. The break in the copper involved among other things the mutual precipitation of protein, and Irish Moss as a definitely charged colloid would be bound to assist. It was noteworthy that Irish Moss not only assisted fining if it survived to the beer, but also precipitated matters that were incapable of precipitation by isinglass finings.

Mr. F. A. Mason drew attention to the variations in the analyses of different sources of brewery finings, and said that he had found that each sort of isinglass required an optimum acidity for cutting which would result in a maximum amount of swelling. Mr. Mason illustrated his remarks with some specimens, showing the effect on isinglass cut at different acidities.

Mr. F. H. Lipscombe asked whether fining made with sour beer had more fining affect than isinglass.

Mr. A. J. C. Cosbie asked if it was admitted that “wild yeast” could hold up fining, and if so, how could such action be explained? He wished to know what the authors considered was the correct time required to make average fining, and what quantity of acid was necessary. The figures stated showed great variations. It would be of interest to know what the optimum pH of finings should be to get the best results, and further, if the authors had ever come across a case of bacterial or other contamination in finings.

Mr. Harman replied in the negative as far as finings cut with tartaric and sulphurous acids were concerned.

Mr. Cosbie stated that Matthews and Matthews, in a paper read before the Institute some time ago, had mentioned a case.

Mr. Harrison asked the authors’ opinion as to what was the best method of fining beer which contained undesirable proteins derived from slack malt.

Mr. W. J. Watkins enquired whether certain finings had the property of re-fining to a greater extent than others, since it was well-known in some districts that this property was ascribed to Saigon Leaf.

Dr. Oliver said he did not believe that the property of re-fining could be attributed to any particular type of isinglass, but the question was bound up with some other points in connection with the system of fermentation and the conditions of the beer at fining. He believed any finings could be persuaded to re-fine, since the re-fining depended upon the amount of protein matter removed in the first precipitation. If this was small, and the finings separated in a light condition then after, agitation they would settle down again, but on the other hand, if the separation removed a relatively large proportion of the solid matter the precipitate was sandy and re-fining would not occur.

Mr. Smith said that he could support that view, since he had found that varieties of isinglass other than Saigon would re-fine four or five times, although he had noticed on each occasion that the precipitate became increasingly sandy.

Dr. Oliver, in reply, said that one of the possible actions of calcium sulphate involved this reaction with the considerable amounts of phosphates present in the malt. Calcium phosphates had a different dissociation constant to those of potassium, and the general effect would be to alter the reaction, and, with it, to some extent, the degree of protein formation.

The blending of finings from different isinglass might be a useful expedient, but as this introduced some special difficulties, he thought that a little experimental investigation would reveal one type of finings as the more suitable for any one beer.

Matthews and Lott had regarded hop resin as an agent which assisted fining, but whereas there was no doubt that hops were responsible for a certain amount of coagulation of protein, and in this way helped fining, it had been found that resin itself was affected generally to a very little extent by finings. This could be illustrated by attempting to fine a hazy pressing in which there was an unusually large amount of hop resin. It was impossible to fine directly with finings, and as the resin was probably present in the state of salts, it was very likely that this was due to the resin particles not being of the correct electrical charge for mutual precipitation with the finings.

In the past finings cut with sour beer were considered better than ordinary finings, but brewers realised the risk their use involved, and, in his opinion, their value had been exaggerated.

The action of wild yeast probably resulted from its capacity for even distribution throughout the beer, with the result that the fining cloud was incapable of mechanically separating it. It sometimes happened that with moderate amounts of secondary yeast infection, the use of auxiliary finings to increase the amount of cloud was often a satisfactory remedy. There was no real optimum pa. for cutting finings, but the amounts of acid required depended upon the isinglass and affected more the time of cutting and the duration of the period for which finings would act than the finings themselves.

Something might be done in the way of encouraging an early vigorous yeast activity in beer by use of a priming, but if excessive or unhealthy protein could not be eliminated in that way or by increased fining, the use of auxiliary finings might prove effective.