MEETING of the NORTH of ENGLAND SECTION, HELD at the MIDLAND HOTEL, MANCHESTER, on Friday, April 27th, 1923.

Mr. R. Whitaker in the Chair.

The following paper was read by Mr. H. F. E. Hulton and discussed: —

HEAD RETENTION IN BEER.

By Julian L. Baker, F.I.C., and Henry F. E. Hulton, F.I.C.

Tub striking variations met with in the appearance of the “head” in beer arc well known to all observers, while, next to brightness, it is probably the visible factor which most tends to predispose the consumer favourably and the absence of which is most resented. To cite only a few instances: everyone is familiar with the characteristic compact permanent head carried by Continental beers fermented by bottom yeasts, the loose bladdery head often seen on English beers, the evanescent small-bubbled foam on champagne, and the “soap suddy” permanent froth (due to saponin or other “heading” preparation) of brewed ginger beer. Even in the case of bottled beers, which show a better head than draught beer, regularity in this feature is seldom conspicuous. The factors upon which good head retention in beer depend are probably as obscure and as difficult of identification as any with which the brewer is concerned and, so far, we have no definite knowledge as to whether it is a property which can be considered as having a single cause or if it is the resultant of many separate factors. Moreover, there is the further difficulty that it is not a constant to which a numerical value has hitherto been attached like colour, alcohol content or acidity; it thus remains at present among that important class of qualities such as flavour, palate fullness or aroma, and the other elusive properties of beer which escape precise definition or numerical evaluation. The well-known investigator, F. Emslander1, in a recent summary of the present position, indicates how little is really known about the matter and he is unable, definitely to assign responsibility to any one single factor among those involved. Neither is A. Fernbach2, who has lately written on this subject (ibid. p. 828), more helpful.

An examination of the literature shows that among the many items which are believed to influence head retention, either favourably or adversely, the following have been cited: —

- The water used for brewing and the salts present in it. or, added to it, for hardening purposes.

- Character and slackness or otherwise of the malt used and the extent to which such malt is diluted with adjuncts, more especially maize.

- Mashing temperature and degree of attenuation of the wort.

- The amount of carbohydrates, particularly dextrin, in the beer.

- Character and amount of the albumoses and other permanently soluble (uncoagulable) nitrogenous wort constituents.

- Presence of substances which lower the surface tension.

- The size of the protein particles present in the finished beer.

- Nature of the hops employed and the hop rate.

- Temperature at which the finished beer is kept in cellar before consumption.

- Chilling and filtering process employed and the method, temperature and amount of gas used for carbonation.

- The reaction of the beer, i.e., its acidity as measured by hydrogen ion concentration (PH value).

- Presence of traces of the higher alcohols formed during fermentation.

- Presence of traces of fat or oil derived from the brewing materials employed.

- Viscosity of the beer. Nature and amount of the finings employed and of the acid used for their manufacture.

- The priming and gyling employed.

- The character of the yeast used for fermentation.

A glance at the above list of factors, all of which at one time or other lave been believed to play a greater or less part in modifying the character of the “head,” makes it at once evident that the problem of improving head retention (if defective) necessitates the systematic investigation of a large number of variables in order to discover which of them are the most important. If it be found that the really essential factors can be reduced even to three or four, much skill and ingenuity will still be required in order to secure their successful balance, while it may possibly be found that some of the essential factors, from the very nature of the brewing process, lie beyond the control of the brewer.

Before discussing the voluminous literature, which deals with the considerations mentioned above, it will be helpful at this point to allude to a few general physical principles underlying the formation of foam in liquids. In any liquid, the particles which compose the surface layer exhibit certain differences in physical properties from those which make up the bulk, chief among which is the phenomenon known as “surface tension.” When a drop of rain-water hangs on a railing it is easy to see that the outermost surface in contact with the air behaves as if it were a sort of clastic membrane of considerable tenacity enclosing the contents. The tension thus set up in the outer surface is known oh “surface tension,” and exerts a measurable force differing for each liquid and also with the nature of the substance in contact with it. If now, instead of considering the case of pure water, some substances such as malt-extract or soap be dissolved in the water two principal effects are produced, viz.: (1) the concentration of the dissolved sub stance in the surface layers of the liquid is greater than in the bulk of the liquid and (2) the surface tension of the liquid is lowered, thus facilitating froth production.A Surface tension in liquids can be measured, among other ways, by noticing the height to which the liquid will rise in a thin capilliary tube, whilst anything dissolved in water (such as saponin, soap or malt extract) which lowers the surface tension will diminish the height to which the water containing it will rise in the tube. Peptones and albuniosesB as well as soap, possess the property of lowering the surface tension of a liquid when they are dissolved in it, in fact, froth production is the direct expression of such reduction, while the concentration of the froth-making material (in beer, e.g., the peptones and albumoses and probably dextrin) is greater in the surface layers of the bubbles than in the bulk of the liquid which supports them.C This phenomenon is well seen in the case of heated milk, or soluble starch solution in which the concentration of protein or starch in the surface layers forms the well-known “skin.” Three main factors are thus seen to contribute to head formation in beer. Firstly, tin lowering of surface tension necessary for the actual formation of head; secondly, the gas (carbonic acid) affecting mainly the volume of the head; thirdly, the extent to which the matters dissolved in beer when they become concentrated in the froth, form membranes or surfaces of notably greater toughness than the liquid itself, thus ensuring persistency of head [Hatechek3; Freundlich4].

A There are other substances which when dissolved raise the surface tension and then their concentration in the surface layers will be less than in the bulk of the liquid.

B Products formed by the breaking-down of barley proteins during malting and mashing.

C To such an extent is the concentration of abluminin creased in the surface layers, i.e., in the froth that a solution of this material was capable of being entirely freed from albumin by mere shaking. (Ramsden)

The distinction between head formation and head retention is one that must be clearly borne in mind, for the property of mere head formation—which is rarely deficient in properly made beer—is of little or no use without head retention, and it is this latter point in which failure is so often encountered. An analogy of some interest is presented by the fermentation which dough undergoes before the loaf is baked. Here also gas formation and gas retention are the outstanding features of importance, but the former is powerless to ensure a large well aerated loaf unless the composition of the dough is such as to ensure retention of the gas at the critical time and much laborious research has so far failed to solve the problem in its entirety.

In making an attempt to systematise the voluminous literature already published on the subject of this paper we have found it convenient to subdivide the numerous factors which are alleged to be involved under the following headings: —

Group I.

(a) Saline constituents.

(b) Acidity,

(c) Carbonic acid and method of carbonation.

Group II.

(a) Malting and mashing.

(b) Finings.

(c) Hops.

(d) Factors detrimental to head retention,

(e) Composition of foam.

(f) Character of yeast.

Group Ill.

(a) Filtration.

(b) Size of protein particles,

(c) Viscosity.

Group I.

(a) Saline Constituents

A. E. Berry5 says that experiments made by him on the use of hardening salts in brewing liquor tended to show that improvement is effected in head retention if sodium and calcium chlorides in amounts not exceeding 30 to 40 grains per gallon were added in the copper, but if these salts or gypsum were present to a larger extent bad effects were produced, owing in all probability to their action in precipitating some of the nitrogenous matter in beer, upon which foam formation depends.

(b) Acidity.

In recent years the old method of measuring acidity in beer by means of litmus paper has to a large extent been replaced by a new technique. Bio-chemists now estimate the acidity of a medium intended to support low forms of life, such as bacteria and yeasts, in terms of the electrical conductivity of the solution. This conductivity (hydrogen ion concentration or pH value) is not the same as the acidity found by litmus, and the trend of modern work goes to show that this pH value is of some importance as a factor in head retention. In the opinion of A. E. Berry5, the effect of acidity is important: samples of beer were taken and the head retention noted from day to day while the acidity was gradually increased until the head was almost entirely destroyed. From 0·05 to 0·1 per cent, there was no decrease, but directly this percentage was exceeded head retention fell until the beer reached 0·3 per cent., when it was distinctly flat. As beer increases in acidity the carbonic acid bubbles become larger, giving a coarser and less attractive head. It was found that lactic acid has not the same deteriorating action on head retention as acetic, though even with lactic acid exceeding 0·l per cent, it is detrimental.

Rohland6 remarks that only those liquids which contain colloids together with free acidity or alkali, yield a strong permanent head when shaken. Beer and beer wort fulfil these conditions, which are lacking in aerated waters or sparkling wines, the head on which is very short lived.

(c) Carbonic add gas.

The effect of carbonic acid on head retention has to be considered from at least three points of view, namely: (1) Gross amount present in the beer, which undoubtedly affects the actual volume or amount of the head; (2) the method of its introduction; and (3) the question as to whether the gas is present in chemical combination or as a mere solution.

I. Carbonation

Hatschek3 in an important paper dealing with Colloidal Chemistry and Brewing, states that he could not describe any detailed method whereby beer could be induced to keep its head better, but he could enumerate the factors which would have to be investigated separately if the question were to be put on a sound scientific basis. There were two main factors: first of all, a certain large amount of carbonic acid in the beer was necessary, and the presence of other substances in solution affected the solubility of carbonic acid. The solubility of carbonic acid was less in dextrin solutions than in water alone while in protein solutions it was about the same as in water. This was the smaller part of the problem as it was always possible, he thought, to get as much carbonic acid in beer as was required. The question was really: What were the influences at work when the carbonic acid came out?

Langer11 says that small differences in the temperature of carbonation between 0° and 50 C. have much effect on the head retention because they influence the solubility of carbonic acid. Less than 0·32 per cent, by weight (1,656 cc. per litre) of carbonic acid gives rise to complaints. Better absorption of carbonic acid results from lowering the temperature than raising the pressure.

The question of the solubility of carbonic acid in beer has been recently treated from the quantitative standpoint by us7. In a paper on the carbonating and filtering process, H. Abbot8 expresses the view that the gassy condition of some bottled beers, where the head is not creamy and feathery and in which the gas comes out too fast, is probably due to the temperature not having been low enough for the beer to absorb carbonic acid during carbonation so thoroughly that it will come out quietly when the bottle is opened, while bad head retention may also arise from too prolonged storage at a fairly low temperature, thus robbing beer to a certain extent of those constituents necessary for good head retention. As a general rule, the condition obtainable in cask is not sufficient after filtering and chilling, and to ensure good head retention it may be necessary to supplement the condition with added gas. Some beers, however, will not stand this additional carbonation since the two gases do not seem to blend well. Carbonating beer and water are entirely different propositions. A beer which has been rapidly forced into condition by a “Krausening” process pours out gassy with a large head which comes and goes quickly, but with slow conditioning the beer pours out quietly and the head continues to increase owing to the slow rise of the gas. It is this latter condition that is desirable in carbonated beer and it can only be achieved by slowly coaxing the gas into it at low temperature and low pressure. Abbot considers that it is most important that no air should be present in the carbonic acid used, otherwise, although the beer appears to be full of gas, it carries no head at all. Very little air makes a lot of difference and even 0·5 per cent, should not be present. Ihnen9 says—and in this we can confirm him—that foam-retaining qualities are favourably influenced by a high percentage of carbon dioxide; the danger of over-bunging or over-carbonating bottled beer has been considerably over-rated, and an increase in the quantity of dissolved gas will materially improve the foam-retaining, quality, even if the other factors remain unchanged. One of the best samples examined had a foam-returning capacity of over 30 minutes and contained 3,170 cc. carbon dioxide per litre, total proteins 0·27, coagulable proteins 0·01, non-coagulable 0·26, dextrin 2·23, extract 4·45, alcohol 4·07 per cent, by weight. This beer, on standing in open bottle for 30 minutes, lost 320 cc. carbonic acid per litre and still had a foam-retaining capacity of over 20 minutes. Another beer, originally containing 2,634 cc. carbonic acid per litre and 0·37 per cent, of total proteins, had almost as good a foam-retaining capacity as the first, but after standing in open bottle for 30 minutes, with loss of 320 cc. carbonic acid per litre, the foam-retaining capacity fell to 9½ minutes. Thus, the view that a high percentage of protein is a necessary condition for good foam-retention is not upheld. The influence of proteins appears to depend rather on the quality of the proteolytic products than on the quantity of total protein. Beers practically identical as regards content of carbon dioxide, total protein and dextrin, may be quite different in foam retaining quality. The percentage of dextrin plays an important part. Although no fixed rule can be laid down, owing to the variable factor of the qualitative value of the proteins, it is generally the case that under similar conditions as regards carbon dioxide and protein-contents, those beers which are rich in dextrin retain the foam better than those poor in dextrin.

Fernbach10 in a discussion on the whole question of the head in beer makes among other statements the assertion that the persistency of the head, which is due to non-confluence of the bubbles forming it, protects the beer from contact with the air and retards the disengagement of gas by preventing the decrease of solubility which would result from such contact. We may say here that we have frequently noticed this phenomenon, for if a glass or carbonated bitter beer be poured out and carefully observed with the light behind it, a stream of upward rising bubbles can be seen, which as soon as they reach the lower surface of the head remain there to reinforce it, and are prevented by the head from all contact with the superincumbent air.

Emslander1 says that practical men have for long known that the head-retaining power of beer is in strict relation with the fullness; and, in fact, the two properties have the same cause, that is the spreading power of the emulsoid protein matters and hop resins which form an envelope round the extremely fine bubble of carbonic acid gas, which prevents it bursting. With the “head” of beer as with the palate-fullness it is a question of an emulsoid system and all that has been said on the subject of fullness applies also to “head,” only here it is the carbonic acid which forms the disperse phase. When the gas bubble sparkles in the beer two sorts of proteid matter, emulsoid and suspensoid, are directed towards the surface of the bubble and surround it. The dextrins likewise increase the resistance of the bubble. In these phenomena it is a question of the intervention of traces of substances. As Freundlich has shown, 3 X 10~7 grm. of peptone for a surface of one square centimetre suffice to form a resistant pellicle and produce a persistent froth. The thickness of these pellicles attains three-thousandths of a micron.

Fernbach2 says, that however the foaming characteristic of beer and the causes which lead to a satisfactory or defective head may be explained, the indispensable factor for its formation is the presence of carbonic acid gas. Failing a sufficient quantity the head will be too small and not lasting. It is, therefore, necessary that beer after its primary fermentation shall be placed under such conditions that the gas once made shall be retained in solution in sufficient quantity to produce good head. With this point of view, we cannot entirely agree, as we have found that beer practically devoid of carbonic acid will produce a most persistent head as the result of more agitation.

The temperature at which carbonation, either natural or artificial, is effected without doubt of cardinal importance, for, as is well known, carbonic acid is far more soluble at low temperatures than high. If a beer is carbonated at low temperature and subsequently kept cool there will obviously be a much higher percentage of this gas available for disengagement when the temperature of the beer rises at the time of consumption. It is more than probable that the well-known excellent head encountered on Lager beer is largely due to the cause. Langer11 says that small differences in the temperature of carbonation between 0° and 5° C. have much effect on the head retention because they influence the solubility of carbonic acid. Less than 0·32 per cent, by weight (1656 cc. per litre) of carbonic acid gives rise to complaints. Better absorption of carbonic acid results from lowering the temperature than raising the pressure. In the Third Report on Colloid Chemistry12 issued by the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1920, the following statement occurs: “The slow evolution of gas from solutions of starch, peptone, and dextrin is obviously of considerable importance in connection with the palatability and sparkling quality of beverages, and if, as it appears, this depends upon the slow diffusion outward from the disperse phase, every facility must be afforded, during carbonation, for the gas to dissolve in that phase. In fact, the beer should, as Langer11 has shown by practical tests, contain a high proportion of residual extracts, and be carbonated at low temperature. The assumption by Siegfried13 of the formation of a carbamic acid which at the higher temperature of the palate gives free carbon dioxide would seem to be unnecessary. The formation of head is governed by the rate of effervescence, the increase being greater, the greater the concentration of colloids within limits obviously determined by viscosity.”

Petit14 also emphasises this question of temperature where artificial carbonation is employed. He considers that the temperature of the beer must be kept in the region of 32° F.—rather above this temperature than below—and that after injection the beer should be kept in contact with carbonic acid at a low temperature and under pressure for two days. As a matter of fact, these are the conditions usually employed in the chilling and filtering system.

II. Method of carbonation.

There are two general methods for introducing carbonic acid into fermented beer. The one most commonly used is to pass the gas into the chilled beer, the latter being well agitated so that a considerable surface is exposed to the gas. Other processes, of which the Lamsens’ is a type, depend on saturating the beer with very small bubbles of carbonic acid gas discharged through porous plates or cylinders entirely immersed in a large volume of the beer. Our own experience of this second type is distinctly favourable so far as good “head” goes, but it is a slower process than the former. O. M. Lamsens15 states that it is well known in carbonating beer the amount of gas absorbed depends not only on the temperature and pressure of the beer and the chemical properties, but also on its physical condition. The less it is agitated during carbonation the more gas it absorbs, while for rapid absorption there should be intimate contact between the gas and the beer over the greatest possible surface. The last-mentioned condition can be realized by injecting the gas below the surface of the beer in very fine bubbles, or by spraying the beer in a vessel containing the gas. The former method is much to be preferred since it agitates the beer less than the latter.

Petit14 has recorded observations on the carbonation of beer with carbonic acid obtained from fermentations and also with gas artificially prepared. In the latter case the results were not satisfactory, since the beer gave up its dissolved gas too readily and only had a large bubbly head which quickly subsided. It was subsequently found that satisfactory results could only be obtained by using carbonic acid obtained as a product of fermentation.

III. Chemical combination.

O. Mohr16 carried out experiments which indicate that there is no difference as regards the retention of carbonic acid gas by beer, whether the gas has been absorbed as a product of fermentation or forced into the beer from outside. No grounds, he states, have been discovered for justifying the assumption that the gas is retained in the beer in combination, and it appears to be purely a matter of solution; moreover, the presence of viscous substance assists beer in retaining carbonic acid.

Langcr11 has carefully considered the matter of chemical combination vs. solution and concludes that the absorption of carbonic acid by beer, although mainly physical, also depends on the formation of loose chemical combinations between the carbonic acid and the constituents of the extract. No doubt the physical retention (adhesion) of the carbonic acid by the beer is not only greatest quantitatively but also of chief importance from the point of view of condition. Thus the sparkle and the condition of the fine-bubbled, compact “head” is due to the retardation exercised by the physical viscosity and surface tension of the extract constituents upon the escape of the absorbed gas. The “pricking” sensation on the tongue is due to the super saturation of the beer with the gas and is purely physical. But the full smooth flavour of a well-conditioned beer is due rather to the decomposition of unstable chemical combinations between extract constituents and carbonic acid, at the increased temperature of the mouth. The nature of the combination in question has not been fully investigated, but Kjeldahl has shown that the base choline, which combines with carbonic acid to form such a compound, is a constituent of beer, and Prior17 has demonstrated a reaction between the carbonic acid and the secondary phosphates of the beer with the production of primary phosphates and unstable bicarbonates. This view, however, as pointed out by O. Molir19 appears to be untenable seeing that the mean of these phosphates merely averages 0·07 per cent, (expressed as phosphoric acid) and could therefore fix only 0·03 per cent, of CO2 in the form of bicarbonate. Fernbach2 states there have been many theories of the nature and cause of head. It was thought for a long time that the carbonic acid existed in two forms, free and combined or chemically fixed in a loose way with certain constituents of the beer. The phosphates were considered by Prior to play an important part in this connection. It has, however, been necessary to reject this theory, because beer acts from a physical point of view as all other solutions of carbonic acid and one is led to believe, from a study of beer by modern physical methods, that all the gas is in a dissolved state and that none of it is combined. Physical chemistry has of recent years made immense progress, thanks to the study of colloids, and the present conception is that beer owes its viscosity to the presence of colloids and that these hold the gas by absorption, that is, by a purely physical fixation.

Group II.

(a) Malting and Mashing.

The carbohydrates, so far as published investigations show, only play a subsidiary part in head retention.

Emslander18 points out that amongst the colloids which have an effect in rendering colloidal solutions stable (i.e., prevent coagulation) are the extractive substances of hops, alcohol, and especially dextrine. The observation that worts which, as a result of overheating, are not completely saccharified, generally yield beers of strong palate fullness and head-retaining power led to the view that dextrin is res possible for these properties, and endeavours were directed to the production of beers of high dextrin-content. Through these one-sided methods of working, the protein was quite neglected, and the result was the production of unsatisfactory beers, which, since dextrin is not as a matter of fact responsible for head-formation, wore especially deficient in head-forming power.

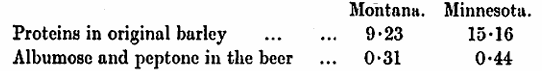

Ihnen9, however, states that in his opinion dextrin itself plays an important part in head retention. We think the balance of evidence appears to show that the carbohydrate constituents of wort, namely, dextrin, maltose, glucose, &c., are only indirectly factors in favour of head retention, in so much as they help to stabilise the colloids in solution. If the conditions which influence head retention are to be sought for in the composition of the wort it is in the direction of the proteins that we must turn our attention. It is almost the unanimous opinion of investigators who have worked on this subject that the peptones and albumoses are the essential factors underlying head retention. It is these substances in particular which have the property when in solution of lowering surface tension and thus facilitating foam formation. These peptones and albumoses do not exist ready-formed in the barley but are produced during malting by the agency of proteolytic enzymes, and, to a further though less extent, in the mash tun. O. Mohr20 makes reference to the head-retaining capacity of solutions of peptone when unfiltered, but notes that while foam formation survives filtration, retention is almost entirely destroyed. R. Wahl21 brewed two beers of different nitrogenous composition: —

The high nitrogen (Minnesota beer) proved to be the better from the point of view of palate fullness and permanence of head. A. Stange22 carried out a similar experiment with Russian barleys and came to an identical conclusion.

Schönfeld23 has described an interesting experiment in which he stored malts under conditions which caused them to become very slack; the final moisture-content rose to 10 or 11 per cent, and was originally 2·7 per cent. It was found that the slack malts yielded less albumose nitrogen when extracted with hot or cold water, while the head retention of the worts made from the slack malt was very inferior, which is in conformity with the theory that enzymic degradation of the proteins in presence of moisture had continued to a point beyond the formation of the desirable albumoses and peptones.

Emslander and Freundlich24 state that the colloids of beer are the cause of the qualities known as “permanence of head,” and “palate fullness”: these two qualities go side by side, both disappear by frequent and too perfect filtration, and both are allied to a high internal friction (viscosity). These qualities depend on the colloidal albuminoids and peptones.

According to Horace Brown25 the cold water extract of malt contains half of its nitrogen in the form of peptones and albumoses, but in brewers’ wort the total amount of proteins going into solution will be some 50 to 60 per cent, more in quantity than those which are dis solved from the malt by cold water, owing to the further proteolytic action which occurs during mashing. Foremost in importance among these albumoses is that described by Horace Brown as “Malt Albumose I,” about which he writes26: “The power of producing a persistent froth was confined to the smaller fraction, malt-albumose I, which was insoluble in 85 per cent, alcohol; the soluble fraction, malt-albumose II, did not possess this remarkable property. This is a fact of considerable interest in connection with the formation of the ‘head’ or foam on malt-worts and beers, and will require further investigation from this point of view.” In reply to a question in the discussion which followed the reading of a paper on “The Nitrogen Question in Brewing”25, Brown said nothing definite can be asserted about the effect of albumose I during fermentation, but it seemed probable that the head of worts and beers was not entirely due to the presence of this substance.

Lintner27 claims that the albumoses and peptones (which present a relation to the proteins similar to that of the dextrins to starch) are considered to be responsible for the head-forming power of beer, and even in very dilute solutions these substances give a very abundant and durable head. The sols of albumin and malt globulin, however, possess this property in still greater degree. If the assumption is justified that in a malt which yields a beer of poor head-forming power the proteins have suffered excessive degradation, a decomposition of globulins into albumoses, as well as of albumoses into amides, should be taken into account.

Fürnrohr28 has studied this problem and considers the formation of a lasting head on beer depends very largely upon the presence of certain nitrogenous substances, mainly albumoses. In order to produce a beer capable of holding a good head it is therefore necessary to limit the proteolytic changes which occur in the mash, so that the albumoses shall not be completely decomposed into less complex compounds. Among the intermediate products formed during the degradation of proteins, Kühne distinguishes primary albumoses and deutcro-albumoses. The former are distinguished by being precipitated by copper sulphate: they are not far removed from the true proteins. The deutero albumoses cannot be sharply distinguished from the peptones, which represent a further stage of proteolysis. In order to study the relation of head retention to protein-content of beers, the author made use of three methods of salting out, characterised by the use of copper sulphate, zinc sulphate and phosphotungstic acid. In all cases 50 grms. of beer or wort were treated first with one drop of concentrated sulphuric acid and then, as the case might be, with 15 grms, of copper sulphate, 55 grms, of zinc, sulphate and 10 c.c of a concentrated solution of phosphotungstic acid. The liquid was allowed to stand for 24 hours before the precipitated protein was filtered off. Beer salted out with zinc sulphate was found to have lost much of its head-forming capacity, and when the precipitate thrown down was shaken with distilled water the latter frothed readily. Since zinc sulphate precipitates mainly the true albumoses, these results indicate that foaming is largely due to these products of proteolysis. He suggests that, in view of the importance of albumoses for the formation of head on beer, experiments on the lines of those described in the present paper should be carried out in order to ascertain the conditions for mashing best calculated to ensure a sufficient quantity of albumoses in the finished beer. [See also Ihnen9 and Zeidler and Nauck42.]

We cannot but feel that, in view of the importance which, as is well known, brewers attach to mashing heats, it should be remembered that the temperature of the mash has considerable influence on the nature and amount of the protein substances (albumose, peptones, &c.) formed under the influence of the proteolytic enzyme during mashing. The optimum temperature for the formation of such bodies is considerably lower than that obtaining in the mash tun, and their production is much restricted in the neighbourhood of 150°F. W. Windisch29 states that in order to obtain the particular proteolytic cleavage products concerned in head formation the temperature of the mash should not rise above 154°F. in the earlier stages. It is thus evident that a brewer cannot expect to combine high mashing heats with the maximum production of uncoagulable proteins, and, in so far as head formation is dependent on such bodies, he is to that extent handicapped. Fortunately, however, the larger proportion of the peptones and albumoses in his worts has already been produced in the malt as a result of protein degradation during the flooring process.

(b) Finings.

The only reference dealing with the possible effect of finings on head retention is a paper by A. E. Berry5. He is of opinion that the too early addition of finings adversely affects head retention, especially if sulphurous acid is present in the finings; he is in favour of the delay of the addition of finings in cases of flatness as long as possible. Different types of finings may considerably improve head retention, since they contribute colloids of a nature that remain in solution, as may easily be seen by carbonating an emulsified form of isinglass in water and observing the head.

(c) Hops.

Heusz30 states that the work of previous investigators tends to show that the protein content of beer wort is slightly diminished by boiling with hops, apart, of course, from the precipitation of albumins which would be coagulated by boiling even without hops. The retention of head by beer has also been shown to be favourably affected by boiling with hops, but this effect appears to be due, not to the proteins, but to the hop-resins. His own experience shows that the amount of protein matter extracted from hops by boiling water is extremely small, and represents only about one-tenth of the total nitrogen extracted. Further experiments which this author made upon the foam-holding capacity of unhopped worts, hopped extracts, and mixtures of the two, showed that the column of foam formed on the mixed extracts was twice as high as that on the malt extract alone, and it was far more lasting than the latter.

Quite recently Luers and Baumann31 described some researches on the properties of the acid of hop bitter or Humulon (hop bitter acid), and find that its power of producing a stable form is in keeping with its power of reducing surface-tension.

(d) Factors Detrimental to Head Retention.

Every chemist is familiar with the device of adding a drop of ether or even a little ether vapour to a liquid when he wishes to dissipate an inconvenient fobby head, while the effect of oil on troubled waters is proverbial. When considering the factors which make for good head retention it is necessary not to overlook the possibility of substances finding their way into beer which may be actually deleterious to foam formation. Such substances fall into two groups: (1) Certain higher alcohols and their esters produced as a result of fermentation, and therefore normally present in minute amounts, and (2) traces of oil or fat derived from the grist or otherwise obtaining access to the beer from the vessel containing it.

Bau32 states that the most active of those substances are amyl alcohol and secondary octyl alcohol, both of which are fermentation products and have such a powerful effect that a single drop suffices to dissipate the head, the gas being expelled with brisk effervescence. The corresponding aldehydes and acids are almost equally active.

Berry5 states that the higher alcohols have a most destructive action upon the foaming capacity of beer, and he has no doubt that the flatness in some breweries is due to the fact that certain foreign types of yeast are present during attenuation which afterwards give rise to these higher alcohols, and accordingly act disastrously on the head. For instance, amyl alcohol, amyl acetate, fusel oil, and several other alcohols and esters, even when present in exceedingly minute quantities, have a crippling action upon the foaming capacity. He made experiments by adding very small quantities (fractions per cent.) of the different alcohols to beer in good condition, noticing the flattening effect, but the results were such as to make it highly desirable, when flatness occurs in a brewery, to look to the presence of foreign yeasts and ferments that would be likely to produce higher alcohols.

This same point of view is emphasised by Luers Geys and Baumann33.

Bau32 (loc. cit.) considers that fats which are generally regarded as a cause of loss of head have much less influence in this respect than have the higher alcohols, while Berry5 (loc. cit.) states that, speaking generally, the foam-destroying constituents of beer are chiefly of an oily character, and arc so objectionable in their behaviour that, even when mixed with other bodies that would be favourable, they have the power to counteract them. He is strongly of opinion that the oil from maize, barley, and other cereals has a very prejudicial effect on the foaming capacity, and, of course, they are equally objectionable from the point of view of palate-flavour and fullness. The essential oil of hops does not act in such an unfavourable manner. Every brewer is aware of the importance of keeping at a minimum the percentage of oil in maize, but with decreasing gravities, and whenever flatness is apparent, the percentage of oil in the goods that are being used is a point that should certainly not be overlooked.

Nowak34 states that the efforts of the brewer to ensure the presence in beer of those decomposition products of proteins and carbohydrates on which the formation of head depends will be of no avail unless equally great care is taken to ensure that after leaving the bottle the beer docs not come into contact with substances which will destroy the foam. Among substances which have this effect are fats of all kinds: exceedingly email amounts of fatty or oily matters such as may be present on the surface of an apparently clean glass affect the surface tension of beer and may cause a rapid collapse of foam. He cites a case where the head of a beer which collapsed when put in an apparently clean glass was retained quite satisfactorily after the glass had been thoroughly cleansed with alkali, and states that it is not enough to rely on the apparent cleanliness of glasses which may previously have been used for milk, &c.

According to Dreesbach35, when adjuncts such as maize and rice are used in brewing, part of the oil they contain becomes emulsified by the extractive substances during boiling in the copper, and thus pass into the wort, and, during fermentation as the sugars disappear, they are again set free to affect flavour and head retention detrimentally. The effect of oil on the head-retaining power of beer is too well known to require further description, and it is evident that the less oil a beer contains the greater will be its head-retaining power, especially in the case of a pasteurised bottled beer.

(e) Composition of Foam.

Although so much has been written about foam formation in beers it does not seem to have occurred to any worker until 1920 to make a chemical and physical examination of beer foam itself. For this purpose, Luers, Geys, and Baumann33 collected a large quantity of foam from six different beers of original gravities varying from 1017 to 1044 degrees and allowed it to subside in glass vessels. In this way several litres of “foam beer,” consisting of collapsed foam, were obtained from each of the six beers. These “foam beers” were subjected to analysis, including estimations of total nitrogen, amide-nitrogen (formol titration), acidity, volatile acids, esters, surface tension and viscosity, and samples of the corresponding original beers were similarly analysed for purposes of comparison. The results showed no significant differences in alcohol-content or extract-content between the “foam beers” and the original beers; such differences as were observed were irregular and probably due to evaporation of alcohol from the foam and to precipitation of certain constituents in the foam, for the “foam beers” contained insoluble flocks or skins. In general, the foam contained more total nitrogen, but considerably less amide-nitrogen than the original beer. The total acidity was also somewhat higher in the foam than the beer, and the volatile acidity was much higher, from 2 to 10 times as great. The surface tension of the “foam beer” was in all cases lower than that of the original beer, whilst the viscosity exhibited no uniform difference, being somewhat higher in some cases and lower in others, possibly owing to separation of certain constituents of the foam in an insoluble state. The hop bitter acids must also have accumulated in the foam to a certain extent, for the flavour of the latter was intensely bitter. It was observed further that the “foam beers” were not clear, but contained flocks and films of protein substances in suspension. This is accounted for by the well-known fact that colloidally dissolved substances such as proteins, when concentrated at the surface of a solution or in films, tend to pass from the state of sol to that of gel, and eventually to form a thin skin. This greatly strengthens the films of which a froth or foam consist, and is a most important factor in the retention of head on beer. It is the presence of these gelatinised colloids in beer foam which prevents it collapsing at once, as the froth on lemonade collapses.

O. Furnrohr28 has observed that the proteins present in beer retain in solution certain constituents of the hops; especially noticeable is this in the foam of beer which is richer in proteins than the liquor itself, and in the case of strongly hopped beers such as Pilsen it was often observed that the head possesses a more bitter flavour than the liquor.

(f) Character of Yeast.

F. Schönfeld and H. Rossmann36investigated the degree to which the specific properties of top fermentation yeasts arc retained or influenced by subsequent cultivation from single cells. The capacity to produce good head was found in rare cases to diminish on further cultivation in wort, but oftener it was found that cultures giving weak heads came up much stronger in this respect by cultivation in fresh wort, while addition of sugar solution to the wort usually had a deleterious effect. They concluded that yeast which possessed strong head producing power transmitted this characteristic fairly constantly and regularly.

Group III.

(a) Filtration.

Filtration, so far as it affects the head-retaining properties of beer, was first studied by O. Mohr20. He observed that a solution of commercial “peptone,” which consists mainly of albumoses, possessed a most remarkable power of retaining a “head” of froth when in the unfiltered and slightly turbid condition, but that after the solution had been filtered it lost this property almost entirely, although the capacity for forming a froth remained unchanged. This observation suggested that the “’head’ retaining property was due to minute undissolved particles which were removed by filtration.” When a little zinc sulphate was added to the filtered solution, so as to produce a slight precipitate of albumoses, the power of retaining “head” returned. Permanence of head in Mohr’s opinion depends on the presence of suspended colloidal bodies of a protein nature in an infinitely fine state of division. Windisch37, commenting on Mohr’s views, discusses the effect of the possible removal of such particles by the nitration of the beer. He cites cases in which the introduction of the filter into the brewery has caused undoubted deterioration of the quality of the product (a) as regards permanence of head, (b) as regards fullness and purity of flavour. This is especially noticeable in cases where the breweries have been noted previously for some exceptional character of their beer, since filtered beers all tend to a common level of quality. The public taste has now been trained to demand beers of such brilliancy as can only be attained by very perfect filtration, and the competition to satisfy this demand has led to the result that modern filtration is too perfect. In the early days of the beer filter, owing to the loose packing of the filtering medium, a small filter could purify a relatively large quantity of beer to a sufficient degree of brilliancy. But in recent years the density of the filtering medium has been so enormously increased that the minute colloidal bodies referred to above are probably mostly removed.

Ludwig38 agrees with Windisch and states that the surface of the cakes of pulp rapidly becomes coated with a layer of suspended impurities, through which the beer has to be forced under enormous pressure. The constituents of this layer of impurities are far more soluble in beer at high pressure than at moderate pressure, and since the impurities have been deposited under a pressure of about 0·5 atmosphere in the lager tun, they are partially re-dissolved when the beer is forced through them at a very high pressure. Hence the characteristic unpleasant “filter” flavour of filtered beers. The ideal system of filtration would be one in which the impurities were removed in a series of progressive operations under a low pressure, thereby avoiding the accumulation of impurities on the outer surface of the medium.

Franke39 also emphasises the desirability of not packing the filters too closely.

O. Furnrohr28 states that the power of retaining a good head is more or less diminished by the filtration of beer, and this was confirmed by the author’s experiments, which showed also that albumoses are retained by the filter pulp, so that the quantity of these in the beer may be seriously diminished by filtration.

(b) Size of Protein Particles.

It will be remembered that the concentration of the head forming constituents in the froth of beer is greater in the surface layers of the bubbles than in the bulk of the liquid. There in good evidence for the belief that such head-forming bodies are chiefly the peptones and albumoses, and the permanence of head therefore depends on the presence of these suspended colloidal bodies in infinitely fine state of division.

Mohr20 considers these particles probably form a network around the bubbles of carbon dioxide, preventing them from uniting to form larger bubbles. These particles must be preserved in the finest possible state of division, since it was found that if the unfiltered “peptone” solutions were allowed to remain until partial aggregation and sedimentation had taken place, the “head” retaining properties gradually disappeared. In the same way, any influence which tends to produce aggregation of such particles in beer, e.g., the production of visible “albumenoid” turbities, detracts from the permanence of its “head.” The practical bearing of filtration upon the “head” retaining properties of beer requires consideration from this point of view. The suspended particles in a heterogeneous solution of a colloidal body can be observed by an instrument called the “ultramicroscope”; this instrument should be applied to beer in order to reveal the nature, size, shape and number of colloidal particles in conjunction with their influence upon the “head.”

For the next 16 years these views were generally accepted until further experimental work by Windisch and Bermann40 tended to emphasise the importance which should be attached to the degree of fineness as well as to the composition of the particles which cause head formation and retention. These authors bring forward evidence to show that the carbohydrates (dextrin, amylans, etc.) are also concerned in head formation.

Windisch and Dietrich41 have recorded some experiments on the filtration of beer through fine filtering materials of various degrees of closeness. They find that the surface tension, both of fermented and unfermented worts, was practically the same before filtration, but that the changes of surface tension produced by filtration were in all cases in the direction of the surface tension of pure water, and were, in general, the greater the finer the filter. It is, they think, probable that the larger order of colloidal particles in wort and beer contribute more than the smaller ones to the surface tension of the liquids.

Luers, Geys and Baumann33 believe that the capacity for forming foam depends to an important extent on the size of the colloidal particles in a liquid. It has been found, for example, that perfectly clear albumose solutions do not froth well; but addition of a trace of zinc sulphate, which produces opalescence, and therefore causes the colloidal particles of albumoses to coalesce into larger complexes, improves the frothing capacity very much. Again, if pure clear solutions containing proteins, e.g., cold extracts of malt, are heated, they froth very copiously just when the coagulation of the proteins commences, but after coagulation is complete the froth collapses, and the liquid boils quietly without much frothing. In both these cases the colloidal particles in solution undergo progressive increase in size, and the maximum frothing capacity corresponds with a certain size of particles. For beer to possess the maximum head-forming capacity, therefore, it is necessary that the colloidal matters, such as the proteins, should consist of particles of a certain optimal size. Any circumstance which deprives the beer of colloidal particles of this size will impair its head-forming power. This may be brought about, for example, by filtration through too fine a filtering medium, or by excessive proteolysis during mashing. An excessive acidity also tends to reduce the size of colloidal particles in beer, and thus to impair head-formation. On the other hand, the colloidal particles must not be too large. It is well known, for example, that beer which has been rendered cloudy by chilling does not form a good head. The effect of the low temperature is to increase the size of the gluten particles beyond the optimum. Warming reverses this effect, and therefore improves the head-forming power again.

Emslander1 also emphasises the preponderating part that solid particles exert on the formation of froth. In practice this is brought about empirically by brewers, who make use of Krausen or by bunging down with well water. By such means solid particles are introduced into the beer and induce separation in a fine state of division of precipitates of the salts of lime and magnesia.

(c) Viscosity.

This same writer1 (loc. cit.) states that one rightly distinguishes between the formation of “head” and its persistence. Every liquid having a weak surface tension is susceptible of producing a froth, and this is so with all beers containing carbonic acid in sufficient quantity. But the froth, which really is only a gaseous emulsion, only persists in presence of definite substances. It has been thought that the presence of viscous substances suffices to improve the head on beer. Experience has shown that it is nothing of the kind: glycerol, for instance, is very viscous but does not increase the frothing of beer. On the other hand, the addition of traces of egg albumin produces a very marked effect.

Berry5 also recorded experiments with egg albumin and the beneficial effect on the head produced by this material, but indicates the inadvisability of its employment for obvious reasons.

From what has been written so far it will be apparent that to arrive at any definite conclusions affecting the formation and permanence of head in beers brewed under English conditions, a great deal of experimental work will be necessary. A point that strikes anyone who has made, as we have, a systematic research of the literature on this subject is the extent to which writers almost invariably claim an improvement in head retention and palate fullness as the result of adopting whatever change in brewing technique they may happen to be advocating. This, together with a lot of what may be called “armchair theorising,” is far too prevalent, and we have, in the above synopsis, so far as was possible to judge, quoted no writer who has not adduced some experimental evidence in support of his allegations.

During the last few years, we have collected a certain amount of experimental data the bearing of which we are considering, and we hope in a future paper to submit our results to the Institute. It may be of interest to give a brief outline of the work we are now engaged on.

A striking fact comes out that in reading the literature no investigator has attempted to express head retention in a quantitative manner. Little advance can be made on such lines as there is no standard to work to, and the reader is thrown back on expressions of opinion which are qualitative in nature and are therefore unsatisfactory. At an early stage of our inquiry, we were impressed with the necessity of devising what may be described as a standard “pour” and recording the results photographically.

The apparatus we employed was simple. A syphon arrangement was constructed which would deliver a known volume of beer contained in a bottle from a defined height into a vessel of known dimensions. “When the volume was delivered the head was photographed and the time taken for the head to disperse (i.e., when a clear area free from bubbles forms in the centre of the surface) recorded.

As an example of how this apparatus can be applied to the investigation of a single factor, we may instance its use in connection with the influence of carbonic acid content on the formation and retention of head. It has been frequently stated (vide ante) that the presence of a considerable amount of this gas is necessary, and we thought it would be of interest to deprive a beer as far as possible of its carbonic acid by tossing and rousing and then comparing its head with that of the original beer. Two beers were experimented with:

(1) Stock ale of original gravity 1061o contained 916 cc. of carbonic acid per litre. When the fall from the end of the tube into the glass was about 1 ft. only a very slight head was formed. When the fall was increased to 3 ft. the volume of the head was greatly increased. Similar results were obtained after thorough rousing when it contained only 242 cc. per litre, equivalent to a loss of 75 per cent. This would appear to indicate that when working with naturally conditioned beer the head is independent of the gas content.

(2) A carbonated pale ale of original gravity 1042° contained 1,950 cc. of carbonic acid per litre. When the fall was about 12 inches there was a considerable head; this again was greatly increased in volume when the height was increased to 3 ft. When de-gassed great reduction in size of head was found under both conditions, but in the 3 ft. fall the head—what there was of it—was much greater in volume than the 1 ft. fall. It was also permanent.

It is clear from these experiments that if a completely de-gassed beer is sufficiently agitated a considerable and permanent head can be obtained, the amount of head depending on the height of fall from the delivery tube to the receiver. Head, therefore, can be associated with amount of gas and with entire absence of gas. In other words, gas is only one of the factors in the formation of head.

These facts would seem to suggest that one of the functions of carbonic acid in beer in its relation to head is that of acting mechanically as an agitator during its evolution. Another form of agitation is effected by some of the nozzle devices which are attracting some attention in the retail trade. The head obtained by such methods is at the expense of some of the carbonic acid in the beer, and thus the eye gains at the expense of the palate. In fact, by using one of the nozzles it is quite easy to put a head on to a tossed beer which will be permanent for hours.

Laboratory, Stag Brewery, London.

Discussion

The Chairman said he was sure he expressed the feelings of all present when he said that they had listened to a very interesting paper, and there would be no two opinions that the authors must have spent a great deal of time and thought in its preparation. The subject dealt with appealed to them all, for there was no doubt that a glass of beer with a good head would sell better than one without a head. Next to brilliancy, which he thought the public of the present day seemed to look for first of all, a good head on the beer was worth a lot. He was of the opinion that the head on beer commenced with the very first detail of mashing; and then, even if the mashing temperatures and everything else were perfect for making a good head on the beer, it could be spoiled by many other different conditions afterwards. In fact, a good head on beer was a combination of what he might call successful brewing. But even if brewed as perfectly as possible a great deal then depended on the condition in which the beer was sent out for sale, and also upon the way in which the customer handled it when it had been delivered. He worked on the principle that the gas and the viscosity of the wort all tended to confer a good head on beer, and that when a beer was perfectly flat—with no “life” in it—it was very difficult—at any rate with the ordinary beer-pump—to get much result.

Mr. C. F. Hyde said: He had seen in use by many customers a device similar to that shown by the authors: a wire-gauze disc being employed for the purpose of breaking up the beer, at the same time dispersing the gas, giving a frothy glass of ale but with a flat taste. He strongly deprecated the use of any such device for producing head. Palatable ale was most desirable, and preferable, even without a head, to the converse with a head.

The authors had touched lightly on the effects of mashing; he believed that the “head” of beer was mainly due to the mashing process. Another factor was the yeast employed; a stone-square yeast was a good head producer. In the paper it had been suggested that the CO2, had not much influence; he differed from the authors on that point. The nature of plant was a great factor. With the soft moorland waters in Manchester it was a problem—with iron plant—to get a beer to retain its head, especially so if the cast-iron hot-liquor tank reacted to the C02 and oxygen dissolved in the water. There would then be present in the water, in solution and in suspension, hydroxides, oxides and carbonates of iron which in turn would react with phosphates in the mash and give insoluble iron phosphates.

The elimination of iron in suspension or in solution from mashing and sparging liquor would result in better head retention. He had no doubt in his own mind that rusty hot liquor has a most detrimental effect on the nitrogenous constituents of malt liquor. On the other hand, a water containing alkaline earths such as bicarbonate of lime, which on boiling gives the hot-liquor tank a coating of chalk, renders such cast iron hot-liquor tanks free from the disadvantage and admirable for their purpose.

Mr. A. H. Morris said in the case of bottled beer—chilled and carbonated—he had compared beers matured and not matured, filtered and not filtered, and he had been unable to find any difference whatever in the head retention. Neither had he found that the carbonation had had any effect on head retention, and he was driven to the conclusion that the head retention of beer was a matter that was inherent in the character of the beer as brewed, partly as a result of the composition and character of the wort, and partly as a result of the yeast used and the way the fermentation was conducted. He thought that the head retention was probably determined before the malt was put into the mash tun—as a result of the way the malt was grown and the character of the barley used. The slides they had seen seemed to confirm what he had said, that head retention was due to some inherent character of the beers. The head seemed to be equally good whether the beer contained a large amount or a less amount of gas.

Mr. J. Marchant said he understood that most beer drinkers liked to see the head adhere to the glass. He would like to know if the authors had considered that matter.

Mr. F. Hyde said the method outlined by the authors of measuring head was quite simple and within the reach of them all. Looking at the photographs, he though the head that was near perfection was that of the lager beer. Might he suggest two factors which he thought had a bearing on the lager beer head. One Mr. Morris laid emphasis upon was the growth of the malt on the floor; but, of course, in lager beer one used malt not quite so perfect as that intended for ales. Again, the mashing process played a greater part than it did with their ordinary infusion methods. He thought that in lager beer they had the effect, partly, of the mashing process, and in addition they had the effect of the gas coming out of solution.

Mr. E. R. Graesser thought they should go back to the materials they started with, and undoubtedly the barley and malt were the foundations. They might have a good barley, but, unless it was malted properly as for lager beer brewing, they would not have a good head. There was one point on which, it seemed to him, contradictory statements had been made. While the authors stated that lager beers— the Continental beers—were the best head formers, they also stated that filtering took the head away. All lagers were filtered, and he did not know a lager brewery where they were not. It was also said that dextrin did not play any part; but here, again, it should be remembered that lager was richer in dextrin than any other beer, and it appeared to him, therefore, that it must have some influence.

Mr. T. H. Wall said in experiments with which he had been associated he had always found that in a brew of beer divided into two fermenting vats and the final attenuation the same, the wort fermented with Burton yeast carried a better head than that fermented with a Birmingham or Lancashire yeast. In the case where Lancashire yeast had been used, if a glass were filled with beer and stood a minute the head would nearly vanish; but if the hand was placed over the glass, and the glass shaken, the head would remain two minutes. The duration of the head would correspond to the shaking; on the fourth shaking it would last for half an hour.

In reply, Mr. J. L. Baker said the Chairman rightly remarked that the head was the result of practically all the factors involved in brewing— it started from the time of mashing. Mr. Morris went further—and he took it they would all agree with him—that they had, first of all, to consider the malt. A number of interesting questions had been asked, but it would be impossible to answer them all as their paper was largely a survey of previous publications, and although certain statements and theories put forward by other workers had been mentioned it must not be thought that they (the present authors) agreed with all of them. The work of Mr. Hulton and himself had not gone far enough to enable them to say whether they had any evidence that those opinions were correct or not. No doubt some of the C02 was removed from the beer by the use of a nozzle attached to the engine. Many would agree with Mr. Hyde that it was desirable not to use anything that was going to introduce what seemed to be admitted on all sides to be deleterious—viz., air. Those present in the room probably all looked at beer chiefly from the point of view of flavour; he did not suppose any of them cared much about the head—it was an agreeable thing to look upon, but it was not a matter of profound importance. It was somewhat different in the case of the man who consumed beer in a public-house. If he saw a nice head on the beer he thought it was good; and they were forced to take into account this point of view.

Mr. Hyde had also made reference to the effect of plant upon head, and that probably had some bearing, but whether it was related to the amount of disturbance the beer underwent during the fermentation process he did not know.

Mr. Marchant’s views as to the way the head on beer adhered to the glass were of interest and it might be associated with the cleanliness of the glass used, a point which was dealt with in their paper. Mr. F. Hyde referred to lager beer, and thought the head might be connected with the combination of CO2, with the extract. Some work had been done in this direction, but so far as the experiments had gone there did not seem to be much evidence in favour of such a combination. He was interested to hear Mr. Wall’s remarks as to Burton yeast giving a better head than Lancashire yeast in the same wort. He thought possibly this might be associated with the presence of certain by-products tending to diminish the head in the Lancashire yeast fermentation.

A vote of thanks was accorded to the authors for their paper.