MEETING OF THE MIDLAND COUNTIES SECTION HELD AT THE GRAND HOTEL, BIRMINGHAM, ON THURSDAY, 25th FEBRUARY, 1937

Mr. F. G. Burdass in the Chair

The following paper was read and discussed: —

INVESTIGATIONS ON FOAM

By Jakob Blom, D.Ph.

Foam in General

It is well-known that foam is a system of gas bubbles dispersed in a liquid; actually, however, foam is always gathering on the liquid. It is perhaps less well-known that it is impossible to form a foam on a pure liquid. No pure liquid will froth, be it shaken ever so vigorously. Experience shows that foam is formed only on solutions, molecular or colloidal. Thus, while neither water nor alcohol will froth, a mixture of both—when shaken—will form a foam, though not a very stable one. This curious fact is closely connected with some interesting properties of froth-forming liquids, which may be illustrated by a simple experiment of bubble blowing. To blow a soap bubble it is necessary to do work. If the pipe is removed from the lips before the bubble bursts or escapes, the bubble will diminish in size, blowing the air out of the pipe, the bubble now in its turn does work. The work thus stored as potential energy in the surface is called the surface energy, or— expressed in other units—the surface tension. It has a characteristic value which can easily be measured. The amount of the surface energy may be expressed in ergs per sq. cm.; that of the surface tension in dynes per cm.

Like all other forms of free energy, the surface energy strives towards a minimum. In one way a minimum may be obtained by diminishing the surface itself. This is the reason why a bubble or a drop assumes a spherical form, the sphere being the body with the smallest surface for a certain volume. In pure liquids it is the only way of reducing the surface energy; but in solutions—molecular or colloidal—there is another possibility. Two substances rarely have the same surface tension against air; in a solution the surface energy may therefore be reduced if the component with the lower surface tension is concentrated in the surface. This is actually what happens, and in general it may be said: “In any solution the substance with the lower surface tension is concentrated in the surface ” (Gibbs and Thomson’s law). The concentration of the surface-active substances in the surface requires time if the molecules in question are large. While molecules of the order of size of alcohol obtain the maximum concentration in the surface within l/50th of a second, protein molecules need several minutes. During this period the surface tension decreases gradually until the maximum accumulation of the most surface-active molecules or particles is reached.

Whilst pure water has the surface tension of 73 dynes per cm., a 1 per cent, soap solution has a surface tension of only 25 dynes per cm. This means that the soap molecules accumulate densely in the surface, forming, so to speak, a film of soap. In a solution of saponin—an extract from Quillaja saponaria, which is often used as a detergent instead of soap—the surface tension is also low. In such solutions a surface film is formed which is almost rigid. The existence of surface skin becomes obvious if the air be sucked out of a saponin bubble, the bubble will shrink like an empty bag. It is evident that when such surface films are formed the stability of the foam will depend on the rigidity of the film. In general, it may be assumed that if the molecules or particles are long and with side-chains, they will cling together, thus stabilising the film. The same effect may result from electrical charges of particles or molecules. In the case of an aqueous solution of alcohol the surface-active molecules have neither of these properties, and the life of the foam is very short. A pure liquid contains only one type of molecule; no accumulation in the surface will occur and no foam can be formed.

Soap and saponin solutions form stable froths, and both substances are surface active. They consist of long molecules or particles which are so largo that they form a colloidal solution. Furthermore, soap and saponin molecules have a polar construction. In soap the carboxyl group has a powerful affinity for water, whereas the hydrocarbon chain is hydrophobic. Therefore, on the surface of a soap solution the fatty acid molecules have a distinct orientation. They immerse their carboxyl group into the water, putting their long hydrocarbon tail into the air—in other words, they are standing like ducklings on a pond.

Another property of the liquid which increases the stability of the foam is a high viscosity. In a foam formed on such a liquid, the liquid in the film will drain off more slowly the higher the viscosity, thereby adding to the strength of the films. A high viscosity alone, however, is not sufficient to form a stable froth.

Just as the properties of the liquid are of the utmost importance to the stability of the foam, the properties of the gas contained in the bubbles, as well as the size of the bubbles and the pressure of the gas in the bubble, are of great significance to the stability.

According to Bechold and Einstein, the following relation exists between the pressure p, the surface tension at, and the diameter D, of a bubble in a liquid:

If the surface tension is constant the pressure in a bubble will be inversely proportional to the diameter: the smaller the bubble the greater the pressure. This may be shown by connecting two soap bubbles of different size with a tube: the gas is pressed from the small to the large bubble.

If, on the other hand, the size of the bubble is kept constant, the pressure in the bubble is proportional to the surface tension of the liquid. Thus, Lord Raleigh showed that if two equal bubbles—one of soap and one of saponin solution—were blown on two tubes and the tubes were connected, the saponin bubble contracted and blew air into the soap bubble. This result was to be expected from the fact that the surface tension of the soap solution is considerably less than that of a saponin solution of equal concentration. One of the quickest methods of measuring the surface tension is based on the same principle: From a capillary tube immersed in a liquid, air is bubbled until the pressure has diminished so much that new bubbles cannot be formed. On determining this pressure in pure water, and then in the liquid of which the surface tension is to be determined, the unknown surface tension is easily calculated. With the Cassel apparatus which is used at the Tuborg breweries, the formation of bubbles in water stops at about 15 cm. water pressure, whereas in beer the limiting pressure is about 10 cm. The surface tension of water being of72 dynes per cm., the surface tension of beer, according to the above relation, will be:

If the pressure is kept constant the size of the bubbles will be proportional to the surface tension. Very small bubbles may be formed on forcing air through a Chamberland filter immersed in a liquid. Bubbles thus formed in water are much larger than in an aqueous solution of alcohol, where they are so small that the liquid seems to be turbid.

And then as to the properties of the gas itself. Boys, in his well-known book on soap bubbles, describes an interesting experiment: If a soap bubble blown on a tube be kept for some moments in a glass containing the vapour of ether, the air which the bubble will press out from the mouth of the tube will be able to burn with a flame several inches long. In the short period during which the bubble was kept in the ether vapour large quantities of ether had passed into the bubble through the film. In the same way a gas in a bubble may diffuse through the film to the surrounding atmosphere; this will happen if the pressure of the gas in question is less outside than inside. This diffusion—which is of great importance to the stability of a foam— depends on two other properties of the gas, namely, the size of the molecules and the solubility of the gas in the liquid. The smaller the molecules, and the higher the solubility, the greater will be the diffusion velocity.

We may summarise the significance of the various properties of liquid and gas, and the laws governing the equilibrium of a bubble, by considering the formation and collapse of a foam.

Let us suppose that bubbles of various sizes are formed in the interior of the liquid: the bubbles will ascend—the larger ones quickly, the smaller ones slowly, and the smallest very slowly. During the passage through the liquid on their way to the surface the bubbles will accumulate a film of the surface-active substances in their surface. The big bubbles will have very little time for this accumulation, which, in case of a surface-active colloid, may not attain maximal concentration. The smaller bubbles, which stay for a long period in the liquid, will probably have sufficient time to accumulate a layer of the surface-active substance in maximal concentration. In the smallest bubbles there may even be time for the selection of the most surface-active particles, which will gradually expel less surface-active substances from the surface. Turning to the collapse of the bubble, it will be remembered that the pressure of the gas is greater in a small than in a large bubble. The consequence will be that the gas in the small bubbles will diffuse into the larger ones, the smallest bubbles gradually disappearing. Foam consisting of small bubbles will be more stable than foam consisting of large bubbles. As already mentioned, the surface film of a small bubble is more compact and coherent than that of a largo bubble, and apart from other considerations, this fact accounts for a greater stability. Furthermore, the liquid which has been carried into the foam with the bubbles will drain off more slowly in a fine foam than in a coarse one. With a given volume of gas the amount of liquid between the bubbles will be almost independent of the size of the bubbles, but in the case of small bubbles the number of narrow passages for the liquid will be greater, and according to Poisenille’s law, the quantity of liquid flowing through a capillary is proportional to the fourth power of the distance between the walls of the capillary. Therefore, the many capillaries of a fine foam retard the draining off of the liquid. For the same reason it will be understood that the viscosity of the liquid plays an important part in the stability of the foam.

Foam on Beer

In discussing foam on beer, it is necessary to distinguish between the properties of head formation and head-retention. Head-formation may be measured by the quantity of foam formed on pouring out the beer under standardised conditions. Any head-formation is dependent upon some capacity to retain the head, and as is well-known, that capacity is always present in beer, though in varying degrees. On closer examination the liquid part of the beer proves to possess just the properties necessary for foam retention, which has been discussed in the preceding section.

Lüers, Geys and Baumann have shown that the surface-active molecules and colloidal particles contained in beer, such as volatile acids, esters, proteins and hop resins, all follow Gibbs and Thomson’s rule (loc. cit.). They are accumulated in the foam formed on beer, though in the beer itself they are present only in small quantities. That is evident from the taste of the foam, which is extremely bitter owing to the high concentration of hop resins. Dextrins do not accumulate in the foam. This we proved by the following experiment. By means of a Chamberland filter, 5 litres of foam were formed from 1 litre of beer, and then the foam separated from the beer. This operation was repeated six times with the same portion of beer, after which the residual beer and the beer formed from the collapsed foams were analysed. We found that the two fractions did not show any difference as regards extract contents, reducing sugars, and reducing sugars after acid hydrolysis. The foam beer had a considerably lower surface tension than the residual beer; this is a direct proof of the accumulation of surface-active substances in the foam. During the experiment it was noted that the foam formed the first time was more stable than that formed last, a result to be expected as the substances which stabilise the foam are gradually removed.

If the experiment be carried out without removing the foam between the different formations, letting the foam collapse between every two operations, then the head-retention will again decrease. Simultaneously the beer becomes turbid. It would seem natural to explain the falling head-retention by coagulation of the stabilising substances. It is easy to imagine how the large molecules of protein and hop resins will cling together when brought into close contact in the

surface of the bubbles. It is also easy to understand how this ability is lost when the particles or molecules have once participated in this agglomeration. These more or less colloidal particles are easily removed or destroyed. Thus, Petit was able to reduce the head-retention very considerably by ultra-centrifuging beer, whilst addition of proteolytic enzymes to beer decreases the head-retention because the large protein molecules are broken down to smaller ones.

The surface-active substances in beer are: alcohol, small quantities of volatile acids and esters, besides colloidally dissolved proteins and hop resins. Owing to these substances the surface tension of beer is low, varying from 44 to 50 dynes, and accordingly, bubbles formed in beer will have a smaller diameter than bubbles formed under similar circumstances in water.

Lüers has calculated that 100 c.c. of carbon dioxide, liberated by pouring 1 litre of beer into a glass, will form three millions of foam bubbles with a diameter of 0·4 mm. and a surface of 1·5 sq. m. This surface is 144 times greater than the surface of one single spherical bubble of 100 c.c.

The best head-retention is obtained when the most surface-active substances are those of which the molecules or particles have the greatest tendency to cling together—or properly expressed — to coagulate when Drought into contact, be it owing to the size of the molecules or to electrical charges. This, however, is not easy to realise; in fact, the opposite is seen very frequently, for instance, when beer is poured into greasy glasses. The fat or remnants of soap have great surface activity, and will expel the proteins from the surface films. At the low pH of beer, soap will have no foam-promoting properties, because it is hydrolysed to free fatty acids, with the result that the foam collapses.

As regards the third property of importance to foam-retention, the viscosity of beer is considerably higher than that of water, varying within wide limits according to the gravity of the beer. For heavy types, such as stout, the viscosity may amount to three times the value of water.

Thus, it is seen that the liquid phase of normal beer has all the three properties necessary for the formation of a stable foam: it contains easily-coagulable colloidal particles, it has a low surface tension and a high viscosity.

As to the gas contained in beer and forming the foam, it has been found that a foam on beer made by nitrogen is four times as stable as foam formed with carbon dioxide. That cannot be caused by chemical reactions, since both nitrogen and carbon dioxide, under the conditions, are almost inert gases. Neither can it be caused by the influence of the carbon dioxide on the acidity of the beer—we have found almost the same relation at pH 2 and at pH 8. The probable explanation is that carbon dioxide passes through the foam films more quickly than nitrogen. But nitrogen and carbon dioxide having almost the same diffusion velocity, the solubility must be the deciding factor. The gas cannot pass the film unless it is dissolved in the liquid, and in this respect the two gases behave very differently, the carbon dioxide having a solubility in water which is about 55 times greater than that of nitrogen.

Methods of Determination

If these theoretical considerations are to be of any value to the practical brewer, it is necessary to be able to test the effects, as regards the head-retention, of all the possible changes in the making of malt and brewing of beer. Many attempts have been made to measure the head-retaining capacity of beer, but all have failed owing to the difficulty of measuring the volume of the foam. Furthermore, a clear distinction has not been drawn between head-formation and head-retention. The lack of suitable methods for measuring the two properties is undoubtedly the main reason for the present poor knowledge of foam, and also for the many different views, often contradictory, on the problems connected with foam on beer. In working out our method for measuring the foam-formation, we started from the following considerations: — Foam-formation depends on the manner in which the beer is poured out, on the temperature of the beer, and—above all— on the carbon dioxide-content of the beer— or to be more correct—on the difference between the real carbon dioxide-content and the content in equilibrium with one atmosphere of carbon dioxide. Theoretically, the head-formation ought to be determined by pouring out instantaneously and immediately

measuring the quantity of foam. These operations take some time, and thus the amount of head formed will depend also on the head-retention. The only way out is to reduce the time of the various operations as much as possible. Another difficulty is that the natural equilibrium of the beer must not be disturbed before measurement; therefore, the analysis cannot be made with a fixed quantity of beer, and the casual bottle has to be used as a unit. But the mouths of various bottles will vary in diameter, so that a uniform pour from the bottle is impossible. For that reason we have constructed a siphon, through which the bottles can be emptied in exactly the same way from analysis to analysis. Our procedure is as follows: The beer is run into a cylindrical separating funnel, by means of which it is possible to separate sharply the foam from the beer at a given moment by letting out the beer under the foam. After this separation there is ample time to determine the quantity of foam which existed at the moment of separation, as the foam is weighed instead of its volume being measured.

We define the head-formation capacity of beer as the quantity of foam present 30 seconds after pouring the beer out of the bottle under standard conditions. As shown by Holm and Richardt in a series of experiments (this Journ., 1936, 191), the head formation is proportional to the carbon dioxide-content. From this it follows that a determination of the head-forming capacity is just as well done by estimation of the carbon dioxide-content of the beer, and, in fact, in the Tuborg Laboratories this latter determination has almost completely re placed the estimation of the foam-forming capacity.

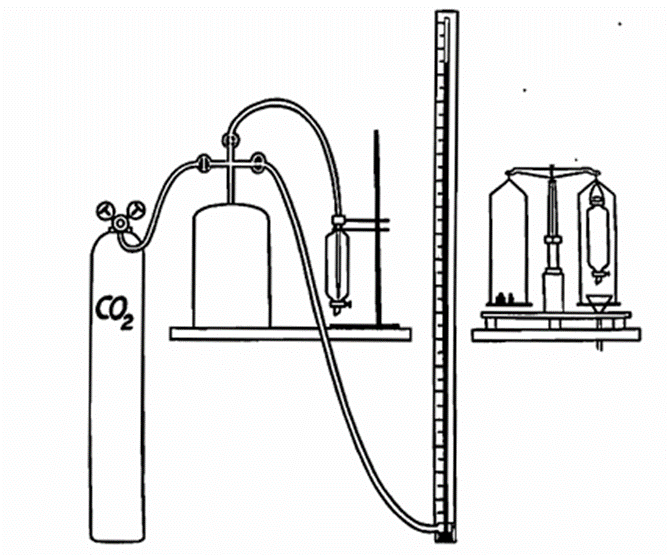

The method of determination of head retention capacity worked out by us is based on the following principle: At a given temperature a certain volume of foam is formed from a known volume of beer by blowing carbon dioxide of constant pressure through a Chamberland filter. At determined intervals the residual foam is weighed in the manner described. The temperature being of great importance, the beer is stood for several hours in a water thermostat at 68° F. (20° C), and the measurements are carried out in a room where the temperature is automatically regulated to the same degree. These precautions are necessary for exact determination; for less exact purposes a constant room temperature may be dispensed with. The carbon dioxide pressure is easily kept constant at 175 cm. of mercury by means of a container with a volume of 25 litres.

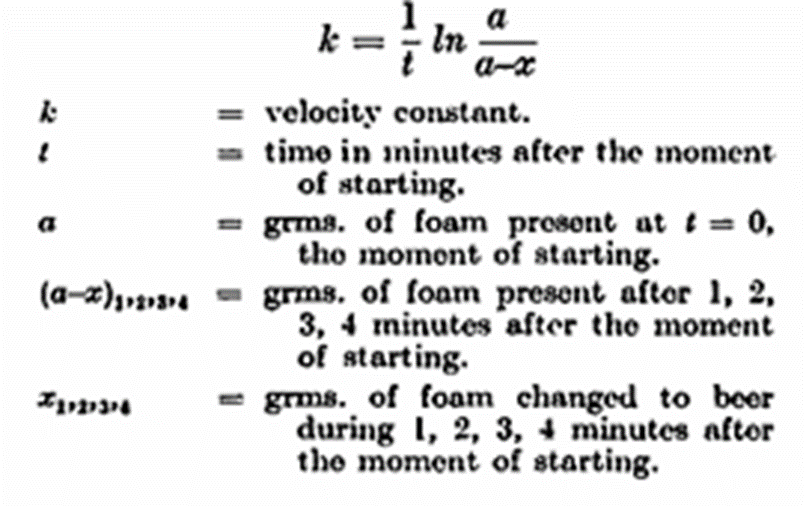

To determine the head-retention capacity 200 gm. of beer are weighed into the separating funnel. The foam is formed by blowing carbon dioxide through a Chamberland filter immersed in the beer. The funnel is suspended from a specially adapted balance; the beer is separated from the foam, at the same moment a stop-watch is started and the weight of the foam is determined to l/10th gm. At intervals of exactly one minute the accumulated beer is run off and the funnel again weighed. Five such determinations may be made before the foam has collapsed to about 10 gm. By means of this method it has been found that at any moment the velocity of foam collapsing is proportional to the amount of foam present at that moment. This is analogous to a well-known phenomenon in physical chemistry; the so-called reaction of the first order, that is, a reaction in which a single substance undergoes change. The velocity of such a reaction is easily calculated from the following formula: —

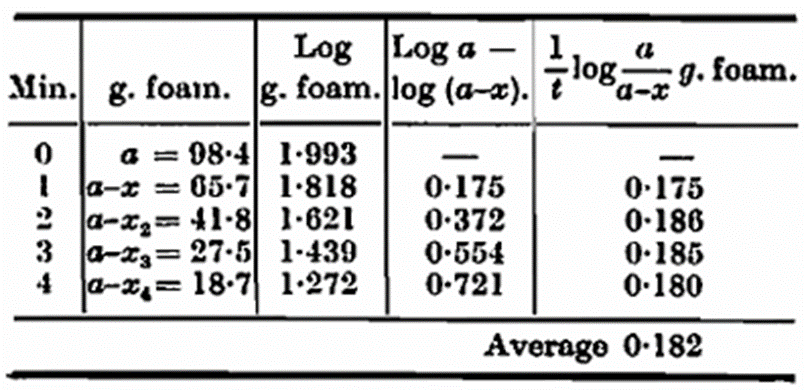

The following is an example of the calculation involved, Briggs’, instead of natural logarithms, being used: —

The logarithms of the weights vary linearly with the time, and k is calculated by dividing the differences of the logarithms by t. The calculated value of k normally shows a variation of ± 5 in the third decimal figure, the first value being the higher, the latter somewhat lower. One thousand times k is called the foam figure; this figure is inversely proportional to the stability of the foam. To obtain direct proportionality Helm and

more convenient to express the stability by the time required for one half of the amount of foam present at any moment to change to beer. This time is known as the period of half-change, and is found by replacing x by a/2 and calculating t by means of the found value of k. If the resulting t be multiplied by 60, the half-change time ht is expressed in seconds. The calculation is very simple, as shown by the example:

These methods of determination and calculation have advantages: the stability is indicated by only one figure, the half change time; the figure is directly proportional to the stability; the result is an average of several measurements; the determinations are very exact compared with those of other methods, weights instead of volume measurements being recorded. With in the same laboratory duplicate determinations do not vary more than ± 1 per cent., and with control determinations in different laboratories the variations were not much greater. Since the foam is formed artificially, the method may be applied generally. This may be of interest in the examination of samples of wort from the copper, or of beer from the fermentation vessel or storage cellar.

On comparing our results with those in practice we have found that beer with a half-change time of more than 90 seconds has an excellent head-retention, while beer with a half-change time of less than 80 seconds has a poor head-retention. In a sample of Norwegian bock beer we found a half-change time of no less than 140 seconds, and in a sample of a French export beer, stored for a long time, the half-change time was not more than 70 seconds.

Influence of Variations in Malting and Brewing

By means of the methods just described wo have endeavoured to examine the influence of various factors in the malting and brewing process on the head-retention capacity of beer. The results are only of a preliminary character, and whilst definite conclusions can hardly be drawn, some of the observations may be of interest. In the experiments only one factor was changed at a time; the resulting half-change time was an average of several determinations.

Influence of Variety of Barley. —Two Danish varieties—Abed Kenia and Abed Binder, of the 1933 crop, were examined. The two lots were grown on the same farm, and were treated uniformly throughout. In spite of the fact that Binder is regarded as a much better malting barley than Kenia, no difference in respect of head-retention was found in the finished beer.

The effect of drying barley was examined with Abed Maja, 1934 crop. Two lots from the same part of the country were uniformly treated, except that one lot was dried at 122° F. until the moisture-content was 10·5 per cent., whereas the other was malted directly with a moisture-content of 16·3 per cent. The result was that the dried barley yielded a beer with a little better head-retention than the undried barley.

The influence of protein-content of the barley has only been superficially examined. The beer from Kenia barley, with 2·1 per cent, nitrogen, had a better head-retention than beer from Binder barley of the same crop, but with a nitrogen-content of 1·6 per cent.

The influence of temperature during flooring was examined in one large parcel of dried Binder barley, harvested in 1932. The barley was malted in Saladin boxes, one part at a temperature of 57-61° F., another at 61-64° F., and a third at 64-68° F. A better head-retention was found in the beer from barley malted at 61-64° F., whereas in the beers from cold and warm malted barley the head-retention was found to be the same.

Helm and Richardt (loc. cit.) have also examined the influence of variations during malting and kilning on the head-retention of the beer with our method. The malting experiments were carried out with Binder barley from the 1933 crop. Half of the barley was allowed to grow long, the other half short. Each of the different growths was divided into two halves, one of which was cured at 167° F., the other at 200° F. They recorded that the short-grown malt yielded a beer showing a slightly better foam stability than the long-grown malt. The drying temperature gave a pronounced difference, the foam stability being distinctly better in beer produced from highly dried malt than in beer from malt dried at a low temperature, and this was found with both over- and under-modified malt. These results accord with own experiments. We found that the head-retention capacity of the beer from Pilsen malt kilned in the normal way was much better than that of beer from a very low-kilned special malt. The action of the higher temperature must undoubtedly be due to a partial destruction of malt enzymes, the action of which during mashing is thus much reduced.

We also find that addition of raw grain to the grist reduces the head-retention of the beer. In a gyle where 20 per cent, of the malt was replaced by rice, the head retention was distinctly poorer than in a gyle brewed from malt alone.

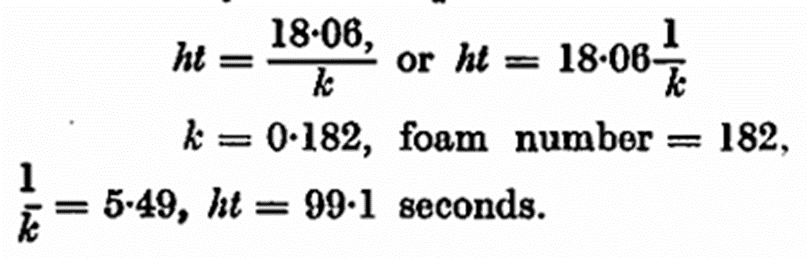

By varying the mashing method, it was found that the two-mash method resulted in a beer with better head-retention than the three-mash method. In the three-mash method the goods are kept for about half an hour at 126° F., a temperature at which the proteolytic enzymes are particularly active. This temperature is quickly passed in the two-mash method (see Table A).

In examining the influence of the variety of hop, Saaz hops, 1930 and 1932, and Hallertau, 1931, were used. When the hop rate was kept constant, the two latter lots gave beer with a better head-retention than beer brewed with the 1930 Saaz hops. The quantities of bitter resins kept constant gave the same result; hops from the last two crops were decidedly the best. This indicates that the change which the bitter resins undergo during storage is a factor of importance (see Table B).

Regarding head-retention during fermentation, we have always found that this increases, until an optimum is reached after about four weeks, when it again slowly decreases. This is in agreement with results lately published by Abramov (Böhm. Bierbauer, 1936, 63, 371), and with practical experience in general (see Table C).

Filtration through ordinary beer filters reduces head-retention, and we have not been able to find any case of improvement, such as maintained by Krauss (Woch. Brau., 1932, 408; also this Journ., 1933, 130). Our results confirm those of Helm and Richardt (loc. cit.), and Abramov (loc. cit.). Ordinary filtration, followed by passage through a Seitz filter, reduces the head-retention still further. That the filter removes substances which promote head-retention is suggested by the vigorous frothing of the first wash water from the pulp.

The influence of bottling on head-retention has been examined by Helm and Richardt. In normal bottling, i.e., filling bottles containing air, we also find that the head retention is considerably better than when bottles containing carbon dioxide are filled. Beer bottled in a specially designed machine fitted with a carbon dioxide filler showed a distinctly poorer head-retention than normally bottled beer. If the air contained in the neck of the bottle is expelled for instance by frothing of the beer, the head retention is found to be the same as in bottles containing carbon dioxide. The best head-retention is obtained if the bottles are first filled with nitrogen (see Tables D and E).

Pasteurisation reduces the head-retention, and the effect is greater the higher the temperature and the longer the time of heating.

On storing the beer at 90° F., we found a distinct decrease in head-retention in pasteurised beer. The explanation given oy Helm and Richardt, that the decrease is due to the consumption of oxygen by the yeast, is no doubt correct, but a further probable factor is the slow degradation of proteins. According to the same authors the head-retention is increased both in pasteurised and unpasteurised beer on keeping at 32° F. and 50° F. At 68° F. there was no definite alteration. Our investigations with beer stored at 60° F. gave the same result. In pasteurised beer stored at room temperature we have found that the head-retention is reduced slightly during the first days, after which it remains constant.

Besides the bearing of malting and brewing conditions, we have examined the effects of additions to the beer. Thus, if water is added, the head-retention distinctly decreases, which is contrary to the findings of Krauss (loc. cit.).

While Lüers and Moninger (this Journ.,1936, 90), found that small quantities of neutral salts have a favourable influence on head retention, we find that small quantities of sodium chloride and sodium sulphate, when added to beer, have no effect, or cause a slight decrease. Zinc, copper, ferrous and ferric salts, on the other hand, improve the head-retention. These salts contain ions which may become present in the beer from various materials in the brewery, and the action must be due to a chemical reaction between the ions and some of the foam promoting substances, probably proteins. Thus, ions of iron are very stable in beer, and their presence can only be proved after treatment with concentrated hydrochloric acid. Iron salts cause a distinct change in flavour. The bitterness of the hop resins is reduced, and with large quantities a disagreeable metallic flavour develops. The beer becomes turbid, the foam is greasy and stable, and has a yellowish or brown colour. We have found that ferrous ions have a more intense action than ferric ions; even 1 mg. of ferrous ions in a litre of beer causes a noticeable improvement in head-retention. The ratio of the action of zinc, copper, ferric and ferro ions is 1:2:10:20.

Head-retention is also dependent on the acidity of the beer, the stability of the foam decreasing on addition of both bases and acids. This optimum indicates a relation between head-retention and amphoteric com pounds, probably proteins. The leucosin of barley, the albumin and the zymocasein of yeast, are proteins of which the isoelectric point is at the pH of lager beer, viz., about 4·5, where head-retention has its optimum. This is confirmation that amphoteric compounds have a maximal tendency to coagulate and a maximal tendency to be absorbed at the isoelectric point.

The addition of ethyl and amyl alcohol reduces the head-retention of beer. In similar concentrations the action of amyl alcohol is about 20 times as strong as that of ethyl alcohol, and if beer of high gravity now and then has a poorer head-retention than low-gravity beer, the reason is probably the high concentration of alcohol and esters,

We can also confirm the results of Helm and Richardt regarding the action of enzymes such as pepsin and papain. These and other proteinases which we have examined all have a harmful effect on head-retention. The same is found on the addition of a-amylases to beer; the viscosity and the stability of the foam is lowered. The action is due to the degradation of dextrine of high molecular weight present in the beer. β-Amylases, on the contrary, neither influence the viscosity nor the head-retention of beer.

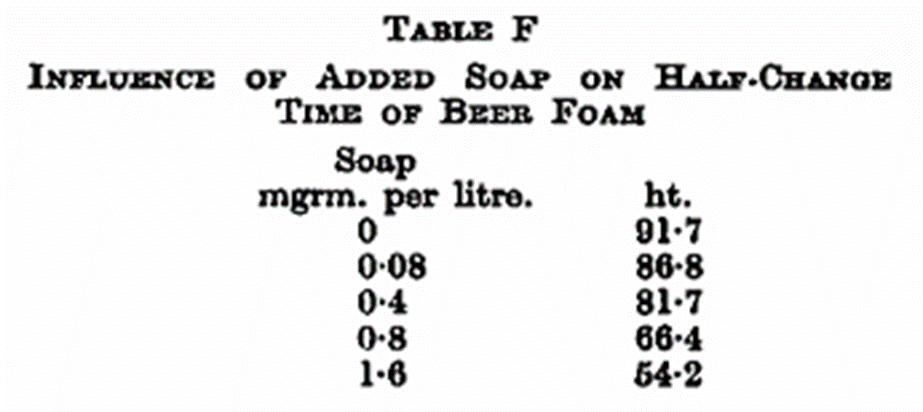

Fats and soap, even in very small quantities, greatly reduce head-retention. The action of soap is about 10 times as strong as that of fat; 1 mg. of soap added to 1 litre of beer causes a reduction of the half-change time from 92 to 62 seconds. This action is, of course, well-known, and it shows how dangerous it is to clean beer glasses in soapy water (see Table F).

I am fully aware that our investigations briefly recorded in this paper cover only a small part of the long route from barley to beer, and probably many of the results need confirmation. However, there are a few points which are in such good agreement with general experience that they may be regarded as correct. It may be convenient to summarise these: —

(1) The temperature on the malt kiln should be kept as high as possible, due regard, of course, being given to the colour of the malt.

(2) The mashing (decoction) should be finished as quickly as possible.

(3) The hops should be fresh and rich in soft resins.

(4) If the beer undergoes a secondary fermentation this should be effected with as little yeast as possible.

(5) After 4-6 weeks storage the beer has its optimal head-retention.

(6) Unnecessary frothing of the beer in tubes and vessels should be avoided.

(7) The filtration should not be too perfect.

(8) The pasteurisation process should be as brief and the temperature as low as possible.

(9) On pouring out the beer care should be taken to get as much air incorporated with the foam as possible.

(10) The service glasses used must be clean, and contain no traces of fat or soap.

Tuborg Brewery, Copenhagen.

Discussion

The Chairman congratulated Dr. Blom on having read one of the most interesting papers ever presented to the Section. Not only had he described laboratory methods for carrying out the tests, but had followed the matter up with practical tests, and had also given them warnings for their guidance. Dr. Blom had chosen a subject which would give most people occasion for a great deal of thought.

Dr. L. R. Bishop said he was in Copenhagen last summer, when he had the pleasure of visiting Dr. Blom’s laboratory, and had seen the careful way in which the experiments were carried out. He was able to appreciate how important were his results from the brewing standpoint. His work emphasised the fact that the complex proteins and other materials responsible for head-retention were the same as those causing haze; and that it was not possible to draw a clear distinction between the proteins and other bodies causing haze and foam-formation.

Prof. R. H. Hopkins said that Dr. Blom had treated the subject in a very systematic and logical way. He started with the nature of foam, and related it to the type of foam with which they were most familiar, namely soap, discussing the properties of the liquid and then of the gas-content. They were shown Boys’ interesting experiment in which ether passed through the enclosing envelope, a fact which was demonstrated by the emerging gas being combustible. Dr. Blom had applied the idea to beer foam and found, as might have been expected, that nitrogen gave a more permanent foam than oxygen, and oxygen, in turn, a more permanent foam than carbon dioxide. This might not be of great practical value, but it was interesting in that it showed that there was a new function of “nitrogen” in beer! It gave better head-retention.

When the small bubbles of gas were rising through the beer the surface-active colloids collected on the surfaces, and the smaller the bubbles the greater was the tendency for the colloids to collect. It seemed to him, therefore, that taking that in conjunction with the fact that surface-active colloids tended to coagulate in the foam, if a brewer were to carbonate beer using a very fine spray of gas, there would be a tendency to bring about the collection of surface-active colloids on the surface of the bubbles, and it was possible, coagulation and loss of head-retention power. He would like to know whether Dr. Blom had any views on the point. He would also like to know whether it was possible to perform experiments on those lines with the Chamber land filter. He wished to ask, further, over what range of carbon dioxide concentration head-formation was proportional to or increased with the carbon dioxide-content. He believed it was over only a limited range. Reference had been made to two-mash and three-mash decoction processes, and as these varied, he would like further information regarding temperatures and rest periods. It would also be useful to know whether Dr. Blom had ever attempted to relate the fat-content of barley or malt with the head retention of beer. The fat-content of barley was appreciable but usually overlooked, although brewers went to some trouble to avoid fat in maize when used for brewing.

Mr. R. H. Evans, in referring to the temperature at which malt was cured, asked what the higher temperature was at which the malt was cured. If a temperature of 215° F. had been reached, would it have resulted in a decrease of head-retention. Further, with slight caramelisation, would there be a decrease of head-retention.

Mr. J. H. St. Johnston said that he had noticed in the case of two malts of identical growth on the floor, but one having been kilned at a higher temperature than the other, the malt kilned at the higher temperature had a lower surface tension and gave a better head when brewed. Many brewers, he thought, had noticed that when caramel was added to beer head-retention was definitely improved.

Mr. B. M. Brown described the paper as outstanding in quality, it added considerably to their knowledge and to the means at their disposal for tackling the problem of foam. He was glad that Dr. Blom had insisted on the necessity for distinguishing between head-formation and head-retention, as there was a tendency to confuse the phenomena, and they must be treated distinctly. Dr. Blom had pointed out that the percentage of C02 in beer might be taken as the measure of head-formation. A point not mentioned, however, was that a brilliant beer, containing 0·45 or 0·5 per cent, of carbon dioxide, could be poured out in such a way that there was no head formation. The same beer, containing a haze or a little sediment, or poured into a glass which was not clean could give a large head. That was a fact to be taken into account in the measuring of head formation. Turning to head-retention, Dr. Blom’s figures appeared to vary between 80 and 90. That was not a large range. He would like to know whether in the ordinary course of browning Dr. Blom had found any appreciable difference from day to day. With regard to the effect of filtration, could Dr. Blom give any figures showing the reduction of head-retention as the result of filtration? It seemed to him (the speaker) that the loss on the filter might completely dominate possible variations in beer as brewed.

Mr. A. Clark Doull said that it was of interest to note that in 1936 Dr. Blom had stated that no direct relation could be proved between head-retention and surface tension. Among foam investigators there appeared to be a consensus of opinion that protein bodies, such as peptones and albumoses, were essential to head-retention, and as these bodies were said substantially to lower the surface tension, he had wondered whether Dr. Blom still held to the view that those proteins were necessary for good foam formation. It was obvious, however, from what Dr. Blom had said in his paper, that he did consider the presence of these protein bodies as essential, despite the fact that there was apparently no definite relationship which could be proved between head retention and surface tension.

He was interested in what Dr. Blom had to say with regard to bubbles of CO2 in the beer, and the fact that when the bubbles were of large diameter as against bubbles of very small diameter there was a distinct difference in the head-retention. That was a phenomenon that he (the speaker) had observed, particularly in the case of beers which were naturally conditioned in bottle. If the conditioning was carried to, say, 2,500 to 3,000 c.c. of gas per litre—a very high degree carbonation—which resulted in a very vigorous sparkle, the gas came up from the bottom of the glass in a very active spiral. Under such circumstances and where the gas bubbles were very small, a tenacious head was produced. When, however, the gas bubbles were much larger, he (the speaker) had observed that the head retention was definitely poor. He did not know whether Dr. Blom could give any idea as to the explanation of the difference in the size of the gas bubbles in one bottle as against another. He should like to know if, in the case of the beer with the large gas bubbles, the breaking up of the head was due to the physical action of the large bubbles, or if the explanation lay in the absence of head-forming proteins and hop soft resins in the beer, and if that was so, was there any relationship between the absence of head-forming material and the production, during the fermentation in bottle, of large gas bubbles; was the size of the gas bubbles to be regarded as a purely fortuitous circumstance?

Dr. Blom, in reply, said that with increasing concentration of carbon dioxide more colloids were carried to the surface, causing more foam, and in that way the carbon dioxide-content played an important role. As to temperature and resting periods in two-mash and three-mash decoction methods, in general, with two-mash, they began at 104°F., rose to 140-149°F. and then to 167-176° F. With the three-mash method they put in a “rest” at 126° F., i.e., the temperature at which the protein decomposing enzymes were very active. He had not investigated the question of the fat content of barley and malt. Certainly, if they used large amounts of maize or rice they would introduce fat without introducing colloids.

He had no direct experience on the point raised by Mr. Evans. The beer called porter in Denmark, that was a beer made with coloured malt, showed better head-retention than normal dark beer. As to how far the superior head-retention was due to the higher curing temperature and to the fact that such beer contained more extract, he could not give a definite answer.

The relationship between head-retention and surface tension was very obscure, in addition to which the exact measurement of surface tension was extremely difficult. If the surface tension of normal beer was reduced from about 47 to 39 by adding amyl alcohol, a point would gradually be reached when the foam would be unstable. Under such conditions the amyl alcohol became the most surface-active substance, and displaced the proteins from the surface of the bubbles.

He agreed that it was possible to pour out beer without forming much foam. It was therefore desirable to construct a syphon so that the beer was always poured out in the same way. Another factor, however, entered into the question of head-formation, and that was the velocity with which the carbon dioxide was liberated. Personally he had not touched that question, but Helm had found a distinct relationship between head-formation and carbon dioxide-content. It should be remembered that if they wished to measure head-formation the bottles of beer should be kept for some hours at a uniform temperature. If the beer was cold they did not get so much head; if it was warm they got too much. But the results in his tables did not refer to head-formation but to head-retention. As to nitration, it would be noticed that in the case of the beer first passed through, more colloids were removed than later on. The same remark applied to colour. More of the colour substances were removed from the first beer filtered. There was always a decrease in head-retention, but only one or two points—from 100 to 98, for example. There was a distinct difference between the head retention in summer and winter. In winter and spring the head-retention was much lower than in summer-time, when beer was sold which was five weeks old. It was the storage which made the difference. With regard to the variation in head-retention from brew to brew, they did not measure head-retention in each brew. Measurements had been made with beers obtained from different breweries in Denmark, and in that case they had found differences of 15 per cent.

If a Chamberland filter was used and there was a very high pressure of carbon dioxide, they would get bigger bubbles at high pressure than with a small pressure. If foam from the same sample of beer was made with high pressure and low pressure, there was a distinct, though not great, difference in the half-change time. Larger bubbles were formed in a beer with a carbon dioxide-content of 0·42 per cent, as compared with 0·36 percent. The bubbles rising through the beer were accumulating carbon dioxide and increasing in size, and they increased more in size if the pressure outside was greater. The pressure was greater with a 0·42 per cent, carbon dioxide-content, and therefore the bubbles would be larger.

The Chairman proposed a cordial vote of thanks to the author for his most interesting paper, and presented him with a silver tankard as a memento of his visit.