A Meeting of the American Brewing Institute

Meeting Held at the Chemists’ Club, New York – January 26, 1907

Mr. Louis B Schram in the chair

Notes on English Brewing

By Dr. Max Wallerstein

This paper, which deals with the science and practice of English brewing, is based on observations made during my visit to England last year, at the time the Society of Chemical Industry held its annual meeting in London.

The large number of American members and friends who participated can look back to a very eventful time. It was a highly interesting, entertaining and instructive affair, and with all the dinners, receptions and sight-seeing, the practical side was not neglected, and ample opportunity afforded to visit centers of commerce, and to inspect methods of manufacture.

The brewing industry, which is of enormous proportions, commands a very high position in the United Kingdom.

To give — within the space and time allotted to a lecture – an adequate idea of such an enormous industry, seems to be a hazardous undertaking, and no one knows better than myself the shortcomings of such a purpose. Had it not been my good fortune to receive the valuable assistance of many scientists and practical brewers, to whom I am greatly indebted, I should certainly not feel competent to present this paper tonight.

Before all, I wish to thank Mr. W. Waters Butler, of Birmingham, for his assistance and information.

Science of Brewing.

Although England has been backward in many scientific developments and their application, it must be admitted that in the Chemistry of Brewing that country has taken a leading role; in fact one might almost say that English chemists were the pioneers of a rational and scientific and at the same time practical study of the chemistry of the various materials and processes connected with the brewing industry. Such names as O’Sullivan, Horace Brown and Morris are now numbered among the classics, not only in brewing literature, but in that of the wider field of pure and applied chemical research as a whole. The brewing chemists practising in England at the present day may be divided – without wishing to institute any invidious comparisons – into two classes from a practical, if not from a scientific point of view, namely: first, those belonging to the original band of workers who first seriously attacked the scientific study of brewing problems, and, second, the younger school that has arisen, to a great extent as a result of the teaching of the older men. From the works of the younger generation, it is not too much to say that the original pioneers have found worthy successors and exponents, although I by no means wish to imply that those remaining of the older school are no longer active. On the contrary, the continued and valued publications of Horace Brown, to mention one only, show that some of the pioneers are still in the full maturity of their efforts and work.

Among the original band of pioneers who are still alive and actively employed we may mention particularly[m1] the names of Cornelius O’Sullivan, Horace Brown, Heron and Moritz. Of the younger school the names of, among others, Adrian Brown, Chapman, Salamon, Ling, Baker, Schidrowitz, Briant, Sykes, Mattews, Lott, Miller, Thorne, Murphy and James O’Sullivan will be no less familiar to all those interested in Brewing, Chemistry and Technology.

Cornelius O’Sullivan is Chief Chemist and Brewer to Messrs. Bass, of Burton-on-Trent. It was he who re-discovered Maltose as a definite sugar in 1872, and his work on the dextrins formed by the action of diastase and acid respectively, on the cupric reducing powers of the products of starch hydrolysis, and on the phenomena and products of starch hydrolysis generally (chiefly published in the Journal of the Chemical Society for 1872, 1876 and 1879) belongs to history, and taken together may perhaps be regarded as the most important work on the chemistry of starch and starch products from a brewing point of view ever published.

Horace T. Brown, formerly chemist and brewer to Messrs. Worthington, now consulting brewer and director of the Guinness research laboratory at Dublin, is the author of innumerable works bearing on the chemistry of brewing, many of these being of supreme importance and interest. We may mention specially the work published in conjunction with Heron in 1879, concerning the influence of time and temperature on starch conversion (Journal of the Chemical Society), a work on a similar subject with Morris published in 1885, his paper in 1889 with Morris on the various dextrins, etc., his classical research with Morris on the Germination of the Gramineae, and his more recent papers on the relation of cupric reducing power to opticity, and on the constitution of the starch molecule. (All in the Journal of the Chemical Society, 1885-1902). During the past two years a large number of papers on work done under his direction at the Guinness research laboratory have appeared in the Journal of that institution, dealing with a wide range of subjects. It ought to be said that on the researches of O’Sullivan and Horace T. Brown the whole of modern brewing chemistry is founded.

John Heron is an analytical and consulting chemist and brewer. His association in the work with Brown has already been referred to. In addition, he has published a number of papers on brewing and allied subjects, independently. (Journal Soc. Chem. Ind., 1888, etc.)

E. R. Moritz is a consulting and analytical brewers’ chemist and a practical brewer. He is chemist to the Country Brewers’ Society. In association with the late Dr. Morris, he wrote the well-known “Text Book of the Science of Brewing,” which although now somewhat out of date, is a model in many respects of what a scientific text book intended for practical use should be. Mr. Moritz was for many years one of the editors of The Brewing Trade Review, and a founder of the “Laboratory Club,” which later became the now powerful Institute of Brewing. His latest publication of particular scientific interest was a paper on the “Transmitted Tendencies of Brewing Yeasts.” (J. Inst. of Brew., 1903).

Alfred C. Chapman is well known for his numerous works in connection with the chemistry and technology of brewing, as well as on pure chemical subjects. He is an analytical and consulting chemist and also a public analyst. His work on the Essential Oil of Hops is particularly worthy of mention. His works on purely analytical questions are too numerous to be quoted, but taken collectively they show that Mr. Chapman must be regarded as one of the leading authorities on matters pertaining to brewing chemistry and to analytical chemistry generally in England. He has moreover the reputation of being a man whose practical advice on matters of brewing technology is not only worth having, but also worth following. Among his more recent papers I may mention those of The Essential Oil of Hops, and of Wild Yeast Infection. (1903 and 1904, Inst. of Brew. Journal.)

A Gordon Salamon is a consulting and analytical chemist and brewing specialist, who has in addition the reputation of being a sound practical brewer and man of business. He has contributed to technical literature papers on Malt Making (J. F. I. B.) and on Brewing Water (J. Soc. Chem. Ind, 1885)

Arthur R. Ling. The earlier work of Mr. Ling, in association with Mr. Baker, on “The Action of Diastase on Starch” (J. Chem. Soc, 1895), may now be regarded as classical, although both authors are still comparatively young men. Mr. Ling is an analytical and consulting brewers’ chemist, and is rightly regarded as being one of the most able men in the modern school of thought. He is an authority on malt and malting, as well as on chemical methods and various other departments of brewing technology. He is editor of the Journal of the Institute of Brewing. Among Mr. Ling’s chief works may be mentioned (in addition to that already referred to):

“The Ready Formed Sugars of Malt” (J. F. I. B.), 1898:

“The Determination of the Diastatic Capacity of Malt” (J. F. I. B.), 1896 and 1900;

“Malt Analysis” (J. F. I. B.), 1902 and 1904; · and the papers by Ling and Davis in 1902 and 1904 on the action of diastase on starch paste (J. F. I B. and J. Chem. Soc.)

Julian L. Baker is chemist to Messrs. Watney, Combe and Reid (probably the greatest of the English brewery “combines,” representing some sixty million dollars of capital.) For such an onerous and responsible position probably, no better selection could have been made, for Mr. Baker is not only one of the foremost English exponents of brewing chemistry, but also a man of unbounded energy and practical habit. In him are combined two attributes which are seldom found together, namely, a finely trained and rigidly scientific mind with practical knowledge and action. We have already referred to the classical work carried out by him in conjunction with Mr. Ling, but among his other contributions to science and practice may be mentioned:

“Mannogalactan and Laevulomannan: Two New Polysaccharides” (J. Chem. Soc, 1889).

“The Action of Ungerminated Barley Diastase on Starch” (J. Chem. Soc. 1901).

“Utilization of Waste Yeast in Breweries” (J. Fed. Inst. Brew., 1903). 66 1905)

“The Brewing Industry” (Pub. by Methuen & Co., 1905).

“Observations on the Steeping of Barley” (J. Fed. Inst. Brew. 1905).

Adrian Brown is a Professor of Brewing at the University of Birmingham. He has published much work of scientific and practical interest, particularly that on enzymic action.

Philip Schidrowitz is a consulting and analytical chemist. He has published a number of papers on subjects of interest to the brewer, particularly those in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing, for 1903 and 1904, on the Proteolytic Enzyme of Malt. These may be regarded as pioneer works in this complicated and difficult question. Mr. Schidrowitz is perhaps the leading English expert on the technology and chemistry of Spirits, Distillation and Wine, and his works on the Chemistry of Whisky (Journal Soc. Chem. Industry, 1902 & 1905) represents the first attempts to place the chemical technology of distilled spirits on a scientific basis.

Laurence Briant is another well-known analytical and consulting chemist whose work lies mainly in the domain of brewing technology. His papers in conjunction with Meacham on Hops will no doubt be remembered as being of great importance. He is a thoroughly practical man, and has published many papers on brewing subjects in the various technical journals.

Leonard T. Thorne is chemist to Messrs. Berton, Hill & Co., the greatest brewing sugar manufacturers. He has published numerous papers in connection with the technology and chemistry of brewing sugars and allied subjects.

A J. Murphy is a consulting brewer and chemist whose work has drawn much attention of late years. A very interesting paper of his on the “Germination and Kiln-drying of Barley” appeared in the Journal of the Institute of Brewing, for 1904.

James O’Sullivan is another brewing expert whose name is very familiar in England. He has published numerous papers in connection with the chemistry of starch and brewing, his latest being that on “A Comparison of the Products of Hydrolysis of Potato Starch with those obtained from Cereal Starches.”

In no other country does the brewers chemist enjoy a higher appreciation than in England.

The English brewers recognize that the interests of science and practice are identical, and that the extraordinary development of their industry is due to the indefatigable work of their chemists, to the success with which they attacked the manifold problems before them, and to the skill, energy and resourcefulness with which they have turned the results of their investigations into immediate practical account. The important work which has been accomplished by the eminent scientists referred to, could not have been done without the impetus and liberal aid on the part of the great manufacturing concerns. The classical publications of O’Sullivan, Chief Chemist of Bass’s, and the works of the Guinness Laboratory, will always stand as a striking monument for ideal research work, which is valued not only by the brewing interests, but also by scientific men all over the world.

PRACTICE OF BREWING

Malting

Before the barley is steeped it is usual, particularly with an English grain, but not with Egyptian, Smyrna or American grain, to kiln dry it at a temperature not exceeding 120 ° F. for some 24 hours. It is then placed in a heap or put into sacks to remain for a month or more before steeping, as it is found that by kiln drying, corns that have not been properly ripened in the field, appear to undergo an artificial ripening process. Grain will not grow satisfactorily if steeped immediately after kiln drying, so that a period of rest, not less than one month, is allowed to elapse before steeping. The kiln dried grain, before being placed in the steeping cistern, is carefully screened to remove all foreign matter and half corns from it. The dust is drawn from the surface as the corn passes through the screens by the aid of powerful fans, which deliver the dust into water sprays, where it is converted into mud, and so prevented from being dissipated about the buildings and growing floors, where, of course, it is likely to cause injury to the growing grain.

The steeping water is usually of medium hardness, and is run into the cistern before the grain is added, the temperature being about 55 °F. The grain is run into the water and the light corns float, and are then skimmed off. After about eight hours, the water is run off and a fresh charge of water is added through the bottom of the cistern, and also by the aid of sprinkling pipes above the grain. Several changes of water take place during the period of steeping, which varies from 50 to 75 bours, usually 60 to 65 hours is sufficient. During the period of steeping compressed air is sometimes passed into the grain. This aeration assists in the washing of the grain, and encourages earlier germination when the grain is turned out on the growing floor. Calcium hydrate and sodium chloride are sometimes added to the steeping water, with the object of preventing decomposition. The salt aids in the extraction of husk matter, and also it is found tends to regulate the rate of growth during the germination period.

The Germinating Process.

After the grain is drained at the end of the steeping process it is usually thrown out onto the malting floor, which is made of concrete with a cement surface, or concrete with a semiporous tile on its surface. Here the grain is allowed to be about one foot in thickness, the object being to encourage warmth, and so germination. After about 24 hours this heap, known as the “couch,” is opened out, and the growing barley is spread into a thinner layer, usually being about 4 inches deep. The grain begins to rise in temperature, and to prevent a rapid increase and to encourage growth, is turned by the aid of wooden shovels and hand labor, and is thrown well up into the air so as to thoroughly aerate it. The per- centage of moisture in the grain at this period is about 42%, and varying with the humidity of the atmosphere and the temperature of the grain, moisture decreases, and consequently, to maintain the growth, the grain is sprinkled with water. Germination usually occupies 10 or 11 days, during which time the acrospire has advanced two – thirds to three-quarters up the back of the grain; while the rootlets, 4 to 6 in number, should be about one-third of an inch in length, and of a bushy nature. The slow, cold process of germination is favored, the temperature on the floor not exceeding 65 °F.

The pneumatic systems of malting are not favored, although the drum system is used largely by some distillers. Brewery malsters are under the impression that they have not such good control over the grain in a drum as they have on a floor, and that the “withering” process, which in the floor malting means the thickening up of the grain towards the end of the germinating process, thereby checking the further growth of the grain, and bringing changes about in the body of it, which favor mealiness in the finished malt, cannot be satisfactorily attained in a malting drum.

Kiln Drying of Malt.

The malt when loaded into the kiln has still about 40% of moisture in it, but the grain is not subjected to a higher temperature than 120 °F., until it is comparatively what is known as “hand dry,” after which the temperature is gradually raised during a total period of about 70 hours to 170 °F. to 180 °F. in the case of pale malts; but 180 °F. to 200 °F. for high dried malts. The malt is dried on a perforated earthenware tile or woven wire floor, in both cases a single floor only being used. The double or three floor kilns are but rarely used.

The fuel is usually anthracite coal, but in some cases, coke is also used.

The malt at the end of the drying period generally contains not more than 1 % of moisture, and has a diastatic activity of from 20 ° to 50 ° Lintner, which wide variation is brought about by the temperature used during drying; high temperatures and moisture favoring low diastase values.

English malting methods usually yield a malt which shows 17 % to 20 % of matters soluble in cold water, and soluble matters will be greater where a forced or high temperature germination has taken place, and also in the products produced by roasting the malt at a high temperature. Malts carrying large quantities of these soluble matters are not looked upon with favor.

Black malt which is used in Porter brewing, is produced by roasting malt in a wire cylinder over a fire.

Malt, known as “oak dried malt,” also used in brewing Porter, is produced by drying barley over an oak wood fire.

Crystal malt, which has an excessive sweetness, is produced by roasting malt with more than a normal amount of moisture in it.

Malt is stored in wooden or steel bins, and sometimes in deep brick shafts. Before it is stored, the rootlets are removed by screening machinery, as it is found that the rootlet, if attached to the grain, assists in the absorption of moisture.

Malt is said to be “slack,” and not looked upon as good brewing material, when it contains more than 5 % of moisture; to prevent the absorption of moisture during transit it is filled into double sack.

The greater portion of barley used in English breweries is English Chevalier, but French and German barleys of a Chevalier type, also Egyptian, Cuchac and Smyrna barleys are used. Chevalier and Thin Brewing California and Chilian are also malted, and Montana barleys have been found to produce very good brewing materials. The percentage of foreign grain will vary from 10 % to 50 %, the larger amount being used when English barleys have badly ripened.

Brewing Methods.

Vessels in English breweries are made of copper, iron, wood, or wood lined with copper. The hot water vessels and mash tuns usually being of iron, the boiling vessels, hop-backs and coolers of copper, and the fermenting vessels of oak, pine or cedar woods, or of deal lined with copper.

Grinding of Malt.

It is found that a properly constructed revolving sparger, which distributes the hot water in an even spray, and in proper proportion according to area over the grain in the mash tun, the grain can be ground very fine indeed, without checking the filtration of the wort, and at the same time aids in the yield of a high extract. The extract obtained with good English malt will be equal to 72½ %.

The English brewer usually refers to his malt yielding so many “pounds extract” per quarter, pounds extract meaning that one quarter of malt (336 pounds) would yield 36 gallons of wort, the weight of which would be so many pounds greater than that of an equal bulk of water; 94 pounds extract is equal to about 244.4 pounds of dry cane sugar, which, if dissolved and made up to 36 gallons, would weigh 454 pounds, or 94 pounds greater than 36 gallons of water, and if 336 pounds of malt (or one quarter) had yielded 244.4 pounds of sugar, its extract would be expressed in percentage as 72.7 %.

The crushed malt is usually run into the mash tun through an automatic mixer, wherein sprays of hot water of a temperature of about 165 °F. mix with the crushed grain, forked stirrers thoroughly mixing it before it reaches the mash tun. Such a machine is known as a Steele’s masher- ” Pony Mashers.” Rakes are also fitted into the tun, and are driven by steam power.

The quantity of water used in the mash tun is generally about 2 barrels per quarter of 336 pounds for the first mash, which stands for about 2 hours at a temperature of about 150 ˚F., and when the strong wort is drawn off, the grain is washed out with 4 to 5 barrels of water per quarter, the total quantity of water used, being 6 to 7 barrels, (216 to 252 gallons) per quarter (336 pounds) of malt.

The use of raw grain is not very popular in England, but what are known as “rice grits,” flaked rice and maize, are sometimes used.

Filter presses have also made their appearance in England, wherein the mash is filtered as in a large yeast press, the mash being washed by passing water through it. The press is said to allow the malt to be ground extremely fine, aiding in a greater extract being obtained, and that the time of the operation of mashing is much shortened, but it is doubtful whether the press will come into general use unless a larger apparatus is made, as the present presses are only capable of dealing with comparatively small quantities of malt.

Water.

English brewers are unanimously of the opinion that hard water, which must be organically pure, gives the best results; such waters are used in the production of pale bitter beers, as they prevent the extraction of color and undesirable flavors from the malt and hops.

Great importance is attached to the composition of the water, as experience has shown that waters of some districts are particularly adapted for the production of ales of one particular character, while they are unsuitable for the production of those of another class. It was found that the chemical constitutions of these various waters accounted for the difference in their behavior in brewing operations. So originated the various systems of treating water, which are practiced extensively, and which have been followed with the most advantageous results.

Temperature of the Mash.

Almost exclusively the infusion method is in use. The temperatures for the initial heat vary from about 145-155 °F, and are in accordance with the quality of the malt and the character of the required beers.

Beers intended for storage are mashed at a somewhat higher temperature, to produce a certain amount of slowly fermenting dextrins which provide for the after fermentation during storage. Beers used for quick consumption are mashed at lower temperatures, to produce larger quantities of maltose.

Between these two types there are many intermediate ones that are brewed to suit the particular requirements of different neighborhoods.

There is a method of taking a portion of the strong wort produced by mashing at a low temperature, the mixture being about 130 °F, boiling it and returning to the mash, thus raising the temperature of the mixture to 150 °F, or thereabouts. Such a method is said to increase the extract, and in consequence of the primary low temperature used, a more digested form of nitrogenous matter is produced, and thus assists fermentation.

The residue of the mash, or “grains,” is usually sold for cattle food, either in their wet state or after being dried in drying machines – wet grains realizing about 8 cents per bushel (8 gallons), and dried grains about $17 to $20 per ton.

Additions to the Mash.

It is very rare that English brewers add any chemical, or other substance, to the mash, but if the grain is defective in soundness (as through mold, etc.) or is stained in consequence of badly harvested barley, sulphites such as sodium sulphite are added, the SO2 liberated by the acids of the malt keeping the mash antiseptic during the mashing period. Such substances, however, do not find favor with the majority of English brewers, as fermentations and flavors are not improved thereby.

Mash tuns have a capacity up to 70 quarters (560 bushels), for in larger vessels it is found difficult to manipulate the malt.

The practice of using the last sparge waters for making fresh mashes, although an old English practice, is going out of use, as the disadvantages of using the same, such as keeping them hot and a tendency to retard drainage, far outweigh any little gain of extract which may appear to be attained by the use of them.

Sparge water is of a temperature of 170 °F., so that the worts running from the tun do not exceed in temperature 158 °F., and the runnings show no signs of starch when tested with iodine solution. The final gravity of the last wort is about 1 per cent. of extract.

Boiling of Wort and Addition of Hops.

The wort is generally run direct from the mash tun to the boiling coppers, but in some cases, it is run into what is called “under-back” and is there kept heated until a copper (kettle) or boiling vessel is ready to receive it. The worts are usually boiled for two hours by the aid of direct fire heat, or steam passing through coils, or a steam jacket. Fire boiling still has the preference, although no one seems able to give any good reason why steam, properly applied and at a sufficiently high pressure, is not equal in efficiency to direct fire heat. The fact that direct fire heat gives wort of a darker color seems to be due to the settling of a portion of the hops -on the copper bottom, when charring takes place. The hops are usually added in two portions, the better quality being put in during the last hour or thirty minutes of the boiling period.

Boiling fountains and domes are used to prevent the coppers boiling over, the dome being preferable. Pressure coppers are also used, particularly in the production of stout, but the pressure applied is only a few pounds (3 to 5) to the square inch.

Sugar is sometimes added in the copper or dissolved in a separate vessel and the solution run into either the copper or the hop-back. The sugars generally used are refined cane sugar, cane sugar syrups, glucose made from corn or rice, invert sugar made from cane sugar; also, a sugar made up of a mixture of invert and glucose. English brewers will not, if they know it, have beet root sugar products in the breweries; they are said to favor unsoundness. Caramel or burnt sugar is sometimes added to the wort to bring the various beers up to a definite color standard.

The evaporation in a brewery kettle is from 8 to 10 per cent. of the bulk originally boiled, and the time of boiling does not generally exceed two hours.

Hops.

The hops used are mostly English hops, but in the stronger ales and stouts and in some best pale ales, Continental and American hops are used. The Continental hops are those of the finest quality, Bavarian or Spalt, while the American are those of California growth, comparatively few New York State hops being employed.

Cold storage of hops is now largely practiced in England, the temperature of the rooms being about 30º F.

Hops are seldom used older than three years.

The quantity of hops would average about 2 pounds per barrel, but in the higher-class pale ales 3 pounds per barrel would be a more normal figure.

Saving of Hops.

No attempt is made by machinery to break up the hops, but before they are added to the coppers the larger lumps are broken by hand into smaller pieces.

Additions in the Kettle.

No additions, other than sugar and hops, take place.

The quantity of sugar used in brewing would rarely exceed 25 per cent. of the extract yielding materials; an average figure would be nearer 10 per cent.

The wort, after boiling, is run into a hop-back, a vessel similar in design to a mash tun. From it the wort is run into an open cooler, usually of wood, but more modern ones are constructed of copper or iron, which are situated at the top of the brewery buildings, the depth of wort in such coolers varying from a few inches to several feet. The hops which remain behind in the hop-back are generally washed out by sparging hot water over them, the runnings being pumped up into the wort in the cooler. In some of the old breweries, and in those breweries where the greater portion of the output is strong beers, the hops instead of being washed out are put into a press and the wort extracted from them by hand or power pressure. Such pressure, however, is considered to produce an extract of an intense and unpleasant bitterness.

Used or spent hops are not of any commercial value, but within the past few years they have been favored for their manurial properties; they have also been dried and mixed with dried yeast to form a cattle food or a fertilizer, and both applications are said to be very successful.

The wort, after remaining on the cooler a sufficient time, is drawn off, to avoid it falling below a temperature of 140 ºF, over vertical (such as “Baudelot” or “Lawrence”) or horizontal (such as “Morton”) refrigerators, in which the cooling medium is cold water of about 50 ºF., brine very rarely being used, and in no case that I heard of, direct expansion of ammonia. The temperature to which the wort is cooled is about 58 oF., the quantity of water required for the cooling being about 1½ to 2 barrels per barrel of wort.

No atomizers, or any such appliances, are in use for the aeration of wort on coolers.

Filtered air has been used in refrigerator or cooler rooms, but such a system has not made much progress.

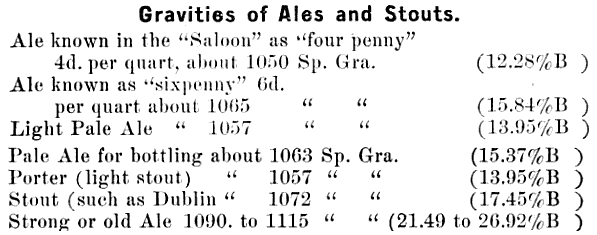

The cold wort runs direct from the refrigerators to the fermenting vessels. Here the pitching or seeding yeast is added, the quantity varying from 1 pound per barrel of say 1050 spec. grav. (12.28 % B) to 2 pounds or more to worts of 1070 spec. grav (17.0 % B ) and upwards, stronger worts requiring proportionately more yeast than the weaker ones.

Immediately a brew has been collected in the vessel which has been carefully gauged by the Excise Officers, what is known as a “dry dip” is taken, which means the measurement of the distance from the surface of the liquid to the top of the vessel a book of tables gives for this measurement the number of gallons contained in the vessel , and the Excise Officers taking this dip and the specific gravity of the wort, charge duty to the brewer at the legal rate, after making an allowance of 6 % for waste during fermentation and the filling into casks.

The brewer, before he commences to brew has made a declaration of the quantities he will use in the brew, and from these quantities the Excise Officers calculate a theoretical yield of wort, which if not obtained by the brewer, he is still charged for. So that you will see that the English operative brewer is to be certain of obtaining a yield equal to the theoretical quantity, otherwise the proprietors of the brewery would be paying duty upon wort which they have not obtained, but fortunately the standard fixed by the authorities is about 8 %, below its usual extract, in the case of malt, so that the brewer would be looked upon as a very poor operator if he did not obtain a yield at least equal to the standard. Still in many of the smaller breweries, or what are known as “Home- brewing Publicans”, this yield, in consequence of deficient apparatus, is not readily obtained, and often they are called upon to pay duty on materials used and not on the wort produced.

Fermentation of Ale and Stout.

The temperature at the commencement of fermentation is usually between 58 °F and 60 °F, and the increase of temperature during fermentation is controlled by passing water through copper coils, fixed in the vessel and below the surface of the wort.

The rate of fermentation is very rapid during the early stages, so much that in 36 hours after the commencement about one half (apparent) of the original gravity has been fermented, the temperature at this period being from 65 °F to 67 °F.

The systems of fermentation vary in different breweries, and are known as the Skimming, Dropping, Union and Stone-square systems.

The Skimming System.

In this system fermentation begins and is completed in the same vessel, the yeast being skimmed off the surface by means of “parachutes”, which can be raised or lowered by gearing, the yeast falling into slate or wooden vessels usually placed in the room below. The yeast is generally skimmed off, when the gravity has fallen to about 30 % (apparent) of the original, and the temperature is about 70 °F, the object being to have a finished fermentation in which the gravity (apparent) is about 25 % of the original.

The skimming period is about 60 to 70 hours from the commencement of fermentation. As the first layer of yeast is skimmed off, another covering is thrown up which, after an interval, is skimmed off until only a thin layer is left on the surface of the beer to protect it from the atmosphere.

After 6 or 7 days from the time of “pitching”, the beer is carefully run off into a vessel in a cool room, known as a “racking back”, it remains here a few hours and is then drawn off into small casks in which are placed from 4 lb. to 1 lb. hops of fine quality, per barrel which have been sieved free from seeds and small bracts, and are known as “hopping-down hops”.

Priming (a solution of cane, invert, or glucose sugars) is sometimes added while filling the casks, the quantity varying from 1 pint to ½ gallon per barrel, depending upon the gas condition required in the beer.

Aeration by blowing air into the fermenting wort, is quite unusual; although what is known as “rousing” is carried out by plunging into the wort stirrers which produce motion in the liquid and thus dispel gas.

The crop of yeast is four or five times the weight of the original seed yeast, and the middle skimmings are generally set aside for use in future fermentations. The loss of bulk during fermentation may be set down to about 2½ %.

The Dropping System.

In this system the fermentation instead of being completed in one vessel, the ale after being for 36 hours or so in the primary vessel, is run down into one or more shallow tubs, in which the liquid is at a depth of from 3 to 4 ft. These tubs are fitted with parachutes for skimming off the yeast, and attemperating coils for passing cold water through for controlling the fermentation.

The completion of fermentation and skimming are as in the system described above but the dropping from one vessel to another produces an aeration of the liquid which causes the yeast to rise more quickly to the surface and the yeast crop is found to be cleaner in consequence of the sedimentary matter of the wort being left behind in the primary vessel.

Again, the fermented liquid during the period between the end of skimming and the running down into the racking vessel below drops brilliant more quickly than when the fermentation is completed in one vessel, where the depth of the liquid is nearly twice as great as in the second vessel of the dropping system.

The after treatment of the beer during racking, storing, etc. is the same as in the skimming system.

The Union System.

In this system the beer, after fermentation to about half gravity, instead of being run into an open shallower vessel as in the Dropping System, it is run into large barrels known as “Unions” of about 150 to 200 gallons capacity, having inside a small attemperator coil. From the bungholes of these barrels, a small tube rises, having a bend in it at the top known as the “Swan’s Neck”, this bend being over a long narrow wooden trough, along the two sides of which are placed a number of the Unions. The yeast is discharged during fermentation through the swan necked pipes into the wooden vessel placed above it. The dropping of the yeast into this vessel brings about an aeration of the yeast.

In the yeast vessel beer separates from the yeast and this beer is returned to the unions at intervals until fermentation has ceased. The yeast in the vessel can be kept cool by attemperator pipes, through which water is passed.

About 7 days from the day of brewing, the ale is run off by means of a long, threaded tap passing through the bottom of the union, into a long wooden through which conveys is contents into the racking-back, where the beer is treated as in other systems.

This system is practically confined to Button-on-Trent.

The yeast is very strong in fermentative power and much thicker than in the Skimming and Dropping Systems.

It is not an economical system in consequence of the loss of bulk through the division into small quantities, but the flavor of the ales in consequence of the lessened exposure to the air between the finish of fermentation and racking, is considered to be better than that produced by other systems.

Stone-Square System.

This system is practically confined to Yorkshire in the North of England, where moorland water of a soft nature and malts produced from barleys grown on a heavy soil, and consequently of a tough nature, although the corns are large in size, are generally used for brewing purposes.

The wort in this case is run into a vessel which is rather deep, but is divided by a horizontal partition, having in it a man-hole. The wort is run into the lower chamber and the yeast works up through the man-hole, the neck of which is several inches above the partition. Now a quantity of beer is pumped into the upper chamber and there thoroughly mixed with the yeast, which is then run down into the lower one by opening a valve in the partition. This pumping and rousing takes place at fixed intervals, which results in thorough aeration of the wort and produces a satisfactory fermentation and gives a large yeast crop with cells of an unusual size.

The fermenting liquid is kept cool during fermentation by circulating water in a jacket, formed by a stone casing around the lower chamber.

In all systems of fermentation, it is usual to mix the yeast with some warm wort at a temperature of from 70 °F to 75 ºF, before pitching, or first running a quantity of warm wort into the fermenting vessel and adding the yeast thereto.

Yeast Storage.

Yeast is usually stored in wooden or slate vessels, sometimes placed in a room kept cool by means of brine pipes. Any beer that separates from it is drawn off and passed with surplus yeast into a yeast press, the filtrate being afterwards blended off in the finished beer. Before mixing up the yeast for future use, the top layer is usually skimmed off.

Washing of yeast is rarely practiced. Pure yeast (single cell system) has been tried in two or three breweries in Great Britain, but with very little success; beers produced by the same are said to have suffered in loss of flavor and the after fermentations in cask have not been satisfactory, there being a tendency to flatness.

Storage of Ales.

A very small quantity of English ales is stored in vats, but stout is still matured in large oak vessels of great capacity, particularly by Messrs. Guinness and other Irish brewers. Otherwise, the fermented ale is run directly into the trade casks and these are kept in the beer storage; having a temperature of about 55 ºF, for a few days in the case of mild ales for quick consumption, (but for several months in the case of pale ales for draught and bottling purposes and strong ales of 1090 to 1110 Sp. Grav. 21.49 % – 25.85 % B).

During this period of storage, the ale is not interfered with in anyway, except that any excess pressure produced by this fermentation is relieved by inserting in the bung what is known as a porous peg, which is a small peg made of very porous wood.

When the time of delivery arrives, the casks are filled up and finings are added to the casks, so that when a cask is placed in a customer’s cellar, the beer quickly brightens.

Krausening of beer is very rarely practiced, and I have not heard of the use of chips.

The beer on arrival in the customer’s cellar is allowed to settle from a few hours up to several weeks, according to whether it is a mild ale (quick consumption) or a pale or strong ale, stronger ales requiring a longer period to brighten, although it would be considered a very stubborn beer which was not absolutely brilliant within one week of delivery.

The gas condition of beer in the customer’s cellar is regulated by a porous peg, as in the beer storage.

Excessive condition is very difficult to deal with in the customer’s cellar, as the beer is drawn for distribution in the “Bar” (Saloon) by the aid of a pump, which would cause the sediment to rise in the barrel if there was too much gas condition in the beer.

Beer is not drawn through pipes kept cool by means of water or ice as in this country.

Drawing by means of gas or air pressure has been tried, but the cost and the fact that the English casks are not made to withstand this additional pressure, have much retarded the application of such systems. It is probable, however, that within the near future a gradual disappearance of the pumping systems, to which there are many objections, will take place.

Stout Brewing.

This is practically carried out on the same lines as ale brewing, except that very little malt substitutes are used, the grist contains about 10 % of roasted malt, the wort is boiled under pressure, fermentation is on the dropping system, the stout is stored in vats and a blend of old or matured stout and fresh or mild stout is sent out, the quantity of old stout being greater when required for bottling or export purposes.

Bottling Ales.

Only the highest quality ales are bottled under the ordinary system of bottling, i.e., where the beer is drawn off directly from the cask into the bottle without any chilling, filtering or carbonating. Such beer is bottled in the spring or late autumn of the year from what are known as March and October brewings, and after being stored in bottle at a temperature of about 55 o F, for three months or so, are looked upon to produce perfect bottled beers.

The beer for bottling may be on storage for two or three months before it is in proper condition for bottling.

The system of chilling, filtering and carbonating beers has only been introduced during the past few years, and seems to make good headway.

In some cases, the ale is stored in casks or glass enameled steel tanks at the usual cellar temperature of 55 °F. for sufficient time to develop cask fermentation and hop flavor, and is then placed in a cold cellar of about 32 °F. for 7 to 28 days, afterwards filtered and bottled without carbonation. Such ales excel by the delicacy of flavor and aroma.

Pasteurizing is not practiced in England, as such treatment impairs the flavor of the ales.

Stout is bottled from the cask after it has been on storage for a short time and as soon as it has sufficient gas condition.

Brewing Barleys and Malts.

I have previously referred to the materials employed in English breweries, but wish to give some additional information regarding the character of their malts.

Through the courtesy of Mr. Baird, of Hugh Baird & Son, Glasgow, I am in a position to produce here samples of barley and malt which show very interesting results. I also take pleasure in producing charts showing the methods of procedure in Baird’s malt houses, of two samples of malt from Scotch barley. The first sample is high dried, the other dried at lower temperature. The methods of malting are briefly as follows:

The barley is steeped for 72 hours, the water is changed four times, and every time the water is taken off, three hours is allowed for draining. The temperature of the steep is 42-43 °F. The malt remains on the floor twelve days, and the temperatures during these days are very interesting. The temperature on the first day is 46-48; on the second day, 48-52; on the third day, 52-55; and on the fourth day from 55-60. On the fifth day it remains constant, and rises on the sixth day to 63, which temperature also prevails on the seventh day. The temperature rises to 64 on the eighth day, remains constant on the ninth and tenth days, rises to 65 on the eleventh day, and finally reaches, on the twelfth day, the temperature of 68.

The total time of kilning is four days. On the 1st day the temperature is 95 to 105; on the 2nd day, 105 to 140; rises on the 3rd day from 140 to 205; on the 4th day it is 210, and is finished at this temperature, and kept there for eighteen hours.

The other sample of Scotch barley (low dried) remains in the steep also 72 hours, 12 days on the floor, and 4 days on the kiln. The temperatures on the floor are almost identical with the first sample. The temperature on the kiln on the 1st day is about 100, and the temperature increases slowly and steadily to 185 on the 4th day, at which temperature the malt is kilned off for 8 hours.

Coming now to the chemical analysis of the barleys, you will find that the amount of nitrogen varies greatly. It is lowest in the Scotch barley (8.31 %), and highest in the Ouschac (11.87 %).

A very striking feature is the amount of spelt, varying from 7.40 % in the Scotch to 16.38 % in the Gaza. The Scotch barley is very full-kerneled, while the Gaza has a long-shaped, oats-like appearance.

Regarding the malts you will see that the amount of extract varies considerably, which is as low as 66.43 % in the Gaza, and as high as 80.10 % in the Scotch malt.

These results show plainly to what extent the percentage of husks influences the yield obtained. Compared with the yield of our malts, we find that the percentage found in the Gaza is below ours. The yield in the two Scotch barleys is far above any extract we obtain, and is as large as the extract obtained from good corn.

Regarding the mellowness, we find that all samples with the exception of No. 4, show up very well. This, together with the fact that the development of the acrospire, is kept back by conducting the germination at cool temperatures, proves the perfect art of the English maltster.

The color of the worts is very much darker than we can employ for the production of pale beers, and necessitates the employment of pale sugar, and very careful handling in boiling, in order to produce a pale wort.

The flavor of the mash in all cases is very good and aromatic, which is to be expected in view of the careful kilning, and the high temperatures prevailing during the malting process.

Regarding the appearance of the wort, we find that only samples 2, 5 and 6 run off brilliant, 4 runs off opalescent, while 1 and 3 are turbid. Such malts, which run off hazy, do not find favor with our brewers, as it has been their experience that they give rise to difficulties in the clarification of the beers, and impair the brilliancy and keeping quality of the product.

As all these malts certainly have been made with the greatest care on the floor, we cannot attribute this phenomenon to faulty methods of malting.

According to Dr. Robt. Wahl, this behavior is to be attributed to the percentage of nitrogen. However, here is a very striking result: The California malt. with a nitrogen percentage of 8.56 runs off cloudy, while the Scotch, with a nitrogen percentage of 8.31 filters brilliant, and the Gaza with a nitrogen percentage of over 10, also runs off cloudy. If, therefore, the amount of nitrogen is the cause of this phenomenon, it is to be expected that the Scotch malts should behave in the same manner as the California. As this is not the case, the inference is justified, that it is, not the amount of nitrogenous bodies that cause such disturbances, but rather their quality. We will do well to attack the nitrogen problem with this end in view.

All malts are distinguished by their low percentage of moisture, which allows very fine grinding and, together with the fine dissolution of the mealbody, insures a very high practical yield.

Brewery Plants.

Compared with our elegant and beautifully equipped plants, the English breweries are simple and primitive to the extreme, and are devoid of all beauty and splendor. The plants seem to be constructed without proper consideration for saving of space and labor. This, however, can be explained by the fact that most of these breweries started small, and by continuous additions have reached their present large capacity.

To go further into the construction of English breweries would require a separate paper, and I should like to speak at length of the different breweries which I have visited. However, I prefer to postpone this for a future occasion, and shall confine my remarks to the visit of the brewery of Bass and Co., Burton-on-Trent.

Like certain events impress themselves very much on our minds, so the visit to this brewery will never be forgotten. It is over a year ago since Mr. O’Sullivan entertained our party at luncheon, but his charming personality stands vivid before me, and none of the participants will ever forget his cordial, welcome speech, or the response by Dr. Wiley, whose ready wit is known to us all, and the genial answer of Professor Chandler, of Columbia University.

Among the invited guests were a large number of English and American brewers and scientists: Messrs. Matthews, Lott, Stern, Jas. O’Sullivan, Tyrer, Parker, and many others. The photograph, taken by our fellow chemist, Mr. Lothair Kohnstamm, shows our party relishing the product of the brewery.

Of the extension of this plant, one might get an idea, when I say that the business premises extend to about 750 acres. The company has a net – work of 17 miles of railway lines, and has in constant use 120 railway cars for the purpose of transporting malt, casks, coal, etc., over its private lines. There are three breweries at the premises: the new, the middle, and the old. Of these the newest is the so-called “Old Brewery,” which is the most modern of the three. At the Old Brewery there are seven mash-tubs, each one placed under its own Hopper on the floor above. The three breweries contain 21 coppers, 12 at the old, 9 at the middle, and 8 at the New Brewery.

From the coppers the wort passes to the “hop-back,” and from here is pumped up to the top of the building on the other side of the yard into the coolers. These are great shallow tanks, 47 feet by 39, in which the wort lies to a depth of a few inches.

From the coolers the wort runs to the refrigerators, where, by passing over pipes in which cold water is circulating, it is rapidly cooled.

From the refrigerators the wort passes through pipes to the Square room below, where the yeast is added. Here the wort is distributed by shallow movable troughs among the squares for which it is destined. These squares are six feet deep, and contain 2,200 gallons apiece. There are 114 of these squares in the room.

When the fermentation has proceeded far enough the beer runs down into the Union Room to be cleansed of the yeast. There are three Union Rooms in the Old Brewery containing over 2,100 union casks. These lie side by side in double rows, and above each row is a long shallow trough called the “barm-trough.” It is a striking sight to stand at the entrance of the room and watch the hundreds of swannecks, the yeast dripping slowly into the trough.

When the ale is thoroughly cleansed it is run off into large “squares” in the Racking Room, on the ground floor, where the casks are filled.

The steam cooper shop is one of the most interesting parts of the entire brewery, and probably the finest and most up-to-date cooperage plant in the world.

All cooperage and casks used in the brewery are made on the premises, also the spiles and porous pegs. The latter are made of porous oak, and are for “venting” the ale when fermenting in cask; the spiles are of solid oak, and are for sampling or closing the vent after fermentation has ceased. There are also machines for making shives or wooden bungs. The machines are capable of turning out 25,000 spiles and 120 gross of shives a day.

It is impossible for me to discuss more fully all the features of interest seen in the cooper shop, but the manner in which the sawdust and chippings are removed from the building should not be omitted. At frequent intervals are openings in the floor into large pipes running underneath, along which a powerful current of air is driven by a fan. All the dust and chippings are swept into these pipes and carried by the air current across the yard into a large hopper, where they are stored or discharged direct into the railway cars which are to take them away.

General Trade Conditions.

Anyone may start a brewery by making a small payment for a license to the Excise Department, but before using any vessels he has to have them gauged by the Excise authorities, who visit the brewery when a brew is about to take place.

The brewery, as before explained, has to pay duty on the beer produced or the materials used, and the penalties for wrong declaration or concealment of wort are very heavy.

There is no restriction or duties to be paid in connection with malting. Most of the malt is made by malsters, who sell to the brewer, but since by amalgamation, brewery companies have become much larger, there is a tendency for brewers to become their own malsters.

Most of the publichouses to which beer is sent by the brewers are owned by the brewery companies, and are known as “tied houses” – that is to say, the tenants of the same are not permitted to purchase their supplies other than from the brewers who own the properties.

Publichouse licenses are very difficult to obtain. The licenses are granted by an application to magistrates, who must not be in any way connected with the trade, either directly or indirectly, such as by holding shares in any brewery company. Inhabitants can oppose the granting of a license by appearing at the court, but all licenses which permit beer to be sold on the premises and granted before the year 1904 cannot be refused without the holder is compensated for the closing of his premises.

Beer is also sold from premises known as off licenses, the license of which only allows the sale for consumption off the premises – that is to say there is no drinking at a counter.

The applicant for a license has to produce evidence of good character, and the penalties for infringements of the Licensing Law for such offences as permitting drunkenness, serving drunken persons, serving young children, or selling during prohibited hours are very severe, often resulting in the forfeiture of the license.

The net price to the saloon-keeper will vary from about 5½ dollars in the case of “fourpenny” to 13 dollars in the case of strong ale, per barrel of 36 gallons.

The retail prices of beer are low, it being possible to obtain a pint (fully half litre) of beer about 1050 sp. Gr. for two cents.

Publichouses have usually their “bar” divided into several compartments, one known as “outdoor department,” where beer and spirits are sold for consumption off the premises, another compartment where glasses of beer only are sold. The smoking-room of a publichouse is generally looked upon as the place where the best class of customers is found, and in which the best quality of goods is sold.

Publichouses are usually the meeting places of Friendly Societies and Trade Unions. the larger hotels are also used for Masonic meetings.

Some publichouses do not sell spirits, and are known as beerhouses.

Many of the breweries supply the customer direct at his house, the smallest size casks sold being 4½ gallons, known as “Pins”. The bottled beer trade seems gradually displacing the small cask, as the bottle is a more convenient method of handling beer and its contents are more uniform in character than when beer is drawn off from a cask, the last quantities of which are very flat and insipid.

The competition between the great breweries and the excessive prices paid for public houses resulted for a time in a decrease in the quality of the article, but as it has been realized that the better article naturally appeals to the public, competition is, in future, more likely to be on quality rather than lowness in price and lower gravity of beers.

Continental lager beer does not seem to advance in favour its consumption being confined chiefly to foreigners. The production of English lager beer seems to be the monopoly of Alsop & Co., Burton-on-Trent, who, some years ago, erected a large plant.

While the sale of lager beer is comparatively limited, the consumption of sparkling ale which possesses the character and flavor of ale, and the brilliancy and foam of lager beer is steadily on the increase.

Mr. Schram: – I have no doubt that all present will feel under obligation to Dr. Wallerstein for his very interesting lecture.

Before concluding the program of the evening, I want to say something regarding the pure food law. There is no doubt that all of you will be more or less interested in the provisions of the new law. I have visited the authorities upon whom the enforcement of this law depends in a measure, and found that standards have not yet been formulated and may not for some time to come.

The probability is, that sometime in the spring a committee of scientists will meet. It is the same committee which went out of commission on the 30th of June.

They proposed a standard for Lager Beer and Malt Beer, but finally, probably as a result of our urgent arguments, this was pushed into the background.

Now the Secretary of Agriculture has reinstated this body as a sort of advisory committee. This committee is com- posed of the official chemists of the various agricultural stations. It is an organization something like the A. B. I., and they call themselves the Society of Official Agricultural Chemists.

They do not formulate standards, but advise the Secretary of Agriculture, as to the purity and wholesomeness of food articles.

They stated that they would take up the malt liquor question at the same time as whisky and spirits, but we protested very vigorously, stating that we did not want to be considered at the same time as the whisky interests – we did not want to be closely associated with them.

It is probable that the Department of Agriculture will not take the matter up until spring.

It seems likely that brewing sugar will be excluded from the product known as lager beer, ale or Porter. If this should be carried out it would be necessary to call this product by some other name, or it should be stated on the label that sugar or glucose was used in the manufacture of the product. The Committee of the U. S. Brewers Association having the matter in charge, are making strenuous efforts to retain brewing sugars as an ingredient of standard malt liquors .

Preservatives will be absolutely forbidden, because they come under the heading of “Forbidding the Use of Deleterious Substances.”

Prior to adjournment Mr. Schram offered to give the enquiring members detailed information as to the provisions of the pure food law, and invited all members who desired to avail themselves of the offer to communicate with him on the subject.

There being no other business the meeting was adjourned.