MEETING HELD FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 19th, 1897, AT THE CRITERION RESTAURANT.

Mr. Arthur C. Tanqueray, President, in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed:—

On the Boiling of Worts.

By C. H. Field, F.I.C.

The principal objects we aim at in thoroughly boiling or cooking our worts are :—

1. The more or less complete extraction of the constituents of the hops.

2. The precipitation by heat and by the combined action of heat and the hop tannin of a portion of the complex nitrogenous matters.

3. The fixation of the carbohydrate constituents of the wort and the determination of the flavour or character of the beer by the method of boiling adopted.

In carrying out these operations, due regard has to be paid to their effect on the colour of the beer produced.

With regard to the extraction of the hops, as the results of a large amount of very able research work have already been published on this subject, it would be futile for me to go deeply into the matter. According to Hayduck, when boiling vigorously in an open copper, owing to the splashing and consequent intermixture of air, we get a larger proportion of the soft resins oxidised into a harder type than when a covered copper is used; these hard resins give a harsh flavor to the beers, which is particularly objectionable in the lighter pale ales, and necessitates great care in the selection of hops employed and probably a restriction of the time of boiling.

A short time back I had an opportunity of testing the difference between the beers from two coppers, one being domed in and the other open, the coppers being practically the same shape and both boiled for the same time by steam at the same pressure, with the same quantity and growth of hops. The beers boiled in the open copper had a distinct harshness, which was not perceptible in those from the domed copper.

This open copper was subsequently covered in, with the result that the beers boiled in it were entirely free from the harshness which was previously observed.

This all seems to substantiate practically what Hnyduck has found by experiment, and in the case, at least, of the- more delicate flavoured beers, points to an advantage in favour of covered coppers.

The nitrogenous substances which come under our second heading are so complex in composition and so prone to change that in the present state of our knowledge it is difficult to say what alterations really do take place. They are, however, roughly divisible into three types, viz.:

Albumins,

Peptones, and

Amides and amines.

There are, undoubtedly, numerous intermediate bodies, forming, as it were, stepping-stones from one to the other of these types, some being closely allied to the albumins and others to the peptones, and so on.

The albumins are coagulated by the boiling heat alone, even at temperatures somewhat below 212° F.

The peptones require the combined action of heat and tannic acid for their precipitation and subsequent coagulation.

It is noteworthy that the farther we get from the albumins and the nearer the peptones in our series the larger is the amount of tannin requisite to precipitate a given quantity of peptonic matter. It is generally considered that these intermediate nitrogenous substances, which range between the albumins and peptones, form a ready nutriment for bacterial growths; hence they should be carefully removed from the worts prior to fermentation. This is assured by coagulation in the copper, careful hop-back filtration, and final deposition on coolers, and we find 8 to 12 lbs. of hops per quarter generally sufficient, for all these purposes.

On the other hand, it will be our object to leave in solution those peptones and the amides and amines, which, being readily diffusible through the cell membrane of the yeast, are so necessary for the healthy reproduction of that organism.

It may be worthwhile to mention in passing that in all probability a combination takes place between a portion of the tannin and the diffusible peptones and remains in solution, owing, perhaps, to there being insufficient tannin to complete the precipitation.

We have next to consider the effect of boiling in increasing the stability of the carbohydrate constituents of the beer. It is admitted that the boiling does fix some of the dextrin combinations in such a way as to give them greater resisting power to the action of the yeast in the primary fermentation. The higher the temperature at which we boil, the greater the power of resistance developed.

As a practical illustration of this, if we take a concentrated solution of dextrin and give it a long boil (and being concentrated, the boiling point is naturally comparatively high), we can so alter it as to make it practically unfermentable or only very slowly reducible by the yeast action, this resisting power varying according to the length and temperature of boil. From this it is reasonable to argue that the same thing, but to a less marked extent, goes on in our brewing copper, such factors as depth of wort, concentration and whether our copper in closed or open determining the amount of stability obtained. Hence it seems to me that, provided we are not interfering with the colour or flavour of the worts, the higher the temperature at which we boil, the more stable should our resulting beers be.

In speaking of the effect of boiling on the colour and character of beer, the form of copper used and the method of boiling adopted may be taken as the determining influences in this direction, these applying more particularly to the production of light pale ales, where any objectionable characteristics arc so easily detected.

Coppers in general use are either boiled by direct fire-heat or by steam, which cither circulates through a jacket, or steam coil, and in some cases is blown directly into the wort itself. They can be either open or closed in. If the former, the boil takes place under ordinary atmospheric conditions; if covered in, we can regulate the pressure, and hence the temperature, of the boil at discretion. Various appliances are introduced with the object of increasing circulation and preventing boiling over, such as fountains, loose covers, &c.

I shall make no further allusion to the use of free steam as a boiling agent, as I consider it too dangerous for practical work, owing to the objectionable flavours that are apt to be imparted by it.

With respect to the temperature of the boiling wort, this naturally varies with the depth of the wort and its density, and the amount of hops used. Although we hear of worts boiling in an open copper at a temperatnre of 220° F., yet, myself, I have never found the mean temperature of a wort of 30 lbs. weight to reach more than 216—217° in any copper I have tried, nor could I detect any difference in the boiling temperature when using a fire or steam copper, but the depth of the wort does raise the temperature slightly.

In comparing the difference (if any) between a fire and a steam boil, in the case of fire we have to consider the temperature of the flame playing on the sides and bottom of the copper, which is from 1112—1472° F. Now, with a steam-jacketed copper, using steam at, say, 60 lbs. pressure, we only get a temperature of 152° C, or 307° F. This difference, however, is far more apparent than real, owing to the large amount of latent heat contained in steam as compared with that of the furnace gases.

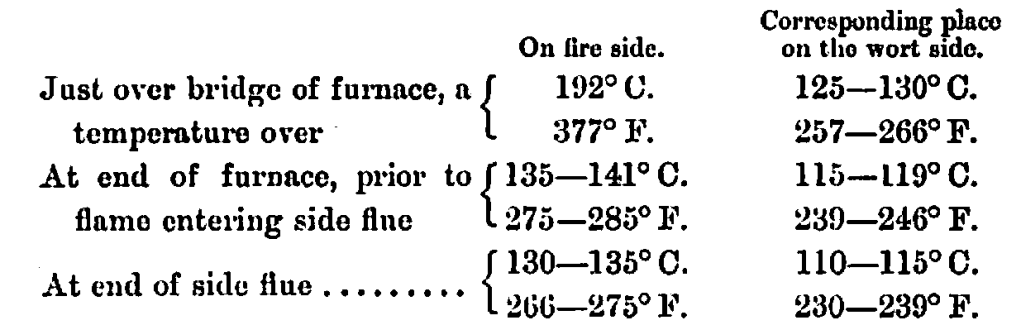

Reverting to the first point, Schwachhöfer has found, by fixing alloys of metals with various melting points on the bottom and sides of a copper and on both sides of same, i.e., on the wort and furnace side, the following temperatures:—

Thus we see that although the fire raises the temperature of the bottom of copper to 192° C. (377° F.) on the furnace side, yet on the corresponding place on the inside it is reduced to 125—130° C. (257—266° F.), but even this appears to be a high temperature to expose a wort to, as it is the actual temperature of the surface on which the wort impinges.

Some time since, I had the opportunity of testing the temperatures existing when boiling with a steam-jacketed copper of 30 barrels capacity. The highest temperature we could reach (with a pressure of 60 lbs. steam) on the wort side in the middle of the bottom was 115° C. (239° P.), this being therefore the highest temperature on which the wort impinged. From this it appears that when boiling with fire the wort comes in contact with surfaces of a temperature of from 10—15° C. (18—27° P.) higher than when using steam. Whether this difference may be sufficient to increase the fulness of a beer by more thoroughly cooking some portion of the albuminoids or by a greater fixation of the carbohydrates is a matter giving scope for a variety of individual opinions.

In considering the matter from another point of view, i.e., the amount of potential heat contained in steam as compared to furnace gases, we alter the complexion of the whole case.

The temperature of furnace gases is, say, 600—800° C. (1112—1472° F.), whereas the temperature of steam at 50 lbs. pressure is only 148° C. (298° F.), but this great difference in temperature and consequent apparent disadvantage is largely counterbalanced by the vastly superior conductivity of steam. For each 1° C. in the difference of temperature between the heating medium and the wort per square metre of heating surface per hour we transmit by steam = 650 cal., i.e., units of heat, and by the gases from a furnace = 20 cal.

This large difference shows the great capacity which steam has for holding and transmitting heat as compared with furnace gases.

One c.c. of steam at 40 lbs. weighs 1·97 kilo., and equals 1278 cal.

One c.c. of furnace gas at 600° C. weighs 0·42 kilo., and equals 60cal.

On boiling a wort that has a temperature of 100° C. (212° F.), the differences are as follows :—

The coefficient of conductivity per hour per square metre of heating surface by—

i.e., the heating capacity of steam to that of the furnace gases weight for weight is 2½ — 1°.

In examining this large heating capacity of steam we find it chiefly exists in the form of latent heat at the rato of 537 cal. per kilo., whether we work at a high or a low pressure.

The conclusions, therefore, which we are justified in drawing seem to be that in boiling with steam we get more actual units of heat taken up, bat the wort is in contact with the lower temperatures. On the other hand, with fire boiling we have fewer units of heat taken up, but the wort is in contact with much higher temperatures. Opinions seem to be divided as to the effect these differing conditions have on the finished beer, but my own experience leads me to the conclusion that, providing care is exercised to keep up a steady pressure of 50 lbs. of steam throughout the boiling period, equally good results so far as stability and character of the finished beer are concerned can be obtained with steam as when boiling with fire.

There seems to be considerable divergence of opinion as to the advantages or the reverse of pressure boiling. Setting aside the effect of the higher temperatures at which the wort is boiled when under pressure, the most important consideration seems to be that of circulation and its effect on the colour of the wort. I am inclined to think that circulation is not nearly so rapid in a pressure copper as when boiling without pressure. If that is so we should certainly get a considerably greater increase of colour in the former case than the latter.

In preparing a paper of this description I have been obliged to go over some old ground, which I hope has not made it too wearisome to you. At the same time, if 1 have been able to bring before you something of interest to you I am very pleased.

DISCUSSION

The President said they had to thank Mr. Field for an interesting paper dealing with a subject of great, importance to all brewers, and he should have liked to have gone more thoroughly into the figures which had been put before them before expressing an opinion upon them. He could not quite see how the great heat which in some instances seemed to be passing through the bottom of the copper was disposed of. He had always thought that the maximum temperature to which a wort of an ordinary depth in a copper could be raised was about 220—230° F. The heat of the vesicles of steam at the bottom depended very much on the depth of the wort in the copper. Of course the highest temperature would be at the bottom of the copper, where the dry steam was formed which broke up into vesicles and rose up through the wort. With regard to the question of boiling as a whole, he thought the great difference was between what might be termed boiling and cooking respectively. It depended entirely on the temperature at which the steam vesicles rose up through the wort. Ho quite agreed with Mr. Field that good results were obtainable both by steam boiling and direct fire boiling, but he thought the main secret of steam boiling was that the steam should be at such a temperature that the vesicles met particles of the wort at a temperature capable of cooking them, and not merely of boiling them.

Mr. ALDOUS said he had received a letter from a member who lived a long distance from London and was not able to attend the meeting. He was about to put up a new copper and thought of boiling by steam, and he wished to obtain if possible some information from Mr. Field or any other member whether steam boiling under pressure in a domed copper did produce any charring effect, or if not, whether it acted as well as an ordinary fire. Probably some of the London members could give him some information as to the effect of boiling worts under pressure with an ordinary fire, but he did not remember seeing a copper in London where the worts were boiled under pressure by means of steam.

Mr. HILL asked if any material change was effected by boiling in an open copper in converting the soft resins of the hops into the hard resins, and if the author bud determined the amount of any change of that kind.

Mr. CANNON said the author had stated that the temperature and duration of boiling determined the composition of the resulting wort so far as its fermentability was concerned. He was unable, however, to understand how that could be. The quantity of dextrins or malto-dextrins in a wort determined its fermentability, and it was well known that these substances were not farther hydrolysed after the diastase had been coagulated and its hydrolytic power destroyed. In fact, a solution of diastase was rendered inactive at 180° F., and completely destroyed at 212° F., and that being so, he could not see how any difference in the fermentability of the wort could be produced by prolonged heating beyond that temperature. Another point which did not seem to have been considered was that in fire-heated coppers there was an enormous temperature on the outside of the copper, and a slightly less one inside, and surprise had been expressed why the wort did not become charred. Apart from the fact that the body of the wort considerably lowered the temperature of the gases impinging upon the plates and a large amount of heat was rendered latent, it should not be forgotten that there was practically a layer of steam over the heating surface of the copper, and that layer being non-conducting prevented the heat from reaching the wort, so that the high temperatures shown were more apparent than real. Under certain conditions from theoretical considerations ho could conceive it possible that higher temperatures would be attainable in a copper heated by high pressure steam than in one heated by fire.

Mr. FIELD, in reply, said he thought the best way of answering Mr. Caunon’s question was to recapitulate a portion of the paper in which it was stated that boiling did fix some of the dextrin combinations in such a way as to give them greater resisting power towards yeast.

Mr. CANNON said he still did not follow the argument. They all knew that dextrins were unfermentable in absence of diastase, and he did not see how continued boiling could render them more unfermentable after the diastase had been destroyed.

Mr. FIELD said Mr. Cannon seemed to overlook the influence certain yeasts had on dextrinous matters. He was quite right in saying that after boiling there could be no further hydrolytic action by the diastase, but it was well known that during fermentation (both primary and secondary) dextrinous substances were considerably modified by ferments, and his (Mr. Field’s) point was that careful boiling, and hence thorough cooking of the worts, gave them a greater resisting power to these ferments. He thought it would be found that if worts were not boiled at all, bat simply sterilised, there would be found great differences in the fermentability of the sugars. After prolonged boiling and concentration of the worts the carbohydrates would be fixed, so that they would not ferment, or only very slightly. Many of the non-fermentable sugars now sold were prepared in that way. It seemed to him feasible that n similar fixation might take place in the copper, although of course to a much less extent. In some experiments he had made several years ago, he found that by “boiling” at high temperatures a certain quantity of the soft resins were converted into the hard ones. There was a less rapid circulation in a covered copper as compared with an open one, and for pale ales he was inclined to think that too great an increase in colour would occur in the former. Pressure coppers were used by some brewers to produce fulness and increase the flavour.

Mr. ALDOUS said the point he wished to bring out was whether there was any marked difference between steam and fire heating in this respect, and whether if the worts were boiled by steam under pressure there would be any charring.

Mr. FIELD said the charring or colour seemed to be caused more particularly by the insufficient circulation of the wort than anything else. He was of opinion that, other conditions being similar, less coloration would result from boiling under pressure with steam than with fire. With very rapid circulation, the wort passed over the heated surfaces at a very quick rate; and naturally there was not much colour produced as if it were in a more quiescent state.

Mr. ALDOUS said he gathered that the circulation in the wort was decreased by exercising pressure upon it, and that would create charring to some extent, even if the boiling were done by steam.

Mr. FIELD said it would to some extent. It. was a matter for practical experience to determine in individual cases how much increased pressure could be used to advantage what boiling in a domed or covered copper as compared with an open one.

The PRESIDENT said it only remained to thank Mr. Field for his interesting paper. With regard to the question of coloration of worts in the copper, he did not think for one moment that the colour was produced by charring, namely, from the action of the wort against the sides or bottom of the copper, because there must be a thin coating of dry steam all over the surface. He rather thought it was the temperature at which the vesicles of steam rose through the wort which made the difference; and probably Mr. Field was right in suggesting that when the circulation of the vesicles of steam was slow in consequence of pressure they were more likely to act on the wort and produce the colour Mr. Aldous had spoken of.

Mr. ALDOUS said he only used the term charring to express the fact that colour might he obtained. He should like to know if colour was produced in pnle ales with a pressure of some 5 or 6 lbs. per square inch in the copper.

The PRESIDENT replied that he thought so.