ON THE MEASUREMENT OF FOAM

(Part of the experimental work in this paper has been used in connection with a lecture given by E. Helm at the Sixth Scandinavian Brewers’ Course of Study in Copenhagen, 1934.)

By E. Helm and O. C. Richardt (paper delivered April 1936)

Brewing literature is wanting in records of reliable and experimentally supported studies on the relation of the various malting and brewing processes to the foaming capacity of the finished product. There are numerous articles on the head of beer partly theoretical and partly practical (Liiers and Schmal, Z. ges. Brau., 1925, 59; Windisch, Woch. Bran., 1926, 162; Windisch, Kolbach and Banholzer, Woch. Brau., 1926, 207, this Journ., 1926, 366; Geys, Woch. Brau., 1926, 439, this Journ., 1926, 524; Krauss, Woch. Brau., 1932, 409; Helm, Woch. Brau., 1933, 241, this Journ., 1933, 564; Blom, Petit J. Brass., 1934, 388, this Journ., 1934, 254). The general purport of these researches shows that by means of foam measurements a connection has been found between the foam and other properties possessed by the beer; further, that conclusions may be drawn from certain malting or brewing conditions and foam retention of the beer. Most of the published work, the experimental in particular, is of doubtful value, largely on account of the methods adopted for measuring foam having been defective.

A method for the measurement of beer foam has been devised at tins laboratory, particulars of which were published in 1933 (Helm, loc. cit.). Considerable experience has now been gained on the application of the method and results obtained which wo consider are of sufficient interest to warrant a report on the same.

A method for measuring foam has been devised by J. Blom (loc. cit.), which will be briefly described later. It differs from the Carlsberg method in that the foam formation is effected not by means of the carbon dioxide contained in the beer, but by carbon dioxide introduced from without. Both methods depend on the principle that not the foam itself but the quantity of beer found in the foam is measured.

Methods of Procedure

- The Carlsberg Method. —The measurement of the foam is carried out as described (E. Helm, this Journ., 1933, 564).

The foam is formed in a natural way, viz., by the free fall of the beer. The amount of foam (volume of beer formed by the subsiding foam) left 2 minutes after the pouring out of the beer, is called the Total Foam, and is given as percentage of the total volume of beer. It is a measure of the foam formation capacity. Tho amount of foam left after 10 minutes and measured and expressed in the same way is called the Residual Foam. It is a measure of foam retention.

When not otherwise stated the beer is kept at 10° C. (50° F.) at least 20 hours before the measurement. The determination itself is made at 20° C. (68° F.). The figures shown in the tables represent, the average readings for 5-6 bottles, unless separate measurements for each bottle are given. In some cases the carbon dioxide content is shown in the tables, and where this is not the case the figures lie within the ordinary limits (0-35 0-42 per cent.).

- The Blom Method.—In this method (loc. cit.) 200 gm. of beer are poured into a separating funnel of special construction and the foam is formed by forcing the carbon dioxide at a constant pressure (175 cm. mercury) through a porous tile filter immersed in the beer. When the funnel is full of foam the beer is separated and the foam weighed at intervals of one minute, the foam subsiding into beer being drawn off immediately before weighing.

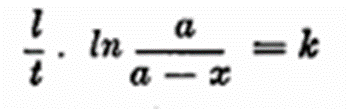

Blom deduces that the subsided foam per unit of time is proportional to the existing foam which is expressed by the formula

where t = time in minutes, a = gm. foam at time 0, x 1,2,3 = gm. foam after 1, 2, 3 minutes.

Instead of the natural logarithm, ln, Brigg’s logarithms are used.

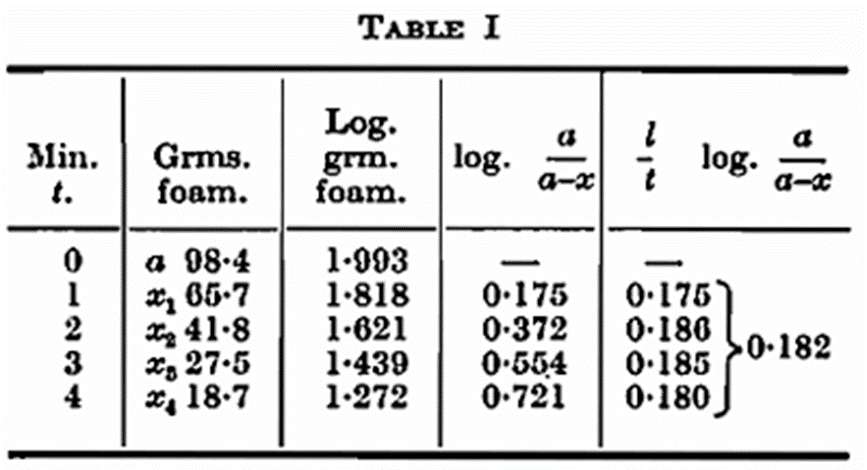

In Table I is shown an example of the Blom method.

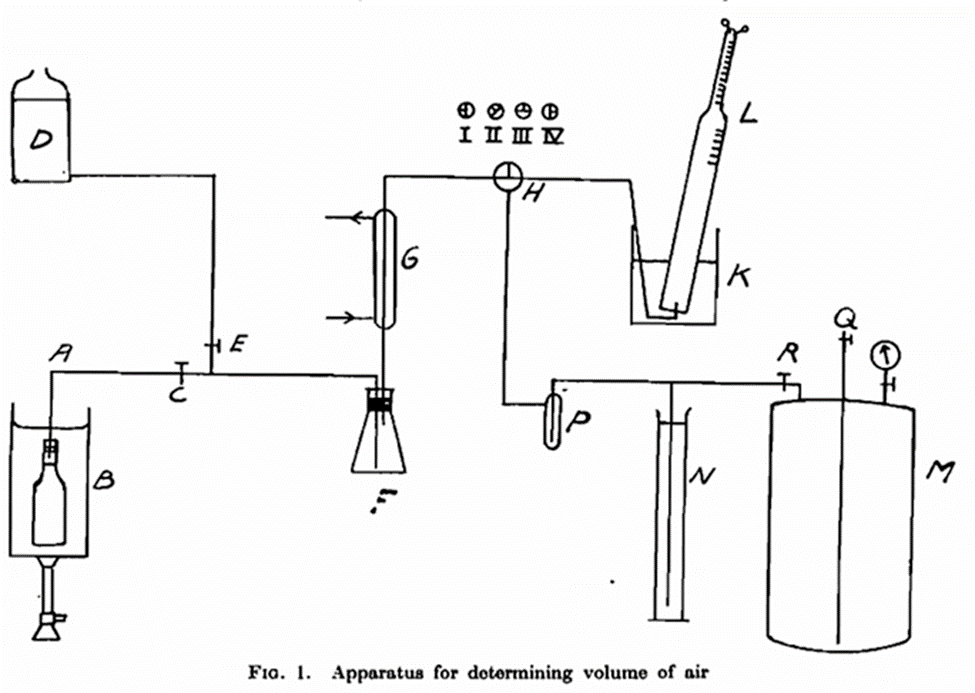

The constant k, in this case 0·182, is consequently an expression for the rate at which the foam subsides. For practical reasons Blom multiplies k by 1,000; this figure, 182, is called the foam constant. The greater the foam constant the poorer the foam retention, and vice versa. The measurements taken by this method are always carried out at a temperature of 20° C. (68° F.) both for beer and atmosphere. To facilitate a comparison between the two methods and to obtain figures running parallel with the foam retention it is preferable to use the expression

as expressing the foam retention.

As the conditions of foam formation by the Carlsberg method closely approach those of practice, the foam being formed by the free fall of the beer, but under fixed uniform conditions, it will be clear that the result of the measurement includes all the factors which in practice have influence on the foam. This is the main difference between the Carlsberg and the Blom method, as the foam formation in the latter method is brought about by means of carbon dioxide. Consequently, there need be no carbon dioxide in the beer, and foam measurements can be made even in beer residues or in the wort. Hence it is the capacity of the beer itself to form a retentive foam which is being investigated. The other factors, viz., the drawing off and taking of the sample, both of which, as will be shown later, largely affect the result when the foam is measured by the Carlsberg method, have proved, as should be expected, to be of secondary importance in the measuring of foam by the Blom method.

If it is desired to investigate the influence of the various malting and brewing conditions on the capacity of the beer itself to form a retentive foam, or to study the influence of certain chemical substances on the same, the Blom method is the better for the purpose. If, on the other hand, it is a question of obtaining a measurement of the foam properties in the beer ready for trade, the Carlsberg method would appear to serve the purpose. Tho results of this method, especially the residual foam figures, are more easily comparable with the direct observation of the consumer. To obtain a satisfactory average expression for the foam of a beer a number of bottles, e.g., 10-20, must be measured, drawn consecutively from the same machine. The variation between the residual foam figures for the single bottles is used as an expression for the uniformity of the drawing. The Carlsberg method can also be used for measuring the foam of beer in malting and brewing experiments, provided the necessary precautions in collecting the samples are observed. Such precautions have proven to be of material importance in connection with the study of other properties of the beer, viz., the biological keeping capacity (de Clerck, Petit J. Brass., 1934, 464; this Journ., 1934, 292, 407) and the tendency to become turbid [by formation of protein haze (Helm, 1934, loc. cit.)].

It is difficult to obtain a reliable standard for foam determination, as errors arise both from the measurement proper and from the drawing of the sample. These two sources of error cannot be kept separate with certainty, but approximately the error arising from the measurement proper can be estimated at about 4 per cent, for the Blom method and about 6 per cent, for the Carlsberg method.

The variations which are due to the sampling or drawing off will cause at most an error of about 10 per cent, in the Blom figures, whereas they may rise to 50-100 per cent, in the case of the Carlsberg method. As a rule, Blom’s figures for different beers will fall within the range of 4·4-5·7. On the other hand, the corresponding Carlsberg figures will cover a range of 0·5-2·0. The high percentage values of error in the Carlsberg method are reduced accordingly.

- The Collection of Samples. —The hand drawn samples are always collected from a container of filtered beer at a temperature about 1°C. (34° F.). Tho filling of the bottles, which as a rule are provided with patent stoppers, takes place through a sampling cock connected with a glass tube by means of a piece of rubber tubing; when held obliquely it is possible with some practice to fill the bottles without the formation of foam. With pasteurised beers, samples are taken immediately after the maximum temperature of 63-65° C. (145-149° F.) is reached.

- Determination of Air in Beer. —There are three different methods of procedure:

- Determination of dissolved air present in a sample of beer in a cask or other container; (2) determination of the dissolved air in a beer in a sealed bottle; and (3) determination of the total volume of air in the beer and in the space above it in a crown cork sealed bottle.

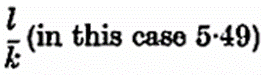

- For the determination of air, the beer is carefully drawn direct from the cask or container at cellar temperature into a bottle, which latter has previously boon filled with pure carbon dioxide. The bottles, which preferably should have a patent stopper, are filled right up to the top and closed in such a way as to leave no air bubbles on the surface of the beer. The carbon dioxide and the air are boiled out in an apparatus where the air can be determined volumetrically after the absorption of the carbon dioxide by caustic soda. The oxygen content in the air can then be determined eudiometrically in the usual manner by explosion with hydrogen. The bottle should be kept at cellar temperature and the patent stopper replaced by an ordinary cork having a glass tube A connected with the apparatus for the determination of air (see Fig. 1). Previously this has been filled with pure carbon dioxide from the container M (described later); the cork is fastened with metal wire and the bottle with its contents are boiled in a saturated solution of sodium chloride B. The carbon dioxide and the air, together with the beer and the foam, are thus forced over into the small Erlenmeyer-flask F. The beer condenses in the condenser G, and remains in the bulb whilst the foam subsides on contact with a small quantity of fatty acid placed on the sides of the bulb. The carbon dioxide and the air pass through the three-way cock H kept in position III, and bubbles up in the eudiometer tube L which is filled with about 5 N NaOH. By those means the carbon dioxide is absorbed and the air takes the place of the soda solution. By opening the cock very slightly the bubbles become smaller and the absorption takes place more rapidly. When all the air has been boiled out of the bottle A (i.e. when no more bubbles are observed) H is placed in position II. C is closed and E opened, His again placed in position III and the remaining air and carbon dioxide in the system is driven out by the saturated salt solution in the container D.

The eudiometer tube is shaken to absorb the last traces of carbon dioxide. The mouth is closed with a finger and the tube placed in a tall gloss cylinder containing water. After the levels have been adjusted the air space can be read off. To assist accuracy in reading the tube is narrowed at the extreme end (about 5 c.c). To determine the oxygen content in the air, a slightly smaller volume of hydrogen is added under water, and the mixture is exploded. One third of the volume which has disappeared will be oxygen. If the oxygen content is so low that the mixture does not explode, about the same quantity of oxyhydrogen is added from a small gasometer. (The latter quantity need not be read off as all the oxyhydrogen, provided it is pure, disappears on the explosion.)

Previously the whole apparatus must have been filled with carbon dioxide. As the steel tubes of carbon dioxide always contain a little air, and as the air in the flask after some time concentrates principally above the liquid carbon dioxide, the initial outflow of carbon dioxide will carry most of the air. To overcome this difficulty the tube of carbon dioxide is allowed to stand for 24 hours, and then about one-third of the contents is allowed to escape, after which the greater part of the air will have disappeared. To obtain a constant correction for the air content in the carbon dioxide the container M (Fig. 1), which holds 50 litres under a pressure of 2 atm. is used as a carbon dioxide reservoir, the air having been driven out by water injected through Q. In turn the water is replaced by the carbon dioxide from the steel tube injected through R.

The air in the apparatus is now expelled by filling the system with brine from D. Cock H remains in position III while F and G are entirely filled. C is closed when tube A is filled. Then H is placed in position I and the salt solution is forced back into D by the carbon dioxide from M which is conducted past the safety valve N and through a bubble glass P, by means of which the speed can be controlled. Then the cock H is placed in position IV and the carbon dioxide passes into the soda solution. Finally, the cock H is placed in position II and the system is now completely filled with carbon dioxide. This carbon dioxide contains a small quantity, about 0·1 per cent, of air, and it is therefore necessary to carry out a control determination before the test is performed.

The eudiometer tube filled with soda is placed over the mouth of the gloss tube and with H in position III the carbon dioxide is driven into the eudiometer tube by the brine. The volume of air is read off as described above, whereby a correction is obtained which must be deducted from all determinations made. Tho salt solution is again driven back into D by the carbon dioxide from M, and the apparatus is then ready for use.

(2) Before the determination of the air content of beer in sealed bottles is made, the bottle must be kept for about 2 days at 12o C. (53° F.) to effect a state of equilibrium. After this the bottle is carefully opened and is filled entirely with air-free distilled water, the subsequent method of procedure being the same as that described under (1).

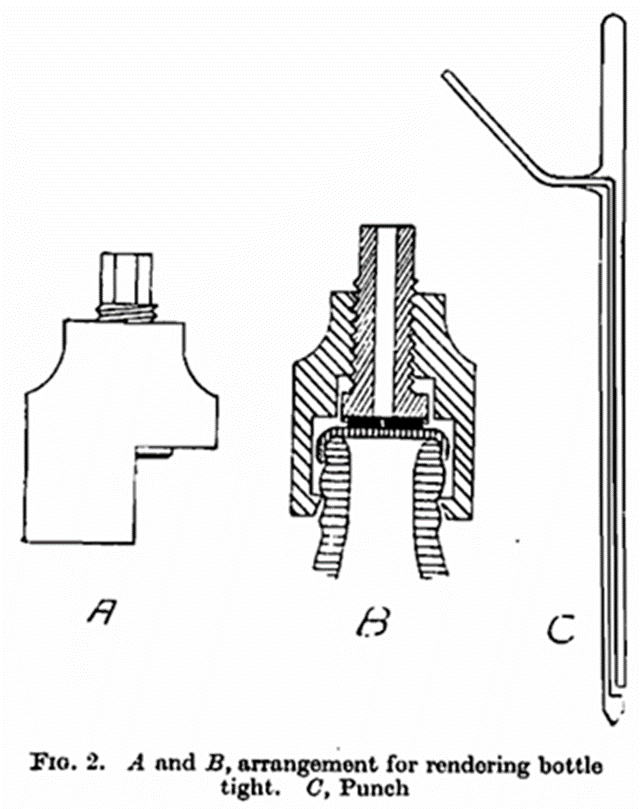

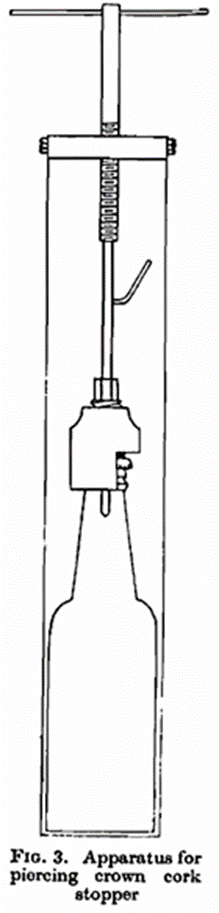

(3) For the determination of the total amount of air in crown cork sealed bottles, a device can be used to pierce the caps (see Fig. 2). This consists of a tightening arrangement (A and B) which presses a rubber packing (shown in black on the illustration) against the cap, whereupon the latter can be pierced with a punch (C) by means of a cramp (Fig. 3). The hole produced by the punch, is connected through the side tube with the cock (C) on the apparatus for the determination of air. The cramp, together with bottle packing and punch are placed in the salt solution so that the tightening apparatus is under the surface.

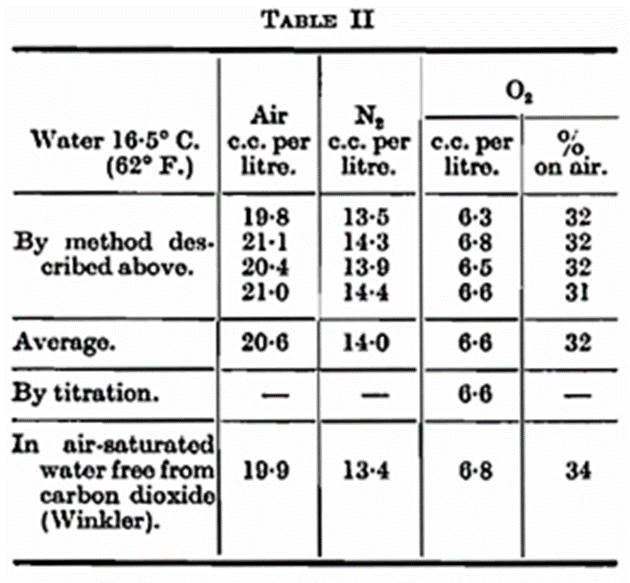

A method of this kind may, of course, be adopted for the determination of air in ordinary and mineral water. As a check on the accuracy of the method determinations of air have boon made in distilled water saturated with air-free carbon dioxide. Ten bottles were taken. In four of these the air was measured in the apparatus described, and the oxygen determined by explosion with hydrogen. In three bottles the oxygen was determined directly by Winkler’s method (reduction with alkaline manganous chloride and titration of the equivalent quantity of the iodine by sodium hyposulphite). The results are shown in Table II.

The following table shows the data of two experiments using the procedure described above.

Influence of Various Factors on the Foam

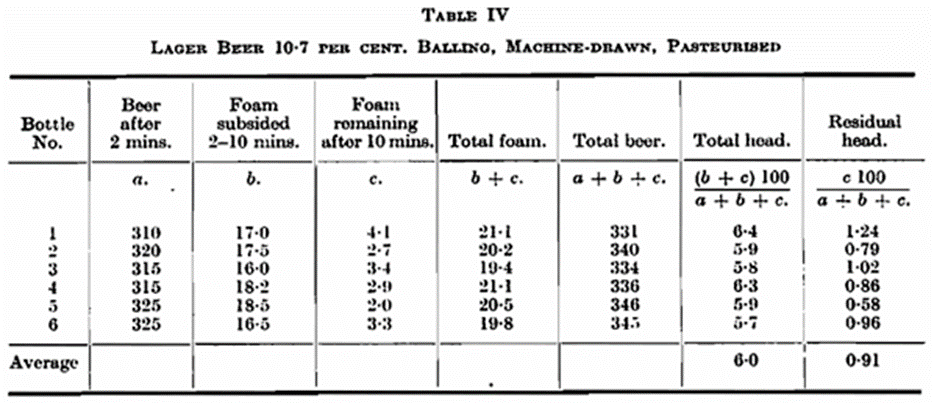

- Bottling of Samples. —Attention has already been directed to the great effect which the

manner of drawing off the sample has on the foam. It will be seen that foam measurements of samples taken by drawing off apparatuses give irregular results (see Table IV), and that samples drawn by hand give uniform results. At the time it was not possible to give explanation of the divergence, but a number of experiments with a view to elucidating the difference have since been carried out in this laboratory. From a container of lager beer three sets of samples were drawn off by hand in patent stoppered bottles. One set was drawn, very carefully, so that the beer did not foam, but ran smoothly into the bottle. Another set was drawn by a person unaccustomed to doing so, but who was instructed to fill the bottle as carefully as possible. A third set was drawn without exercising special care. The beer, in fact, foamed whilst being filled into the bottle. After pasteurising, the beer was warmed to 15° C. (59° F.) and the foam measured. The results are shown in Table V and demonstrate the great importance of sampling.

Table VI shows the results of foam measurements of samples drawn by hand and by machine. The samples shown in bottler C (Table VI) are arranged in bottles which have been filled smoothly and bottles which foamed on being filled. In bottler D the beer ran out very smoothly in such a way that none of the bottles foamed. Half of these samples were therefore made to foam by means of a blow on the bottle neck. None of the bottles had foamed so much that the beer had run over; consequently, there could only be a question of loss of carbon dioxide, whereas none of the beer itself or beer foam had been lost. The analyses also show that the loss of carbon dioxide has been very small.

Foam measurements were taken of samples which were drawn by hand from a container of filtered beer. Half of the bottles were filled in the ordinary way and the other half in an atmosphere of carbon dioxide, the bottles beforehand having been filled with carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide was injected into the bottle neck over the beer immediately prior to sealing. Foam measurements were taken after pasteurisation, the beer having been allowed to stand some days. These results (see Table VII) illustrate the great effect which the kind of gas contained in the bottle has upon foam retention.

Table VIII contains data affording a com parison of the foam retention for a number of beer samples measured both by the Blom and by the Carlsberg method in air-filled and CO2 filled bottles.

From these figures it appears that there is a fair agreement between the foam retention as determined by the Blom method and the residual foam by the Carlsberg method, but that the differences between the residual foam figures for the same beer samples in air and CO2-filled bottles are greater than between the foam retention figures arrived at by the Blom method.

Table IX shows the values of the residual foam found in the machine-drawn Pilsen beer samples. Samples No. 1 and 2 were drawn off smoothly and No. 2 samples had carbon dioxide blown into the bottle-neck above the beer immediately before sealing. This has caused a considerable decline in foam retention. Samples No. 3, 4 and 5 foamed on being drawn, No. 4 the same as No. 2 samples had had CO2 blown into the bottle-neck before being sealed; this, however, has had no influence, as the air had already been expelled by the foaming. On the other hand, No. 5 samples, the bottle-necks of which were filled with air after the foam had subsided, show a marked increase in foam retention.

Table X records a series of experiments in which the same beer has been drawn in different ways, partly smoothly and partly foaming, and partly under carbon dioxide and nitrogen. In addition to foam measurements by the Blom and Carlsberg methods, the air in the beer was determined by the method already described. Only the volume of air dissolved in the beer was determined, as the air in the bottle-neck was expelled with air free water prior to the analysis. The experiment is a further confirmation of the conditions demonstrated by the preceding experiments, viz., that the decline in the foam formation during machine-drawing was due to the air having been expelled by the foam or by the carbon dioxide released during the foaming.

It will be seen from the residual foam figures in the tables that beer drawn by hand without foaming possesses the best foam retention. The drawing of beer by machine, which is never as steady as drawing by hand, results in a smaller foam retention. Greater foaming, however, whether casual or artificially produced, results in a correspondingly greater decline in the residual foam. It might be imagined that the decline in the foam retention is due to loss of carbon dioxide. As that loss has been exceedingly small this explanation is improbable, and, as will be shown later (see Fig. 5), the variations in the carbon dioxide content within certain limits are without significance as regards the residual foam.

Raux (Brass. Malt., 1933, 71; this Journ., 1933, 499), too, has realised that foaming reduces the ability of the beer to form stable foam, and finds an explanation in the foam bubbles removing the colloids. This presumption is probably correct when the foaming is considerable. In cases, however, where there has been no question of loss of beer or foam, but only of foam which rises to the mouth of the bottle, this explanation can hardly apply.

Another explanation might be found in the expulsion of air as a result of the foaming. There is always in drawn-off beer more or less air, the volume of which varies considerably in the machine-drawn bottles, as is shown in Table XI. Thirty machine-drawn bottles were arranged in three sections and used respectively for the determination of total air and for foam measurements by the Blom and Carlsberg methods. It will be observed that the variations in the air are of a magnitude similar to the variations in the results of the foam measurements by the Carlsberg method. The head-retention capacity measured by the Blom method varies only slightly.

In extreme cases where the differences in the content of air were large, some bottles having been filled in an atmosphere of carbon dioxide, others in air, differences in the head retention capacity were also found by the Blom method, but the differences were less than those between the residual head figures.

In view of these circumstances no great agreement is to be expected between the two expressions for the head-retention capacity found by means of the two methods. On the other hand, a certain parallelism is generally found between the head retention capacity determined by the Blom method and our residual head values.

- Influence of the Gases in the Foam-on-Foam Retention Capacity. —Beer foam consists of a

very great number of small bubbles. The carbon dioxide enclosed in these bubbles will generally contain varying quantities of other gases (nitrogen and oxygen).

Taking into account the short duration of the experiments we will leave out of con sideration any chemical influence of the gas included upon the constituents of the film of the bubble. Hence for the same beer, at constant temperature only one group of factors remains which may be conceived as influencing the retention capacity of the foam, viz., certain physical properties of the enclosed gases determining the kinetics of their partition between the two homogeneous phases and the surfaces and the physical changes of these surfaces due to absorption of the gases. These factors play a dominant role at the formation of the bubbles, and they are of extreme importance when the foam subsides and the bubbles burst, grow or diminish. This very complicated problem is hardly ripe for a detailed discussion. If, however, with Blom (Woch. Brau., 1936, 25; this Journ., 1936, 140) we assume that the subsidence of the foam is mainly due to a growth of bigger foam bubbles at the expense of smaller ones, the bigger ones finally bursting, two physical properties of the enclosed gas must be of primary importance, the rate of diffusion and the solubility of the gases in the liquid forming the film. In Table XII are shown relative values for the two properties of the different gases. As our consideration is entirely qualitative, we may content ourselves with these figures which represent the solubilities in water and the rates of gas diffusion, the values for carbon dioxide taken as a unit.

On comparing these figures with the foam retention capacities (Table XIII) found in the same beer after the formation of foam in the Blom apparatus by means of various gases, it will be seen that carbon dioxide (Geys, Woch. Brau., 1926, 439; this Journ., 1926, 524) and hydrogen, which give the poorest foam retention capacity, also differ from the others with regard to these physical properties, carbon dioxide in possessing by far the greater solubility and hydrogen the greater rate of diffusion. Oxygen, nitrogen and air which, as regards diffusion and solubility, are almost alike, give approximately the same foam retention capacity (cf. Krause, Text Book on the Theory of Malting and Brewing, 217, Copenhagen, 1935).

It is, of course, difficult, if not impossible, to estimate the relative importance of the mentioned physical properties. But, giving both the same weight, by forming their product, figures are actually obtained which —with a single exception—go parallel with the foam retention capacities (cf. Tables XII and XIII).

A corresponding result is obtained by the Carlsberg method, when the foam measurement is taken in samples of the same beer, but filled under different gases. The result of such an experiment will be found in Table XIV.

The variations are not so great as those in Table XIII. This may be accounted for by the fact that whereas pure gases are employed for foam formation by the Blom method the foam in our measurements (Table XIV, Carlsberg method) is formed by means of the carbon dioxide contained in the beer mixed with small quantities of other gases. If the same samples are measured by the Blom method but with foam formation caused by carbon dioxide in all cases, even smaller variations are obtained. The sequence, however, remains the same. It thus appears that even a very small amount of air in the carbon dioxide has a considerable influence on the foam retention capacity. As the foam sub sides gradually the carbon dioxide escapes from the small bubbles into the bigger ones, and the concentration of the other gases hi the former will increase as such gases escape more slowly than the carbon dioxide. Thus, the influence of the small quantities of air originally present will gradually increase with the disappearance (bursting) of the bigger bubbles. This is presumably also the explanation why the foam retention capacity, when measured by the Carlsberg method, is influenced to such a great extent by very small quantities of air. Liters and Moninger (Woch. Brau., 1935, 385; this Journ., 1936, 90) attribute the cause of the differences in the stability of foam formed by means of air and foam formed by means of carbon dioxide to a fall in the surface tension brought about by an effect of the carbon dioxide on the weaker acids in the beer. These authors find support of this view in the work of Lottermoser and Baumgürtel (Kolloidchem. Beihefte, 1934, 73), who showed that the surface tensions of the sodium salts of various fatty acids are reduced by carbon dioxide. This is believed to be due to the carbon dioxide liberating the fatty acids which have the effect of diminishing the surface tension. This may be the correct explanation in the case of dilute solutions (0·001–0·1 per cent.) of salts of fatty acids possessing only a slight buffer capacity, but the effect can hardly account for the conditions in the well-buffered beer, the pH of which (about 4·4) lies outside the buffer range of the carbon dioxide.

- The Influence of Carbon Dioxide on the Foam.

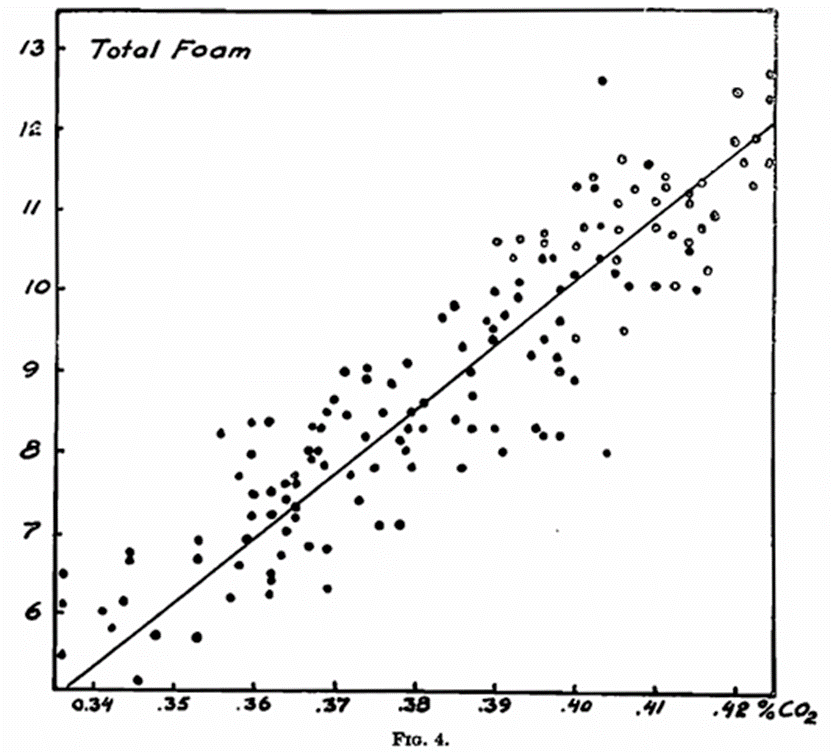

(1) The Head-forming Capacity. — According to the Carlsberg method this property of the foam is expressed by the Total Head, and is a direct function, as is shown in Fig. 4 of the CO2 content in the beer. Each of the 140 points indicates the mean figure for 5-6 bottles of the same sample of beer.

The determination of the head-forming capacity by the Carlsberg method takes place two minutes after the formation of the foam. A more correct result would be obtained were the measuring undertaken immediately after the formation of the foam. For practical reasons this is not possible, the separation between the beer and foam not being sufficiently marked until after the lapse of some time. The total head in the majority of cases may be taken as a measure of the foam-forming capacity. Krauss (Woch. Brau., 1932, 409) contends that a gas content too high or too low is detrimental to the formation of foam, but this does not appear to be the case within the limits shown in Fig. 4.

- The Foam-retention Capacity. —According to Blom the foam-retention capacity bears no relation to the carbon dioxide content of the beer. With the Carlsberg method the position is different, as the formation of the foam itself is based on the gas content of the beer. As will be seen from Fig. 5, in which is recorded the residual foam from the same samples as in Fig. 4, there is no relation between the carbon dioxide content of the beer and the residual head within the limits investigated (0·35–0·42 per cent. CO2.), therefore, the residual head within that range may be taken as expressing the foam-retention capacity. But if the carbon dioxide content falls below a certain limit, not only the total head, but also the residual head is reduced.

The following experiment will illustrate this point: An aluminium cask holding ½ hl. of un-pasteurised Pilsen beer of 10·7 per cent. Balling and another containing Pilsen beer pasteurised were chilled to 1 to 2° C. (35° F.) and placed in a cellar kept at that temperature. After remaining un-disturbed for 24 hours a number of samples were drawn by hand. The casks were then opened to allow the carbon dioxide to diffuse, and samples were again taken after the casks had been left for 48 hours and 96 hours. The first and the last bottle were used for the estimation of the carbon dioxide, and the results are shown in Table XV together with the foam measurements. It will be seen that the falling off in the total head corresponds with that of the carbon dioxide content, whereas the residual head only decreases at the abnormally low carbon dioxide content of about 0·3 per cent.

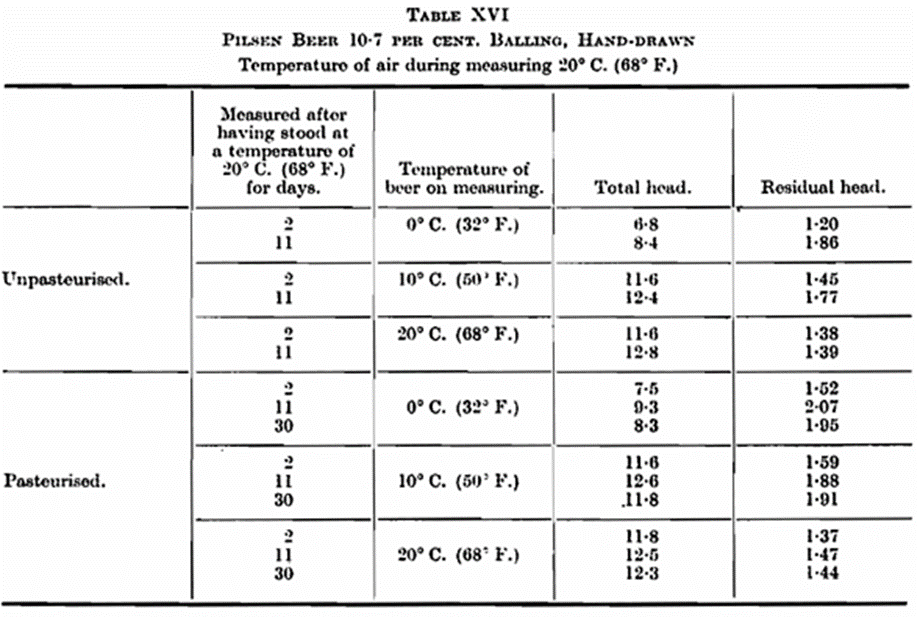

- Influence of Temperature and Time of Storage. —Mention has been made of the influence which the temperature of the beer exercises on the total and residual head. Some results are recorded in Table XVI, which show: (1) The influence of the temperature of the beer on the foam [temperature of the air constant at 20° C. (68° F)]. (2) The influence of period kept on the foam (air temperature constant at 20° C. (68° F.). Each figure in the table is the average of the measurement figures for 6 bottles.

- The temperature of the beer is of funda mental importance for the formation of the foam (total head). Almost double the quantity of foam is formed at 10° C. (50° F.) as at 0° C. (32° P.), whereas the increase of the total head is minimal from 10° C. (50° F.) to 20° C. (68° F.). The position is entirely reversed so far as the foam-retention capacity (residual head) is concerned. Leaving out of account the samples which were measured after having been kept for 48 hours, the residual head is greatest at 0°C. (32° F.), slightly less at 10° C. (50° F.), and consider ably less at 20° C. (68° F.).

- Keeping the beer from 2 to 11 days has improved the foam-retention capacity, but a longer time has not increased the residual head. This is best seen in the case of beer measured at a temperature of 0° C. (32° F.) and 10° C. (50° F.); at 20° C. (68° F.) the difference appears to be insignificant. The total head is much the same, but the variations are less marked.

Silbereisen (Woch. Brau., 1935, 375; this Journ., 1936, 52) considers, on the basis of investigations made by Geys {Woch. Brau., 1927, 146; this Journ., 1927, 305), that the cause of the improvements in the foam is a change in the size of the particles of the colloids. This may be correct, but it is hardly sufficient to explain the considerable improvement of the foam retention capacity. The cause of these changes must be sought for partly in the air content of the beer. Immediately after drawing beer the equilibrium between the air above the beer in the bottle and that dissolved in the beer, will have boon disturbed and will not be established again until the lapse of some time. In other words, during the first few days after drawing, the quantity of air dissolved in the beer will be less than is the case later on, the effect of which will be a rise in the foam retention capacity after drawing has taken place. The cause of the gradual decline as the beer becomes older is to a great extent to be attributed to the fact that part of the dissolved oxygen is consumed by certain constituents of the beer. Table X affords an example of this; 14 days after being drawn the beer contained 4·9 c.c. nitrogen and 1·0 c.c. oxygen, about 4 months later 4·8 c.c. nitrogen and 0·4 c.c. oxygen, and at the same time the residual head had declined from 1·74 to 1·35. The falling off in the head retaining capacity cannot, however, be exclusively attributed to the smaller volume of oxygen, but is, presumably, also due to other changes, possibly connected with oxidation.

These conditions are, however, by no means clear as yet, but the examples mentioned may be regarded as an attempt to indicate certain factors which are of importance in the changes arising in the capacity of the beer on being kept to form retentive foam. Blom (loc. cit.) has observed similar conditions. He found that, after having been left for some days, the foam-retention capacity of pasteurised beer was fairly constant. But in un-pasteurised beer kept at room temperature the foam-retention capacity seems to decline. This was no doubt due to the absorption of the oxygen by the yeast (de Clerck, loc. cit.).

- The Influence of Pasteurisation.—Blom (loc. cit.) records that pasteurisation caused a slight decline in the foam-retention capacity. We can confirm this, although we have found a single exception. As a rule, the reverse is the case when measuring by the Carlsberg method, but also here there are exceptions. These discrepancies may be attributed to the difference in air content and the distribution of the air between the beer and the air space in the neck of the bottle, and also to the age of the beer. From the results recorded in Tables XIII, XV and XVI there would appear to be no fundamental difference between un-pasteurised and pasteurised beer.

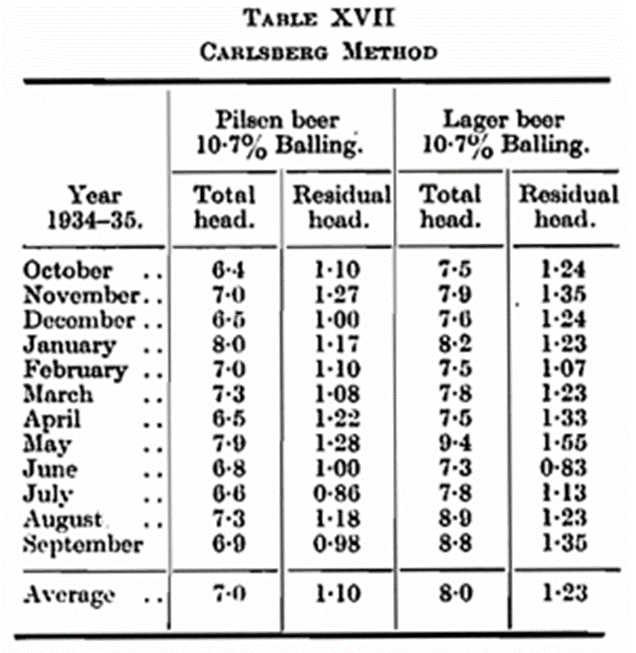

Examples of Application of Method For control purposes in the Carlsberg breweries a suitable number of bottles of each gyle are taken in the course of a month. The samples are raised to a temperature of about 10° C. (50° F.) and the total and residual head measured. Table XVII shows the average monthly figures for Pilsen- and Lager-beer. The reason for the variation in the Lager beer for May and June is obscure. Possibly by the Blom method it could be determined whether the deviations were caused by the beer itself or by the method of collection. Table XVIII shows the foam measuring results of a malting experiment carried out with Binder barley (1933 harvest). Half of this barley was allowed to grow long and the other half short. Each of the different growths were divided into two halves, one of which was high-dried and the other low-dried. Two similar brewings were made of each of the different lots of malt, and care was taken that all eight brewings were carried out in exactly the same manner, so that any differences in the beers could be attributed to the malt. From the results it will be observed that the undergrown malt yielded a beer showing a slightly better foam retention than that possessed by the beer made from the long-grown malt. The malt dried at a low temperature has given a pronounced difference, the foam-retention capacity being distinctly better in the beer produced from the high-dried malt both over and under modified [cf. Raux and Krauss (loc. cit.)].

Agreement between the two brewings of the same malt would appear to be satisfactory, especially when considering the great number of processes the brewings have to pass through before the finished product is turned out. In conclusion, we desire to tender Prof. Dr. S. P. L. Sorensen sincere thanks for the readiness with which he has given valuable advice and assistance during the course of this work.

Summary

Measurements of the foam formation in beers have been carried out by the Blom and Carlsberg methods. As the foam is formed in different ways by the two methods, a direct comparison between the results obtained is not always possible. In such cases where a comparison has been possible, the two methods have on all essential points given similar results. A method is described for the determination of the content of air in beer, whereby it is possible with a fair degree of accuracy to determine the volume of air (oxygen and nitrogen) in beer, in water and mineral waters.

When measured by the Carlsberg method the foam properties of machine-drawn beer vary from bottle to bottle. Such variations arise from the unequal expulsion of the air at the filling of the bottles, the air content of these being of great importance in the head-retaining capacity. Experiments to support this view have been carried out by the Carlsberg and Blom methods. When in the latter other gases than CO2 are introduced (N2, O2, H2 and air) characteristic changes in the foam constant are observed. An attempt has been made to account for these by taking into consideration the different rates of diffusion and solubility of the gases. A similar explanation has tentatively been applied to the corresponding phenomena observed. by the Carlsberg method. On the basis of a large number of measurements carried out by the Carlsberg method it has been demonstrated that the head forming capacity of the beer is a linear function of its carbon dioxide content. The foam-retention capacity is independent of this, provided it lies between 0·35 and 0·42 per cent.

When kept in bottles the beer changes, its foam-retention capacity being improved considerably. After the lapse of about 10 days this improvement ceases, and after a long time of storage its foam-retention capacity shows a slight decline. The possible connection between these changes and the presence of air in the beer is pointed out. Pasteurisation only affects the foam very slightly.

Research Laboratory,

Carlsberg Breweries, Copenhagen.