ON THE FUNCTION OF WORT FLOCCULUM IN AFFECTING

ATTENUATION AND YEAST BEHAVIOUR

By L. R. Bishop, M.A., Ph.D. and W. A. Whitley (1938)

General Method.—Most of the experiments in the following papers were made by the method of laboratory brewing outlined below.

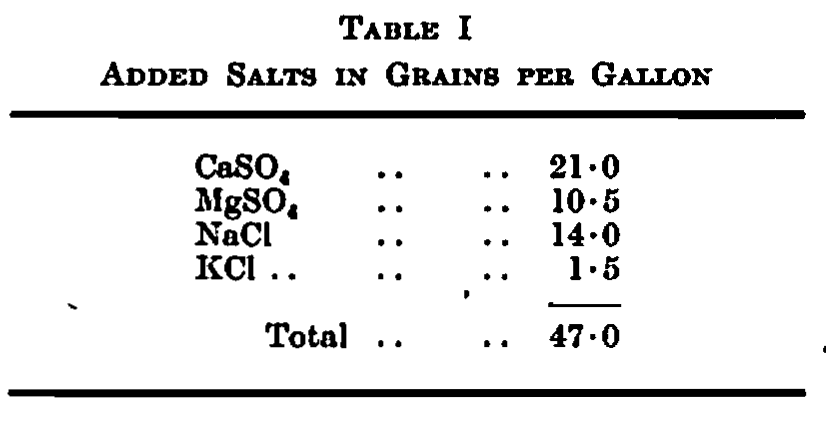

The water used for brewing was Birmingham supply which contains 3-0 grains per gallon of solid matter. To this was added a standard addition of the salts in Table I.

For a few of the early experiments a mixture of English and Indian malt was used which, however, gave a wort with too high a proportion of fermentable matter. There after a standard all-malt grist was employed consisting of three-quarters English and one-quarter Californian malt. A supply of Kentish hops was used in the copper and for dry-hopping.

The Institute’s experimental brewery was used (see this Journ., 1935, 423) for studies of variations in brewing conditions. For many of the experiments a standard wort was needed in order to compare the behaviour of different yeasts; for this purpose a bulk of hopped wort was prepared and divided amongst the respective fermentation vessels. As the result of careful stirring, equal amounts of wort flocculum were present in each vessel.

The fermentation vessels were tall cylindrical “Thermos” vessels shown in Fig. 1. The tall shape caused the yeast to rise as in the brewery, while the vacuum jacket retained the heat of fermentation so that the temperature followed the normal brewery cycle. Aluminium cones were fitted on the top of the vessels during the early stages of fermentation to retain the rocky and yeasty heads. The cones were pre-treated to form a resistant oxide film on the surface in order to prevent the metal from coming in contact with the beer. The refrigerator and all subsequent parts coming into contact with the wort were sterilised with 70 per cent, alcohol and washed with distilled water immediately before use.

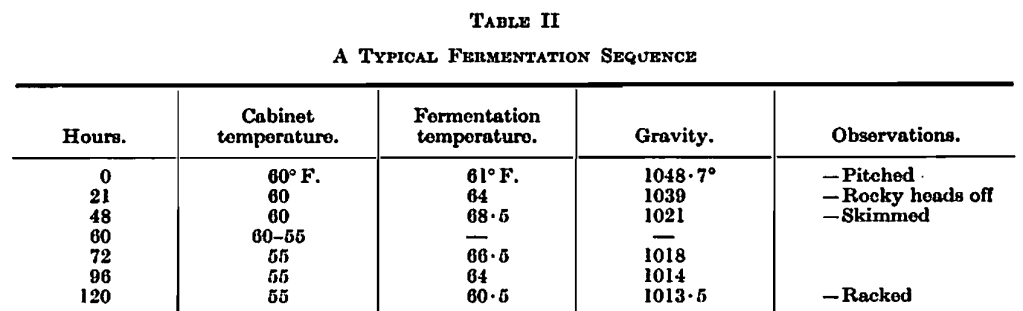

The vessels stood in a thermostatically controlled cabinet. The exact temperature of the wort at pitching and of the fermentation cabinet were varied to suit the gravity of the wort to be fermented. The following is a typical example of a fermentation in the gravity range 1045°-1065°. These fermentations were not roused.

When it was desired to compare the flavours of beers they were racked off into 2-litre aspirators and stored in a cabinet maintained at 55° F. They remained here for fourteen days under carbon dioxide pressure, maintained at 8 lb. During this time they were dry-hopped and fined. At the end they were drawn off into bottles through a coarse filter to retain particles of finings. After one week and three weeks’ storage in bottle, the beers were sampled blind by each taster independently and in an order decided by lot.

The yeast (D) used in most of the experiments was selected as one which did not attenuate well, in order to throw into relief the factors affecting attenuation. The pitching rate was, in the earlier experiments, 2 lb. per barrel of moist yeast, equivalent to 1½ lb. per barrel of pressed yeast. In later experiments the rate was reduced to l½ lb. of moist yeast per barrel (equivalent to 4·17 grms. Per litre).

The course of fermentation was followed in all cases by observations of temperature and gravity similar to those in the example above.

At the end, the weights of top and sedimentary yeast were determined by weighing, after centrifuging under standard conditions. The weights are given throughout as grams of moist yeast per litre of wort.

In later experiments the amount of yeast in suspension was determined nephelometrically by the apparatus described by Thome and one of us (see this Journ., 1936, 15).

In many experiments the total and fine turbidities of the worts at pitching were determined by the Zeiss nephelometer and the readings given in the paper are percentages on this instrument, using a 2·5 mm. cell and the green filter LII. The standard body read 86 per cent. ± 1° (ibid.). The fine turbidity was taken as that which passed a No. 4 Whatman filter-paper. Blanks on the apparatus were determined with distilled water.

The worts had the following composition which may be regarded as normal in brewing:

The wort nitrogen (permanently soluble nitrogen as a percentage of wort solids, using the factor 3·86) was for the brewery worts ·71.

The [ɑ]D of the boiled first wort was 116° ± 1. The attenuation limit of the beers was determined in most experiments by shaking 100 c.c. of the beer with 0·5 grm. of yeast in a 250 c.c. conical flask closed with a stopper and mercury seal as in the forcing test; this prevented appreciable loss of alcohol. The shaking gave a continuous rotary swirl sufficient to keep the yeast in suspension.

The flasks were maintained at 70° F. for 48 hours, or, if the beers were not well attenuated first, for longer periods until the gravity remained constant. This gave 1007·8° as the attenuation limit of the standard wort at 1050° original gravity.

The pH figures were determined by the glass electrode. At each stage they were close to those for large-scale brewing, as is shown by the following specimen result:—

Mash tun Hopped

Liquor wort wort Beer

pH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6·77 5·20 4·04 4·10

SEDIMENT ACTION

It appeared from work to be described later that fermentation difficulties due to shortage of assimilable nitrogen were most likely to occur in low-gravity worts or those with a high percentage of substitutes. So in searching for other causes of fermentation trouble we first avoided these conditions and used all malt worts of a gravity around 1050°.

In Part I a description is given of the action of sedimentary particles in fermentation as it can be observed under the microscope, and it was clearly necessary to see if this striking behaviour led to effects which could be observed in the brewery.

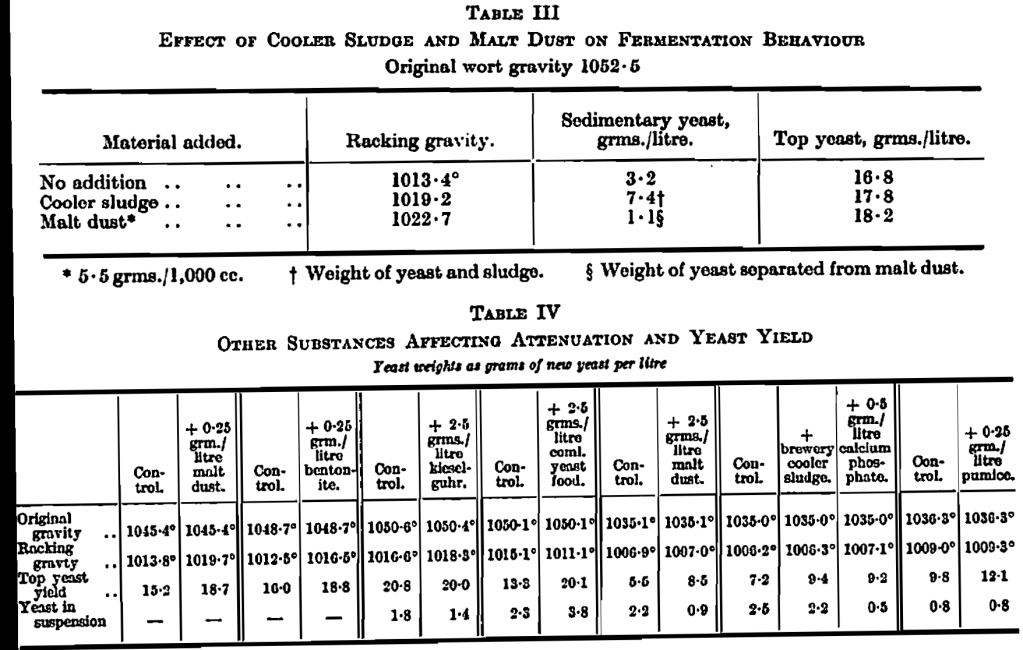

Our first experiment showed definite effects on fermentation resulting from the addition of sterilised malt dust (i.e., dust collected from the bottom of malt containers and sterilised by boiling in water) and of cooler sludge. The result of these additions was a larger yield of yeast at the top of the fermentation vessel, less at the bottom and a less complete attenuation of the wort as is shown in Table III.

Further work given in Table IV confirmed these findings and extended the results by showing that some other substances acted in a similar way. It will be seen that cooler sludge, malt dust, pumice, bentonite (a complex aluminium silicate) and calcium phosphate all acted in a similar way.

That is, they:—

(a) Increased the top-yeast yield;

(b) Increased the racking gravity;

(c) Decreased the yeast in suspension and

(d) Where it could be measured it was found that the sedimentary yeast was reduced.

For convenience we shall throughout the paper refer to this combined set of actions as “sediment action.”

Of the other substances tested, kieselguhr did not show a marked action and a commercial yeast food showed the increased top yeast yield, but at the same time, differed from the rest in giving a lower racking gravity and more turbid matter in the beer at racking. The sediment action on racking gravity was not nearly so marked with worts of original gravity 1035° as with those of 1050°.

The conclusion arrived at was that cooler sludge and the other substances tested, cause yeast to behave in this way, for the reasons advanced in Part I.

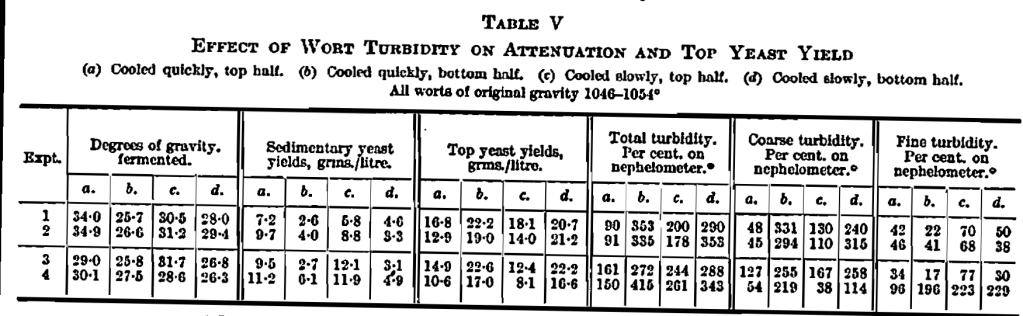

The Importance of Coarse Turbidity.—The next point tested was whether the turbidity, “break” or flocculum formed on the refrigerator behaves in a similar way. These tests were devised to see further if any difference could be found between the action of the two types of turbidity into which wort flocculum may be divided—the coarse floe which settles to the bottom and the fine turbidity which remains in suspension. The work of Clendinnen (this Jonrn., 1936, 567) has shown that the proportions of coarse and fine flocculum can be controlled by the rate of cooling, so experiments were made to obtain an idea of the relative importance of coarse and fine turbidity in their effects on attenuation.

Two portions of wort from the hop-back were cooled differently. One was cooled quickly giving a coarse flocculum while the other was cooled slowly giving a fine flocculum. These were collected sterile and allowed to stand overnight so that the coarse turbidity in each had settled into the bottom portion. The top half of each was then siphoned off, giving four worts differing from one another only in the amount of turbidity in each and whether it was in a coarse or fine state, or both. These turbidities were measured as percentages on the Zeiss nephelometer as described on p. 74. The worts were then fermented under comparable conditions. The experiment was repeated four times with varied methods of cooling. Certain aspects of the results have already been discussed by us (this Journ., 1936, 569, Table IV and text) and the full results are set out here in Table V.

Experiments 1 (a) and 1 (b) may be taken as extreme cases, since they have coarse turbidities of 48 and 331 respectively. The fine turbidities of each were small in amount, being 42 and 22, respectively. 1 (a) attenuated from 1048·5° to 1014·5°, while 1(b) attenuated from 1048·5° to 1022·8°. Since they both came from the same portion of wort whose coarse turbidity was settled into the bottom half by standing [1 (b)], this must constitute the only possible difference between them, and so be the cause of the remarkable difference in racking gravity. The yeast yields show a similar set of differences—the outcrop from 1 (a) was 16·8 grms. and from 1 (6), 22·2 grms. per litre. The sedimentary yeast in 1 (a) was 7·2 grms. and in 1 (b) 2·6 grms., and it must be remembered that this latter figure is high by the extra weight of moist turbid matter included.

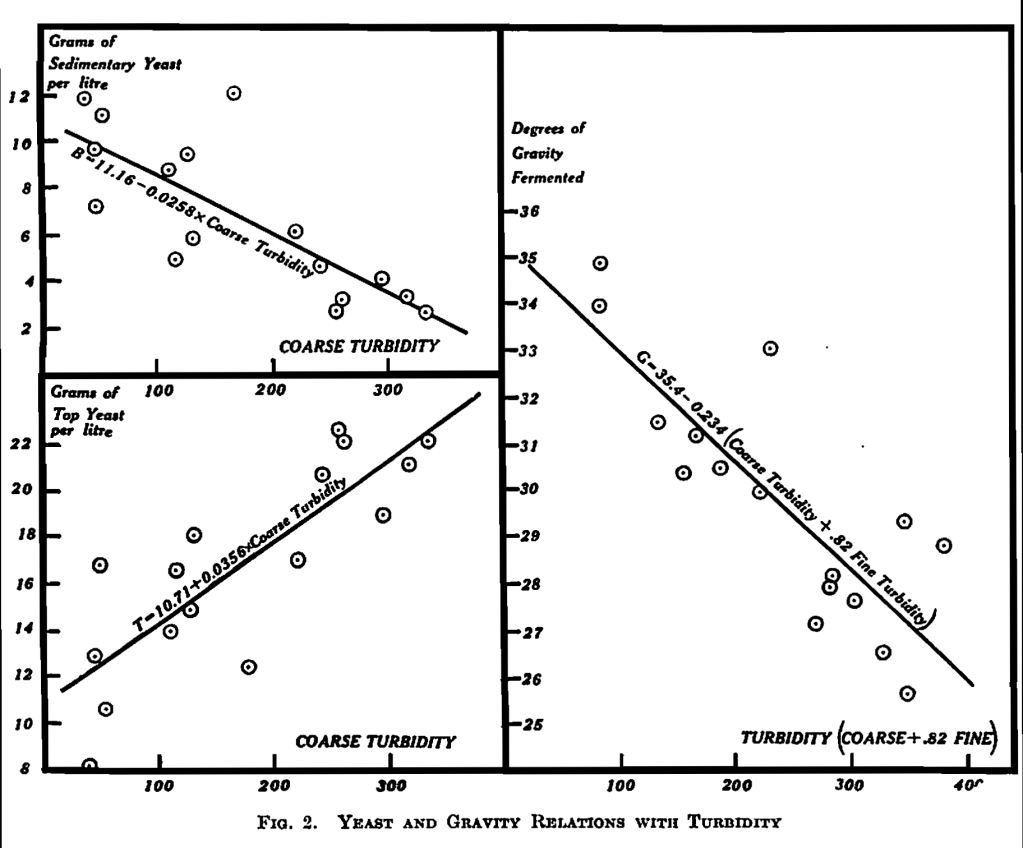

Similarly the effect of fine turbid matter may be followed by taking 4 (a) and 4 (c) as extreme samples. In both there is a low coarse turbidity (54 and 38 respectively) but the fine turbidity is 96 in 4 (a) and 223 in 4 (c). 4 (a) attenuated from 1053·5° to 1023·4° and 4 (c) from 1053·5° to 1024·9°, giving only a slightly reduced fermentation with more turbidity. The yeast behaves as though no turbidity were present; that is there is a very large quantity of sedimentary yeast (11·2 and 11·9 grins, respectively) and the top yeast is correspondingly low in both cases (10·6 and 8·1 grms.). The fermentation results when carefully studied show throughout a fairly close relation with the amount of coarse turbidity. The more coarse turbidity there is, the smaller is the amount of sedimentary yeast and the greater is the amount at the top.

A statistical study showed that the effect of fine turbidity on yeast behaviour is not significant but is, if anything, in the opposite direction to that of coarse turbidity. The relative effects of coarse and fine turbidity on attenuation are different from those on yeast, for the statistical study confirms that when there is much coarse turbidity the fermentation of the wort is checked and there is a similar though smaller effect from fine turbidity.

The significant relations are plotted in Fig. 2. The fall in gravity in experiments 1 and 2 tended to be rather more than in experiments 3 and 4, as the latter were done in vessels rather smaller than the standard size. The smaller vessels were used, since they were provided with “observation windows” through which the behaviour of yeast and turbidity could be watched, as is explained in Part I.

Sediment Effects at Different Gravities.—

F. Windisch (Woch. Brau., 1929, 46, 326 and 337; this Journ., 1929, 505) has shown that, with Continental bottom fermentations, wort sediment stimulates the fermentation markedly. At first sight this appears to contradict the finding that our fermentations were checked by the presence of sediment. However, the studies made in Part I explain how both these effects could be found. The suggested explanation is that, in the slow bottom fermentation, the stirring up of yeast by sediment volcanoes on the bottom is beneficial in leading to greater fermentation; but, with top fermentation the temperatures are higher and the fermentation rate is so great that the numerous bubbles carry the yeast out to the top and check the fermentation.

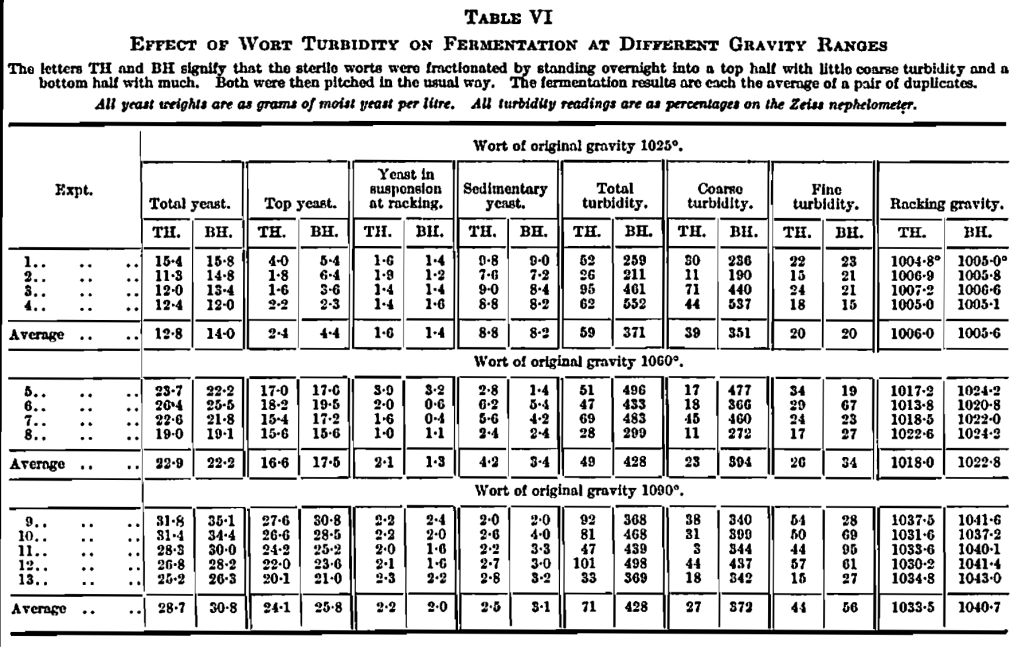

This applied to worts of a gravity around 1050°. The studies were, therefore, extended to other gravity ranges and the same principles were found to apply, but their manifestations were found to vary. The results are given in Table VI. The worts were cooled quickly to give a high proportion of coarse turbidity which, by standing, was settled into the bottom half. So that throughout, the comparison is between slight turbidity in the top half portion (TH) and much coarse turbidity in the bottom half portion (BH). (See photograph, Fig. 5.)

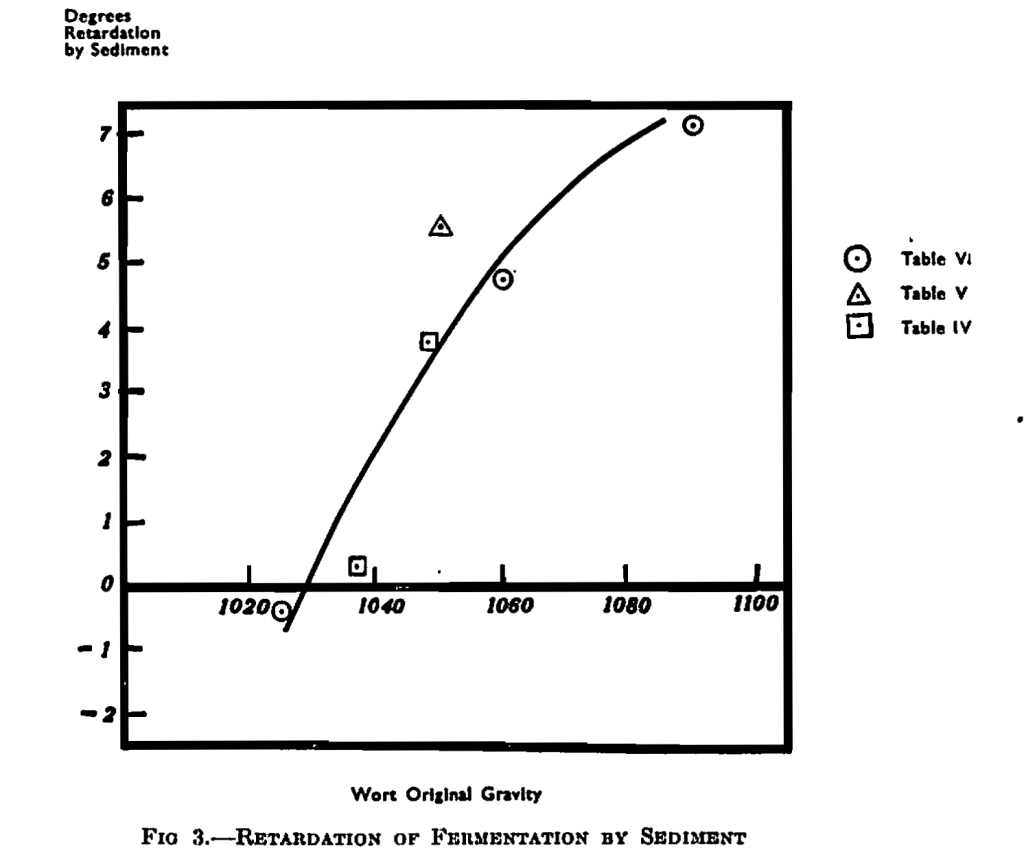

The effect of sediment at the different gravities on the extent of fermentation is interesting, and is best seen in Fig. 3, which is based on Table VI. It would appear that around 1030° original gravity, sediment has no effect on the attenuation and, at original gravities below this, sediment may give increased fermentation. On the other hand, above 1030° original gravity the effect of sediment in checking the fermentation becomes increasingly greater, until at 1090° original gravity it holds up attenuation by 7°. The results obtained with added artificial sediment (Table IV) at 1050° and 1035° (squares in Fig. 3), fall in fairly well with these results from natural sediment, as does the result for natural sediment from Table V (shown by a triangular marking).

These results agree very well with the suggested explanation given above. At low gravities there is an approach to the beneficial effects of sediment found in bottom fermentation; but as the gravity becomes higher the wort is denser and the fermentation more active so that the yeast is more readily carried to the top, especially when assisted by the rapid stream of bubbles from sediment on the bottom.

In turn the yeast yields agree with this view; for there is much sedimentary yeast in the fermentations at 1025° original gravity (over 8 grms. of yeast per litre out of a total of 14 grms.), while at the high gravity, 1090° original gravity, there is a much smaller proportion at the bottom (3 grms, out of a total of 30 grms-.).

It will be seen that, throughout the gravity series, increase of coarse turbidity led to an increase of top-yeast crop of 1 to 2 grms. Per litre. This presumably occurred through more complete washing out of yeast and, in agreement with this, there is less yeast in suspension and less at the bottom in the turbid wort, although these effects are not marked at the very high and very low gravities. In the high gravity wort there actually appears to be more yeast at the bottom of the fermentation with coarse turbidity (BH) but the increase is almost certainly due to the moist turbid matter itself, which has an appreciable effect when such small quantities of yeast are present. The net effect has been to increase the total yeast crop at 1025° and 1090° but, if anything, to decrease the yield at 1060° original gravity.

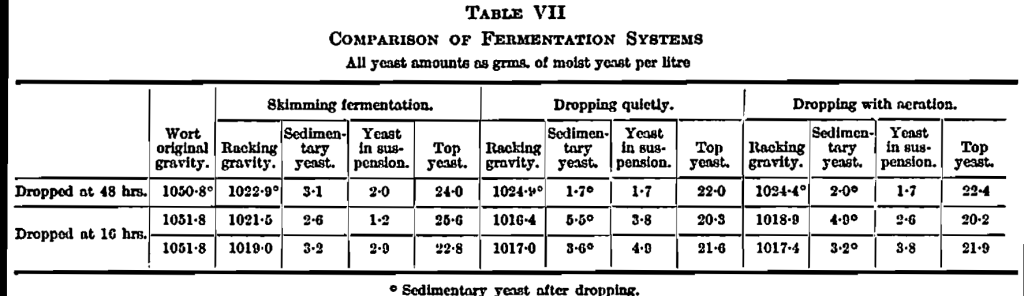

The Dropping System.—Incomplete attenuation is a common fault in brewing and, as it could be remedied in our experiments with the stronger worts by removal of coarse sediment, we considered how such removal might best be achieved in practice. Filtration is difficult and undesirable; and, if worts were allowed to stand and settle on a brewery scale, there would be a danger of foreign infection. So we considered allowing the worts to settle after pitching so that any subsequent infection would be swamped. This amounts to a practice very similar to the dropping system. Here the usual explanation is that dropping is carried out to provide aeration; so that it was necessary to compare (1) dropping with turbulence to give aeration and (2) dropping quietly with care to avoid aeration, with one another, and with (3) a skimming fermentation.

The results of a series of experiments of this type are given in Table VII. In the first experiment the wort was dropped at 48 hours after pitching, that is at the period of active fermentation. The resulting racking gravity was, if anything, rather higher than in the skimming fermentation, whereas with removal of sediment we should have expected it to be lower, but there is some indication of the expected lowering of the yeast outcrop. The failure to get a lower racking gravity was explained as the result of stirring up the coarse turbidity at the most active fermentation stage and this was confirmed by the brown colour of the sedimentary yeast in the second vessel. Consequently in the next two experiments, “dropping” was carried out at 16 hours from pitching and the expected results were obtained, in that brown sediment remained behind at the bottom of the first vessel and the sedimentary yeast in the second vessel was white and nearly free from brown turbid matter. As a result there was less washing out of yeast, more sedimentary yeast and yeast in suspension and, in consequence, the racking gravity was lowered. Dropping with aeration showed no advantage over dropping quietly.

We have been kindly allowed to look through records of comparable brews carried out with straight skimming and with dropping at a particular brewery. There are slight indications of a lower racking gravity with dropping, but no significant differences comparable with ours are to be found and we should explain this as due to the great difference in the depth of the fermenting vessels. In our experiments the sediment has settled out at the end of 16 hours through a distance of 20 in. In the brewery the wort depth in the first vessel is 5 ft. 6 in., and it would appear that the sediment has not time to settle this distance before it is thrown up again by active fermentation, so that no effective removal of turbid matter takes place in vessels of this depth. In our shallow fermentations, on the other hand, this removal of sediment proved very useful in experiments in Part IV (Tables IX and XIII).

Boiling Fermentations.—On the assumption that sediment is the source of evolution of the carbon dioxide bubbles, then if sediment were completely removed, the fermenting wort should become greatly supersaturated with carbon dioxide and any chance evolution would give rise to an extremely vigorous or “boiling” fermentation. This suggestion was, therefore, tested. In two experiments the worts were filtered bright and the pitching yeast was freed from turbid matter by settling in water. The resulting fermentations showed the characteristic weak, bladdery heads of potential boiling fermentations and at the stage of active fermentation the worts were exceedingly supersaturated with gas, but we cannot be sure that the actual appearance of boiling was produced on our small scale. But in a later experiment of a similar type, the wort was filtered cold and pitched with the very active yeast E (see part IV). A real “boiling” was produced by inserting, at the active stage of fermentation, the open end of a tube sealed at the other end. This acted as a centre of rapid evolution of gas from the bottom of the vessel, which in a few minutes broke up the bladdery head and produced a clear surface on which bubbles could be seen bursting in large numbers.

In this connection it is interesting to recall that distillers regularly produce boiling fermentations by high pitching temperatures and by stirring to keep the yeast in suspension, so that the fermentation is very active and the wort becomes supersaturated with carbon dioxide. It may further contribute to this tendency to “boiling” fermentations that, as their worts are not boiled, the sediment may be of a different nature.

Mash Tun and Hop-back Filtration.—So far we have only considered the effects of removal of, and increase in turbidity in the cooled wort, but indications were obtained in the course of the work that removal of the turbidity at the mash tun and hop-back stages led to similar effects. This is indicated in one experiment in which three brews were carried through on the experimental plant. One served as control and in another, 2·5 grms. per litre of malt husks were added to the copper and in the third, 2·5 grms. per litre of starch were added to the copper. This was intended as an imitation of imperfect mash tun filtration and gave “sediment” action, at least on the yeast, similar to that already observed, as is shown in Table VIII.

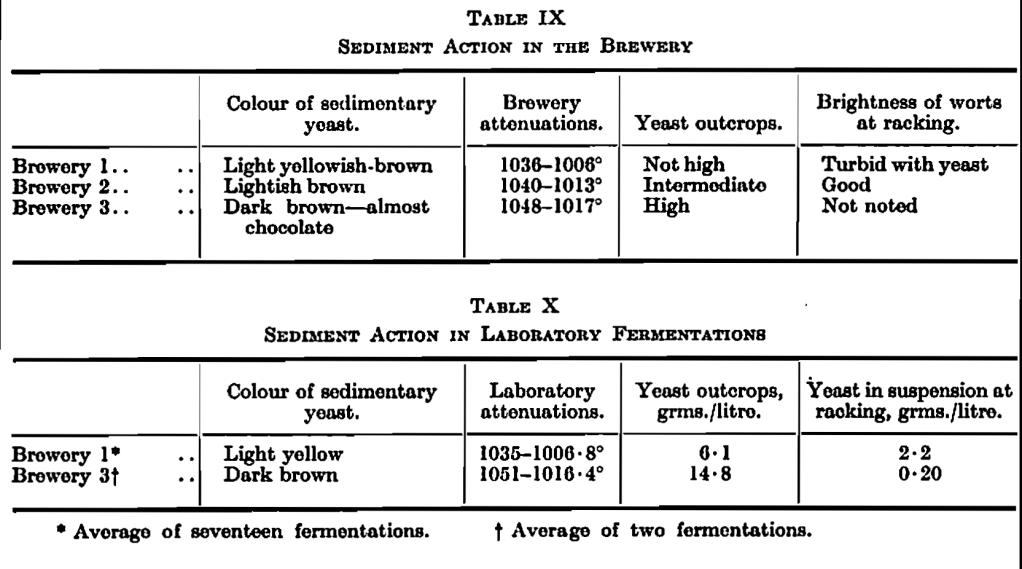

Further and more striking evidence for the effect of mash tun filtration was obtained in the nitrogen-sediment-gravity study which it is hoped to deal with in Part VI, and clear evidence can be seen in Table IX, Part IV.

Diagnosis of Sediment Action in the Brewery. —The tendency of yeast to come to the top readily may be due to the yeast “type” and not to “sediment action.” This is well known and will be shown in Part IV. However, there appears to be a ready way of distinguishing between the two phenomena.

At three breweries we were enabled to study the deposit on the bottom of the fermenting vessel after racking (after scraping aside blanket yeast) and the results suggest confirmation of the “sediment action” hypothesis and an interesting method of its diagnosis. If reference is made to Fig. 1 (Part I), the photograph of the fermentations in two glass vessels shows that in the one with sediment the deposit is dark in colour—most of the yeast has been ” washed out” and dark brown sediment left, while in the other vessel no sediment causes disturbance of the yeast at the bottom, which is whitish in colour. The results given in Table IX suggest that similar observations can be made in breweries. For, in the three we have been kindly enabled to study, much sediment in one was associated with early outcrops and high racking gravities, a second was intermediate and a third with extreme attenuation had little wort sediment and much yeast stayed in suspension. Such a small number of observations cannot, of course, be taken as more than an indication. However, since breweries (1) and (3) were using yeast from the same source, the differences must reside in the wort and the amount of coarse sediment in the bottom of the fermenting vessel is strongly indicated as the cause.

By the further kindness of these two breweries we have been given samples of their worts and yeast and have obtained exactly corresponding effects in our small scale fermentations as is shown in Table X.

It should be added that in all our laboratory fermentations the colour of the sedimentary yeast has been examined and found to agree with these brewery observations.

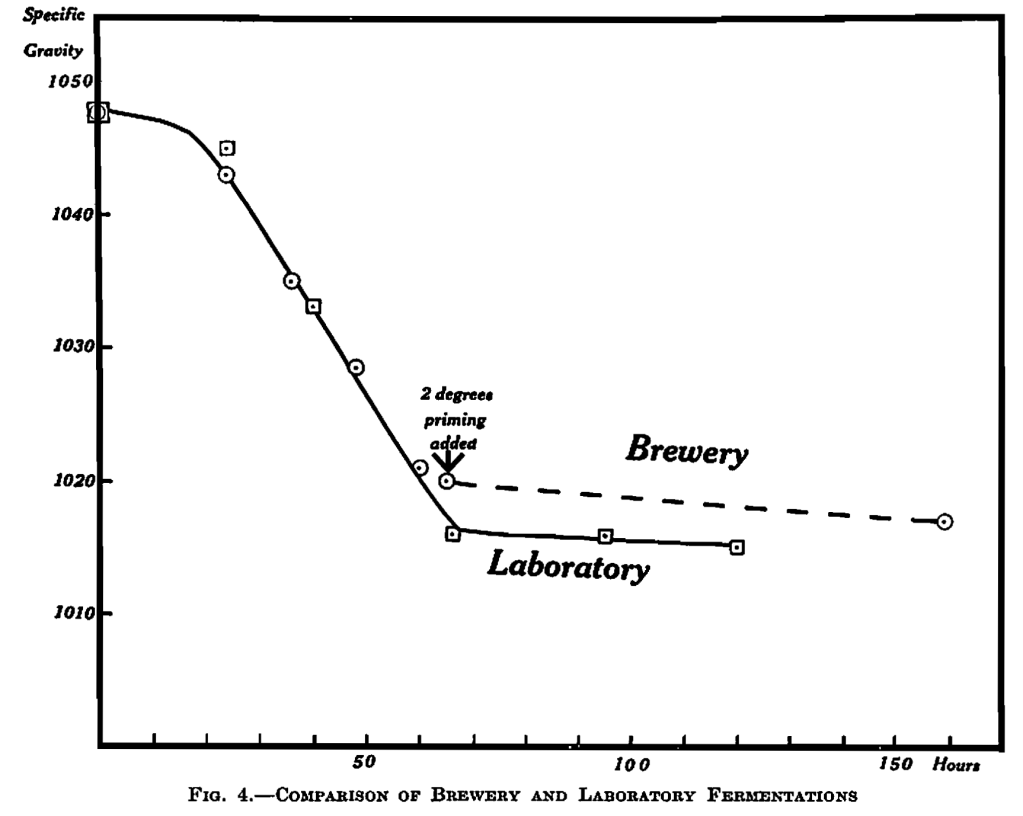

Correspondence of Large-scale and Laboratory Fermentations.—It is perhaps worthwhile pointing out that these comparable results between large-scale and laboratory fermentations, as shown in the comparison of Tables IX and X, is evidence for the validity of conclusions from the latter. Further evidence is provided by a fermentation carried out with wort and yeast from brewery3, where data of the brewery results with this gyle were also very kindly supplied. The results correspond closely as is shown in Fig. 4 except towards the end, when priming was added in the brewery, but not the laboratory fermentations.

Origin of the Action of Sediment.—Having found such a striking effect from the action of sediment, it became necessary to enquire into its origin more closely.

B. Krause (Svenska Bryggareforeningens Mdnadsblad, Part VI, 1936) has dealt with the action of such particles from the standpoint of the phase theory. Clerk Ranken (this Journ., 1927, 70) has described fermentations of sugar solutions in which the addition of peptone, tannic acid, ammonium and sodium phosphates, calcium chloride and ammonium oxalate gave results which correspond with the action we have observed. He also states “large compact heads, slow fermentations and a rapidly brightening fermentation seemed to go together,” but he did not appear to make from this the deduction we have made, i.e., that it is the removal of yeast to the head in the brightening liquid which leads to the slowing down of fermentation.

While the effects we observed are similar, we differ from Ranken in nomenclature. He speaks of the yeasts as coated by the various materials, while, with one exception, we have never been able to find visible coating of yeast. The exceptional case was the dirty black scum thrown up with the rocky head in certain fermentations. In this, yeast could be seen visibly coated with resin particles. Apart from this, no visible coating has been detected in spite of careful search. For instance, fermentations were made with addition of hemoglobin but, though this was precipitated, no hemoglobin colour could be detected on the yeast walls. We have shown that the incomplete fermentation in the presence of natural wort sediment is due mainly to coarse flocculum and there certainly appears to be no coating of yeast by visible particles of wort sediment, as the two photographs in Fig. 5 illustrate.

It should be made clear at this point that we do not deny the possibility of ultramicroscopic coating of yeast; but we do deny the possibility that coating accounts for the effects we have observed resulting from wort turbidity particles visible under the microscope or to the eye. In fact, there can be no such coating for, as we have pointed out, the two separate themselves as far as possible in the fermenting vessel—excess of yeast going to the top, while the coarse turbidity remains at the bottom. In this connection, Ranken’s remarks in the discussion on his paper may be recalled, “He had examined microscopically the yeasts both prior to and after fermentation, and was rather disappointed how little such examination revealed.”

It became important at this stage to find out the nature of the substances acting as centres of bubble evolution. Fermentations with added calcium phosphate had shown that the substance acted in the same way as cooler sludge and refrigerator turbidity as is shown in Table IV. The other tests showed that the action of pumice, malt dust and bentonite was similar. There is little in common chemically between these substances and a physical explanation of their behaviour seems more probable. This is provided in Part I.

However, in considering wort sediment action, it would seem that the effect is, at least in part, connected with the calcium phosphate present. The evidence for this was provided by the examination of the wort from a certain brewery. The turbidity was in a fine state and by reheating and cooling rapidly in the laboratory this was converted to the coarse state. But the result was that the wort still behaved on fermentation as though it contained fine turbidity (or none), that is the yeast remained at the bottom and in suspension, with the result that the racking gravity was low. Addition of cooler sludge from the same brew corrected this, as also did the addition of calcium phosphate— both gave a greater yield of top yeast, less in suspension and at the bottom and a higher racking gravity. An examination of the refrigerator turbidity from this same brewery showed that it contained less calcium, phosphate and iron than normal turbidity; so that evidence was provided that the sediment effect may be, at least in part, connected with the calcium phosphate present.

Silica also forms a fair proportion of the ash of wort sludge (see Enders and Spiegl, Woch. Bran., 1937, 54, 97 and 105; this Journ., 1937, 266) and might well function in a similar manner.

Our thanks are due to a number of breweries for materials and for information which have helped this work considerably.

Summary

(1) In laboratory fermentations the addition of the following substances:—

Sterilised malt dust;

Cooler sludge;

Coarse wort turbidity;

Calcium phosphate;

Pumice; and

Bentonite

gave increased top-yeast yields and racking gravities and decreased yeast in suspension and at the bottom. This is referred to as “sediment action,” since these substances remained at the bottom of the fermenting vessel.

Removal of wort turbidity, or its precipitation in a fine state, produced the opposite effects of:—Decreased top-yeast yields, lower racking gravities and increased yeast in suspension and at the bottom.

(2) The sediment action effects dealt with above apply to worts around 1050° original gravity. The raising of racking gravity as a result of sediment action is even more striking with worts of 1090″ original gravity.

In worts of 1025° original gravity, wort sediment has a slight tendency in the opposite direction, that is to give lower racking gravities; and this tendency is reported to be more striking and definite in Continental bottom fermentation.

Intermediate gravities showed intermediate results.

Throughout the gravity range, sediment increased the top-yeast yield and tended to lower the amount of yeast in suspension.

(3) The sediment action arose from coarse sediment which settled to the bottom of the vessel; while fine sediment had a smaller effect on attenuation and none on outcrop.

(4) On our laboratory scale the dropping system can be used as a means of removing coarse sediment and so increasing the extent of fermentation, but the depth of the usual brewery vessel is probably too great for this effect to show.

(5) Complete removal of sediment gives rise to a boiling fermentation or a tendency to boiling fermentation. The other condition required is a very active fermentation (e.g., from a rapid type of yeast, bottom rousing and a readily fermentable wort).

(6) Removal of turbidity from mash tun wort and, possibly, more effective hop-back filtration have, in increasing the extent of fermentation and yeast in suspension and decreasing outcrop, effects which are similar to removal of turbidity from the refrigerated wort.

(7) The examination of the colour of the sediment on the bottom of the fermenting vessels appears to confirm the sediment action hypothesis, and to suggest a method of diagnosis in the brewery.

(8) It is suggested that the explanation of sediment action is primarily physical rather than chemical, although it may be related in part to the presence of crystals such as calcium phosphate.