THE EFFECT OF ROUSING ON ATTENUATION

AND YEAST BEHAVIOUR

By L. R. Bishop, M.A., Ph.D. and W. A. Whitley (1938)

It was found impossible to omit rousing from a study of the factors governing attenuation, since the interpretation of the other factors is affected by the particular explanation adopted for rousing. A widespread view is that rousing, supplies the extra oxygen needed by yeast to complete growth and attenuation. This will be referred to as the “aeration theory.” The view suggested here is that the yeast in the fermentation head or in the sediment is removed from contact with the main bulk of liquid and that, in consequence, active fermentation is checked. So that on this view, the function of rousing is the mechanical one of returning the yeast to its field of action; a view which will be referred to as the “mechanical theory.” For convenience the different types of rousing have been classified into two groups—bottom rousing and top rousing—according to the layer of yeast which is chiefly affected.

If shortage of oxygen is an important factor, and if the wort is already poor in dissolved oxygen, then aeration of the cold wort before pitching might be expected to have an effect on attenuation. While, if the mechanical explanation holds, pre-aeration should have no effect, and any gas should serve during fermentation. So that the following experiment was carried out. In collecting the wort it was aerated at 180° F. by circulating in the hop back. Thereafter it was carefully protected from aeration during cooling and collection. One half was pitched in this state and the other half had air bubbled through vigorously for half an hour. Each half was pitched into three vessels, one of the three was fermented without rousing, one was roused by air and one by carbon dioxide. The means adopted was that of bubbling the gas through a tube led to the bottom.

The results (Table I) do not favour the idea that cold aeration before pitching increases yeast growth or attenuation. Aeration during fermentation increases attenuation in each case; but, since this is done also by the carbon dioxide, it cannot be due specifically to the action of oxygen. Similarly, while rousing in the brewery is sometimes claimed to be effective by removing carbon dioxide which inhibits yeast growth, it is noteworthy that in our experiments, in each case, the total yeast yield is greater with carbon dioxide rousing. On the other hand, air-rousing has not increased the amount of yeast in suspension at racking as much as carbon dioxide-rousing has, and’ there is more top yeast from air-rousing than from carbon dioxide-rousing. Both these effects may possibly be explained as a result of the great stability of air bubbles which have increased the stability of the top yeast, while the carbon dioxide bubbles have shown a greater tendency to collapse and drop yeast back into the liquid. Such an explanation is in harmony with the results of Blom and of Helm and Richardt on the relative stability of air and CO2 bubbles in the final beer (this Journ., 1937, 251).

It will be recalled that the dropping experiment in Part II (Table VII) also showed no evidence of the value of aeration as a means of supplying oxygen.

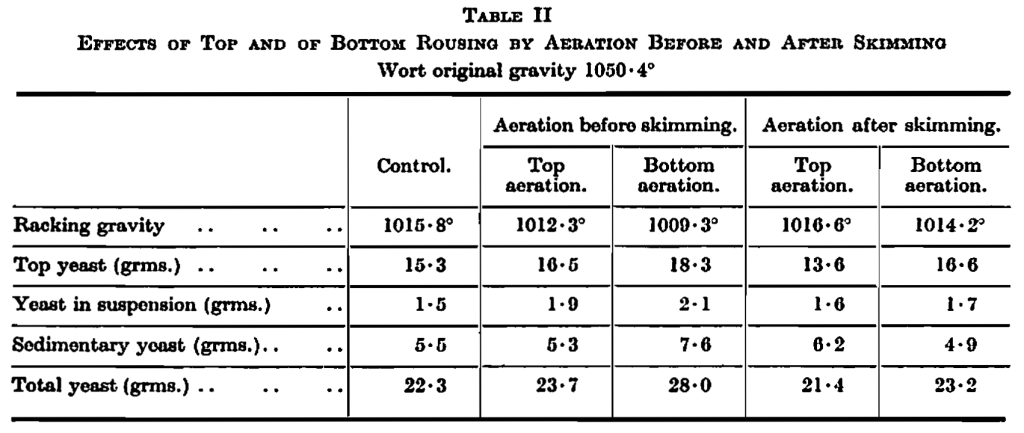

The next experiment (Table II) was a comparative test of the different methods of rousing and of their effects at different periods in the fermentation. Air was used throughout for rousing. The top rousing was by an ejector type of blower discharging through a swansneck over the surface of the fermentation. Bottom aeration was effected by a plain tube, which is satisfactory in the narrow vessels used. The control fermentation was not roused.

From the results it will be seen that bottom aeration before skimming is most effective in producing a lower-racking gravity and that it gives most yeast in suspension at racking. Top rousing before skimming is next in effectiveness. On the aeration theory, aeration after skimming might be expected to be beneficial in giving a lower racking gravity, but no effect was found. On the mechanical theory this is understandable because there was no yeast at the top to rouse in. Bottom rousing after skimming still produced a lowering of the racking gravity, which is in accordance with the mechanical theory, as there is still yeast available to stir into suspension. The effect of bottom rousing on the racking gravity is not as great after skimming as before. This again would be expected on the mechanical theory since rousing the sedimentary yeast before skimming would be bound to cause some stirring in of the top yeast also.

The final evidence in favour of the “mechanical” theory of rousing was obtained by mechanically stirring in the top yeast.

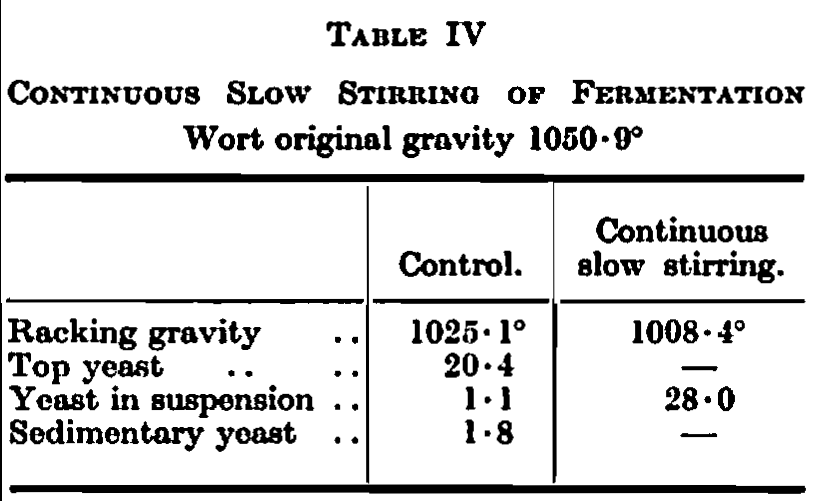

Mechanical rousing was first tried at infrequent intervals corresponding to the times of gas rousing. This was not very effective, as will be seen in Table III, and no doubt accounts for the introduction of the aeration hypothesis. Stirring by gas appears to be more effective in reducing racking gravity and it is proposed to study the matter further. However, mere mechanical agitation if sufficiently prolonged will cause the yeast to ferment the wort as far as it will go (see Table XIV, Part IV). An experiment in the usual “Thermos” fermentation vessels also showed that mechanical stirring alone is sufficient to increase considerably the extent of fermentation. For this experiment (Table IV) the racking gravity was 1008·4° compared with 1025·1° for the control. In this experiment a vertical stirrer of glass was revolved once in every one and a half seconds to keep the yeast in suspension. This was sufficiently slow to avoid turbulence and the introduction of air. The two places where yeast escapes from suspension are in the head and in the sediment. So the stirrer had a glass framework to revolve in and break up the bubbles in the head and a rubber scraper revolving over the bottom.

One point which may be noted is that, throughout the experiments, rousing has resulted in somewhat greater amounts of yeast in suspension at racking.

Discussion

It has, in the past, been claimed that the oxygen of the air supplied in rousing is necessary for greater yeast growth and attenuation. Although such an effect may be found on a large-scale brew, we can find no evidence of such a specific effect of oxygen. One defect of the older experiments claiming a shortage of oxygen in wort is that they were based on “water brews” (that is on test brews in which water was substituted for wort) since it was then not possible to measure the available oxygen in wort. The position has now entirely changed for the modern “rH” method shows the available oxygen in wort to be distinctly greater than that which can be dissolved physically in an equal volume of water. Thus, the old argument ceases to have force. In fact, the modern results may before long lead to the opposite idea, namely to the need for avoiding all aeration during and after fermentation, so that the “rH” may fall low enough to avoid danger from a number of types of brewery infection and from “pasteurization flavours.”

Summary

Tests suggest that, on the present experimental scale, the direct effect of rousing on fermentation is due to the mechanical stirring of the yeast into suspension where it ferments actively. The stirring can be done by air, carbon dioxide or mechanical means.