THE EFFECT OF YEAST TYPE ON ATTENUATION AND YEAST BEHAVIOUR

By L. R. Bishop and W. A. Whitley (1938)

While it is known that fermentation difficulties may arise from the composition of the worts, it is obvious also that difficulties may arise from the type of yeast; and, in this connection, the following studies were carried out.

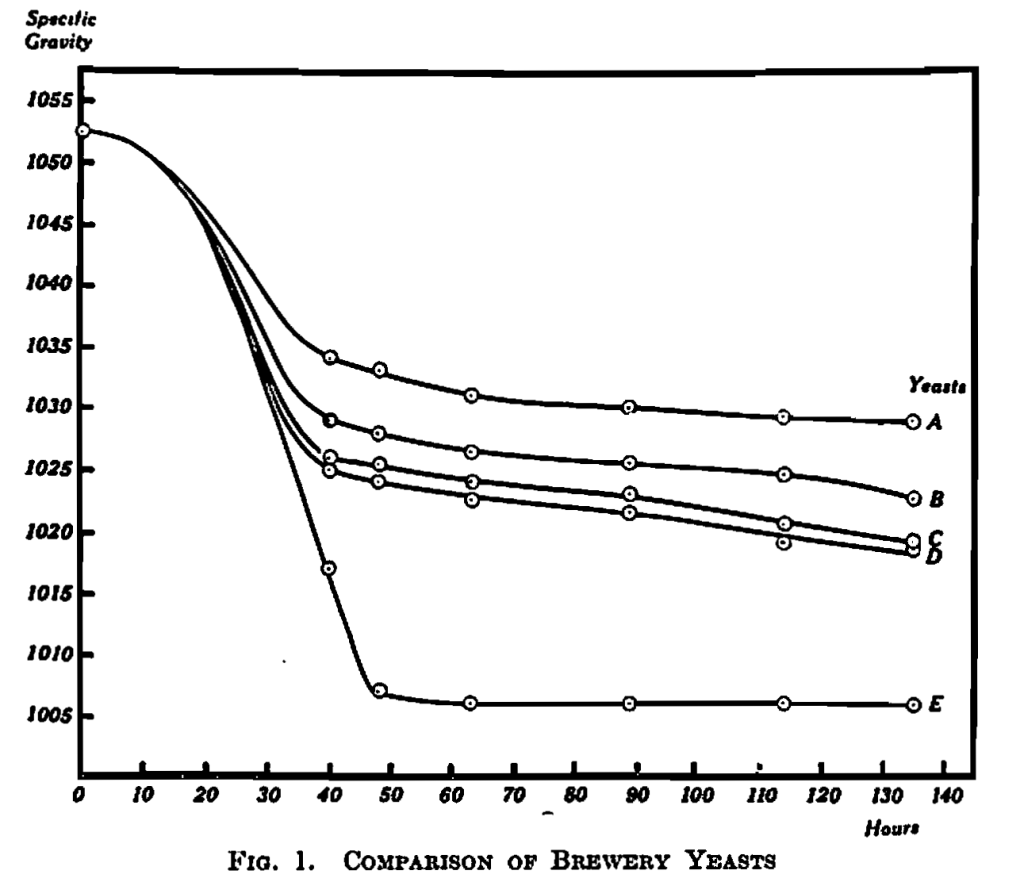

Difference in Yeast Type.—The first experiment was made with the object of comparing the behaviour of five yeasts from different breweries under identical conditions. The course of fermentation was followed as usual by observations of the temperature and gravity. The gravity results are shown in Fig. 1 and the results given in full in Table I. It will be seen from these that yeasts A and B attenuated the wort very incompletely, C and D attenuated moderately and E was strongly attenuative. It is, of course, realised that the differences would not be as striking in practice, since yeasts A, B, C and D came from breweries where rousing is employed, whereas in our experiment the top yeast was carefully skimmed off without disturbance.

This experiment was of some interest and importance as it suggests a way of comparing yeasts in the laboratory for advisory purposes. It was confirmed at the time by repetitions, but it was considered advisable to check it 18 months later by a repetition with new supplies of yeast, and under the more carefully controlled conditions of our later experiments, particularly in taking care to have the same amount of wort flocculum in each vessel. The attenuations do not go quite so far in the second experiment, since the first experiment was made on a wort with an abnormally high percentage of fermentable matter, otherwise closely comparable results were obtained as can be seen in Table II.

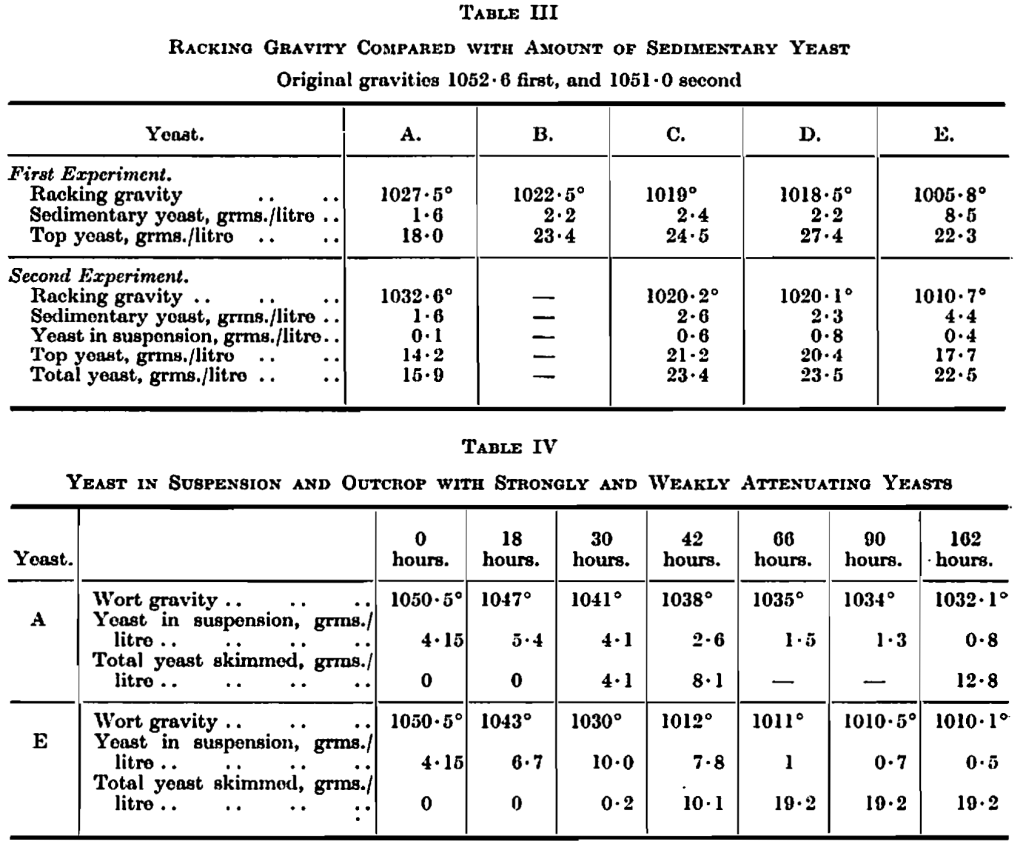

A consideration of the first experiment (Table I) had suggested that sedimentary yeast proportion is a better index of good attenuation than is outcrop and this relation has been supported by the subsequent experiment (Table II). The figures for these two experiments are given together in Table III.

It will be seen that, in both experiments, top-yeast yield is at a maximum for the yeasts giving intermediate racking gravities. The same is true in the second experiment for yeast in suspension and for total yeast. Whereas the sedimentary yeast amount does show an apparent relation to the racking gravity.

Yeast in Suspension Governs the Rate and Extent of Fermentation.—It has already been suggested that yeast in suspension is regarded as the actively fermenting fraction, and sedimentary yeast is regarded as important as a source of yeast in suspension. So that this might explain the correlation observed between sedimentary yeast and attenuation, while the yeast carried to the top is removed from the fermenting zone, unless it is deliberately roused in, and its amount would not be expected to be related directly to the attenuation. The weakly attenuative yeasts, it was noted, threw early outcrops, which suggested that this removed yeast from suspension and so, in fact, accounted for the poor attenuations. Direct measurement in a subsequent experiment proved this point as is shown in Table IV.

It can be seen from this table that there is a striking difference between the two yeasts in the amount of yeast hi suspension from 18 to 42 hours. The average is 4·0 grms. per litre for A, and 8·2 grms. for E. Correspondingly in this period, A has attenuated from 1047° to 1038° (9°) and E has attenuated from 1043° to 1012° (31°). While E skimmed bright, A having attenuated its wort very incompletely, continued to grow and to throw small crops. Several repetitions confirmed this finding and another is shown in Fig. 2.

It is interesting to note from Fig. 2 that, although the yeasts multiply some five or six times the pitching rate, there is never more than two or three times this amount in suspension at any time. This figure also shows very clearly how close the relation is between yeast in suspension and rate of fermentation; with both yeast A and yeast E the yeast-in-suspension curve follows the corresponding rate-of-fermentation curve in shape and in time. For yeast A, both yeast in-suspension and fermentation rate curves suggest 22-23 hours as their maxima; while for yeast E, the maxima occur at 32-35 hours. Almost the whole of the difference in extent of fermentation is due to this ten or twelve hours during which yeast E remains in suspension and multiplies while yeast A is coming out.

Consequently, a weakly attenuative type of yeast, or one which needs rousing to complete attenuation, is regarded as a yeast which is easily carried to the top by carbon dioxide bubbles. The attenuative yeast is regarded as not so easily carried to the top so that is remains in suspension long enough to complete attenuation, and in consequence, the wort being quiescent, a greater proportion is deposited on the bottom; thus accounting for the relation observed earlier between extent of fermentation at racking and amount of sedimentary yeast.

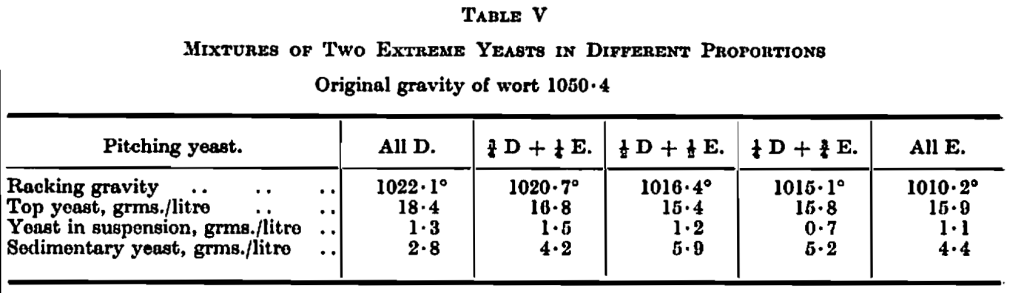

Mixing of Yeasts.—At first sight this hypothesis would suggest that a mixture of half attenuative yeast with half of the weakly attenuative type would be more than proportionately attenuative, as the attenuative half should remain in suspension longer to carry on attenuation. But on test this was not found with a mixture of two extreme yeasts (D and E) in different proportions. For these showed intermediate racking gravities in the proportions in which they were mixed, as is shown in Table V. The sedimentary yeast amounts in the mixed yeasts were higher than might have been expected; so that the usual correlation between sedimentary yeast amount and attenuation was not found.

Segregation of Top Yeast Types

The experiments above had shown that widely different yeast types exist and the questions next arose as to the cause of the differences, and as to how far one type could be converted into another, or separated from it.

Segregation of Top and Sedimentary Yeast. —The first test was made by adding 15 percent, of highly attenuative bottom yeast of the Frohberg type to an ordinary English brewery yeast. This produced a definite increase in the attenuation over the control. Next the top yeast was taken from the Frohberg mixture and used to pitch one portion of wort while the bottom yeast was used to pitch another portion. By successively pitching with top yeast from that inoculated with top, and bottom yeast from that inoculated with bottom, it was found that the top yeast gradually reverted to the less attenuative type and the bottom yeast gradually became more attenuative. A large proportion of Frohberg cells are of a distinctive type, so that it was possible to check, by observation under the microscope, that the major part of the Frohberg yeast was segregated into the bottom fraction. The results are set out in Table VI. It will be seen that, in correlation with its more attenuative character, the sedimentary fraction of the yeast increased its amount and its top yeast amount decreased as the fractionation progressed.

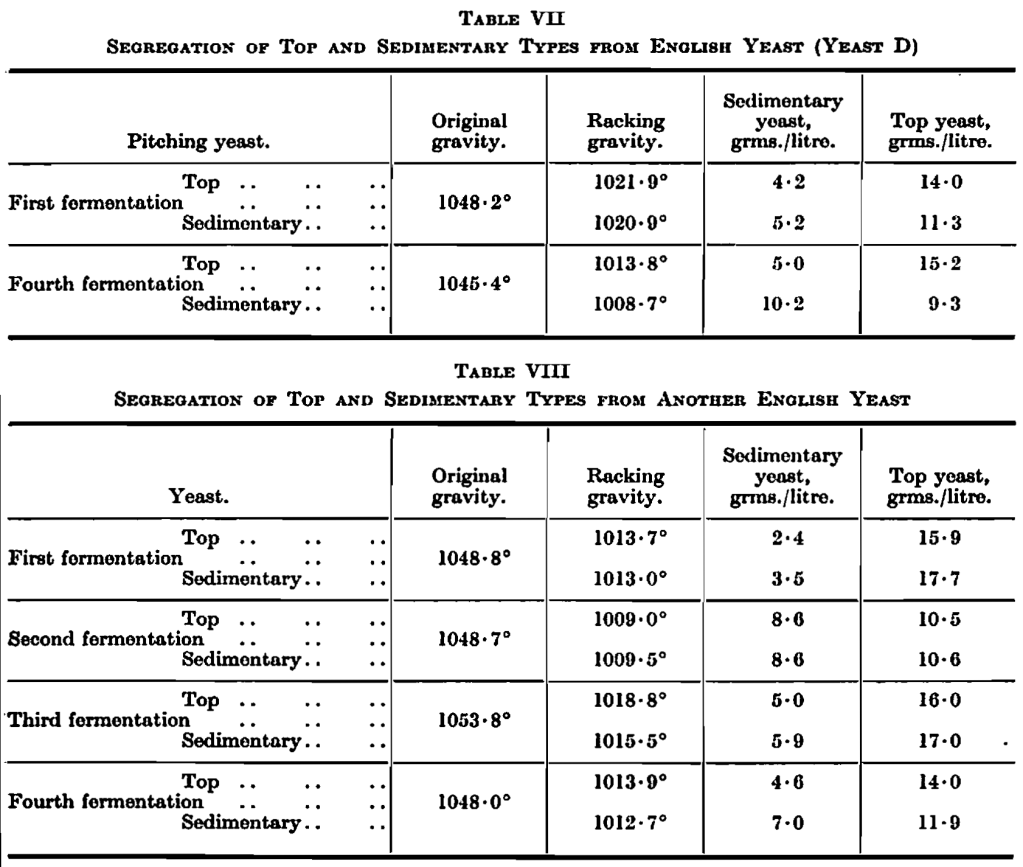

The next experiment was made following the same technique to ascertain if English yeast itself consists of a mixture of types, some of which tend to go to the bottom, while others go to the top. A moderately attenuative brewery yeast was taken and a procedure followed similar to that with the English-Frohberg mixture and a similar, though less striking, result was obtained as set out in Table VII. It mil be seen that the sedimentary yeast fraction increased in amount after its several propagations, while the top yeast amount of this fraction fell. In relation to these changes the sedimentary fraction became distinctly more attenuative.

A yeast of particularly poor attenuative power was then obtained from a brewery suffering severely from the form of yeast weakness associated with incomplete attenuation, and a similar result was obtained as set out in Table VIII.

The results were not so striking as might have been expected. This was followed up and it was found that the difficulty with this brewery lay mainly in the wort rather than the yeast and, since for this experiment we had grown the yeast in wort from its own brewery, we had inherited this difficulty, which was excess of coarse turbidity and is dealt with in Part II.

Segregation by the Dropping System.—This coarse turbidity had, we found, been influencing all our results in the opposite direction to the segregation of yeast effect. We had pitched with sedimentary yeast which is more attenuative, but at the same time an extra amount of coarse sediment had been added which tended to reduce the extent of fermentation.

Since washing the yeast free from sediment might complicate the argument, we decided to remove sediment by using the dropping system, as had been done in Part II. This removal of sediment quickly showed an enormous response and left no doubt of the validity of the segregation as Table IX shows.

This experiment leaves no doubt of the segregation, since after four successive fractionations the racking gravity has fallen from 1020° to 1008°. The fractionation has proceeded in the intermediate (second and third) fermentations but this is not so clearly apparent as the wort had been altered so that even the top fraction of yeast attenuated well. This alteration consisted in greater precautions to prevent turbid matter from leaving the mash tun, especially with the first runnings. This too had a striking effect on the racking gravity and the experiment illustrates how wort composition and yeast type may interact to give the variations observed in practice. In conjunction with the more striking increase in attenuative power of the sedimentary fraction between the first and fourth fermentations there is a striking difference in the yeast behaviour; that is, there is considerably less top yeast and considerably more in suspension and at the bottom. This experiment, therefore, strongly suggests that there are at least two types of yeast intermixed in English brewing yeast, which would account for some of the apparent changes in type which are commonly observed.

We suggest, for instance, that this explains the results given by B. M. Brown (this Journ., 1934, 9). He originally makes a culture from 10-15 yeast cells. Among these we presume there are yeasts of what we should call the sedimentary type. As evidence for this we would quote his statement that the yeasts gave relatively small outcrops. He grows up to brewery scale by putting the whole of the culture into successively larger quantities of wort so that the sedimentary (highly attenuative) forms are preserved. When brewery scale has been reached he reverts to the common practice of selecting the top yeast for pitching. This tends to leave the attenuative forms in the sedimentary yeast end, as he shows, the extent of attenuation progressively declines thereafter.

The flavours of the beers brewed in the laboratory from sedimentary yeast have been found satisfactory and similar to the top yeast except that they appeared rather fuller and, being more attenuated, they were less sweet.

Early and Late Outcrops.—Having demonstrated the segregation of attenuative yeasts in the sediment, the next point was to look for similar differentiation in successive top crops. We have already noted the tendency of the less attenuative yeasts (A and B) to throw early top-crops, and the suggestion appeared to be that these yeasts (by some difference of race or physiology) were easily removed and so fermented less well, unless roused back. Therefore the later crops should consist of yeast less easily removed and so more attenuative. So experiments were carried out, along lines similar to the previous ones; that is, selecting the early top-crops for pitching one fermentation, and then pitching from the early top-crop of this into a subsequent fermentation and so on; likewise carrying the late top crop through successive pitchings in a similar way.

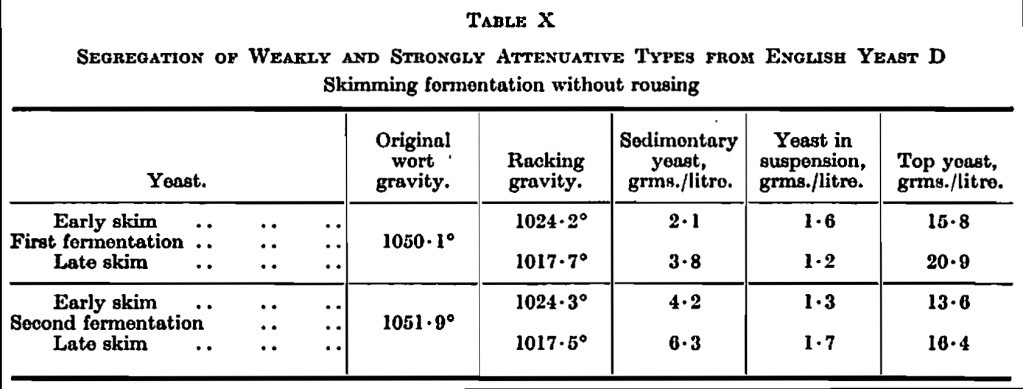

The first experiment was made with yeast D and showed distinct differentiation as is seen in Table X.

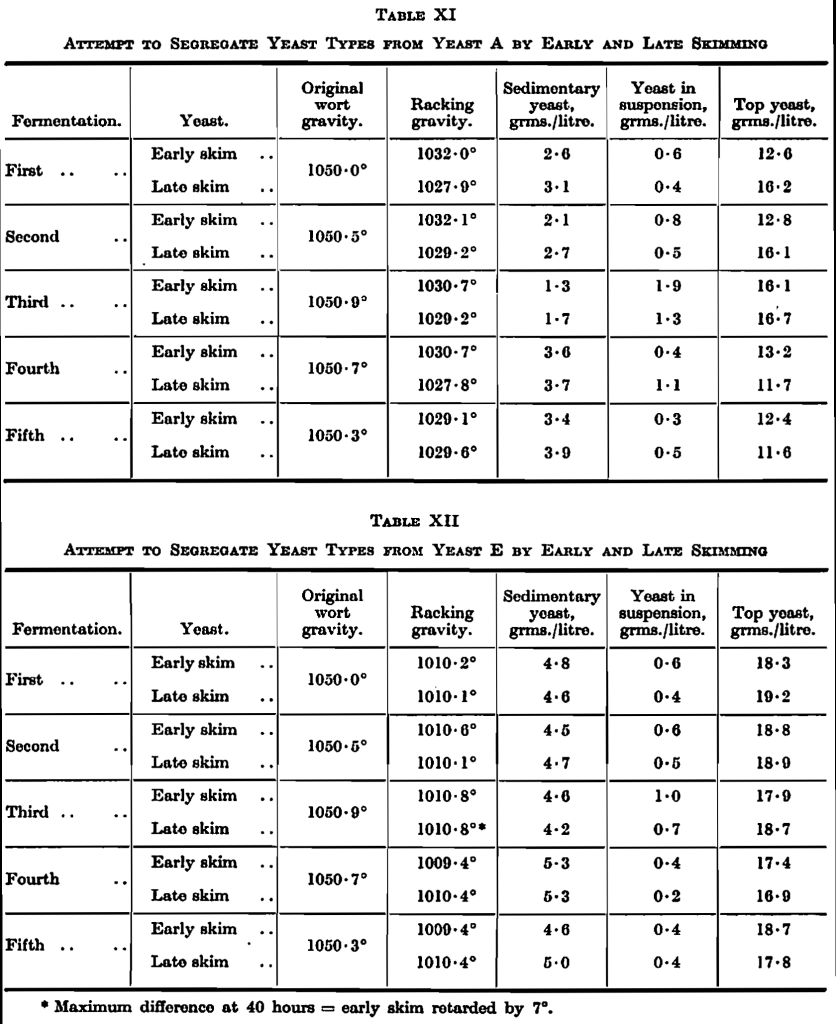

However it was possible that the yeast in this brewery might have been an artificially mixed type. The work therefore was extended by making tests with two more yeasts which were known to have been unchanged at the respective breweries for a considerable number of years. The results wore not very striking as is seen in Tables XI and XII.

The fractionations of yeast A and E were carried on side by side in portions of the same wort and it is interesting to compare the behaviour. In both there is some slight evidence of fractionation in the early stages but this disappears or is reversed in the later ones. It would seem that fractional skimming is not a profitable method with some yeasts though it may serve with others. The two yeasts, as stated, have been carried on for a great many years without change and also represent two extreme types, so that it was possible that they were pure cultures of their respective types. However, a reversion to selection of top and sedimentary types, together with the use of the dropping system, soon showed the composite nature of yeast A, as is shown in Table XIII. The great increase in attenuative power in the bottom fraction, from a racking gravity of 1030° to one of 1010° in four fractionations, is very striking; but it is interesting to note that there is some evidence of a rise of racking gravity with successive top fractions, i.e., from 1030° to 1034°, and this finds some support in earlier results.

The sedimentary yeast amounts increased with the increased attenuativeness of the sedimentary fraction but the top yeast crop, while decreasing intermediately, was finally increased. Probably this was because of the greatly increased growth with the increase in attenuation.

The yeasts examined under the microscope appeared normal and there was no appreciable difference in the proportion of rods which was, if anything, rather smaller in the sedimentary yeasts.

Origin of the Differences in Attenuation by Yeasts.—So far, we have spoken of different types of yeast and have not stated whether the observed differences are attributed to selection of different races or of physiologically distinct varieties of the same race. An attempt is being made to solve this problem. Meanwhile we shall use the non-commital word “types” of yeast. Of these, two main types can be distinguished—the type which tends to come to the top early and so to check fermentation and the type which tends to remain in suspension longer and so to attenuate more and to deposit more yeast on the bottom. Further, we have shown that the brewery yeasts examined consist of mixtures of these types in different proportions and that the proportions can be controlled in our experiments by using top or sedimentary yeast for pitching.

Thus, we have supplied evidence to support the contentions of Moritz (this Journ., 1903, 228): “Yeast as everybody in this room knows is, as we use it in England, a mixture of different varieties of individual cells possessing different properties; and its value, considered as brewing material, depends on the approximate maintenance of that balance.”

It might be thought that tendency to remain in suspension was only part of the truth and that the differences in attenuation were due to differences in the ability of the different yeasts to ferment “malto-dextrins” of higher complexity; but this is not so among the top-fermentation yeasts tested, as the following results show (Table XIV). The four brewery yeasts of Table II were added (at a rate of ½ grm. per 100 cc.) to their respective beers and set on a continuous haker at 70° F. for 100 hours. The flasks were sealed by a mercury seal (as in a forcing test) to prevent appreciable loss of alcohol. At the end of the time the gravities were determined and showed negligible differences.

Consequently we conclude that, within the brewing range of types, yeasts have equal ability to split “malto-dextrins.”

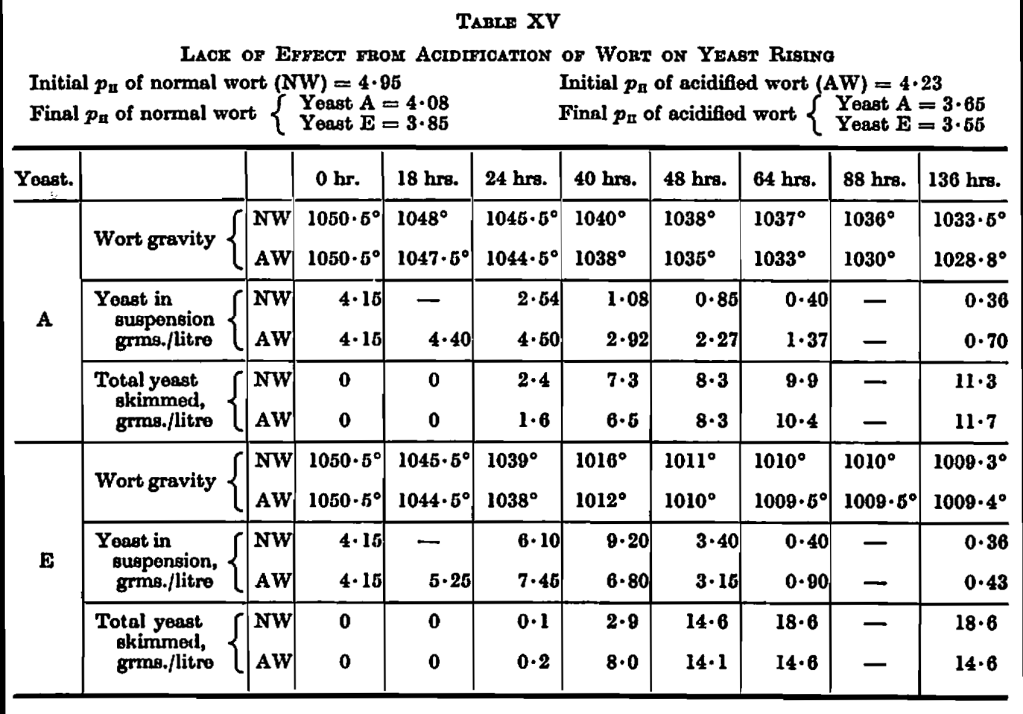

We have as yet no direct evidence as to the origin of the differences in ease of removal of yeast from wort. One hypothesis which readily suggests itself is that yeasts tend to flocculate as the pH falls in fermentation, and that some yeasts flocculate at a higher pH than others. However, to our surprise, the test on this point appeared to give a negative result.

For this test the two extreme yeasts (A and E) were pitched and fractionally skimmed as for the experiment in Table IV. Corresponding fermentations of each were made in which the pH of the wort at pitching had been lowered from pH 4·95 to pH 4·23 by the addition of lactic acid. This gave somewhat better attenuation but did not greatly influence the time at which yeast separation took place. If anything, there is an indication that both yeasts started to come out of suspension sooner from the acid wort; but yeast E still stayed in that all-important six or ten hours longer than yeast A, although, since it fermented faster, yeast E might have been expected to come out sooner.

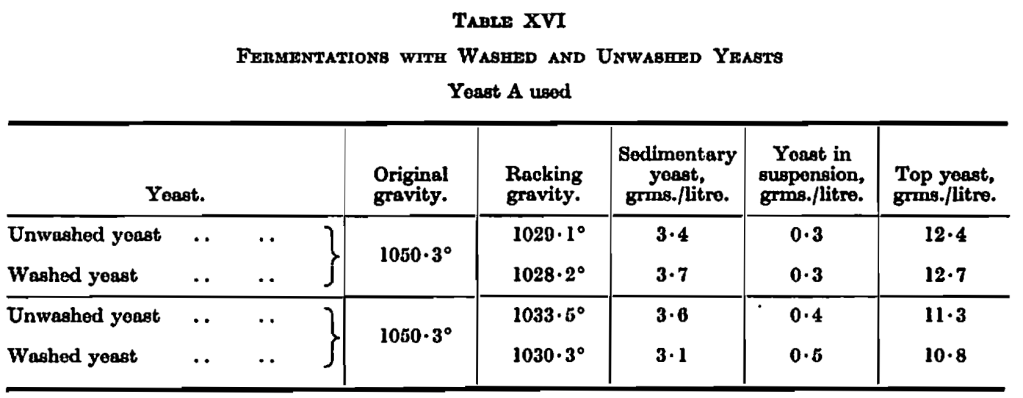

One possible means of altering the yeast type was by washing the yeast before pitching. This was tried at a rate of 10 grms. of yeast to a litre of distilled water. The effects of this on racking gravity, though definite, were not large as is seen in Table XVI.

Summary of Part IV

(1) The top-fermentation brewery yeasts tested were found to consist of mixtures of different types in different proportions. One type tended to come to the top earlier and so gave an incomplete attenuation. The other type tended to remain in suspension longer so that it gave more complete attenuation and more yeast at the bottom.

(2) The greater attenuation of the second type was due, in the main, to the tendency to remain in suspension longer; since, if the yeasts were forced to remain in suspension by continuous shaking, they all attenuated the wort to the same extent.

(3) The proportions of yeast types in the mixture were altered by pitching with top and sedimentary fractions using the dropping system to remove the extra sediment added with the latter.

(4) Some evidence of similar fractionation was obtained by pitching with early and late skimmings of top yeast.

(5) The differences in yeast behaviour are apparently not greatly affected by acidification of the wort or washing the yeast before pitching.