THE EFFECT OF FERMENTATION VESSEL DESIGN

ON ATTENUATION AND YEAST BEHAVIOUR

By L. R. Bishop and W. A. Whitley (1938)

The findings in different Parts of this series suggest three different methods by whichattenuation in the primary fermentation can, in appropriate circumstances, be increased.

These are:—

Removal of coarse wort sediment (Part II).

Rousing the top or sedimentary yeast (Part III).

Selection of attenuative type yeast (Part IV).

On referring to each it will be found that all involve a greater proportion of sedimentary yeast and of yeast in suspension at racking. This is a disadvantage and only one way was found in which we could combine the advantage of complete attenuation with that of low yeast content at racking. This was by vessel design.

The Institute’s experiments on fermentation vessel design began in 1928 with the late Mr. Day’s earliest fermentations. He first of all confirmed, by experiments in tall cylinders, that such a shape is necessary for fermentations on a small scale to give top-yeast proportions which are comparable with those in the brewery. The next stage came when he used tall vacuum flasks (Dewar vessels) to ensure that the heat of fermentation should cause a rise in the fermentation temperature from 58°-60° F. to 68°-69° F. followed by a slow fall back and so to imitate large-scale conditions in a second particular. With these he showed that it was possible to produce beers comparable in flavour with large-scale ones.

Subsequently we have added the refinement of a thermostatically controlled chamber in which the vacuum vessels stand. This provides a means of delicate and even attemperation and has added considerably to the reliability of the results.

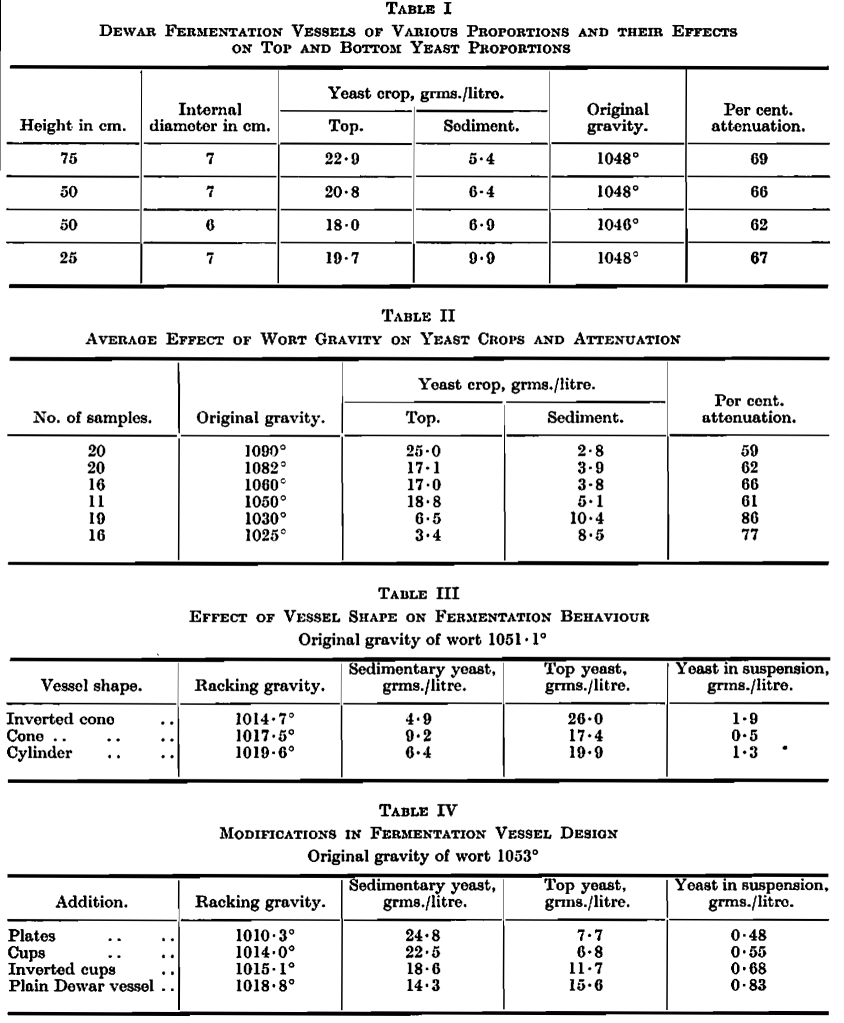

Proportions of Fermentation Vessels.—With the help of this chamber we have experimented with vessels of varying shapes and sizes. Table I, below, summarises the results obtained with Dewar vessels of cylindrical shape but varying dimensions.

The experiments in Table I were done at different times but were all with yeast from a particular brewery and with worts of gravity 1046-1048°. The vessels with a diameter of 7 cm. and height of 50 cm. were found most desirable and were adopted as standard. The conclusion reached was that the size of vessel does not greatly affect the degree of attenuation, but that the proportion of yeast coming to the top depends on the depth of the vessel. This conclusion was supported by comparisons, given in Part II, between brewery and laboratory fermentations; the racking gravities of which compared closely, but the yeast outcrops, though varying correspondingly, were somewhat lower in the laboratory fermentations.

The Effect of Wort Gravity.—The gravity of the wort also affects the top yeast proportion as is shown in Table II, which gives the average results of fermentations at various gravities in the standard vessels. With this, however, the percentage attenuation is altered from incomplete fermentation at high gravities to more complete fermentation at the lower gravities. The greater attenuation and smaller outcrop are marked in the 1025° and the 1030° beers; such an effect is, of course, well known on the brewery scale. Several causes undoubtedly operate in this. In the first place the yeast cells are more easily carried to the top in the denser worts. These also ferment more vigorously, and finally, have a greater amount of sediment which, resulting in a more rapid C02 evolution, from the bottom of the vessel, will give a more vigorous “washing out” of the yeast.

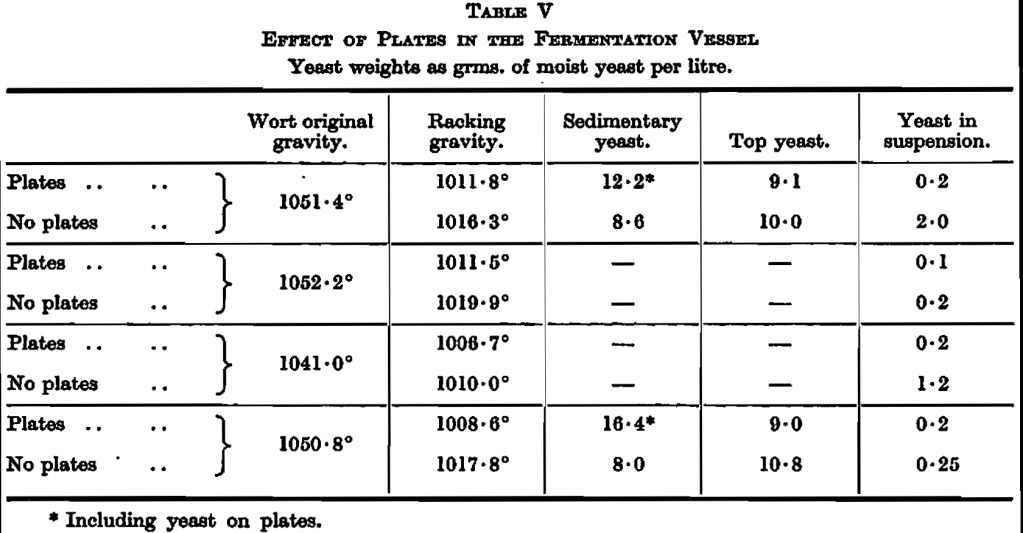

The Effect of Vessel Shape.—Ordinary conical flasks were used in further tests to compare the effects of a cone-shaped vessel and an inverted cone with a cylinder. Since these were not vacuum-jacketed it was necessary to adjust the fermentation cabinet temperature each day to simulate the natural rise and fall of temperature in the vessels. The results are given in Table III and show that the greatest attenuation was obtained with the inverted conical vessel where the top-yeast yield was the greatest. The important factor appeared to be the degree of circulation which was marked in the inverted cone. It was observed that the layer of wort sediment at the apex of the cone continually disengaged gas, which threw the yeast into the wort and it will be seen that the highest proportion of yeast in suspension occurred in the inverted cone. But the conical vessel (not inverted) had the smallest amount of yeast in suspension and yet had attenuated better than the control in a cylinder. The explanation here appeared to be that the base of the cone offered an expanded surface of yeast still actively in contact with wort.

The Effect of Plates.—The need for a greater expanse of surface on which the yeast could settle was supported by experiments with a tier of shallow cups, of inverted cups and of flat plates in the fermentation vessel compared with the plain vessel. The latter gave the poorest attenuation and the flat plates the best. In each case the degree of attenuation was related to the amount of sedimentary yeast (which included that settled on the plates) as is shown in Table IV.

It was found that, in the fermentation vessel, yeast can only settle on a horizontal or slightly sloping surface and this is the reason for the varied amounts of sedimentary yeast on the different types of plates. The inability of yeast to settle on surfaces with only a moderate slope is presumably due to the disturbance by carbon dioxide bubbles which dislodges yeast from such a position.

Proposed New Fermentation Vessel.—For the next development an attempt was made to combine the benefits of plates and of circulation. A pair of large rectangular vessels were used; one served as a control and the other was fitted with a tier of flat plates. These fitted tightly to the sides but allowed free spaces at the ends. They sloped gradually from one end to the other and so induced a gradual circulation of the wort. This had the anticipated effect of increasing the attenuation, while at the same time there was more sedimentary yeast and there was a very low yeast content at racking as is shown in Table V.

The arrangement is indicated diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

In some respects the system bears an analogy to the “self rousing” found in the Burton Union system, for in this also the wort is caused to circulate past the yeast, and the result in both cases is to produce bright, well attenuated beers.

Often in the usual type of fermentation vessel, the yeast has been skimmed and the fermentation has nearly stopped by some sixty hours from pitching, but it is necessary to leave the beer for at least another sixty hours, to settle the yeast, before racking. Using the vessel with plates there is a steady fall in gravity, so that the beer can be racked at the desired attenuation with a sufficiently low content of yeast in suspension.

No doubt practical difficulties might occur in the use of such a vessel but it is considered that the difficulty of cleaning the plates can be overcome by making them removable. The use of an attemperator just below the top surface of the wort should increase the degree of circulation by causing the cooled wort to drop away to the lower end of the plates.

The principle of nearly horizontal surfaces arranged to give circulation can be adapted to suit other arrangements of attemperator.

Summary of Part V

The effect of size and shape of fermentation vessels has been studied. Previous parts have shown the possibility of increasing attenuation by retaining more yeast in suspension. This is a practical disadvantage and it has been found possible to obtain bright worts at racking and greater attenuation by providing a series of sloping plates on which the yeast settles and around which the fermenting wort circulates.