MEETING HELD at the QUEEN’S HOTEL, LEEDS, on Friday, November 27th, 1903

Mr. A. J. Murphy in the Chair,

The following paper was read and discussed:—

Practical Brewing in the South African Colonies.

By J. K. Laurie.

In presenting a paper on this subject before the Institute of Brewing, before which so many able men have dilated on various subjects, I am deeply conscious of the truth of the well-known proverb: “There is nothing new under the sun,” I desire, therefore, at the outset to say that while I do not presume to be able to add much, if anything, to brewing knowledge, from the strictly scientific standpoint, yet I would urge that it is sometimes useful, amid the learned exegesis of specialists, to listen to the humbler pleadings of the ordinary every day brewer. For whilst no one values more highly than I do the work of the laboratory and all it has done for our industry, I still think that it is just possible that practical brewers—by which I mean, in a word, working brewers—may know something worthy of at least passing notice.

I cannot, perhaps, do better than commence by briefly pointing out a few of the great difficulties with which a South African brewer has to contend—difficulties of climate, brewing materials, water, etc.

Take, for example, the following columns of outside temperature extracted from records in my brewing diary.

It will be at once remarked that these are not proportionately balanced, but this is solely accounted for by the prevailing winds. On each of those days the temperature in my fermenting room would probably be from 8—10° less than the outside shade temperature.

Consider next the enormous distance the brewer is from the source of supply of nearly all raw materials; the time these take to arrive; the fear of ordering too much at one time lest they deteriorate; the danger of running short of anything, and a thousand-and-one-other special contingencies always existent to mar the South African brewer’s peace of mind. He can cable, it is true, but cables cost money, and are usually dismissed from the mind of an economic brewer. The best plan is to compile an alphabetical list of every conceivable article used in a brewery, from malt and hops to shives and vent-pegs, apportion the quantity of each to serve for say 2 or 3 months, according to the part of the country in which the brewery is situated, allowing at the same time for such trifles as a boat being wrecked or broken down in mid-ocean, and other ills to which Colonial brewing is heir.

Malt

Malt is shipped in several ways, in galvanized iron tanks, 200 or 400-gallon sizes; in zinc-lined cases holding about a quarter—I say “about” because the Continental standard is not our weight—and in double sacks holding from 3—3½ bushels. The first method looks the best perhaps, but I have seen many tanks come to grief through the rough handling they are subjected to. They are unwieldy cumbersome things, and in spite of their appearance of standing any amount of knocking about, I have known instances when their contents were ruined with rain-water. When empty the tanks are sold at a profit for water-tanks, but the market can easily be glutted with them. Next come discs. It is impossible in South Africa to realise their cost price.

With sacks, however, it is quite different; they are made specially to hold a “mude,” the South African measure for 3 bushels; they are cheapest, easily saleable, and most easily handled, but the most risky in wet weather.

Colonial malt looks very much like Smyrna in appearance, but it is inferior in keeping properties. Its’ one advantage is cheapness, but it is only good enough for making one quality of beer, i.e., the much heard-of beer since the war—”Ticky” beer. This kind of beer must not be despised, for although it only costs a “ticky” (3d.) per large bottle, it is good value and a very appropriate beverage in the warm climate. I myself prefer it to export beers. I shall describe the method of brewing “ticky” later on. Much more malt could be made in the country if the Boer farmers were more accommodating. In the Transvaal they looked skeptically when offered for nothing English barley seed to grow and sell back the product, the brewer’s object being, of course, to secure plumper barley.

The cleaning and grading of the native barley is an essential factor, otherwise sarcina and all sorts of troubles may crop up. The malt was often too highly dried, and this applies to some English supplies imported in sacks, to stand the voyage, whilst better qualities dried on modern kilns in Great Britain were perfectly cured without imparting colour, enabling the brewer to strike at any desirable heat. All this irregularity pointed to one thing which I advocated years ago, but to no purpose—pneumatic makings—which I learn, however, are being extensively installed now. When I first suggested Chilian malt in place of Californian for the best beers, a well-known English maltster remarked that he had never heard of such a thing, and wondered if the brewers at the Cape had lost their reason, but he was agreeable to make the desired quantity at their risk. I wonder how many thousands of quarters his firm has since then produced of the same article?

Hops

Hops were consigned in a manner I could gather at a glance to economise freight, the pockets and bales having been placed under a special hydraulic press and compressed to about 2/3 their usual bulk. A piece of hoop iron is riveted round them like the figure 8 to keep the packages in their place after emerging from the press, and they are carefully wrapped in water-proof tarpaulin. If they arrived without any holes being pierced you could depend on the contents being in fairly good condition, not otherwise. We tried a proportion of our consignments without this extra pressing, and I believe the beers afterwards had a more delicate flavour. Hops direct from the Continent sometimes came neatly and firmly packed in zinc-lined cases.

Sugar

It is true that sugars are easy enough to export if they be of the kind that many, probably most, brewers prefer, namely, invert and dextrin-maltose, but it is a most harassing and difficult task to prevent leakage. The wood of casks shrinks in the hold of the vessel with the heat, they land on the quay in no gentle manner from the cranes, and I would recommend a cooper to be standing ready to tighten up the hoops before the sugar is shipped again for its destination on the wagons or trucks. Tanks are all very well again, but awkward in every way and not free from accidents; the cask is so handy for smaller and suitable quantities to place over the sugar dissolving vessel, and come in for rolling plant.

Yeast

At one time yeast in transit gave rise to much concern and worry. It has been exported in all sorts of ways, but there are two forms which can be wifely relied upon at the present day. One is the method adopted by the British Pure Yeast Co., Ltd, who send out the yeast in 28 lb. tins hermetically sealed, specially prepared for export by Heron’s process, with directions for use on the outside of each tin. The other is Briant’s method, in which the yeast is dried with plaster of Paris into balls about the size of a schoolboy’s marble. Of course, they are sent out by preference in the cold chamber. In either case after breaking up the preparation, adding it to a small quantity of wort and reproducing the yeast again and again, by about the fourth or fifth time the characteristic flavour of the particular product will have been obtained. Ordinary yeast may be conveyed from one part of the colonies to another in cool chamber, 3 or 4 days’ journey, pressed with powdered carbonate of ammonia, mixing ¼ oz. to 1 lb. of yeast well together and pack in ice. Salicylic acid will not kill yeast, but an overdose may affect the first brew. This difficulty can be overcome by washing the yeast in cold water, throwing it over a vacuum tray and drawing the salicylic acid away with the water, leaving the yeast on the cloths above. I prefer this method, and for the purpose of pitching yeast it is much safer than a compressing yeast-press.

Plant

There are many eccentricities, as I should call it now-a-days, in brewing plant. There is the hot liquor tank for a start: I should term him an eccentric old “man.” It often happens that a fairly large concern possesses only one, and that I have even seen for three mash-tuns! The first step is to study the analysis of the brewing liquor (for we are not all empirical as Mr. Duncan insinuates), and ascertain where the supply comes from. We will say it is a reservoir and watershed; the time to think most of this is in the fall of the year and particularly after a drought. Does that analysis state you ought to bail your brewing liquor? If it doesn’t it should do. It may be that the principals will not make the necessary provisions, and the consultant will not back you up; or, even ignore the point entirely, but practical men are blind to their own interests when they add to boiled mashing and sparging liquor a cold un-boiled supply. Any difficulties are easily overcome by having a separate liquor tank, or where structural conditions interfere, a cold-water coil may be placed in the hot liquor tank, and this should be after the powerful controlling system of a converter. I have seen those reverted to before to-day in an emergency. The usefulness of a converter, whether you are using raw grain or not, I will return to later on.

The value of practical advice in a brewery cannot be denied and, if I may be permitted to say so, I fail to see why we practical mash-tub men should not be more frequently consulted by proprietors of breweries. Why do they pay so much money year after year to specialists, and still go on in the same old way in the summer and back end of the seasons, producing seldom good but often bad and indifferent beers, when any brewer, worthy of so honourable a name, and given a free or freer hand, could work throughout the year with uniform success and satisfaction.

Mash-Tun

I believe that the ordinary mash-tun is susceptible of much improvement and any practical man should, with very little expense, alter it to better the work, even if he be not able to obtain all the objects he may have in view, and one of the principal aims is to have thorough steady command of a wide range of temperatures. I say “steady” because we can take many lessons from the Lager beer brewers. They never attempt or imitate our style of rushing underlets in, in 5 minutes; they go steadily from one heat to another over the space of 20—30 minutes.

Copper

This vessel is a good subject for debate, and the sooner definite conclusions are arrived at the better. The boiling point of worts is 206° F. at the altitude of Johannesburg. The necessity of having dome coppers to obtain the proper cooking point under pressure struck me at once. In the Brewer’ Journal some very pregnant reasons have recently been given why one ought always to boil at 212°. Some brewers like fire, while some prefer steam. Fire must perforce cook better than steam in an open copper, but steam, on the other hand, I will allow, may be used in a dome pressure copper if the fact he kept in mind that pale ale and stout are the two opposites. The former will be quite easily produced with fire under a dome copper with 1½ hours’ boil and regulated pressure, from malt cured on a modern high kiln, without fear of adding too much colour, whilst stout requires as much more fire and pressure, but the chains should be kept moving round in the inside bottom.

Converter

Converters have, independent of their original purpose, developed into three or four more different uses. I have mentioned one, and to my liking it is also a first-rate mash-tun, allowing the brewer to manipulate a wide range for conversion heats, and the non-deposit beer brewer with the nondescript mash-tun will appreciate that. Besides, the ordinary mash-tun comes in for a draining vessel and excise dipping place. The converter can be quickly rinsed out and used for sparge liquor, at any desired temperature, without the aid of un-boiled water, which at the back end of the season you can see, with the naked eye, in some places is full of dirt and filth, stirred up in the watershed and carried into your reservoir by a good shower of rain. I know one of the great drawbacks to converters has been their cost, but quite recently, in fact, a few months ago, a new design and make has been put in the market, and they can now be obtained at half the cost.

Coolers

Coolers are no use at all, all that is required being a receiver to feed the refrigerators.

Refrigerators

A vertical refrigerator gives quite as much aeration as is necessary. In order to economise cooling water (a very great consideration abroad), the worts are run over a vertical refrigerator first, then over a horizontal one, the cold water passing internally the opposite direction.

Mashing

External mixing in the mashing operation can scarcely be excelled by anything but an improved Steels. When the malt supply is some-times slack, sometimes high dried, and the malt made at the Cape is most irregular, no fixed heat can be laid down for working. Given a good malt lightly dried but well cured at 200° or more, the initial heat should be as near 148° as possible for the sole sake of the yeast. The striking heat should be that requisite to combine with two barrels per quarter; with a stand of 5 minutes, after which well-distributed under lets should be commenced, with liquor at anything between 190° and 200°, even if it should require three-quarters of a barrel per quarter to raise the goods to 160°in the mash-tun.

I do believe in thin mashes, and all the colleagues I have worked with will bear me out that thin mashes obtain better extracts (the weight of the first taps will even then be 34—37 lbs. according to the malt). Under-letting should commence at 5 minutes after all the mash is in the tun; this should not occupy less time than 25 minutes.

After under-letting allow the goods to stand 1 hour, and granted a sufficient number of draw-off taps, with a carefully balanced sparge, no more than 2½—3 hours are required to collect the worts in the copper. Why some brewers are so timid about removing the worts from the mash-tun (after it has been duly converted) I cannot comprehend. If they think by prolonging the process with good material they will obtain more extract, all I have to say is they are sadly mistaken.

The sparging heat should be under 170° throughout, and allowed to drop gradually towards the end. The advantage the home export brewer has over us out there is he has plenty of yeast at command, and he can indulge in a very much higher initial heat with impunity.

Boiling

I was going to say more about boiling, but this point has been treated recently in the columns of the Brewers’ Journal, and I cannot do better than recommend you to read it, keeping particularly in view the advantages of pressure boiling.

Fermentation

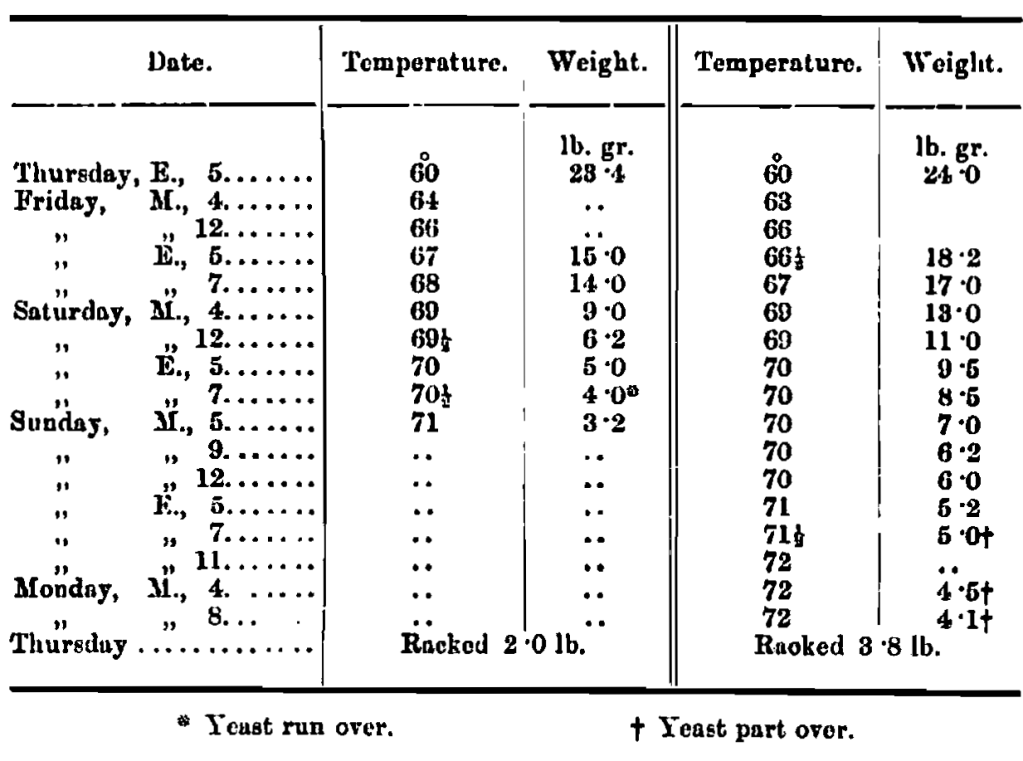

To obtain a regular and desirable fermentation gives trouble and concern all over the country, even when there is a copious supply of chilled or well water. The following is a copy of two fermentations side by side for comparison, the first, when the imported yeast was cultivated up to a brewery supply vigorous and useful; the second, when the same crop will be discarded from use in best beers :—

This latter fermentation is a nice thing to confront you. It had all the coaxing possible to come down. I lightened the top yeast three times before finally giving it up and running it over. It turned out all right, but you must get them down for bottling and avoid fret even in the cask.

A peculiar thing about the climate is, if your beers fret they never recover again like they do in this country—they go sour at once. It makes you look round the comers for help to get slow fermentations down; and I discovered that a small percentage of raw cane sugar did it. You have all read what Mons. Petit has lately found out and published. I think after he has had as long an experience with it as I have had, he will find his yeast very much weakened, and become quickly sloppy. Cut his percentage in half, and still he will retain a very valuable asset, with all the advantages he enumerates in a warm climate, coupled with a fairly good spin of keeping your yeast crop, Mons. Petit is said to have approved of the use of cane sugar without previous inversion, but I am sure if he brews with a fair proportion of sugar the most of it had better be inverted before it goes into the copper.

The “ticky” beer you have heard of is, when it can be got, mostly brewed from Colonial barley malt with a good percentage of sugar, at low initial heats. Immediately before bottling it is racked bright from leaguers into hogsheads or half hogsheads with Kraüsening and raw cane sugar priming, regulated in quantity by the season of the year or the distance it has to go. Kraüsen from the previous day’s brew always preferred. The raw cane-sugar solutions precipitates the sediment and dispels the yeasty haze in a day or two; at the same time the condition will be up and the beer mostly consumed within a week.

An exceedingly large proportion of all beers brewed were bottled. I am not certain of the exact proportion, but it would not be exceeding the mark if I say five-sixths all over, except at such an exceptional time when so many troops wore in the country during the Boer war. It is noteworthy, however, how strongly everyone adheres to the custom of drinking bottled beer, and a brewer going out there should be specially well up in it to make his mark.

In a country where underground cellars are really mostly required, it is surprising to find largo hotels and bars without one, quite conspicuous by their absence, and drawing racked beer from behind the counter.

Beware of the injudicious use of preservatives; they develop so prominently in the bottle. Lean upon good sound material, sound heats in your work scrupulous cleanliness, and a spring cleaning within your walls and roof every year. Care has also to be taken that all stable manure, refuse yeast, spent hops, unsold grains, etc., are carted clear of the premises every day to prevent contamination—a rule that many brewers at homo would do well to imitate.

There are several well-equipped and up-to-date Lager breweries in the different colonies, conducted under ice-plant installations, and a credit to any country. There are also a number of small concerns which seem to flourish under what I call exceptional difficulties without ice plants. It is a credit to them to turn out such an article as they do against their powerful neighbours. It reminded me of our home style of finishing in the carriage cask and topping up on the stillages.

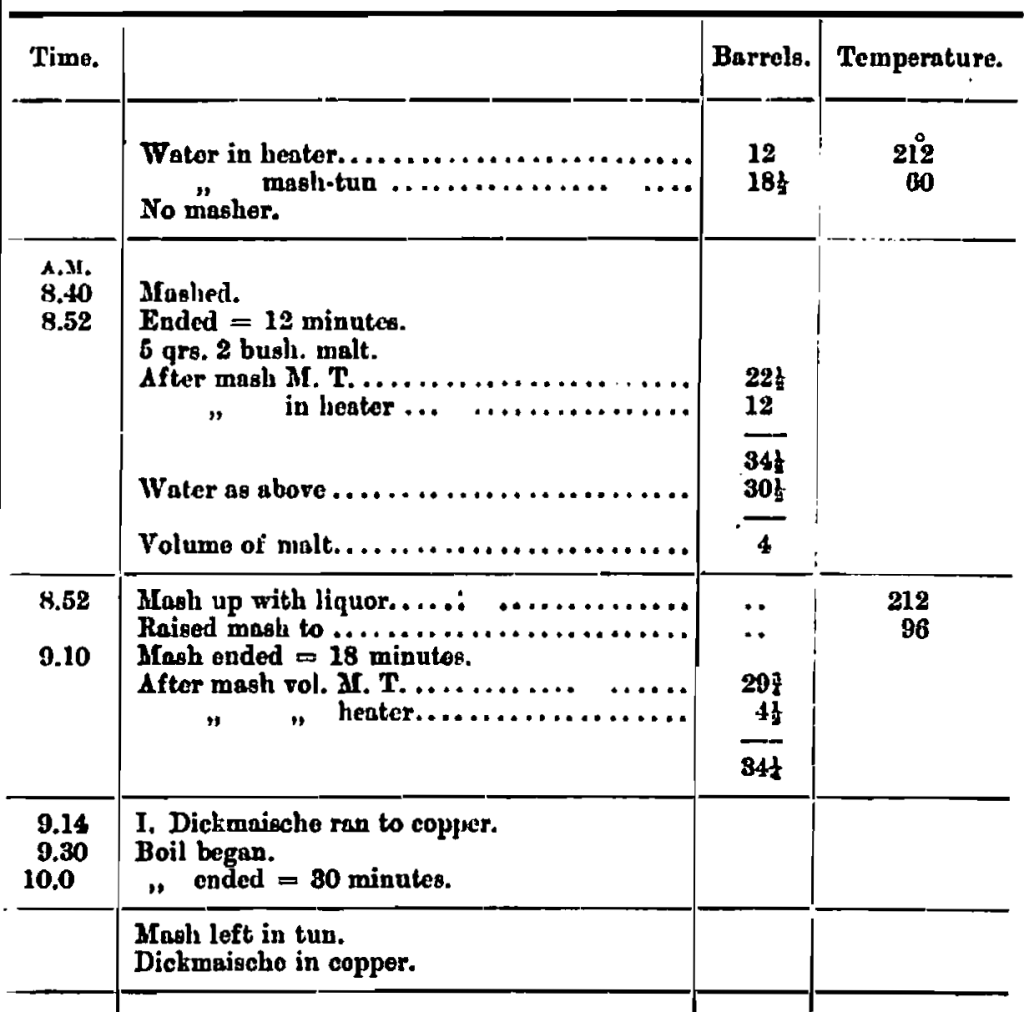

I have transposed a brewing from hectolitres, kilogrammes and Reaumer to our mode of expression:—

The hops used were of the choicest Halledau (sic). The yeast used during fermentation in an open vat was originally bottom yeast, and still retains the Lager flavour, but it is now to all appearance a top-fermentation. When the fermentation was far enough down, kept as cool as circumstances would permit with ice in a cylinder suspended in the centre of the fermenting vessel, it was run down into casks and finished by continually topping up on the stillages.

The beer was then pumped over into large oval ended casks or vessels; when sufficiently stored, forced by carbonic acid gas pressure through niters into pitched carriage casks, and drawn in the saloons or bars by the hand pump in u foaming and fairly brilliant condition.

I may say, heavier gravities are also made up to 14 per cent. Balling or about 58° specific gravity, also bottled and sterilized, and I could scarcely believe at first that in such a warm climate such work could he accomplished with a very limited supply of well water.

On the other hand, when in Pretoria it was most tantalizing to me to see clear crystal water, on u hot summer’s day, running to waste along the open street channel, when most of the country lay panting for want of it.

Discussion

Mr. A. D. CURRIE referred to the heavy rains in South Africa, and said that he thought that frequent analyses of the brewing liquor would be necessary, as the water, being surface water, would necessarily alter in character. He would like to know what was Mr. Laurie’s specific objection to the mash-tun. A mash-tun was not a converter, but essentially a filter; of course, if n converter was required, it was a different thing, but it was difficult though not impossible to do a converter’s work in the mash-tun, and if they required a converter that was no reason why they should discard the mash-tun. He did not approve of under-letting immediately after mashing, nor did he see any reason why it should occupy as much as ¾ hour. He did not see the necessity of pressure boiling under the circumstances named by Mr. Laurie. Would Mr. Laurie explain what he meant by “fret”? He presumed Mr. Laurie would not bottle his beers until they were in condition. He would also like to have some details of the ice plant, as he was very much interested in this question just now. He would also like to know whether Mr. Laurie preferred the ammonia method or the carbonic acid method.

Mr. LAURIE, in reply, said he agreed with Mr. Currie’s remarks upon the necessity of taking very frequent analyses under such conditions as prevailed in South Africa. With regard to the mash-tun his only complaint was that so many of them were of such primitive construction. With regard to under-letting, he applied his underlet 5 minutes after mashing, for the sole purpose of producing a more gradual rise of heat in the mash-tun. With regard to “fret,” he said he dare not postpone bottling until the beers were in condition, as they would be certain to fret, and South African beers never recovered from fret as the beers of this country—they invariably went sour. With regard to ice plant, and the ammonia and carbonic acid methods, he preferred the latter.

Mr. O’CONNOR said he had had experience in Colonial brewing, but not with such extreme temperatures as Mr. Laurie had mentioned; he had brewed in India at 7,000 feet above sea-level, and the boiling temperatures were, therefore, lower than those recorded by Mr. Laurie. He remembered one instance in which, working without ice plant—and river water at 70°, pitching took place at 75o, and fermentation rose to nearly 100°. It was, perhaps, lucky that on that occasion consumption of the beer took place within a few days of the brewing. He presumed that by Colonial malt the author meant malt made on the spot from Colonial barleys. He (the speaker) had tried malting in India from local-grown barleys, but found it almost impossible to produce malt that was not covered with mould, in consequence of the damage caused during the threshing, which was carried out by oxen. It was very unusual to find more than about seventy whole corns in a hundred, and it would be interesting to know how threshing was carried out in Africa. With regard to the exportation of hops, he had found that the most satisfactory method in India was to have them compressed to about half their bulk in iron cylinders, in which carbonic acid was injected and the lids screwed down upon an india-rubber flange to maintain an air-tight condition. He also inquired whether Mr. Laurie washed his yeast, a precaution he had found absolutely necessary in India, whore in conjunction with washing he had used a small proportion of salicylic acid in the water. By mixing the yeast with this, and skimming off a little portion from the top and leaving the actual sediment, ho found—if the right proportion were used—this acting as a tonic actually strengthened the yeast. He believed Mr. Laurie said his natural temperature in the copper was 206o, and that he boiled at a pressure of 1½ lbs., previous to which he believed he had stated that it was necessary to raise to 212°, and a pressure of 1½ lbs. was hardly sufficient to raise the temperature from 206° to anything like 212°, the normal temperature at sea-level. He would also like to ask why Mr. Laurie started with an initial mash temperature of 148°, which struck him as low, unless there was an unusual restriction of the diastase in the malt. It appeared to him that Mr. Laurie was using a very low initial temperature, and he would like to ask whether he considered that a desideratum and one due to any local circumstances. Then, on the subject of under-letting, Mr. Laurie had said that he would commence within 5 minutes of mashing. He (the speaker) could not understand why such under-letting should be advantageous, and if a higher temperature were required, why it was not obtained with such an initial temperature as would give it? He would like the members present to give their opinions on the 5 minutes underlet, and on the general advantage of using underlets for any purpose other than lightening goods on the place, but the members present were unable to say that they had put Mr. Laurie’s method of immediate underlet into actual trial. He would like to ask whether Mr. Laurie used Lager casks in producing his beers. The most satisfactory process he had come across was to have Lager casks containing about ten or twelve barrels, and put the fresh racked beers into these, and when they were in condition, to force the beer by carbonic-acid pressure into trade casks.

Mr. LAURIE, in reply, said he had never had any occasion to use a high temperature for fermentation. Only when run out of well water, and the ice plant broke down, had he ever been obliged to pitch at a high temperature, and even then he had found the beers to keep fairly well. The Colonial malt to which he had referred was made from Colonial barley, and they must be more advanced in South African Colonies—though he had thought them very much behind—than in India, because, though they used at one time to thresh by mules tramping on it, they had now modern threshing machinery, which went from place to place. He admitted the usefulness of washing the yeast, and he had found salicylic acid quite satisfactory if the proper quantity was used. He washed his yeast, but took care to select only the best. By running the top water off, he got rid of the salicylic acid, as pointed out in his paper. He found that it also drew away any sarcina contamination. He mashed for an initial of 148° mainly for the sake of his yeast, as it crippled the yeast-producing power of the wort if the temperature was over 150°. At home here they had a yeast supply to fall back upon, but there they had none. If he had his own way, and no yeast to consider, he would have made his initial heat 152—154o . With regard to starting the underlet in 5 minutes, he maintained that if they extended for 25 minutes, the half of their goods at least would be standing at what they would consider a normal time to stand for the first heat. He had never used Lager casks for ordinary English beer, but only for Lager-brewed beer. In the south, where the bars were deficient in cellar room, when they got beer out for sale it was racked in the same way as was done here; but in the north they had all the approved principles of German filters and carbonators, and the racked beer was put through the filters charged with carbonic acid gas.

The CHAIRMAN asked if Mr. Laurie would adopt the same method in this country.

Mr. LAURIE replied that as he had found the method answer so well in South Africa, he had adopted it since in this country, and with excellent results.

Mr. O’CONNOR asked, if with regard to this food for yeast the author meant any special type of albuminoid, or sugar upon which the yeast could act more easily.

Mr. LAURIE replied that he referred to the ordinary yeast foods, so many of which were obtainable now-n-days, and he repeated that the yeast could be kept far longer with the lower than with the higher initial.

Mr. LINLEY said he did not agree with Mr. Laurie in condemning rakes, and wished to know whether he had rightly understood Mr. Laurie.

In reply, Mr. LAURIE stated that he adhered to his original statement, that so far as his experience went he found rakes quite unnecessary.

The CHAIRMAN said that the subject seemed to him a particularly suitable one for discussion. If he were asked to put his finger on the particular feature which distinguished the brewing and malting trade from all others, it would be the wonderful divergence of opinion and practice on the part of practical men. They had already had a few finely illustrative examples that evening, and he was sure if the discussion continued a little longer they would get many others.

Mr. J. W. POTTER asked where Mr. Laurie got his changes of yeast from, England or the Continent, and Mr. Laurie in reply said that the yeast for British beers was obtained from England and that for Lager beers from the Continent.

Mr. H. W. WATSON did not agree with Mr. O’Connor in applying a very high heat at the initial stage, because he understood from text-books that the diastase would be much more seriously crippled by such a procedure than it would be with the same temperature in the presence of a certain amount of maltose and dextrin.

The CHAIRMAN said he had much pleasure in proposing a cordial vote of thanks to Mr. Laurie. He congratulated him from several points of view, and particularly because he had done his best to break down a barrier which had unfortunately arisen in connection with their Institute, probably in common with other Institutes, namely, the belief that members themselves need not trouble to read papers. Quite recently Mr. Currie, by reading a paper on “Practical Malting,” had started the ball rolling, and Mr. Laurie was now seconding the effort. He hoped that many other members would come forward and render similar service.

Mr. O’CONNOR seconded the vote of thanks to Mr. Laurie for his interesting paper. It was especially interesting to him, as he had been through the same mill himself. He incidentally observed that Colonial brewing proved a splendid education, as, in the absence of experienced workmen, it showed a brewer the extent of his own ignorance in minor details—more especially where his only assistants were illiterate natives.

Mr. LAURIE suitably acknowledged the vote of thanks.