MEETING of the SCOTCH SECTION, HELD at the CALEDONIAN 8TATION HOTEL, EDINBURGH, on TUESDAY, December 19th, 1922.

Mr. A. S. Stenhouse in the Chair.

The following paper won read and discussed: —

Some Notes on Flaked Maize.

By A. E. Berry, B.Sc.

Careful attention is always paid to the source und conditions of growth of malting barley, but the name cannot be said of the selection of maize which is eventually made into grits and flaked for brewing purposes.

Maize comes to this country from various places, and from time to time climatic and other conditions affect the crop in a manner that undoubtedly detract from its ultimate brewing value, and because of the great necessity for stability and soundness it is essential that only carefully selected maize should be employed for flaking.

Since the war one of the largest suppliers—Roumania and the Danubian country—have been unable to export, though it is expected that this may be remedied in the near future. Roumania has in the past exported as much as 1,000,000 tons in a season, and it is anticipated that in course of a year or two she will be able to resume shipments on a liberal scale, in which case it may be reasonably expected that the market will reach more favourable figures than have prevailed for some time past. Until, however, there is a definite indication of shipments being resumed, and until the Export Tax is decided, it is impossible to anticipate what attitude Roumanian growers will adopt.

At the present time the Argentine, United States of America and South Africa are supplying the bulk of our maize, though shipments have recently been received from Brazil; the condition of the maize, on arrival from the latter country, however, leaves much to be desired and the greatest care would be necessary if satisfactory flakes arc to be manufactured from it.

South Africa and Rhodesia last year exported approximately 300,000 and 50,000 tons respectively, but Plate maize is the most sought-after variety and supplies the bulk of the requirements of this country for brewing purposes.

The Argentine maize possesses many advantages, and it may be placed first from a general utility standpoint, after that—South African and Danubian maize. The “mixed maize” from America finds its place at the bottom of the list of shipments because of its varying character and because at certain times of the year it is so liable to changes, in consequence of the corn being harvested and shipped under difficult conditions.

African maize during the punt year has been arriving in a satisfactory condition and is being more extensively used both in this country and on the Continent. Unfortunately, the crop this season will be a small one owing to the drought, and it is not expected that much will be shipped before a new crop becomes available early in the second half of the next year.

For some months past Argentine maize has not been easy to obtain owing to shipping difficulties and the abnormal dampness of the season. In many cases shipments were arriving out of condition, but it is expected that recent arrivals and shipments now afloat will be better, although the greatest care is necessary at such periods in the treatment of the maize before it is finally packed in the form of flakes for use in the mash-tun.

Maize as it arrives in this country varies little in composition from the different countries of origin, although physically there is a very considerable difference both in appearance and in suitability of working for the different purposes for which it is used. For the flake maize manufacturer this physical property becomes more accentuated in mixed American and certain grades of African maize, because although the ultimate flaked maize may be of a high standard from the point of view of chemical analysis and brewing value, yet the flakes are more liable to fracture and crumble when packed into bags, and in consequence have not the same surface when entering the mush-tun, and lose value from the point of view of probable extract and drainage.

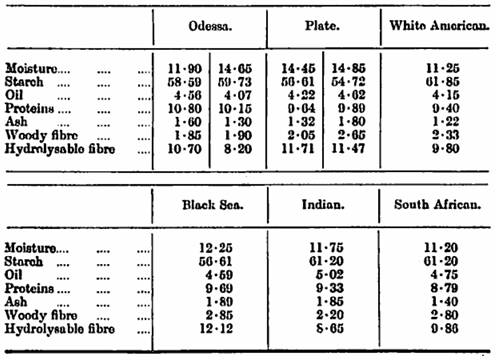

So far as these latter features are concerned, Argentine Plate maize of the right quality is the most suitable for the manufacture of brewing flakes. The following are some typical analyses of maize imported from different countries in which it is grown and will illustrate the composition on arrival in this country.

These figures show that the variation from a chemical standpoint is very small indeed, but the brewer considers a physical and practical test of his malt equal to, if not more important than the analytical data of the chemist—so the flake manufacturer has to consider his raw material.

Attempts have been made from time to time to flake maize in the country of origin, and to send to this country ready for use for the brewing and other industries. Experience has shown, however, that excessive moisture is taken up during transit, and accordingly the flaking of maize abroad for use in brewing presents disadvantages that undoubtedly outweigh any economy or benefit that foreign manufacture may present from the buyers’ point of view.

The United States Department of Agriculture conducted some experiments in the early part of the year in connection with the effect of bad or lengthy storage of maize, and the result from absorption of an excessive amount of moisture which imported maize must be subject to from time to time. Messrs. E. Thom and E. Le Fevre proved conclusively that not only do various moulds, but also bacteria— many of an objectionable character—develop when the percentage of moisture ranges between 13—15, and finally conclude their investigations with the statement that flakes ought to be kept around 8 per cent, moisture, a figure with which I am entirely in accord. In my opinion the most desirable moisture figure for brewing purposes is between 8—10 per cent. When flakes are too dry—that is when the moisture content has been reduced to 4—5 per cent, the flakes undoubtedly lose their flexibility, and become more liable to break, consequently they do not offer the same drainage facilities in the mash tun. In addition, the surface and general porosity of the fluke is not so favourable to the action of the diastase in the tun.

A recent sample of imported Belgian flakes was found to contain 12·4 per cent, moisture when delivered to the brewery, and a further sample of this material contained 11·55 per cent. This figure is too high and is on the border-line where the development of objectionable characteristics and flavour are very likely to occur, as demonstrated by the investigations just referred to.

Owing to the variability of “mixed maize” it is impossible to produce a flake of uniformity as regards not only appearance but also solubility and stability. This objection would not arise if the maize could be first sorted and the different corns treated separately, but no mills are adapted to such methods of treatment, and, in consequence, imported flakes, generally made from corn of the character referred to, may possess varying characteristics which are non-existent in the flakes made from uniform Argentine Plate or South African maize. If the flakes from this imported maize be carefully separated by hand the analytical results obtained show that there is a difference of composition in the flakes made from mixed American corn.

In consequence of the comparatively “soft” nature of some maize the percentage of flakes obtained from this type is very much lower than that produced from one of harder or more vitrified character. Again, in some make the starch exists in a condition which renders it difficult to satisfactorily gelatinise or rupture the starch cells in such a manner that the diastase of the malt in the tun can exercise its maximum effect, and it is necessary, therefore, when manufacturing flakes from this maize to take special precautions to guard against that difficulty.

The process of “flaking” is one that depends entirely upon mechanical methods which have now been brought to a high state of perfection. Not only must the husk and fibrous matter be removed, but the original oil content —reduced to below 1 per cent.— and all foreign or extraneous matter eliminated. Manufacturers in this country employ various types of machinery and processes for the accomplishment of the above object, but they all more or less attain the same desired end—as is evidenced by the general uniformity of character in flakes now produced for the brewing industry. The following are a few typical analyses of flaked maize as made by different British manufacturers: —

Generally speaking, the process of manufacture may be described in the following manner:

(1) The maize as imported is first carefully screened and winnowed to remove the lighter hu6k and parts of the maize ” cobs ” which, if present, would detract from the quality of the finished flakes. It is important, however, to arrange that sufficient of the cell-fibre shall remain as to leave a heavy and insoluble husk, so that when the whole of the starch has been removed by the action of diastase there is a medium that will have an important bearing on mash-tun drainage.

(2) The maize is then passed over powerful electric magnets to remove iron in the form of nails or other small pieces of metal which arc pre sent from time to time, and if not removed would do irreparable damage to the different machines through which it must pass in process of manufacture.

(3) The maize in the whole state is then passed through a series of steel rolls termed “break rolls,” which are set at varying positions so as to break the corn to regulated sizes suitable for subsequent treatment.

(4) The broken maize is passed through what are called “purifiers,” and these machines are so designed that they very effectively separate the grits or starchy portions of the maize from the germs or oily and fibrous portions which later are transferred to the department for the manufacture of cattle foods. These purifiers work on the principle of the difference in specific gravity between grits that are required for flaking and germs that are later taken into the manufacture of cattle foods. The difference between the specific gravity is so slight that great care is necessary in the working and adjustment of these purifiers and it is at this stage of the manufacture that a mistake would result in the presence of too high a percentage of oil in the ultimate flakes.

The germ of the grain is most readily attacked by bacteria and other organisms, and, in addition, objectionable flavours are likely to arise when it is not sufficiently eliminated. The degermed portion has been proved by experiments to be less readily attacked than whole maize meal, and in consequence the purified grit which is eventually flaked constitutes a very sound and reliable brewing material.

It is customary to employ a cyclone of air for the removal of the lighter portion which is termed the “germ,” and whatever method may be adopted the separation of the germ from the grits must be carried out as efficiently as possible. As a matter of fact, it is desirable to repeat this process of separation several times with certain qualities of maize.

After the grits have been separated in the manner described they ought to be practically free from germ, and contain less than 1 per cent, oil, and will naturally contain a much higher percentage of starch than was present in the original maize. They are then presumed to be in the most purified form for the manufacture of the final flakes and are occasionally used in the brewing industry as separated at this juncture under the name of “brewing grits.” However, the starch present in these grits would be altogether unsuitable for addition direct to the mash-tun in consequence of the fact that the surface they present to the diastase of the malt is so small and of such a character that very little ultimate extract would result.

These maize grits arc therefore subjected to treatment which ruptures each individual starch cell and produces a soluble gelatinised condition which is then in a form that can be completely converted by the diastase from the malt into soluble extract. This process consists in conveying the separated grits through gelutinisers which arc made in various forms, but which, without exception, embody the same principle. This consists in subjecting the grits to treatment in an atmosphere of steam and for a period sufficient to entirely rupture every starch cell and complete the gclatinisation of the same. This gelatinisation is of great importance to the brewer because it determines the ultimate extract that will be obtained from the flakes, and in addition it has a most important bearing upon the composition of the ultimate extract yielded by the flakes in the mash-tun.

The process of cooking “grits” converts part of the starch into maltose and dextrin and part into perfectly soluble starch.

To ascertain what effect different lengths of treatment and temperatures have upon the dextrin figure in flakes a number of specific rotatory powers were determined and the readings calculated to dextrin. It was found that the dextrin figure could be carried from 7·22 to as high as 15·22 per cent. Flakes wore then submitted to a double treatment of cooking, and the dextrin content was raised from 9·69 to 11·31 per cent. There is no question that length of treatment and degree of temperature have the most; important bearing upon the ultimate com position of the extract of the flakes which the brewer ultimately obtains in brewing, and at the same time the actual amount of extract.

To investigate the amount of extract purified maize grits were subjected to varying steam temperatures through the same machine, and for equal periods of 45 minutes’ duration with the following results: —

The extract in each case was determined by mixing with identical quantities of the same malt wort, and it will be noted how temperature increases soluble extract. At this stage of the manufacturing process the surface presented to the diastase is of such a restricted character that the actual conversion into brewers’ extract is small, and it is necessary to complete solubility by means of flaking when the whole of the starch becomes available for extract. Further experiments were conducted with temperatures exceeding 235° F. without any improvement in results, and consequently the temperatures quoted constitute those that aro best adapted for efficient manufacture, although it will be seen how a slight variation in that respect will affect the value of the ultimate product.

After the gelatinised grits pass from the cooking process described they are ready for the final treatment of flaking, which possesses no particular features. The method of flaking is common to all manufacturers and consists of passing the gelatinised grits between steel rolls which are screwed together and can be adjusted so as to produce flakes of varying thickness. It will be found in practice that flakes vary in thinness from time to time and this depends upon the manner in which the rolls are adjusted by screwing, and it is important that the flaking should be of a character which will ensure the greatest possible surface to the goods in the mash-tun in order to give full extract.

In order to show the importance of the degree of surface presented by flakes from the standpoint of yield of extract, a series of experiments was made using flakes of varying degrees of thinness. In each case the grits used were of identical composition, but they were passed through rolls for final flaking that were differently adjusted.

Although the extracts from the thicker flakes were low in consequence of the restricted action they presented to the diastase in the malt wort, yet the loss of extract was entirely due to the thickness of the flakes and not to the actual condition of the starch present. This was further shown by mashing some extra thick flakes that only gave an extract of 77 lb. when mashed for one hour, to a further treatment with malt wort for an additional two hours, when the extract rose to 83 lb. The inference to be drawn from these experiments is that although the earlier process in the manufacture of flaked maize may be satisfactorily performed, yet, for a brewer to obtain the full advantage of the extract available, the flakes must be manufactured in a well-judged fine condition so as to present the maximum of surface for diastatic attack.

The question of ultimate extract in the mash-tun when using flakes will depend upon the diastatic capacity of the malt used. The experiments recorded in this paper have all been carried out with a malt of a diastatic capacity of 25° Lintner, and mashing at the rate of 25 per cent, of flakes and for a period of one hour. If malt of higher diastatic power is used the conversion of starch is more rapid as the following results show: — When working on the same percentage as above described and using a fairly thick sample of maize flakes—an extract of only 88·7 lb. was obtained. Repeating the experiment and using a malt of D.P. 105°, the extract over the same period of half-an-hour was 96·6 lb.—being an increase of 7-9 lb. When mashed for one hour with a malt of D.P. 25° the extract was 94·4 lb… but with a malt of D.P. 145°, the extract became 101·4 lb. The inference is conclusive as it is to be anticipated the higher the diastatic capacity of a malt the quicker is the saccharin cation of the flakes. With the ordinary malts in use there is sufficient diastase for rapidly and efficiently converting any proportion of flakes that arc likely to be employed. The extract yielded will depend upon the manner in which the flakes are mixed with the malt grist; also upon the porosity and buoyancy of the mash and upon the evenness of the sparge.

After leaving the flaking mills the flakes arc conveyed by mechanical means to dryers in order to remove the excess of moisture that it was necessary to impart to the grits before they were submitted to the cooking or gelatinising process already described. These dryers are constructed by the different manufacturers according to their own particular methods, and must be so arranged that there is a minimum of breaking or disturbance of the actual flake. It is important also, where air drying is favoured, to use purified air, so that the final flakes when packed into bags may be as sterile as it is possible to make them. It is also necessary that the bags in which maize is packed should be of a substantial nature and of a fine close texture which will not only act as an air filtering medium, but will also prevent any undue absorption of moisture. It is very largely on this account that imported flakes are invariably found to contain high moistures. The return of empty bags is troublesome and consequently exporters to this country are forced to economise by using a bag less substantial in character than is usually employed here, with the result that absorption of moisture during transit frequently assumes serious proportions.

When the process of flake manufacture is conducted with due care the use of flaked maize by the Brewing Industry presents advantages— not only from a financial point of view, but also on account of the increased stability and general character of the wort before fermentation. The extract from a well-made flaked maize will be found to be of a uniform composition, and in consequence it constitutes a very valuable adjunct for stabilising brewing wort; it also presents a means of correcting or reducing an excessive percentage of nitrogenous matter in malt, and it is also of importance in connection with the reduction of colour. Every brewer appreciates the advantage of lining—under certain conditions—high dried malts, which produce a little more colour than is necessary, and on such occasions the employment of flaked maize has undoubted advantages. Generally, it will be agreed that flaked maize has played—and will continue to play—a most important and valuable role in the Brewing Industry.

Discussion.

An interesting discussion followed in which Messrs. Wilson, Hendry, Kennedy and Hopkins took part.