MEETING HELD ON, 9th DECEMBER, 1897, AT THE GRAND HOTEL, BIRMINGHAM.

Mr. W. W. Butler (Vice-President), in the Chair.

The following paper was read by Mr. Cecil Revis, in the absence of the author (Mr. R. F, Wood-Smith) :—

The Bacteriology of Yeast. (Part I.)

By R. F. Wood-Smith, F.C.S.

In this paper I desire to place on record the results I have obtained from some experiments, which were carried out with the object of ascertaining what bacteria normally occur in English high yeast, as the latter is employed in the production of beer, and I may add that these experiments are to be regarded as preliminary to other work which I am carrying out on the subject, the object of which is to ascertain how far these normal bacteria may, under certain conditions favourable to themselves, become parasitic to the yeast. This being the ultimate aim and object of my researches in this domain, it will appear obvious to all that in any work of this kind it is necessary to first study the normal conditions; and it is these normal conditions which are described in this paper.

In dealing with the subject, I have ignored the various types of wild yeasts mot with, it being my intention to limit the work solely to the bacteria themselves, including under this term the varioustypes of bacilli, micrococci, sarcinæ, and spirilla, should these occur.

I will first deal with the methods of separation.

When we consider that in any brewing yeast of normal purity the number of bacteria present is very small compared with the saccharomycelial cells, it is evident that, apart altogether from theinhibiting action of the latter, some difficulty must be experienced in separating the occurrent forms; and for this purpose the following details have been found to be necessary.

The yeast to be examined is collected from the squares with a sterilised platinum needle, and this is added to a few c.c. of sterile distilled water. This suspension is thoroughly shaken, and is thenready for the investigation. It was found that in good yeasts so few bacterial cells were usually present as to render it impossible to dilute down the suspension; which would have been extremely desirable if possible, since we should then have been able to have reduced the total cells (saccharomycelial and bacterial) to a few hundred per c.c., and thus have avoided subsequent overcrowding. But since this was found to be impossible on account of the reason stated, cultivation bad to be carried out in a very dense state under conditions which were favourable to the bacteria and unfavourable to the saccharomycetes; these preliminary and overcrowded cultivations were prepared in a manner subsequently described, and the bacterial growths, though at first largely contaminated with the yeast forms, could be subsequently purified by successive sub-cultivations.

In carrying out the separation the cultivation medium employed for the primary step was that known as peptone broth agar-agar, commonly called simply agar-agar for brevity, the nutrient material of which is peptonised beef broth, which is rendered solid by the addition of from 1½ to 2 per cent, of Japanese isinglass.

This medium is able to afford relatively greater nutrition to bacteria as a whole than yeasts, as will be seen from the following facts:—

Firstly. The percentage of carbohydrates in the agar-agar is very small indeed and it is a well-known fact that yeasts can grow far more strongly and actively when nourished by a medium containing compounds such as glucose, maltose, &c., than they can when nourished by media in which carbohydrates are absent.

Secondly. The percentage of albuminoids in the agar-agar is very high when we compare it with those media, such as wort, &c., which are favourable to the growth of yeasts, and this high percentage of nitrogenous matter is conducive to the active growth of most bacteria.

Thirdly. The agar-agar is a medium which renders possible incubation at a comparatively high temperature without liquefaction taking place. Comparatively high temperatures are favourable to most bacteria and unfavourable to the saccharomycetes.

The temperature at which incubation was carried out was about 37° C. (98° F.).

It may here be remarked that it was for the purpose of this high temperature incubation that nutrient agar-agar was used in preference to the ordinary gelatin, since the latter melts at a temperature of about 25° C, when no separations can be made.

The separations were effected thus:—

Petri dishes were tilled with the sterilised nutrient agar-agar which had been melted at a temperature of 80° C, to the extent of about 8 c.c. per dish, and the medium was allowed to set at the ordinary temperature of the air.

From 0·25 to 0·5 c.c. of the yeast suspension was transferred with the ordinary precautions against foreign contamination into the solidified agar-agar in the Petri dishes, and this was thoroughly distributed over the surface of the medium with a sterilised platinum .spatula or glass wool brush.

The prepared dishes, or “plates,” as they are commonly termed, were then placed in the incubator at 87° C, and allowed to develop for from 18 to 24 hours.

On examination at the end of this period of incubation the whole of the agar-agar surface was found to be covered with a very great number of minute colonies, and those were found on examination to consist of Saccharomyces cerevisiæ and other types of saccharomycetes, but with these there were always present various numbers of bacterial colonies, and these in nearly all cases wore found to have grown very much more strongly than the yeast. The bacterial colonies, although largely contaminated by the surrounding saccharomycetes, were then carefully picked off with a platinum needle, and in as pare a condition as possible transferred to sterilized nutrient broth tubes.

The broth tubes were thoroughly shaken, and from platinum needle loopfuls of the inoculated bouillon, sub-plates of both nutrient gelatin and agar-agar were prepared. The incubation of these secondary plates was carried out at temperatures of 20° and 37° C. respectively, when after periods of 48 hours at the lower and 20 hours at the higher temperature, examination showed the bacterial colonies to have developed in varying states of purity, with small members of saccharomycelial colonies, which did not, however, prevent the preparation of pure cultures of the bacteria present. It is as well here to point out that in preparing the secondary plates, different dilutions—in accordance with the practice in vogue—were employed, in order that the best state of separate colonies might be obtained. Having then separated the various bacteria present in an individually pure condition, these were cultivated on the various media usually employed for the purpose and identified in the ordinary manner.

As I have already stated, I do not intend in this paper to discuss the subject of “Antagonism between Bacteria and Yeasts,” but the fact that yeasts are under certain conditions capable of absorbing and destroying by their own metabolic action various types of bacteria must be stated, in order to explain the very varying quantitative results obtained in the experiments. The relative number of bacteria to yeasts varied in fact to such a large extent that the figures obtained must be regarded as wholly valueless, and the qualitative results only are therefore given. It may, however, be here stated that roughly speaking the average proportion of active living bacteria to saccharomycetes found in the yeast was I : 10,000, although on microscopical examination a far larger proportion is usually formed, but including dead or partially destroyed forms. The actual experimental results obtained will now be given, the bacteria mentioned having been separated in the manner described.

In all the experiments made the yeast examined was taken from 3 to 4 inches below the surface of the rising mass in the squares, as it was thought that by carrying out the investigation in this manner at different times after pitching, the best comparative results would be obtained.

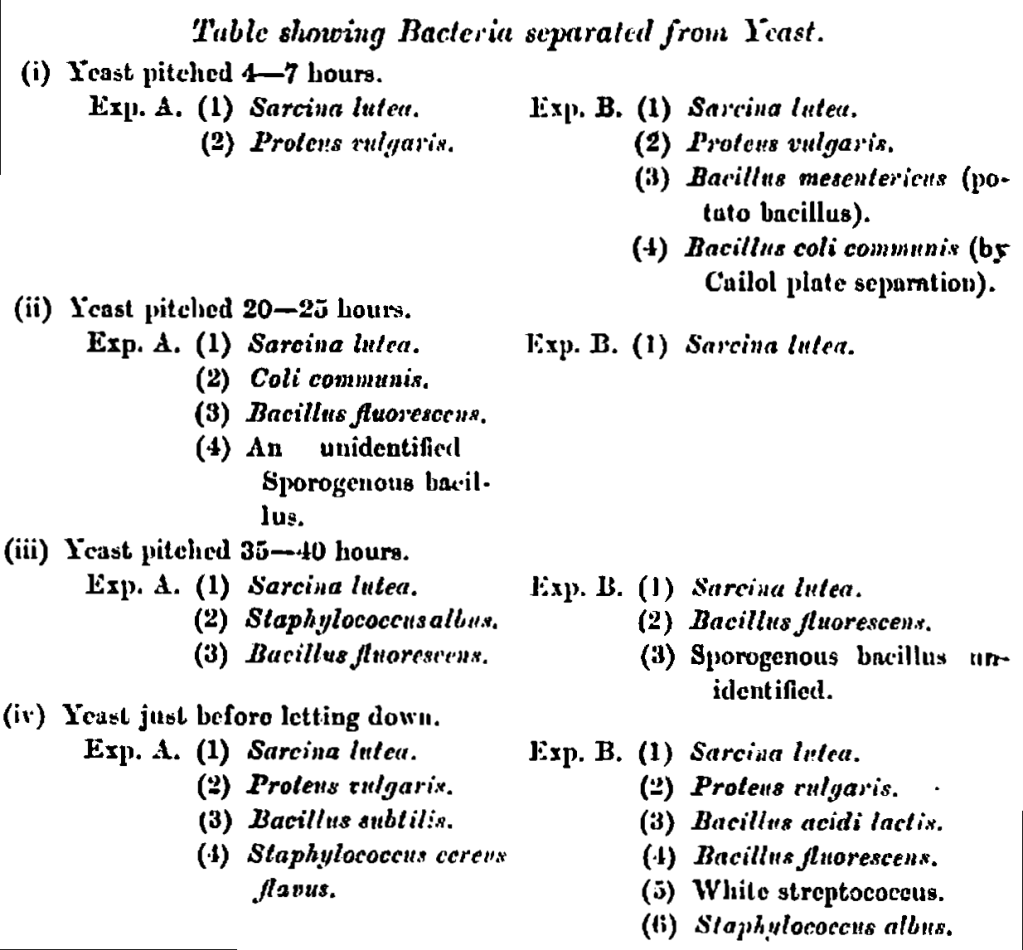

Altogether eight experiments were performed, two with yeast which had been pitched from four to seven hours, two from yeast 20 to 25 hours old, two from yeast 35 to 45 hours old, and two from yeast on the surface just before letting down. In all cases suspensions were prepared in the manner described, and the micro-organisms separated by successive plato cultivation. Gelatin plates to which 0·25 per cent, of phenol had been added were also inoculated from the intermediate broth suspensions already described, in order to ascertain whether the Bacillus coli commnuis was or was not present; by this method the bacillus of typhoid fever could also have been separated, bat it was not expected that this micro-organism would occur, and the experiments made fulfilled this expectation.

The- following table gives the various types of bacteria separated from the different yeast suspensions prepared.

In reviewing the foregoing table we see that the Sarcina luten occurred the most often, it was in fact found in all the yeast suspensions examined, whereas the other micro-organisms separated occurred in the following number of experiments:—Proteus vulgaris, four times; Bacillus fluorescens, four times; Bacillus coli communis, twice; Staphylococcus albus, twice; and the following micro-organisms once each, Staphylococcus cereus flacus; Bacillus subtilis; Bacillus mesenterieus; Bacillus acidi lactis; white streptococcus, and the unidentified sporogenous bacilli.

In considering the results obtained by the experiments we may, I think, draw the following conclusions :—

In the first place, the bacteria separated are all common inhabitants of air, water, refuse, &c., with the exception of the two unidentified sporogenous types, and there is reason to regard these as distinctly not of this class.

The fact that common saprophytes were found to occur was what must have been expected, when we consider that it is possible in the open squares as used in the English breweries for these forms to be constantly falling upon the yeast.

The fact that these bacteria are very rarely able to develop under these conditions is accounted for partly by their preference for an oxygen-containing atmosphere, and partly by the overcrowding and germicidal action of the yeast cells themselves; as well as by the fact that the worts in their normal condition offer a relatively poor developing medium.

The results of the experiments at this point lead us to the consideration of various abnormal conditions, and to the question as to how far the bacteria may be permitted to infect the yeast by the introduction of these; but, as I have mentioned before, I wish to reserve this subject for a further paper, when certain experiments which I am now engaged upon will have been completed.