MEETING HELD at the VICTORIA HOTEL, MANCHESTER, on Thursday, October 25th, 1900.

Mr. H. Well-Blundell (President) in the Chair.

The following paper was then read by Mr. Norbert Van Laer, discussion ensuing.

The Chilling and Filtering of Top-Fermentation Beers

By Norbert Van Laer

Introduction.

In a paper read before the Midland Counties Institute of Brewing on November 9th, 1897, entitled “Cold and Sparkling Ales” by Dr. H. Van Laer (this Journal, 1898, 4, 24) a discussion ensued, in the course of which two gentlemen made some remarks to which I will first of all refer in the present paper.

The first gentleman mid “That the author had opened up a new subject when he suggested the application of the process practisecl in America to English beers. Carbonating was at present resorted to in the case of certain bottled beers. In his opinion, however, it would take many years to introduce a process involving so many novel and distinct operations– such as cooling, filtering and carbonating, which must produce, moreover, a vast alteration in the national beverage of this country. He though also it would take longer than the author anticipated to get Englishmen to appreciate the altered conditions, seeing that English brewers produced beers by their present method, such as were not exceeded in quality by those made by any other process unless it could be shown that the new process produced a better article.”

The second gentleman said, “With regard to bottled beers their forefathers had been accustomed to long storage, and he believed it would be a long time before they would succeed in overcoming the prejudices of these bottled-beer drinkers. He therefore saw a great difficulty in the general adoption of the carbonating process. Then again, the working classes were accustomed to beers that were well hopped and sparkling, having become conditioned in the cask The adoption of special plant would take so much time and money that he feared the change could not be effected with much practical benefit. It was asking the brewers of this country to undertake a great change in their plant and mode of business, and to cast aside what had been going on with great success for many centuries. Before they could adopt such a radical change they would want to know the cost and what real beneficial results would accrue.”

The first speaker had certainly formed a wrong opinion, for in less than a year the American vacuum system of fermentation was introduced into Burton-on-Trent. With regard to the cooling, filtering, and carbonating of top-fermentation beers, this gentleman was perhaps not then aware that the process was then in operation in England, and that the beer could at that time be obtained at different parts of the country. After having carefully studied this system for some time on the Continent in order to adapt it to English beers, it was not until August, 1897, that I had the opportunity of successfully carrying it out on a commercial scale.

The article put on the market having been much appreciated by the British public—thus proving that the system produces a superior class of beer—a number of brewing firms very soon adopted this method of working.

With reference to the second speaker’s observation, I quite agree with him that our forefathers pinned their faith on long storage for bottled ales. But this has changed since their days, and the public is now more accustomed to a more newly-brewed beer, and consequently to bottled beer which had undergone a shorter storage. The carbonating system has been applied to light dinner ales for many years, and naturally the habitual drinkers of these beers are now used to carbonated beers. Concerning the working class: these are certainly accustomed to beer which has been conditioned in case, and prefer it to any ordinary bottle beers.

The chilling, filtering and carbonation process having thus proved to be of success in this country, I will now rapidly describe the various manipulations, commencing with the rapid chilling.

- The Rapid or Mechanical Chilling.

The rapid chilling of beer as practiced by a number of brewers in this country consists chiefly in passing the beer through a series of cells placed in a specially-constructed tank or cylinder which are cooled by circulation of brine, direct expansion of different refrigerating mediums, or in some cases by covering the coils or recipient with ice and salt and sometimes simply with ice.

In this process the ale can be chilled to a fairly low temperature; the ale if brilliant or bright becomes hazy after having passed through the chilling machine, owing to a partial separation of the bitter hop resins, and to a slight precipitation of glutinous matters.

The machines required for this kind of cooling occupy little space, which is a great advantage to a firm doing a large trade, and having but little accommodation to space.

Although this was of cooling seems at first to recommend itself, there are, nevertheless, many drawbacks, of which I will give a short résumé. Where ale is forced through a great length of metal piping, which is mostly made of copper, tinned inside, the beer, after circulating in these pipes, takes up, at the commencement of each operation, a disagreeable taste resembling metal. Experience has proved that this metallic taste is more pronounced in beers containing preservatives, especially bisulphate of lime.

The beers to which salicylic acid has been added the metallic taste is hardly perceptible, and the peculiar flavour that ordinary salicylic acid beers possess disappears after filtration and carbonating, and even after some length of time in bottle no peculiar taste can be detected.

Another disadvantage of the rapid chilling is that when a special cooling machine has to be put up for the purpose of working the chilling apparatus, the cooling of the ale only takes place when the bring circulates through the cooling vessel, and a serious inconvenience which often occurs with coils is that when the brine or any other circulating medium is at a temperature below 26o F,., the ale gets frozen in the tubes and obstructs the passage; this happens more especially with light-gravity ales.

A great difficulty which has been experienced in the construction of rapid chilling apparatus is prevention of leakages at the ends of the tubes, especially as these are exposed to so many variations of temperature and contraction, which, in many instances causes the brine to escape, and so mix with the ales, of which we can naturally guess the consequences.

Then the system of chilling and filtering was introduced into this country and became well known, many interested in this subject took out patents for improvements in all sorts of chilling machines. I must not omit to mention that I was amongst them, and obtained provisional protection for a rapid chilling machine of my own, taking care during the time it was protected to study the matter carefully, and to see if it would be really a success, before filing the Complete Specification.

In the meanwhile various investigators in this direction brought out patents for other rapid-chilling apparatus. But after more practical experience, I came to the conclusion that the rapid chilling did not answer satisfactorily for English ales, and that the slow process was the best.

- The Slow Process of Chilling

No doubt all of you still remember the very interesting paper read before this Institute on November 11th, 1897 by Dr. Horace T. Brown (“On some Recent Advances in Brewing in the United States,” this Journal, 1897, 3, 474). It is to this valuable contribution I wish to refer in these remarks, and doubtless you will pardon me if I repeat to you a passage in which Dr. H. T. Brown gives some advice on this subject. He says:–,

“All that is required is to store the ale for a week or two, after leaving the brewery, in vats at an ordinary temperature of 55o F. or thereabouts, with the addition of some dry hops, until it is somewhat matured by a natural process of after-fermentation. It can then have its temperature reduced, and pass on to this cold storage vats, and from there be passed through the usual process of carbonating and filtration.

“There are already one or two brewers in the United State who are so far modifying the cold-storage system as to mature the ale previously in the manner I have just indicated, and the result has proved eminently satisfactory. It is on these lines that I would recommend any one in this country to go who may be desirous of giving the system a trial, for without a certain amount of previous maturation by ordinary storage, it is not possible to obtain all those qualities which are desired by a critical public. The combination of the two systems, limited maturation and cold storage, with its attendant filtration and carbonation, give a beer which if consumed within a reasonable time is as near perfection as anything can be.

“My remarks will no doubt already suggest to some of you that the crude plan of carbonating in bottle, as practiced in this country, admits of much improvement on the lines of the process I have described.

“No doubt many of the difficulties which are at times experienced by bottlers of ordinary carbonated ale can be removed by an intelligent study of this new and practical process recently introduced into America.”

These suggestions of Dr. Brown’s, I can only say are being adopted at the present time in the slow process, in which after the beer has been matured for about a fortnight it is put in a cold chamber where the temperature is kept uniformly below 32o F., in order to allow the resinous and other matters to settle slowly. As the beer undergoes a slow chilling, it at the same time becomes gradually bright, and after about a week’s cooling, in many instances, is nearly brilliant before filtration. This is very important, as it is necessary to have the beer bright in order to obtain the maximum amount of filtration without renewing the filtering materials.

There are many advantages due to this slow process, which are too numerous to be dealt with in this paper. I will content myself by saying that this method of chilling has given the best results with English top-fermentation beers.

- Filtration.

Before entering into the particulars of filtration, I will say a few words as to the qualities a beer filter should posses.

The choice of a good beer filter depends on some important factors, and, although several types of filters are at the present day on the market, many of them are not suitable for English beers. A point to which I will call your attention before deciding upon a certain make is the interior o the filter, and the making of the perforated plates and sieves. I have known cases where the plates were made of galvanized iron; the beer filtered thought these filters took up a large proportion of zinc and other noxious metals, which rendered them unfit and dangerous for consumption. We all know that beer contains a certain amount of acidity, which readily set up galvanic action when it comes in contact with two metals. Thus when a perforated copper plate is imperfectly covered with zinc, and any part of the copper remains exposed, the moment the beer comes in contact with the two metals, zinc and copper, a certain proportion of zinc is dissolved and passes into the beer. About three years ago some experiments were made on the Continent in order to ascertain the exact amount of zinc dissolved through this galvanic action, and from the chemical analysis of the beer it was found that the quantity of the zinc was a much as 1·918 grains per gallon.

Of course this amount of zinc is exceptionally high, and would naturally condemn the employment of such filter plates. The use of zinc in the manufacture of filter plates is now practically done away with and replaces by tin. But again, as tin cannot be used for the tinning without a certain proportion of lead, two metals are once more submitted to the action of the beer, with the production of galvanic action, and a solution of a certain proportion of one of the metals, this varying according to the state of the impurity of the tin. A number of brewers having experienced this trouble with their filter plates, the makers have had to change the construction and metal, and have adopted either gun-metal or iron plate without any tinning.

Some other constructors have also tried to make their filter plates of copper covered with a thin coat of silver, but as this process requires a good deal of attention in order that every particle of the plate is covered, and , in addition, these filters are very expensive, they are but ever rarely used. In order to manipulate this filter properly, it is essential that a few points should be carefully attended to.

If the filter is well put together, and if the ale to be filtered is sound, it should filter perfectly brilliant. The ales before filtration should be a bright as possible in order to expedite filtration, as the action must not be too slow or intermittent. If the beer to be filtered is very cloudy, the filtering medium very soon becomes obstructed, thus necessitating constant washing of the pulp. The beer should pass through the filter without fobbing, loss of ale or gas, and without any trace of after-flavour. The construction of the filter must be simple and of easy manipulation. It is necessary that the removal of the filtering material can be effected in a short time in order to wash it thoroughly; great care must be taken to prevent leakages or introduction of air.

The filters working with cellulose as a filtering medium are most in vogue in this country. When a filter freshly filled with pulp is started a stream of water passed in the opposite direction to that which the beer will take serves to clear away the impurities, and should be continued until the water comes out perfectly clear. An almost bright beer will filter quickly, and requires only a small change of pulp, whilst a thick beer will necessitate thicker layers and more pressure to force it through the filter. At the end of filtration the filter should be rinsed by means of cold water sent through it in the opposite direction to that in which the beer circulates. This working should be continued until the water comes out quite clear.

The amount of work to be got out of one charge of pulp depends upon the degree of brightness of the beer under treatment. When a new charge is necessary, filtration becomes very slow, and the brilliancy of the beer is not perfect. The pulp can be used over and over again after being well washed. The pulp is first washed with clean cold water, and for this purpose various machines may be obtained, and are generally supplied with the filter. The majority of these consist of a perforated cylinder containing a rouser, with inlets for the cold and hot water, which is sent through it while is in motion. After the pulp has been cleaned with cold water, it may be soaked in hot dilute soda, followed by another rinsing, and then submitted to a very hot scrubbing and sterilising. For the latter, it is placed in a closed cylinder under a small steam pressure for about thirty minutes to one hour.

The pulp is then cooled by having cold pure water sent through it. After draining it, it is ready for use, or, if wanted to be kept for some time, it may be compressed in cakes in a screw press and placed in a good ventilated room.

A mistake which is often made, but which should be avoided, is to put the pulp into hot water; neither must it be steamed before it is absolutely cleaned by washing in the cold. When the pulp is treated directly with hot water, it becomes very black, and takes up a bad flavour, which cannot be got rid of by several washings.

The filter should never be left in contact with the beer when it is not in use, not must beer be left in the filter overnight as it always takes up a very objectionable flavour, which will spoil a good deal of the first filtrations. Before dismissing this subject I should like to say a few words about filtering materials.

A few years ago Dr. E. Prior stated in the Bayerishes Brauer Journal that a large number of cellulose preparations sold for filling beer filters are contaminated with substances with a soapy or oily smell, and which, when steeped in normal beer, distilled water, or 4 per cent alcohol, impart a repugnant and nauseous flavour of a decidedly oily nature to the liquid. It is therefore advisable for the brewer to test his purchases of the material by picking a small sample in pieces and soaking it in beer for a few hours, and then examining the flavour of the latter, when, if contaminated, he material should be rejected as unsuitable, since absolute (chemical) purity and freedom from flavour are indispensable conditions to its suitability.

Prior has also examined chemically pure cotton filter masses and considers these better adapted to the purpose than cellulose, less pressure being required to force the beer through the mass, and there being less probability of the flavour becoming contaminated, the cotton fibres consisting of almost pure cellulose, and entirely free from taste or smell.

Before giving the advantages to the derived from this method, I will rapidly describe the objections which have been put forward with regard to the quality of the resulting beer.

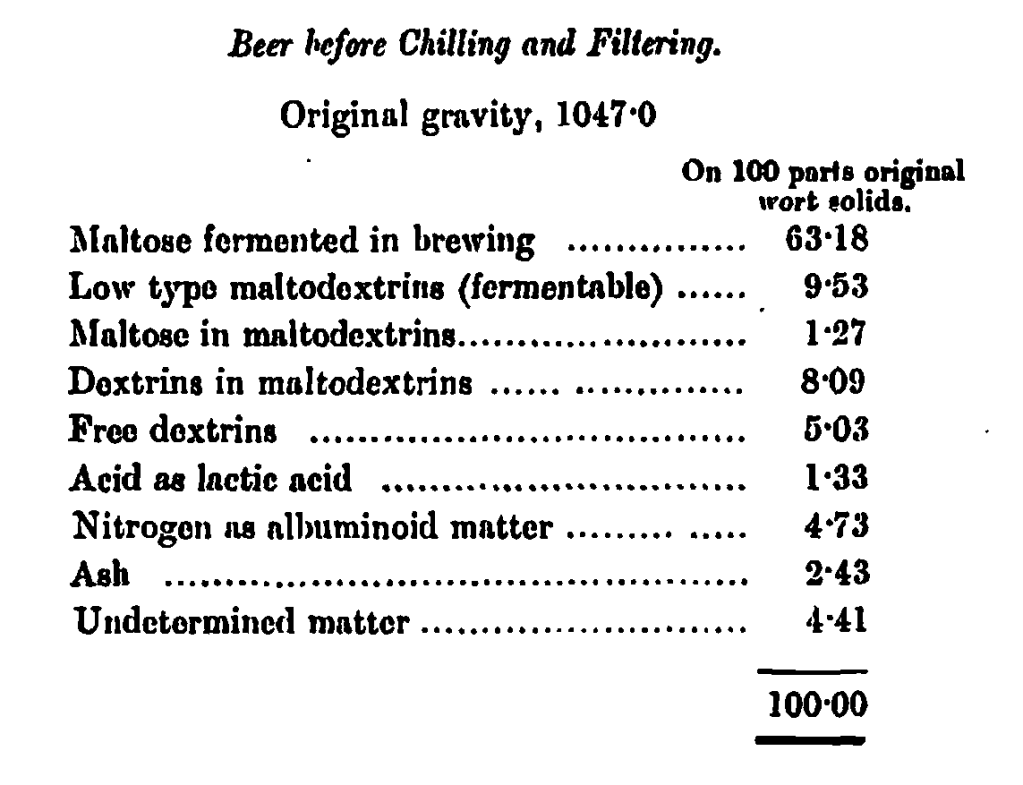

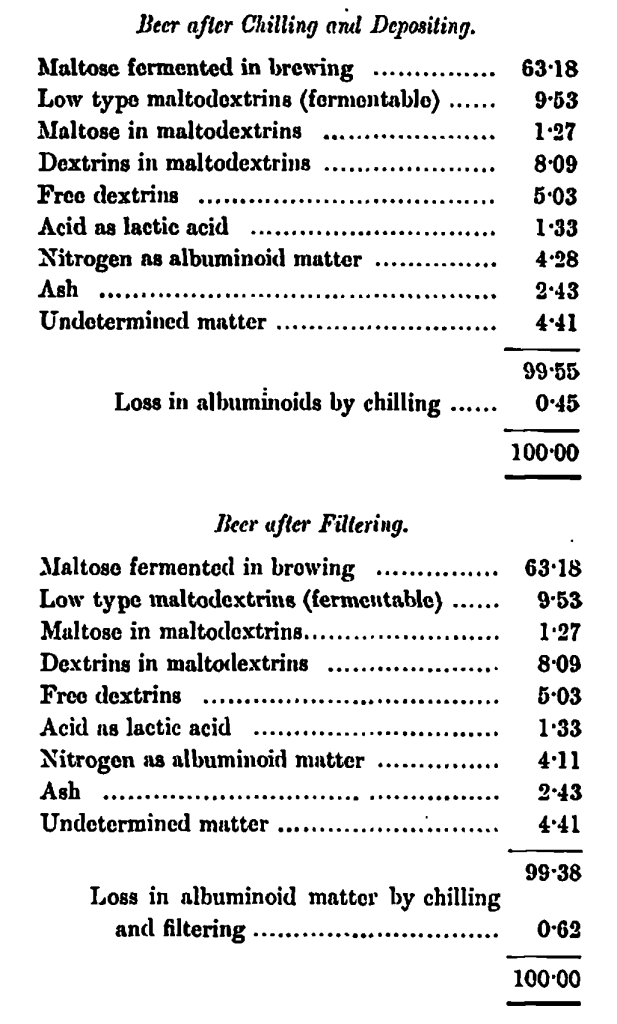

On assertion made is that by chilling and filtration beer loses its fine hop aroma, and drinks like a mild ale; moreover, that the article seems to be of a gravity much below its original strength. Experience has demonstrated that this is an erroneous idea, which I will prove by chemical analysis of the beer. For this purpose, experiments were carried out in the following manner:–

From a gyle of beer two barrels were taken. The first was put into a room at a temperature of about 55o F. until brilliant.

The second barrel was placed in a cold store and chilled for 10 days at a temperature of from 26o to 30o F. At the expiration of this time the beer was very bright. Samples of these beers were taken for analysis with a third sample from the same barrel, but after filtration.

Three analyses were made; the first of the beer in its natural state, the second after 10 days’ chilling, and the third of the same beer chilled and filtered.

The following are the results of the chemical analyses:–

It is seen from these analyses that the quality of the beer is unaltered with the only exception of the albuminoids.

Let me now explain the numerous advantages attached to the chilling and filtering process. The first important point to be considered is the saving of time. I need not tell you the amount of time that is required for beer bottled under the ordinary system to be brilliant and in condition for consumption. We all know the great care ordinary bottled beer wants, and the attention one has to give to it before bottling, also to maintaining a uniform temperature in the stores or cellars. Much space is taken up for storing in bulk, and an enormous room is required for keeping the bottled beer, especially if the bottler has to stock it and bottle only during the proper season for bottling, which is supposed to be from November to June.

As some brewers do not bottle during the summer months, they have a large stock to look after, and should the article not turn out satisfactory the whole of it in some instances may be lost.

In the chilling process no specially large stock is needed; the beer only requires maturing for about a fortnight, then a week’s chilling, then filtering and carbonation, and it is ready for the trade the same day. Thus the time is considerably reduced, large store rooms dispensed with, and bottling can be carried on all through the year. It is during the summer months that the largest business is done in bottled beer; and as the British public is taking to cold sparkling ales, this chilled and filtered beer makes a pleasant, cool beverage for the hot weather, because, being cooled below 32o F., it will stand icing. During the cold winter nights also, when the beer has to be carted away or sent by rail, it will stand changes in temperature during transit which would turn ordinary beer very cloudy, and on arrival as it destination would necessitate it being placed in a warm room until it became bright. In addition to which ordinary beer after having been chilled in bottle throws down a large sediment, which increases the deposit already existing.

You will perhaps object to this process as being rather costly as regards to plant and the working of the same, but I can assure you that the first outlay and the further expenses are largely repaid by the great saving in beer which the old system of bottling is on many occasions lost through turning out unsatisfactorily.

Concerning the loss in aroma by filtration, there is certainly a tendency for this to happen when the hops used are of a very mild and delicate character. Experience has shown that Kent hops are not particularly suitable for beer intended for filtration, and although Goldings have in some instances given very satisfactory results, the employment of a mixture of Goldings and Bavarian, the later of the Halledaus (sic) type, for dry hopping, has given the best results with English beers, the aroma being undiminished by filtration. Thus the trouble due to loss of aroma may be obviated by a judicious selection and blending of the hops.

I very much regret that time and space have not allowed me to say more on this subject, and that I have had to omit the carbonating process, which would have completed the description of the modus operandi of this system.

DISCUSSION

The PRESIDENT asked if any cause had been traced of the tendency to cloudiness which ordinary carbonated beers exhibited. He would like to know if the chilling of beers before filtering would remove the tendency to become cloudy? The purpose of the paper was to show that if the beer was well chilled the tendency to become cloudy afterwards was immediately diminished, if not entirely removed. That being so, what was the matter in suspension that caused the cloudiness? If the ale were free from yeast and bacteria the cloud must be caused by something held in suspension—some form of albuminoids which became visible at a lower temperature. Could the tendency to clod be entirely removed by chilling and filtering? How long would it be necessary to chill beer before the matters in solution entered into a state of suspension and capable of being deposited? What was the effect of different temperatures from freezing point to 40o? Then as to filters, there was galvanic action set up in zinc and iron vessels in the presence of acidity. The author had said something with regard to those and other metals. Most of the best filters were made of copper, and he supposed if they were kept clean they caused less trouble than filters made of other material and produced the best results. With regard to the carbonic acid for carbonizing beers, it was sometimes pumped in at high pressure. Some brewers obtained the carbonic acid gas from the manufacturer; some manufactured it themselves from chalk and sold. He should like to know whether it was a matter of great importance that the carbonic acid should be absolutely pure?

The AUTHOR said that, in the ordinary way of carbonating, the beer was exposed to various forms of cloudiness, of which the most frequent was due to the introduction of air into the beer during the operations. If air became mixed with the beer, a great deal of fobbing would take place, and once this beer was in bottle, turbidity very soon set in. This was a source of trouble which was often overlooked, especially in connection with the filtering process. Another cause of turbidity in the carbonating of beers was due to the employment of insufficiently purified CO2. Practical experience had demonstrated that there was a large variation in the composition of the CO2 put on the market, some of which did not probe suitable for the carbonating of beers. Also, there were beers which could not stand to “gassing” so well as others, this was, perhaps, due to their composition as regards the resins, which the CO2 if not pure had a tendency of rendering insoluble and so producing haziness at the time of carbonating. After two or three days’ standing the beer gradually became bright, with the formation of a slight deposit. When a beer had been properly chilled and filtered, the li9ability to turbidity due to the CO2 was invariably diminished, and as long as the beer was sound and the manipulations were conducted in a right manner the tendency to cloudiness was practically removed. The time which was, as a rule, allowed for chilling under the slow process varied very much, some brewers giving it five days’ chilling, others from one to three weeks. As to the effect of different temperatures from 32o to 40o F., these temperatures were rather too high to produce the required effect. Besides, the precipitation would be very slow and only partial and inefficient. Concerning the employment of copper in the construction of filters, he quite agreed that, as regards the body of the filter, it was very good and could be kept clean; but as to the interior, such as the filter plates, he said that the copper had may disadvantages, and that gun-metal was undoubtedly the best material and most suitable for this purpose. With respect to the question of the modes of production of the CO2, this was certainly of great importance, as the quality of a CO2, adapted for the carbonating of brilliant beers, should be of the purest that could be obtained.

Mr. C.F. HYDE said he had obtained some beer that was supposed to be chilled, filtered, and carbonated on the most approved principle by a well-known firm in this country. When the beer was first examined it was pronounced perfect. The beer was kept in an ordinary office and examined again and again, and the longer it was kept the worse it got. For a quick ale, carbonating was all right; but if the beer was to be kept, then it must be bottled in the ordinary way. The dry hop palate of pale ale was removed by carbonating, and after the process the beer tasted like mild ale. The precipitation of the albuminoids through chilling was very interesting, and he should like to know if the author had determined the amount of hop resins in the beer before and after the chilling by extracting the residue of the beers with petroleum ether.

The AUTHOR, in reply to Mr. Hyde’s remarks, said that he was of the same opinion, that the special type of beer (lager) Mr. Hyde had referred to was not intended to be kept at ordinary temperatures, but only in a cool place. The dry hop palate was partially lost through filtration when hops of a mild aromatic character were used. He was anxious to take up some work in connection with the hop resins in beer, and to estimate the proportion which was lost through the chilling and filtering, but owing to lack of time he had not been able to undertake this operation.

Mr. GLENDINNING drew attention to a paper read before the Institute three years ago by Dr. H. T. Brown, describing the American process of preparing top-fermentation beers for cask by chilling and filtering under pressure. This process had been the outcome of a severe competition, through which American top-fermentation ales had suffered at the hands of the brilliant lager beers. There was no doubt that everything was tending in the same direction in this country, where the growing taste was for new, right, clean, and highly-conditioned beers, and therefore a process like the one under discussion was well worth the serious consideration of all English brewers. He asked the lecturer to what extent the beers were rendered sterile by the process, and also remarked upon the tendency to loss of hop palate in filtered beers. The matter chilled and filtered out was practically all represented in the nitrogenous constituents of the beer.

Mr. BENNETT inquired how long these carbonated beers would keep bright.

The AUTHOR replied, that with the reference to Mr. Glendinning’s question he would say that beer were not rendered sterile by ordinary filtration, unless the beer was filtered through a Pasteur filter, but as a consequence of the severe chilling the action of some species of yeast became to a considerable extent weakened. With regard to Mr. Bennett’s question, the lecturer replied that this naturally depended upon certain factors, that is, if the beer under treatment was sound, well chilled, and filtered, and was kept in a relatively cold room. He had known of its keeping brilliant and practically free from sediment for about three months.

The PRESIDENT asked if the experiment had ever been made of putting a dozen pint bottles of beer, out of the same brew, filtered and carbonated, alongside a dozen bottles of the same brew not so treated? Had the action of chilling and filtering any effect in causing the beer to go bad?

The AUTHOR said that many experiments similar to those mentioned by the Chairman had been carried out on several occasions, and the results were more satisfactory in the case of treated beer than in that of bottled under ordinary conditions. The beer only went bad if proper care had not been taken during the various manipulations to which it was submitted; but the principal cause of the beer turning out unsatisfactorily, was the initial unsoundness of the beer itself.

The PRESIDENT proposed a vote of thanks to Mr. Van Laer for his very interesting paper. He thought the public taste tended more and more towards bottled ales, and was likely to increase in the future. If a good table beer could be obtained at a reasonable cost, the public would be more inclined to it in the future than they had been in the past. If that were to be so, the outlay in bottles would be enormous, especially when losses and breakages were taken into consideration. The subject of the paper was very interesting and he hoped it would be of great service to brewers.

Mr. A. L. LEES seconded the vote of thanks, and said the paper had een so interesting that they could not do better than invite Mr. Van Laer to continue the subject and give them a paper on carbonating beers. After reading the paper in the Journal they might discuss it further.

Mr. HYDE supported the vote of thanks, which was carried unanimously.

The AUTHOR acknowledged the compliment, and the meeting terminated.