MEETING of the MIDLAND COUNTIES SECTION, held at the GRAND HOTEL, BIRMINGHAM, on Thursday, MARCH 23rd, 1922.

Professor A. R. Lind, M.Sc, F.I.C., in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed: —

The Development and Nutrition of Yeast

By Adam Tait, A.I.C., and Louis Fletcher, A.I.C.

The problems connected with development and nutrition are numerous and are of paramount importance if we are to attain an understanding as to the mechanism of growth and maintenance of life. In the vegetable, no less than the animal world, this is true. The complexities involved in the study of the higher forms of plant growth are manifold and in a sense these complexities increase in the lower orders when for instance the size of a single yeast cell is taken into consideration. Daily experience teaches that much happens inside each of these small cells, and when one considers that building up and breaking down processes seem to take place simultaneously the inherent difficulties are easily seen. Thus, it is only possible, in an investigation such as this, to touch the fringe of the subject, but it is hoped that the paper may contain something that will prove suggestive to other workers. Further, when it is considered how great is the number of known species of the organism, each having its own peculiarities and distinctive behaviour under set conditions, the magnitude of the work is enormous. Of course, much has been done already, and there is a good deal of information available concerning a few yeasts.

The very word “yeast” is enough to bring before our eyes the names of men—very famous men—who, by applying their great genius to the study of yeast, have done so much for mankind in the many branches of natural science, and the result of whose work has meant so much to all industries involving fermentation. It is indeed difficult to name any other sphere where an historical sketch would arouse so much fascination in its compilation, or would provide reading so dramatic in its disclosures. We refrain from delving because such would be outside the purport of this paper, and further, the subject is one for more experienced pens than ours. The progress made by the pioneers and their immediate followers was marvelously rapid, but the beginning of the 20th century almost seems to mark a resting stage in the further advancement of knowledge of the subject.

It is not intended to make any further reference to the historical side of the subject beyond mentioning the recent publication of Klocker (Comptes rend. Carlsberg, 1919, 14, 1; this Journ., 1920, 26, 57), as it brings up-to-date in a very lucid manner the available information obtained chiefly by continental workers. Klocker’s work is interesting too, because it clearly shows the marked differences which exist between the functions of the various species of yeast and also the variable manner to which each responds under set conditions.

Although it has been stated that the advent of the 20th century saw a resting stage in the acquirement of new information regarding yeast, it is not to be inferred that there was a complete cessation of activity. Leaving aside the Continent, this country has provided men of talent who have contributed largely to present day information. H. T. Brown, A. J. Brown, and Stern may be said to have carried on the work of the pioneers and applied their information to the brewing industry. Slator and more recently Lampitt are others who have studied yeast from various standpoints. Perhaps the most important yeast is the Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Certain it is that this particular yeast generally controls the destinies of the brewing world in this country. It would seem that included in the designation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae there are several types. The famous Burton yeast and the equally famous Scotch yeast are both classed as Cerevisiae, and yet they possess distinctive characteristics. How far one is justified in assuming a morphological distinction is rather doubtful, having in view some of the earlier work of Hansen. A yeast cell possesses hereditary functions, and yet, as will be shown later, it is a creature of environment. It might be possible to make the above two mentioned types of Cerevisiae exchange characteristics, i.e., make the Burton into Scotch and the Scotch into Burton, in other words, show that they are from the same genus. The importance of pure cultures in all work of this nature is well recognised, but it is as well to draw attention to the possibilities of slight variations being caused by different workers not using cultures from the same antecedents.

In the present investigation, the subject of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, its development and nutrition, is being studied in general, and in particular, with special regard to the brewery types of alcoholic fermentation. Nourishment and growth are admittedly of extreme importance on the practical side, and the problems connected with them are longstanding, and yet it might be said that hitherto the published work has done little towards explaining the difficulties commonly met with, or of adding to our knowledge of yeast behaviour under conditions most important of all—that is, in practice. It is desired to emphasize the fact that unless yeast is cultivated under conditions which permit of a normal growth—normal in the physio logical aspect—it is dangerous and most probably wrong to use the results for generalisations affecting practical issues.

The academic man, or he who is concerned with something other than brewery alcoholic fermentation, may study the behaviour of yeast when grown under conditions which do not approximate to the normal, and he may cultivate the yeast with substances which it would reject were it in a position to indulge in selective nutrition, but from the standpoint of brewery practice it is essential that all conditions are within certain limits which might be termed normal. The question of conditions of experiment is so important that no apologies are made for dealing rather fully with it. There are conditions where variations aro not of much moment, provided they are arranged within certain limits, for example, mineral nutrient and sugar concentration. Stern has shown (Journ. Chem. Soc, 1899, 75, 201), that by doubling the concentration of his normal mineral nutrient the variations in results are such as can be neglected. The normal amount must, of course, contain a sufficiency of those elements necessary to supply the growth of the maximum quantity of yeast. In this connection it is advisable to call attention to the possibility of the lack of proper nutriment when highly purified chemicals and distilled water are used. Yeast ash analyses reveal the presence of traces of certain substances, such as iron and silica, in quantities which cannot be added conveniently, but which may be essential to complete development. If chemicals of commercial purity dissolved in ordinary water are used possible errors from this source are likely to be overcome. In regard to sugar concentrations, the limits within which variations do not affect the main issue aro considerably narrower than the preceding case. It has been found in some preliminary work that a sugar concentration of 10 per cent., i.e., sp. gr. about 1040, is the most satisfactory. It must be pointed out, however, that this concentration, while giving the heaviest yeast crops docs not necessarily produce the best yeast, having regard to numbers and nitrogen content.

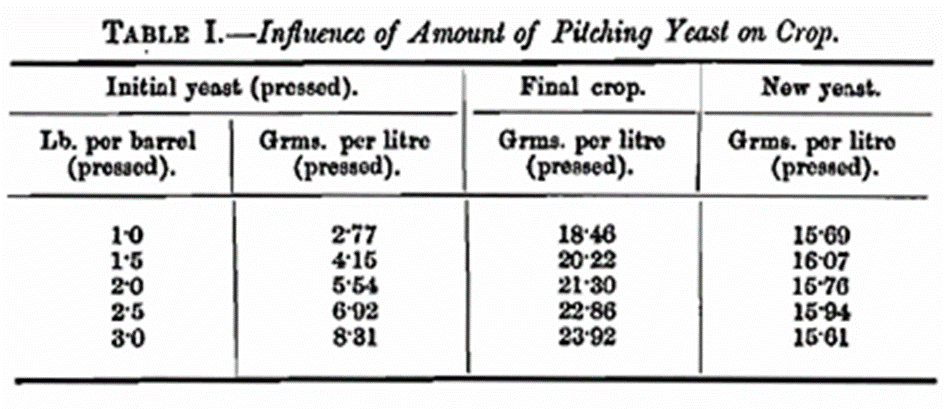

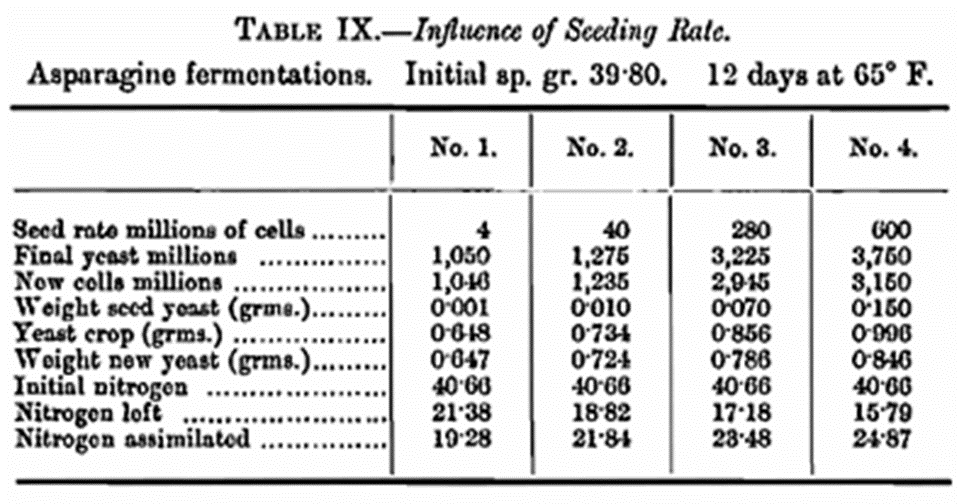

Still more important conditions are those which are governing factors in determining the results of yeast fermentations. These will not be dealt with in order of importance but merely in a manner most convenient for our purposes. Temperature is a factor which has been studied by many workers who have shown its influence on yeast development. In this communication it may be stated that results have been obtained which are in close agreement with those of other workers. All the fermentations have been carried out at 65° F. This temperature has been selected for several reasons. Itis very convenient, easy to maintain, and above all, in the writers’ opinion, the most equable temperature with regard to the whole metabolism of yeast growth. If a higher temperature, e.g., 75° F., is used, then speaking generally it means the introduction of another variable, because such a temperature as this is sufficiently high to have a slight inhibitory effect which is absent or immeasurable at the lower temperature as has been found in some cases during this investigation. The duration of fermentation is another variable which has to be considered carefully and arranged according to the class of fermentation in progress. When it is required to obtain the maximum yeast crop and the removal of the largest amount of nitrogen the maximum time required for laboratory malt wort fermentation with a low seeding rate is about 7 days. In fermentations where asparagine is used as the source of nitrogen a longer time is necessary, about 12 days. The amount of seed yeast employed is a point requiring full consideration. This factor has received attention from previous workers, and, generally speaking, they all arrive at the same conclusion. A. J. Brown (this Journ. 1890, 3, 70) was perhaps the first to show that the new yeast produced when varying seeding rates are used tends to a constant. Such is our experience as will be seen from the results of an experiment carried out in the laboratory with seeding rates within the range of those employed in ordinary brewery fermentations. Five litre portions of brewery hopped wort of sp. gr. 1045 were pitched with ordinary brewery yeast at varying rates ranging from 1 to 3 lbs. of pressed yeast per barrel. After fermentation the total yeast crops were weighed. The results are given in Table I.

The results of this experiment speak for themselves and show that the new yeast produced is practically the same in each instance. In the case, however, of fermentations where the production of substances toxic to yeast is high, the initial seeding rate, at least when low, does have an important bearing on results (see Table IX). It is the considered opinion of the writers that in all experimental work dealing with the metabolism of yeast a minimal seeding rate is imperative. In point of fact a single cell would be the desideratum, but obvious difficulties exclude this ideal. Perhaps this point may be best illustrated by looking at the question from a practical standpoint. In a brewery fermentation, though variations are mot with, the production of two generations of new yeast may be taken as a fair average. Reference may be made to the work of Thorpe and Brown in this connection when compiling the Original Gravity Tables (this Journ., 1914, 29, 569). When a brewer uses a change of yeast, he should not therefore expect that his change is necessarily going to give the desired results in the first fermentation or even the second. Several generations are necessary before a yeast can acclimatise itself to altered conditions. This remark applies to variations in the constitution of the wort. In experimental work where a seeding rate of, say 8,000,000 cells per 100 c.c. is used the number of now generations is something like 9·7 (see Table XV). This will be referred to more fully later. Another factor of great importance and one which has not been given the attention it requires is the shape of the vessel in which the fermentation is carried out, as this has been found to play an important role in laboratory fermentations. We have made a number of experiments which provide interesting data and food for reflection, but it is not intended to include these in the present paper. In all the work under consideration here, 300 c.c. Erlenmeyer flasks have been used, and this might be called the “standard” flask. To make a complete study of the influences exerted by all these factors separately and collectively will be a lengthy procedure and will involve their differentiation. The information to be gained is so valuable that we intend to carry out further investigations later.

The question of nitrogenous nutrition has been left purposely till the last because it is undoubtedly the most important factor governing yeast growth. Probably the most-quoted publication on this subject is that of Stern (loc. cit.) to which wo have already made reference. Stern’s results, with the artificial nutrients he employed are so much at variance with everyday practical observations that we were forced to conclude that they are abnormal and are in fact controlled by some dominant factor other than any of those specified. It should be stated that Stern in some later work (this Journ., 1899, 5, 399; 1902, 8, 690; Journ. Chem. Soc. 1901, 49, 943) obtained better yeast crops and a greater assimilation of nitrogen when he employed substances other than asparagine as the source of nitrogen. It was the realisation of these divergences, corroborated by a close study of the amount of nitrogen assimilated and the yeast crops obtained in fermentations with asparagine when compared with malt wort fermentations, that led to an attempt to find some explanation of the differences observed, and it was mainly with that object in view that the present work was under taken. A quotation by A. J. Brown in some work with asparagine (this Journal, 1890, 3, 70) is interesting from the fact that it was made more than 30 years ago.”. . . . The experiments with asparagine, quoted above, and other experiments I have made, lead me to think that an excess of this body is even deleterious to the growth of yeast . . . .”

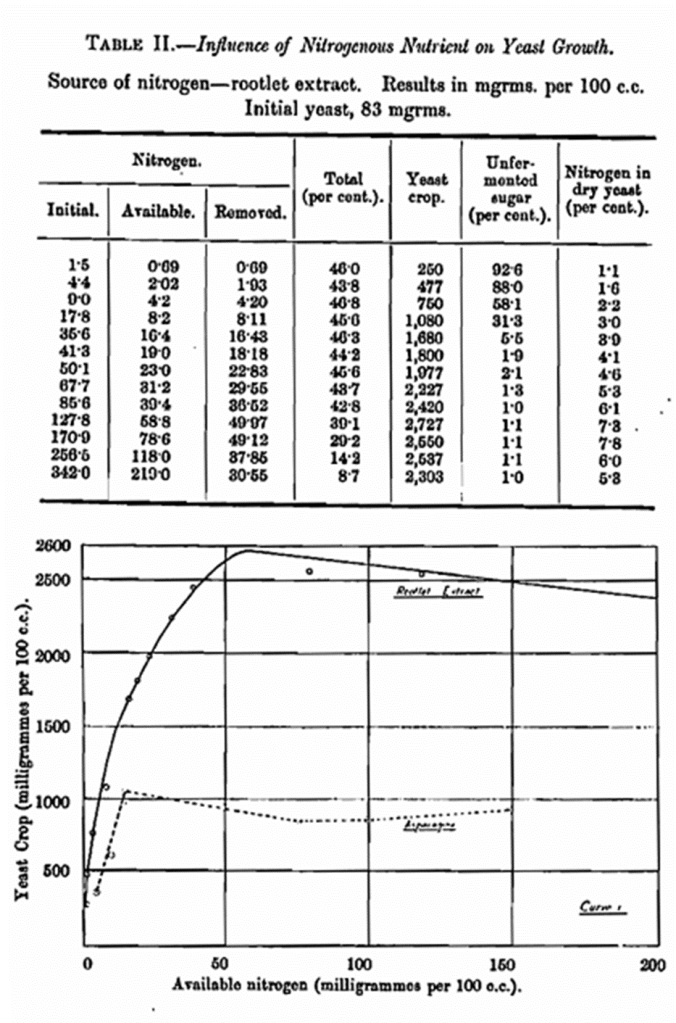

The most suitable forms of nitrogenous matter for brewery yeast development are those found in malt wort, but it is obvious, in an investigation on the influence of nitrogen alone, that it is somewhat difficult to arrange the experimental conditions using malt worts, so as to have the nitrogen-content the only variable. A simpler method and one which was thought to be open to few objections, is to prepare a concentrated extract from malt rootlets. In this way a highly nitrogenous extract composed of practically the same substances as those in malt worts is obtained. This nitrogenous extract was added to an invert-sugar solution which contained a sufficiency of all the mineral ingredients requisite for the proper development of the yeast. The separate solutions, 100 c.c. in volume, so prepared wore sterilised, aerated by standing 24—48 hours, and seeded with a 48 hours’ culture of pure Saccharomyccs cerevisiae, which had been washed by decantation with sterile water. In this particular instance the amount of seed yeast was 0·083 gm. The fermentation was carried out at 65° F. for seven days. The results are given below in Table II, and also expressed graphically in Curve 1.

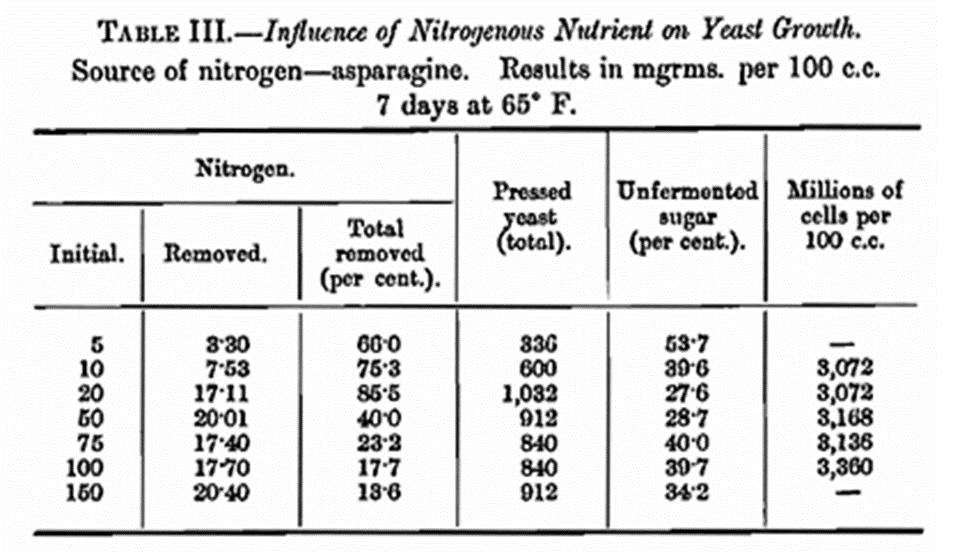

In Table III are given the results of a set of experiments where the solutions were composed of invert-sugar, mineral nutrient (Stern’s mineral nutrient B.) and asparagine. Throughout this work natural asparagine (β—1—asparagine) was used, and incidentally we confirmed Bresler’s solubility constants at 60° F. (Zeitschr. physikal. Chem., 1904, 47, 611).

It will be seen that the results with asparagine are in harmony with those obtained by Stern (loc. cit.). The figures detailed in Tables II and III are startling in their differences. Those in Table II compare favourably with those obtained in wort fermentations and therefore might be called quite normal so far as brewery fermentations are concerned. The asparagine results on the other hand are entirely abnormal and show how misleading it is to draw general conclusions from such experiments. The search for reasons responsible for these discrepancies has occupied a large portion of the time devoted to this work.

Fermented solutions of sugar and asparagine are acid, the hydrogen ion concentration of the solution in some cases corresponding to approximately a pH of 3·5. Yeast, we know, is unable to reproduce itself at this acidity. A series of experiments with asparagine were followed by a daily microscopical examination of the yeast. After the first day or two the cells assumed an abnormal appearance. The new cells were smaller than the parents, having obviously reached maturity without acquiring the same dimensions as their progenitors, and the shape of the cells was not quite round. As fermentation progressed an increasing number of dead cells, as shown by methylene blue staining was observed, this including a heavy mortality among the buds. This is ample proof of the difficulties under which the yeast grows under such conditions and how it appears to lose vitality with each succeeding generation. The toxic effect we attribute to the production of acid. In Table III it will be noticed that increasing the nitrogen beyond 20 mg. per 100 c.c. leads to a diminution in the yeast growth, the fermentations are incomplete and the number of yeast cells produced is actually the same in each case, the numbers, however, representing poor reproduction as can be soon by comparing the results with those in Table IV.

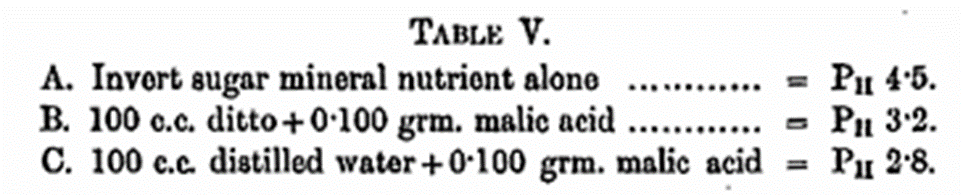

Growing yeast in its search for nitrogenous food breaks down asparagine with a final production of malic acid and this acts as a poison, suppressing and finally inhibiting reproduction as soon as its acid concentration reaches a certain limit. The manner in which malic acid increases the hydrogen-ion concentration of solutions is recorded in Table V, which shows the effect of adding 0·100 gm. malic acid to 100 c.c. invert mineral nutrient solution of 1040° and also to water. 0·100 gm. of malic acid is produced by the breaking down of 0·100 gm, of asparagine during fermentation.

It has been shown already that at the termination of an invert sugar fermentation with asparagine as the source of nitrogen the pH value is in close proximity to that of B in the above table. Malic acid then may be said to be a poison in virtue of its acid properties. These remarks and explanations regarding the abnormal fermentations resulting from the employment of asparagine as a source of nitrogen apply to certain of the experiments mentioned in Lampitt’s valuable and comprehensive paper (Biochem. Journ., 1919, 13, 459). We have already indicated this in the Annual Reports of the “Progress of Applied Chemistry’ Vol. 5, 1920.

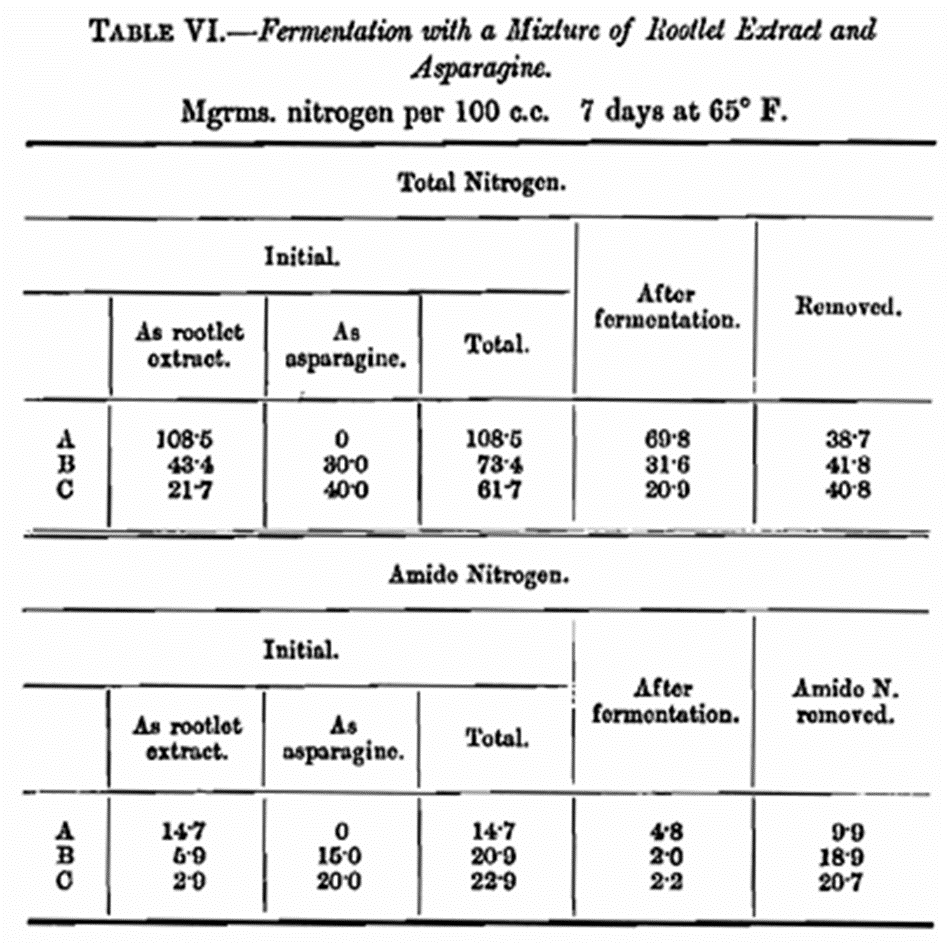

When asparagine is used in conjunction with other amphoteric substances it is found that it is possible for yeast to assimilate more nitrogen. Evidence of this was provided when fermentations were carried out with a mixture of asparagine and rootlet extract as the source of nitrogen. The results are set out in Table VI where the amide as well as the total nitrogen was determined.

Only 46 per cent, of the nitrogen as rootlet extract is assimilable (see Table II), so in the case of C this amount is 10·0 mg. As the total assimilated is 40·8 mg., the amount removed as asparagine is 40·8-10·0 = 30·8 mg., an amount greater than that removed using asparagine alone. Another experiment was conducted with a mixture of rootlet extract and asparagine to see, if by adding more sugar at certain periods, it would be possible to remove more nitrogen. The volume of A was 100 c.c. and that of B and C 80 c.c. and 90 c.c. respectively. At the end of 7 days the nitrogen and yeast were estimated in A. To B was added 20 c.c. of a concentrated invert sugar solution, and to C 10 c.c. of an invert sugar solution of twice the strength, each being equal to the addition of about 5 gm. invert sugar. After a further 7 days, B was treated as in A. To C was added a further portion of 5 gm. invert sugar, and after another 7 days treated as A and B. The results are given in Table VII.

It will be observed from Tables VI and VII that it has been possible to remove about 30 mg. of nitrogen as asparagine per 100 c.c. Similar experiments have confirmed these results. There are obvious objections to these experiments because of the complicated nature of the amphoteric substances contained in the rootlet extract. A further attempt was made to supply potential basicity in a simple way, avoiding these complications as far as possible, by carrying out a series of experiments in presence of calcium carbonate and a parallel series without such addition. It was thought that the malic acid produced from the asparagine would be neutralised as it was produced, thus over coming its deleterious effect on yeast production. The results are set out in Table VIII.

It has been stated previously that in asparagine fermentations where the initial seeding rate is small a marked influence on the final results is observed as shown in Table IX. Accordingly, the fermentations with and without calcium carbonate were carried out using two distinctly different seed rates.

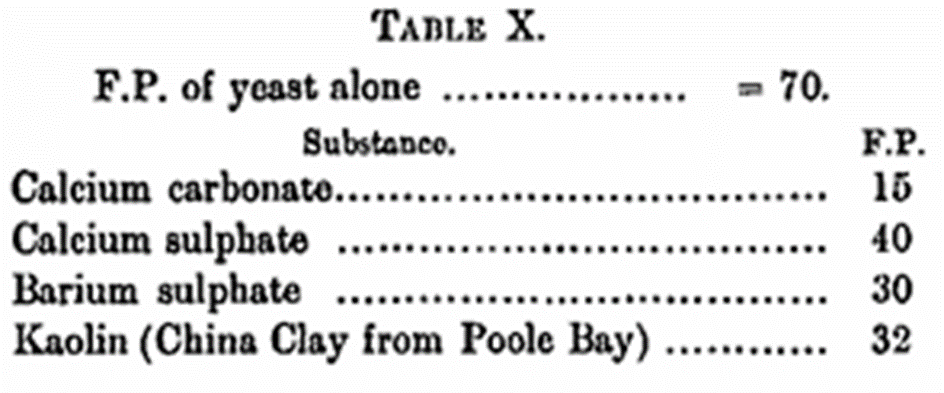

While the results show that calcium carbonate favourably influences nitrogen assimilation and yeast development in a slight degree, the results are somewhat disappointing and not as were expected. It will be seen that in all cases where the carbonate was not used the final Pu of the solutions was, with one exception, 3·5, while in presence of the carbonate such a degree of acidity was not attained in any instance. While it is difficult to find a suitable explanation for the comparatively small favourable influence of the presence of calcium carbonate, further experiments have shown that part of the cause, at any rate, is due to a mechanical clogging of the yeast with a possible diminution of the diffusion surface. This was proved by determining the fermentative power (F.P.) of yeast in the Slator apparatus, using an amount of carbonate in the same proportion to the yeast as in the original fermentations. It will be seen from the results in Table X that the mechanical clogging effect is a property shared by other substances.

In the case of the last three substances the effect is probably purely and simply of a mechanical nature, but the calcium carbonate does not admit of quite so easy an explanation. An examination of the liquid after the experiment revealed a considerable quantity of calcium bicarbonate, as would naturally be expected. That this salt is going to have some influence on the internal mechanism of the yeast is also to be expected, and it is highly probable, as indicated by a comparison of the above fermentative powers, that its influence goes to the retardation of the zymatic functions of the cell. That the presence of insoluble substances does exert some influence on the rate of fermentation is evidenced by a further experiment with malt wort with and without the addition of calcium carbonate, the result of which is given in Table XI.

The question of potential basicity is of such fundamental importance and far-reaching significance in its application that a résumé will be made of the experimental work carried out in the attempt to prepare a nutrient containing a sufficiency of soluble potential base. At first sight the idea of using calcium carbonate appeared quite sound. It is an almost insoluble salt, easily amenable to the action of acids, apparently innocuous to yeast growth and would appear to be able to neutralise an unlimited amount of acid. As an agent for removing acidity from solutions in biological work it is not new, but in view of the results detailed in this work it may be necessary to reconsider these other figures from the fresh aspect. It is well known that calcium hydroxide combines with certain sugars to form quite definite additive compounds. It was thought, therefore, that invert sugar might combine with sufficient lime to provide a supply of soluble base. This surmise was correct, for an invert sugar solution of sp. gr. 1080 is capable of dissolving a very considerable amount of lime added in the form of a cream of freshly slaked CaO. The solution eventually prepared contained double the amount of lime required to neutralise an amount of malic acid possible to be produced from 0·200 gm. asparagine during fermentation. Certain difficulties were met with in its application. For example, a flocculent precipitate was thrown down when the prepared invert sugar solution was added to the mineral nutrient. This proved to be calcium phosphate. However, by adjusting the pH to 5·0 with lactic acid a clear solution was ultimately obtained. The salt part of it was virtually a solution of calcium lactate, but this was proved to be possessed of decided basic properties. Malic acid was added to a small volume of the solution in the same proportion as it would be formed if all the asparagine present was broken down to malic acid. The pH was reduced to only slightly under 4·0 whereas the same weight of acid added to the untreated invert sugar nutrient solution reduced the pH to about 3·0. The results were the same as previously obtained in other asparagine fermentations. Nothing further was done at the time, because better things were expected from the calcium carbonate experiments, and further, because the full significance of the question was not quite realised.

It has been shown unmistakably that the production of acid is in itself sufficient to cause a serious retardation of yeast activity, but it is equally obvious that there must be other factors which play their part in this suppression. A natural assumption is that ammonium salts are not suitable for this particular type of Saccharmyces cerevisiae. This opinion has long been held by many eminent workers regarding Saccharomyces cerevisiae despite the statements emanating chiefly from the Continent that ammonium salts are quite satisfactory as a source of nitrogen for yeast Lampitt (loc. cit.) has shown that ammonium malate is assimilated by yeast, which of course must be the case if it is an intermediary product in the decomposition of asparagine by yeast. Although details have not been given one of the points proved early in the course of this work was the presence of ammonia and malic acid during an asparagine fermentation. In a certain fermentation industry ammonium sulphate is the only nitrogenous food used for the particular organism employed and the results are excellent. What is good for one yeast can quite well be a poison to another. Just in the same way Klocker (loc. cit.) shows the preference of different species of yeast for particular sources of nitrogen and also the degree of acidity which the yeast will tolerate. But why go outside your own brewery to gather this information? It is well known that the general run of beer diseases is due to wild yeasts and bacteria and the reason is usually that the beers have developed so much acidity that the culture yeasts have weakened. These wild yeasts, aided by this weakness and coupled with the important fact that the particular degree of acidity which accounted for suppression of the primary yeast is probably quite favourable to their own development, have flourished.

Pursuing the investigation a step further many salts of weak acids were tried with varying success and failure. One fact to be borne in mind and one which precluded the use of some salts which otherwise appeared satisfactory is the desirability and perhaps necessity for keeping the salt concentration as low as possible. The most promising salt among those tested was sodium lactate. A 10-per-cent. solution was prepared by boiling the necessary amount of lactic acid with water and sodium hydroxide till no further consumption of alkali took place. It is necessary to boil with alkali instead of the usual simple neutralisation in the cold owing to the possible presence of lactic anhydride. The pH of this solution was 9·0. The usual nutrient containing asparagine was prepared so that it contained 1 per cent, sodium lactate. As prepared, this gave a pH value of 7·0—7% and 100c.c. required 4·0 c.c. N/l HCl to bring the pH to 4·0; 4 c.c. N/l HCl=4 x 66 =264 mg. malic acid, which is much more than is produced in an ordinary asparagine fermentation. A brewery wort was taken and to it was added the same amount of sodium lactate and the pH adjusted to 7·0. As a further comparison the same brewery wort untreated was employed. The results are given in Table XII.

From the results of the foregoing experiment, it is first observed that the pH of the final solution varies from 4·2 to 5·5, a condition which may be considered normal. Therefore, production of acid in itself is not the cause of the asparagine fermentation giving such poor results, for it is noticed that, while the asparagine and the wort had initially the same H-ion concentration, the wort is now more acid, and, since the potential basicity in the wort is very much greater than in the asparagine nutrient, the inference is that a larger amount of acid has been produced. The yeast crop from the asparagine is of the usual poor weight, although a microscopical examination showed that the yeast was quite healthy and had a lower percentage of dead cells than usual, while both worts yielded normal crops. Incidentally the value of sodium lactate as a soluble potential base, in virtue of the low dissociation of lactic acid, is worthy of recognition and might with advantage be employed in other fields of research.

A considerable amount of time and labour has been expended on the work dealing with asparagine fermentations, and to some it may appear to be of unnecessary length. The evidence gained by the preliminary experiments was sufficient to prove amply that asparagine is not a suitable food for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The subject was pursued further not as one of the many interesting and tempting side-issues always connected with chemical and biological research but because it was recognised as having a distinct bearing of primary importance on many of the troublesome phases in beer production. A little reflection will show the truth of this remark. Under certain circumstances it happens that a beer contains an excessive amount of amino-acids. Such conditions may arise, for example, from the use of “slack” or “forced” malt and it now becomes evident why under these conditions the beer is of poor flavour, thin and of lowered stability.

Reverting to hydrogen-ion concentrations which have been mentioned so frequently during this paper, it is now well known that this subject is of great value in all fermentation investigations. It is undoubtedly a most valuable tool but at the same time it is one which is very difficult to use correctly. To begin with it must be borne in mind that the determination of the hydrogen-ion concentration is merely a measurement of an equilibrium and as such it is apt to be misleading. To illustrate this point it is quite an everyday occurrence to have two or more beers of the same pH value, but it does not follow that those beers will be of the same quality or have the same stability. The question of taste has not been mentioned but it may be pointed out in passing that the hydrogen-ion concentration is not a measure of the physiological sensation of sourness as it is well known for example, acetic acid at certain dilutions tastes much sourer than a mineral acid solution of the same concentration. This is probably due to the anion of such organic acids having an acid taste. We have laid much stress on the question of potential basicity throughout this communication as we are of opinion that this will unquestionably have a great influence on the resultant pH value of a beer. This, in effect, is a plea for the necessity of supplementing the hydrogen-ion concentration determination by some other measurement. Attempts have been made by Emslander (this Journ., 1914, 20, 555) and others to estimate the acidity of beers electrolytically. This is a step in the right direction because it will show any difference in beers which may have the same pH value. We do not agree with Emslander’s method of determining real neutrality; he assumes that a simple proportionality holds but this is obviously impossible in view of the complex dissociation phenomena involved. We have proved experimentally that in order to estimate the real acidity of a beer it is necessary to mako more than two determinations of the hydrogen-ion concentration with varying additions of alkali. By plotting the results and observing where the graph cuts the line of neutrality, pH 7·07, a measure of the acidity can be obtained. By this method it is possible to get indirectly a measure of the potential basicity in beer and this, in conjunction with other factors, throws valuable light on the keeping qualities of the beer. This is perhaps of special value in the case of export beers where the time of storage is generally prolonged, but used judiciously the information can be applied to ordinary beer as well. We may appear to have wandered from the main subject of our paper but these last few remarks really arise from the influence of acidity on yeast development, and we have tried very briefly to focus the importance of the question of hydrogen-ion concentration in brewing research. In a number of experiments dealt with throughout this investigation it will be seen that the amount of nitrogen removed during fermentation has been given. We are well aware that in estimating the nitrogen before and after fermentation the difference does not necessarily represent the nitrogen assimilated, because the yeast may excrete a certain amount of nitrogen. We ourselves are of opinion that in the case of small seeding rates it has not been established that growing yeast does excrete nitrogen in the true physiological meaning of the term. Further, we have found from experience that the estimation of the assimilable nitrogen, i.e., difference in nitrogen before and after fermentation, in malt extracts and brewery worts, is very valuable in practical brewery control. It is reasonable to expect that this would be even more valuable if a fair percentage of malt substitutes was used in compounding the grist whereby a diminution of the nitrogenous yeast food would naturally occur. These few remarks anent the nitrogenous food supply only help to emphasise further what has been said already regarding the great importance of this factor in yeast growth.

In Table II the percentage of nitrogen present in the dry yeast grown in various solutions is given. These range from 1·1 to 7·8. Wo must therefore have produced yeasts of varying functional capacities. Considering simply the fermentative power of such yeast how would they compare? From the data available it is possible to prepare quantities of yeasts of the nature required and by curtailing the duration of the fermentation it was found possible to obtain yeasts with considerably higher nitrogen-contents than 7·8 per cent. In Table XIII the fermentative powers of a number of yeasts so prepared are set out and also given graphically, in Curve II.

In connection with the determination of the fermentative power of yeast, the method used was that worked out by Slator (Journ. Chem. Soc.9 1906, 89, 128). The actual details of the determination in this work were as follows: — 0·6 gm. washed pressed yeast (the variation in moisture content of pressed yeast is such that any difference was neglected.) was weighed out and washed into a wide-mouthed stoppered bottle of about 250 c.c. capacity containing 50 c.c. of a 5 per cent, sucrose solution and about thirty small glass beads. The total volume of sugar solution and washings was adjusted to 70 c.c. The temperature throughout was maintained at 30° C, and eight to ten readings were taken at 5-minute intervals. The average fall in centimetres per 5 minutes, multiplied by 100, represents the fermentative power (F.P.) of the yeast. In the particular apparatus employed a fall of 1 cm. is equivalent to the production of 0·0100 gm. CO2, starting with an initial internal pressure of 5 cm. (These details are given in order that the results may be compared by other workers should they be required.)

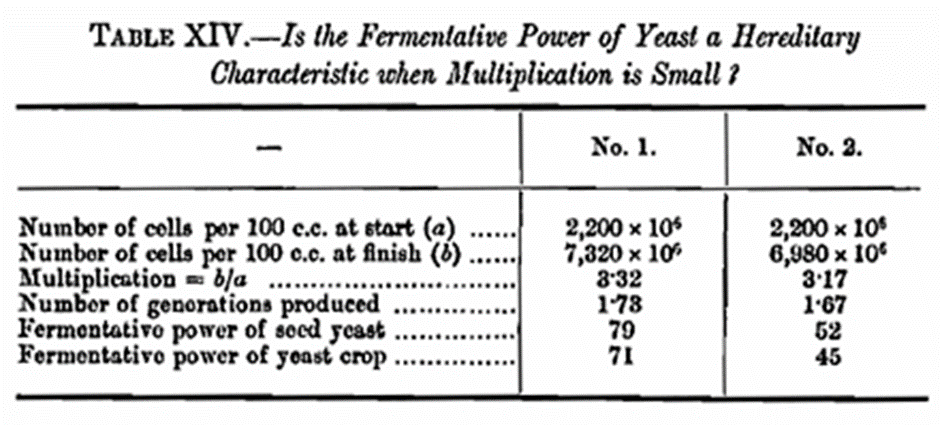

As will be seen from Table XIII and Curve II there is a distinct relationship between the nitrogen-content and fermentative power of these yeasts, and this observation is of important practical value. If two portions of the same wort are pitched with equal quantities of two yeasts of the same species of high and low fermentative power then the resulting crops are found to exhibit to a considerable degree the parental fermentative characteristics. The high fermentative seed yeast gives progeny with a higher fermentative power than that of the low seed yeast, even though the medium may be such as to give rise to yeasts of greater or less fermentative energy. This suggests reason for the belief as to the value of “strong store” or a “change of yeast“ in practice. The result of an experiment in support of these remarks is given in Table XIV.

When one comes to consider this matter, the result is not surprising. Under practical conditions, as stated before, there are produced about two new generations, so that continuity of the cell plasm will be fairly marked. It seemed worthwhile to find out if the apparent hereditary fermentative power would be exhibited when a much greater number of generations was formed, and an experiment was arranged to test this. Two yeasts of dissimilar fermentative powers were prepared, and two portions of the same wort were seeded with a small and equal number of cells of each yeast Fermentation was carried out at 65° F. for six days, at the end of which time the fermentative powers of the crops were determined and the following results were obtained.

The apparent heredity observed in the previous case with the higher pitching rate has thus been duo to the limited number of generations formed under such conditions. Indeed, the mere possibility of growing crops from the same seed yeast, with such dissimilar fermentative powers as those in Table XIII, shows that the hereditary functions can only be confined to a few new generations.

Although there are many factors governing the metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisim9 and some of these have been set out only very briefly, we have produced sufficient evidence to summarise the main features of this contribution on the subject of development and nutrition of yeast. Among other things we have shown—

1. The importance of working under set conditions depending on the type of fermentation under examination.

2. The very poor yeast development and nitrogen assimilation when asparagine is used as the source of nitrogen when compared with practical brewery observations, and also the toxic effect of the products of the action of yeast on this amide.

3. The influence of acidity on yeast growth and the importance of potential basicity.

4. The value of the hydrogen-ion concentration in brewing.

5. That ammonium salts do not appear to be good yeast foods for S. cerevisiae.

6. The relationship between the fermentative power and nitrogen content of yeast under certain conditions.

7. That there is a distinct relationship between the initial nitrogen content of worts and the amount of yeast produced, at least at the lower nitrogen concentrations.

In concluding this part of the investigation on the development of yeast we would like to say how fortunate we have been in having the benefit of the long experience of Mr. J. S. Ford. It is therefore with much pleasure that we record our best thanks for his general supervision throughout this work, and particularly for the suggestions he made during our endeavour to surmount the many difficulties encountered in the work on the question of potential basicity.

Discussion.

The Chairman said that they had listened to a most valuable contribution, both from the scientific and practical points of view. It gave them much food for thought and would require time for study. At the same time, he hoped that would not debar members present from taking part in the discussion or asking questions of the authors. He called upon the President of the Institute, Mr. Field, whom they were all glad to welcome, to open the discussion.

Mr. H. E. Field said, as a brewer, he realised that they were dependent upon their yeast for the excellence of their productions. Weak yeast was probably the source of more than half the troubles from which they suffered. Therefore, the more information they could get about that valuable commodity the better for them. The Institute was very much indebted to Messrs. Tait and Fletcher, and members would read with interest and profit the valuable contribution which they had heard that night.

Mr. W. Waters Butler referred to Table I, column 1, and inquired whether it was pressed yeast.

Mr. Tait replied in the affirmative.

Mr. Butler added that in the final column it was shown that practically the same crop of new yeast was obtained. He had often wondered whether it was an advantage or otherwise to use a low pitching rate or a high one. If they got the same amount of new yeast when using I lb. per barrel as when using 3 lb., there must be a different rate of reproduction, and it was possible that cells reproducing at a lower rate were stronger and better for future use. Another consideration which inclined them to favour a low pitching rate was that if 1 lb. per barrel was as effective as 3 lb., the smaller amount was more desirable, inasmuch as they would be introducing into the wort one-third of the contamination than when using 3 lb. Something had been said as to the value of using changes of store yeast from outside sources, but, candidly, he was not in favour of it. He instanced the case of yeast used 1,980 times over a period of about twenty-two years, and asked if that yeast was necessarily poorer today for such repeated use than when it was introduced into the brewery. When did the original cells disappear? In his over-twenty-year-old yeast they might say that there was not one of the original cells left in it. Passing on to Table XIV, Mr. Butler said it showed that where there was a low number of generations produced, 1·73, the fermentative power of the seed yeast used was 79 and the yeast crops 71, it gave him the impression that the crop there was practically as strong as the original seed yeast. In Table XV, however, where they went in for a high multiplication and the fermentative power of the seed yeast used was 115—stronger than that used in Table XIV—whilst that of the crop had dropped to 55, as against the one in Table XIV, which started at 79 and ended at 71. He was confident that the paper was a most valuable one, and he hoped the authors would continue their investigations, and that members might later on have the benefit of them.

Mr. Holden inquired why the authors had departed from the ordinary sodium acetate buffer in favour of sodium lactate. He also at a pH of 7·5 rather than at 5. asked if calcium carbonate, used in excess, would function as a buffer

Mr. Price asked if the shape of the fermenting vessel had any influence on the character of the fermentation.

Mr. Sawbridge asked whether the pH value was determined electrolytically or colori-metrically.

Mr. W. Scott enquired how the number of generations of the yeast cells had been arrived at. Most brewers, he said, knew with more or less accuracy what their reproduction was, and he thought his own method was accurate and practical. The total amount of pressed yeast used for pitching was deducted from the weight of the total outcrop (also in the pressed state) each week, thus giving the weight of new yeast produced. If this result was expressed as so much per standard barrel by dividing by the number of standard barrels brewed in the same period, valuable information was obtained as to the relationship between the available nutriment and the yeast reproduction, but this was a different matter to being able to state how many generations of yeast there had been. As to Dr. Slator’s theory that air was not

necessary to a fermentation providing the CO2 was removed, he would like to ask if Mr. Tait had any experience of this matter on a practical scale. He (Mr. Scott) had conducted a fermentation under a 10-inch vacuum without any aeration, but when about half gravity was reached the attenuation entirely stopped so that it was necessary to resort to aeration.

Mr. Smith said he was pleased to hear it mentioned in the paper that forced and slack malts were prejudicial to growing and reproducing yeasts, a point which was very often overlooked by maltsters and brewery directors. Ho asked whether the rousing of beers by the usual motor driven pump method had any tendency to damage the yeast cells and stop the rate of reproduction.

Replying to the discussion, Mr. Tait, in answer to Mr. Butler, said that in Table I the figures given represented the production of about 5¾ lb. of pressed yeast per barrel in each case. As regards changes of yeast ho (Mr. Tait) did not think brewers as a rule liked them.

Mr. Butler interposed to call Mr. Tait’s attention again to Table I, and to ask which yeast he would prefer to use, yeast derived from the pitching with 1 lb. or 3 lb. per barrel. He mentioned that years ago he did some pitching experiments often with as low as ¼ lb. per barrel on the theory that the less seed yeast he used the less contamination he was adding to the wort. He was speaking of beers of nearly standard gravity, and although he got through and with a low temperature, he began to get nervous as to whether a high reproduction was not dangerous

Mr. Tait, in reply, said that a great deal depended on the constitution of the wort. He added that where they had a small number of generations produced the cell plasm persisted in the daughter cells. In Table XV (No. 2) they had yeasts with fermentative powers of 65 and 55. Supposing that the fermentative power of the pitching yeast had been 35 instead of 65, in all probability the final yeast would have been 55 just the same, because the initial seed yeast was almost entirely eliminated in a case such as this where the multiplication was very great. If they were running from day to day with the same gravity wort the only difference that would arise from starting with a small amount of yeast would be that they would get newer yeast for their next brewing. The fermentative power was more or less dependent upon the character of the wort. In reply to a further question by Mr. Butler regarding the age of a yeast cell, Mr. Tait could not express a definite opinion on this point but he did not think the life time of a yeast cell was very long. Replying to the question by Mr. Holden,

Mr. Tait stated that sodium lactate was used as they did not think that the liberation of acetic acid would be good for the yeast and so they did not use sodium acetate. With regard to calcium carbonate in excess, they found the pH was reduced to 5·0 or 5·5. They would like to ask Mr. Holden if his pH value of 7·5 was found after fermentation.

Mr. Holden said it was used for buffering a bacillus which could not grow on the acid side of 7·0.

Mr. Tait said he could not explain the result.

Replying to Mr. Price regarding the shape of the fermenting vessel Mr. Tait explained that they had carried out a great number of experiments with every conceivable shape of glass vessel. Sometimes the yeast came to the top and sometimes it went to the bottom. Sometimes they got big and sometimes small crops. All they said was that the results gave food for reflection and thought. If he (Mr. Price) was referring to round vats or square vats he (Mr. Tait) did not think it should make any difference in practice with big quantities. He did not think rousing would have any effect in breaking up the yeast. Mr. Tait stated in reply to Mr. Sawbridge that the hydrogen-ion concentrations were determined by both methods, generally electrolytically sometimes colori-metrically.

On the proposition of the Chairman a vote of thanks was accorded to the authors for their very interesting and important paper.