MEETING of the SCOTTISH SECTION held at the CALE DONIAN STATION HOTEL on THURSDAY, MARCH 29th, 1923.

Mr. A. S. Stenhouse in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed: —

The Development and Nutrition of Yeast. Part II.

By Adam Tait, A.I.C., and Louis Fletcher, A.I.C.

In a previous communication (this Journ., 1922, 28, 597) on this subject we laid great stress on the importance of working under properly defined conditions and also the undesirability of generalising from particular conditions of experiment. As we did not wish to overcrowd the paper, much of the obviously necessary preliminary work requisite for the selection of the conditions adopted was omitted. As, however, these conditions and our work have been criticised adversely by A. Visez {Petit Journ. du Brasseur, 1922, 30,1107) and others it seems advisable to record some of the preliminary work which justified the selection of our conditions of working and use of the artificial nutrient solution employed in various experiments. We have been unable to obtain access to A. Visez’s original paper, which we only know of in the abstract form (this Journ., 1923, 25). As it is not probable that the abstract contains statements which do not occur in the original, we are forced to conclude that M. Visez has been in a like unfortunate position with regard to our paper and has not read the original in which the scope and limitations of our work were fully explained. In regard to other criticisms, more particularly with reference to the selection of malt rootlet extract as a source of nitrogen, we clearly pointed out our agreement with the axiomatic statement that malt wort is the best medium for growing yeast and studying its behaviour during reproduction and primary fermentation in so far as they relate to brewing. Unfortunately, however desirable this maybe, it is not a simple matter to arrange in investigations on the nitrogenous nutrition of yeast when nitrogen is the variable. We are aware, of course, that the nitrogenous constituents of malt rootlet extract are not identical with those in malt wort, but before adopting rootlet extract as the source of our variable nitrogen supply, we satisfied ourselves by direct comparison, within the limits of the question at issue, that the differences are not such as to invalidate our results. Indeed, we found that practically speaking there was no difference in their relative values as yeast foods, about 50 per cent, of the total nitrogen was readily assimilable by yeast in each case, and the final yeast crops were practically identical when the nitrogen concentration of the nutrient solution was similar to that of the malt wort.

The question of the carbohydrate composition was also considered, it being necessary to establish that the various sugars had no effect in producing differences in the yeast crops. The sugars tested were maltose, sucrose, dextrose and invert sugar. The invert sugar was made by the acid inversion of cane sugar, the acid afterwards being removed with calcium carbonate and care taken that the hydrogen ion concentration was suitable for yeast growth. It was found that the yeast crops and nitrogen assimilated were the same in each case.

Another even more important condition is the one of aeration, and as it appears to be thought in some quarters that our fermentation work was done without due attention being given to the oxygen requirements of the yeast cell, we make no apology for giving a few results which partly duplicate some of those already published, but which are more complete in regard to aeration and confirmatory of our previous statement on aeration. This did not receive particular emphasis in our previous communication simply because we were not prepared to discuss it experimentally, beyond the fact that we knew our media were sufficiently aerated, and not because it had been overlooked or that we were unaware of its importance.

In our experimental work the fermentation flasks are always shaken two or three times a day—a very important factor in keeping the fer mentation on a normal course, and, as explained later, a means of dispelling CO2 and preventing supersaturation of fermenting solutions or worts with this by-product. In Table I we give results of a set of experiments arranged on similar lines to those given in Tables II and IV of our previous work (loc. cit.). Set A was carried out under our normal conditions and Set B had a continuous stream of air bubbled through each flask. As a precaution against loss of alcohol the latter set of flasks was fitted with small condensers. The yeast used was a pure culture of S. cerevisiae but a different type from that employed in our previous experiment. It is much lighter than the former yeast, as will be seen if reference be made to the columns giving the dry weight per million cells.

Under these conditions of experiment continuous aeration has had no effect in increasing the development of yeast so far as final crops are concerned; in fact, the two sets arc practically identical. Results of other experiments on the subject of aeration are given more fully in a later part of this communication. Exception might be taken to experiment No. 5, where in Set A the numbers are not so great as in Set B. This may be, and probably is, due to an error of experiment because we have not observed anything in our other work to confirm it as being a difference due to aeration.

Up to this point practically all the data recorded have applied to the final yeast crop, both by weight and numbers, after about a week’s fermentation, by which time in most cases fermentation had come to an end. While the figures for the final crop are interesting and instructive, and under certain conditions answer their purpose quite satisfactorily, the information to be derived from a complete study of the rale of multiplication is greater and well worth the extra work involved. In the present communication we are primarily concerned with this rate of multiplication and certain of the many factors which influence it, the changes which are produced in it and the causes underlying these changes. Of the many methods employed for estimating the number of yeast cells in suspension, there is no doubt the use of the hemacytometer is the most satisfactory. Several authors have published accounts of various methods, e.g., centrifuging into narrow tubes, weighing, nitrogen-coefficients, &c.—but it cannot be gainsaid that counting the actual cells, at the very least, appeals most to one’s sense of satisfaction. There are admittedly vulnerable points in the direct counting method, but we consider these can be minimised by a little care and experience. It is mainly a question of technique, and we are of opinion that an outside estimate of the experimental error involved in the use of the hemacytometer is about 2 per cent., a figure which is in close agreement with that found by R. Pedersen (Carlsberg Repts., 1878), who was, we think, the first investigator to use it in this connection.

The study of the rate of yeast reproduction is thus by no means a new one; various workers have investigated it at different times and under a variety of conditions. Perhaps those who have done most work on this line of research are R. Pedersen, A. J. Brown, H. T. Brown, A. Slator and F. Hayduck.

In all work on yeast development and nutrition the two main considerations are the yeast itself and the medium in which it grows. In our previous communication we laid great stress on the importance of nitrogen in relation to yeast crops and before leaving this factor wish to consider other aspects, viz: —How does the nitrogen content of (1) the yeast and (2) the culture medium influence the rate of yeast multiplication? Experiments were initiated to attempt to answer these questions. Yeasts of varying nitrogen content were prepared by seeding a vigorous culture of S. cerevisiae into the invert nutrient solutions of 1040° S.G. containing varying amounts of rootlet extract as described in our previous communication (loc. cit.). In this way yeasts of nitrogen content varying from about 3 per cent, to 9 per cent, were produced. These yeasts were seeded at the rate of about 0·1 cell per unit volume (1 / 4000 mm3) into hopped wort, which had been aerated as usual for 48 hours. Portions were withdrawn at intervals after thoroughly mixing, made to a suitable volume and counts determined. The results are recorded in Table II. The fermentations were maintained at 65° F. throughout.

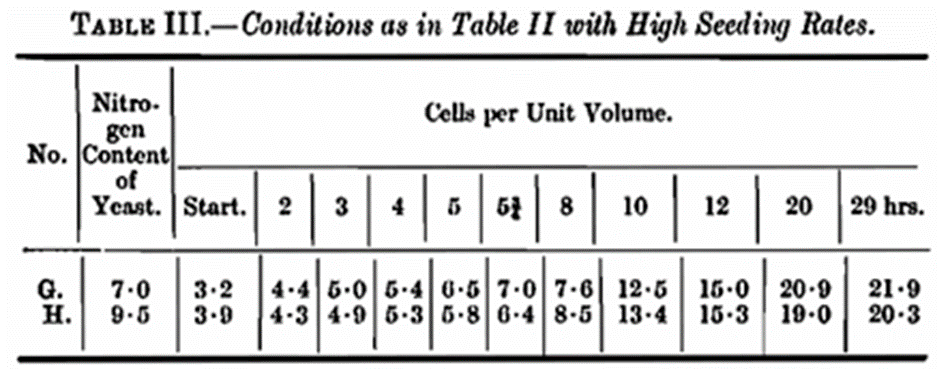

Fermentations were made, pitching the same wort as that used in the previous experiment with yeasts similar to D and F, the seeding rates however being more like those used under practical conditions, to see if there was any difference in the rate of multiplication. These two fermentations were examined at frequent intervals up to 29 hours. As will be seen from Table III it is necessary to count the cells frequently in the early stages when such seeding rates are used. The wort used in the experiments in Tables II and III was of low nitrogen content. This was arranged by dilution with carbohydrate, the object being to obtain crops with a nitrogen content about the mean of that of the seed yeasts. There are obvious extensions of the experimental conditions but so far, we have been unable to carry them out.

We have already pointed out there is a distinct relationship between the initial nitrogen content of nutrient solutions and the amount of yeast produced when these remarks applied to the final yeast crops after several days’ fermentation. We will now take up the second question to see if the nitrogen content of the medium has any influence on the rate of yeast reproduction. A fresh culture of S. cerevisiae was seeded into invert nutrient solutions of about 1040° S.G. with varying amounts of nitrogen in the form of rootlet extract after the usual aeration for 48 hours. In this particular set of experiments the seeding rate was very low—0·00022 cells per unit volume. The temperature was maintained at 65° F. throughout and counts were made at intervals up to 85 hours. The results are set out in Table IV and show that variations of the nitrogen content of the media within the limits mentioned have no influence on the rate of multiplication, though the final numbers differ.

A further set of experiments was carried out on similar lines to the above with a seeding rate of about 1 cell per unit volume. The opportunity was taken at this stage of our investigation to make a direct comparison of the rate of yeast multiplication in our artificial nutrient medium with that in malt wort, and at the same time to determine the influence of continuous aeration by bubbling a current of air through flask No. 5 for the duration of the fermentation. As a precaution against loss of alcohol in this last fermentation a small condenser was fitted to the flask. Counts were made every 3 hours up to 39 hours, by which time yeast growth had reached finality. The results are given in Table V, and it will be observed that again, when the higher rate of seeding is employed, no difference in the rate of multiplication is evident. Further, it is shown that yeast multiplication follows exactly the same course in malt wort as in the invert nutrient solution and that additional aeration has no accelerating effect, which is confirmatory of previous statements.

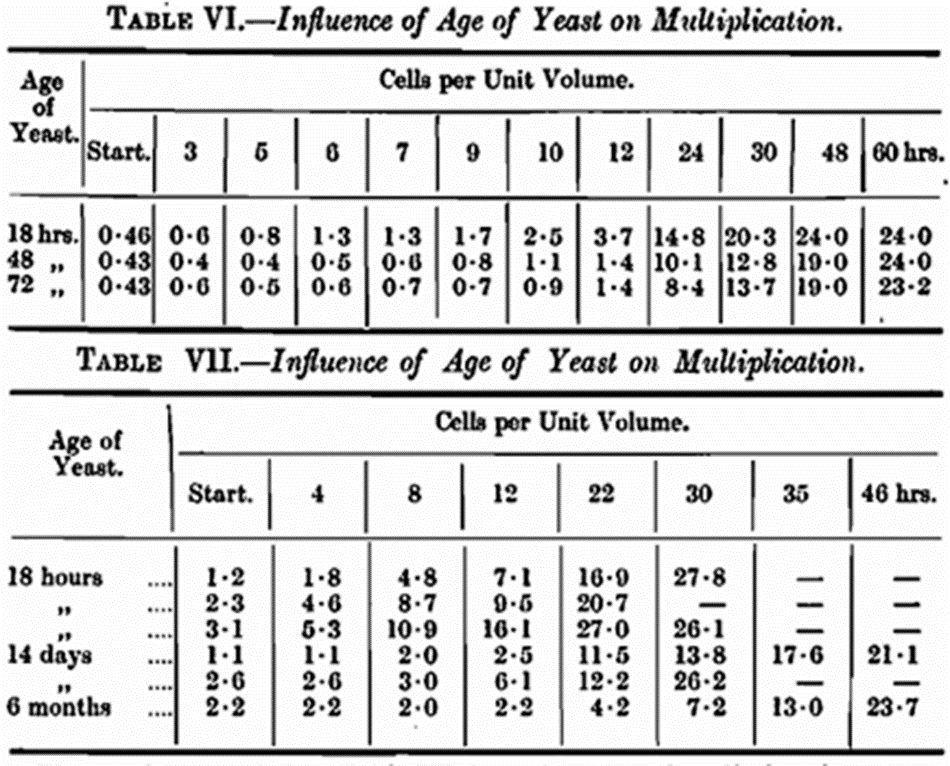

In investigations on the rate of reproduction and growth of yeast generally, it is important that the seed yeast should not be old. Throughout our work we have used 18-hour cultures except where specially stated. This is an essential precaution as will become evident later. In the experiment recorded in Table II this precaution was obviously impracticable as it took about a week to produce the different yeasts employed. On examining the rate of reproduction in the early stages of growth in this particular experiment where yeasts of different nitrogen content were used the rate of multiplication was not the same. The time required to produce a generation was much greater than usual, and there was an apparent departure from the exponential law of increase which we have found in other work with active cultures of yeast at this temperature 65° F. There was, in fact, a distinct lag phase, and the question naturally arises as to the cause of this phenomenon. Slator has already pointed out the existence of a lag-phase in yeast growth (Biochem. Journ., 1918, 12, 248). It would seem that there was some condition brought about by the age of the yeast that was responsible for the slow rate of reproduction in the early stages of growth. To test this assumption pure cultures of S. cerevisiae of varying ages were seeded into hopped wort of 1040° S.G. Counts were made at intervals and the rate of reproduction followed. The results of two sets of experiments are given in Tables VI and VII.

The results recorded in Table VI show that there is a distinct lag-phase in the 72-hour culture, less marked in the 48-hour culture and in the case of the young active culture there is practically no lag-phase with the pabulum in question, reproduction being logarithmic from the start. In Table VII the influence of age is more strikingly marked, especially in the old culture. These experiments clearly demonstrate that the use of active seed yeast is imperative and unless this precaution is taken when the rate of reproduction is being investigated, especially in the early stages, misleading conclusions are inevitable. Of course, given time the final numbers produced will tend to a constant maximum largely dependent on the pabulum. This is shown clearly in Table VI. After 60 hours the final number of cells in all three cases is practically identical, yet when the rate of reproduction is plotted very different curves result. Age of yeast alone, therefore, is sufficient to cause a distinct lag-phase in the rate of reproduction. The changes which have taken place in the yeast and other conditions which may influence the lag-phase remain for future investigation. On referring to Table II, where yeasts of different nitrogen content were used the rate of multi plication was not the same, the lag-phase being most pronounced in the case of F. This does not necessarily mean that the lag-phase increases with the nitrogenous content of the yeast. In the particular case just referred to the peculiar conditions of experiment may be responsible for a combination of circumstances promoting a lag in growth. The yeast was old, which in itself is sufficient to cause a slow start in reproduction. It was high in nitrogen content, 9·32 per cent., and seeded into a wort abnormal in nitrogen to the pabulum in which it was produced. In view of what is already known it seems feasible to assume that the lag-phase of this yeast could have been overcome by inoculating it into a wort of the same nitrogen content as its parent pabulum. The same may apply to other yeasts when the lag-phase is not due to age. Although it is always difficult to apply pure chemistry to biological processes it is reasonable to think that the reactions taking place inside a yeast cell can be compared in part to chemical inter changes. At any rate it is difficult to conceive a living entity like a yeast cell effecting a complete reversal of its functions without a pause, because the internal mechanism of the cell must be functioning in a different manner when at a stage of rest storing up reserve to that when in an active state of reproduction. Multiplication and fermentation which are proceeding simultaneously bring into operation two distinct functions of the cells.

Although we did not determine the rate of fermentation at the same time as the rate of reproduction in the experiment detailed in Table II, it seems reasonable to assume that there will be some relationship between the two. Apparent contradictions to this view may at times be observed in brewery practice. Here, in general, definite time limits are fixed for the attainment of a certain degree of fermentation. Failure to attain this with the customary pitching rate may occur, in which case the practical remedy is to increase the amount of pitching yeast. Investigation under such circumstances fails to provide an explanation as it may be found that the fermentative power of the yeast and the composition of the wort is normal. There must be, therefore, some condition of the yeast responsible for this lag in growth and fermentation; elucidation can only be obtained by a further knowledge of the subject.

In fermentations carried out under normal conditions of pabulum and age of seed yeast, the rate of cell increase follows the compound interest law, where, if N be the number of cells seeded, then in time t the increase n = N (eKt—1), when K equals the constant of growth. This has been shown by Slator (Biochem. Journ., 1913, 7, 197) to hold true for the early stages of growth. Our results are entirely in agreement with this as can be seen for example in an experiment recorded in Table VIII, where hopped wort of 1040° S.G., which had been aerated as usual for 48 hours, was seeded with a pure culture of S. cerevisiae at different rates. The fermentations were carried out at 65° F., and counts made as usual at frequent intervals.

From the results of the above experiment there is no doubt that the exponential law of increase holds good in the early stages of growth in all cases with the seeding rates employed. This is shown clearly in Fig. 1. We refer to higher seeding rates when the results in Table XII are being discussed.

The aeration of wort or other pabulum which is to be used for the growth of yeast either in the brewery for the production of beer or in small scale laboratory fermentations is of well-known importance, and in a general way has received its due measure of attention since the days of Pasteur. A. J. Brown made a special study of the influence of oxygen, followed in later years by H. T. Brown, who repeated and extended some of the former’s experiments. In fact, the study of the oxygen requirements of the yeast cell received much attention from H. T. Brown – who is undeniably responsible for the prevalent ideas regarding the relationship between oxygen and yeast growth, and whose theories on the subject have been accepted generally as correct. More recent results, however, throw doubt on Brown’s theories regarding the part played by oxygen in the metabolism of growing yeast. Notably Slator (Journ. Chem. Soc., 1921,119,115) has called attention to a few instances where actual observed facts are not in agreement with Brown’s views. It must further be admitted that Brown’s publications while they contain evidence of extensive work are somewhat lacking in a sufficiency of experimental data to enable comparisons to be made between his results and those of other experimenters. We refer especially to the paper published in the “Annals of Botany” (1914, 28, 197), which is his major contribution to the oxygen question.

We have shown that under our normal conditions of aeration the worts or artificial nutrient solutions we used in our experiments contain enough oxygen for the proper reproduction of yeast. It has been pointed out the yeast will continue to multiply according to the com pound interest law, and the generation time (G.T.) will remain a constant during the unrestricted period of growth. After this the G.T. increases owing to the restricting influence of by-products. H. T. Brown (loc. cit.) states that it is the initial oxygen charge that controls yeast growth, and that the parent cells absorb the supplies of oxygen from the medium, and that this absorbed oxygen is the “primum movens” of yeast reproduction. It is true that very little yeast growth takes place in absence of oxygen and up to a limit reproduction is proportional to the amount of oxygen in the pabulum. The same is equally true with regard to nitrogen, with the distinction that the nitrogen is present in organic combination, at least in the usual culture media and brewery worts, whereas oxygen is in the elementary state.

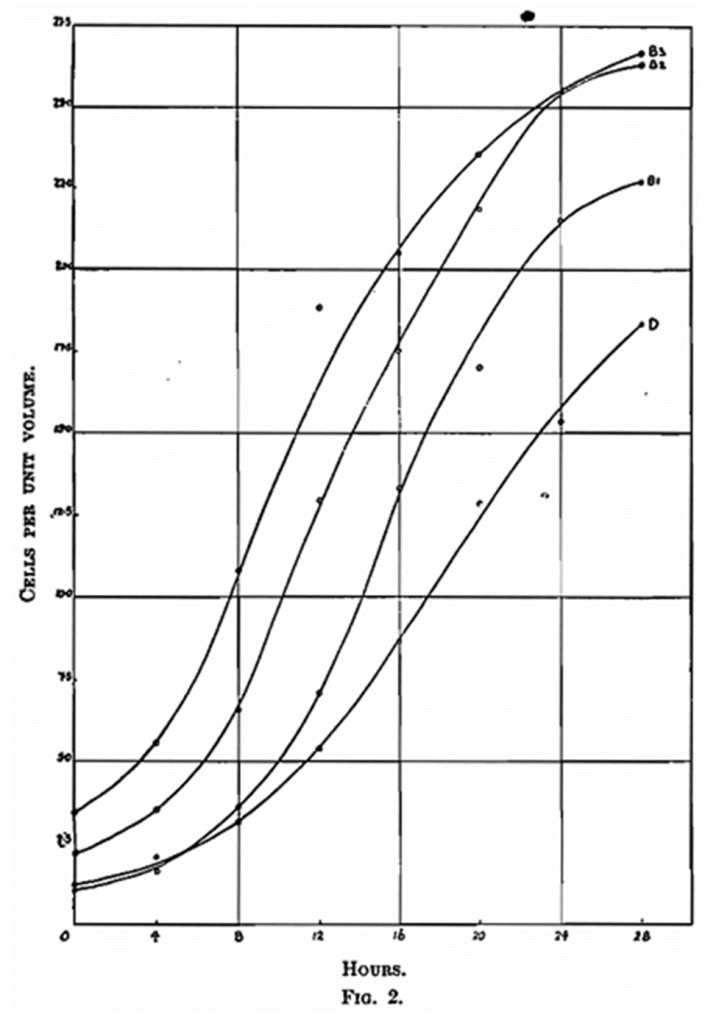

We do not consider that H. T. Brown’s conclusions, attractive though they may be, are established by his published experimental work. One point in particular which seems to us to be of paramount importance is that in a number of experiments he displaced the air above the solutions with the so-called inert gas carbonic acid. We do not think that such a procedure was justifiable as carbonic acid being a by-product of fermentation cannot be termed inert in this particular connection. Slator (Biochem. Journ., 1913, 7, 201) had already indicated that carbonic acid inhibits the rate of yeast growth and results which we record later fully confirm this view. We must admit, of course, that oxygen is the primum movens of yeast development as it is of most life as we know it. Although our work up to the present had given no indication for the assumption that the oxygen content of the parent cells was the deciding factor in their ultimate development, we thought it would at least be interesting to see if in any way this initial oxygen charge could be increased and thereby bring about an enhanced reproductive capacity in the parent cells. We prepared a quantity of pure active S. cerevisiae, and seeded it at the rate of one, two and three cells per unit volume into (A) wort through which air had been bubbled 15 minutes and (B) wort through which pure oxygen had been bubbled for the same period. By this means the volume of oxygen at the disposal of the parent cells in B was five times that in the case of A. After seeding, the flasks were allowed to stand for 4 hours at 65° F. during which time the air was bubbled through set A and oxygen through set B. Four hours was selected as being ample time for the yeast to fix its requisite amount of oxygen. We were guided in the selection of this length of time by the work of H. T. Brown. After the “fixation” period each flask was connected to a cylinder of pure nitrogen, and the supernatant atmosphere replaced by passing nitrogen over the surface of the solutions for 5 – 10 minutes. The flasks were plugged and fermentation allowed to proceed at 65° F. When sampling, the flasks were connected to the nitrogen cylinder and a slow current of this gas passed over the surface of the solutions during operations. Since the flasks were sampled every 4 hours and also received extra shaking between sampling, supersaturation of carbonic acid was reduced to a minimum. The results are given in Table IX and Set B expressed graphically in Fig. 2.

Contemporaneously with the above experiment two other flasks of 100 c.c. malt wort aerated in our usual manner were seeded with the same yeast as used above at the rate of about one cell per unit volume. The flasks were then allowed to stand for 4 hours for the “fixation” of oxygen by the yeast. Flask C was connected to the nitrogen cylinder and D to the carbonic acid cylinder. In these cases, the gases were allowed to bubble through the respective worts as well as over the surface, the latter stream being employed to keep down frothing. As a precaution against the possible loss of alcohol during fermentation the flasks were fitted with small condensers. Counts were made at intervals of 4 hours as before; similar precautions being taken during the operation of sampling. Comparing Al and Bl in Table X with experiment C, which is the nitrogen flask, it will be seen that all three are practically identical throughout. In experiment D the effect of carbonic acid perse is very striking, but at the same time it must be pointed out that its influence is merely one of increasing the generation time and not of altering the mode of growth—an important observation.

The carbonic acid figures in Table X are shown as curve D in Fig. 2, alongside those of set B from Table IX. The figures in experiment C, Table X, are the same as those of Al and Bl, Table IX, and therefore the curve shown as Bl, in Fig. 2, will serve for Al, Table IX, and C, Table X, thus affording a direct comparison between the influence of oxygen or air, nitrogen and carbonic acid.

Nitrogen was selected as being the only permissible inert gas which could be used in connection with reproductive work. Obviously carbonic acid is impracticable since it would be functioning in a double role. As regards hydrogen, which has been extensively employed by other workers as an inert gas we are not prepared to admit that it can be considered as such. Reverting again to A1 and B1 in Table IX, and C in Table X, we have observed that the three experiments are practically identical, which in itself is satisfactory proof of the value of nitrogen for this particular purpose. Another striking example of this fact is revealed in Table XII. (High seeding rate experiment.)

Under our normal conditions of aeration when wort is seeded with an active culture of pure yeast at the rate of 0·01 cell per unit volume and allowed to stand at 65° F. without disturbance in any way the yeast produced at the end of 47 hours is 6·6 cells per unit volume. This corresponds to the formation of 9-37generations with a G.T. of 5·0 hours. On the other hand a similar fermentation starting with 0-008 cell per unit volume, but which was shaken vigorously at frequent intervals, produced at the end of 48 hours 19·5 cells per unit volume, corresponding to 11·2 generations or a G.T. of 4·3 hours.

We will next consider fermentations under similar conditions with regard to flask, wort, temperature, etc., the only difference being that the atmosphere in the flasks above the liquid was replaced by carbonic acid immediately after seeding. Starting with 0·012 cell per unit volume at the end of 53 hours 5·8 cells per unit volume were produced corresponding to 8·9 generations or a G.T. of 5·9 hours when the flask was left undisturbed during fermentation. When, however, the flask was agitated at frequent intervals during a period of 48 hours with a seeding rate of 0·008 cell per unit volume the yeast produced was 15·0 cells per unit volume, equal to 10·9 generations or a G.T. of 4·4 hours.

Summarising, we get the figures set out below in Table XI.

Before discussing the figures recorded in the above table, it must be pointed out that we know that in these experiments, reproduction at the time of counting was following the exponential law of increase. This is a point to be noted, because had fermentation been allowed to proceed for, say, double the length of time the final yeast crops would most probably have reached the same figure, giving the same value for the G.T.

At first sight it would appear that agitation is the governing factor in these experiments. However, a more valid inference, and one which is supported by other observations and experiments, is that carbonic acid per se has a pronounced inhibitory effect on the rate of reproduction. Considering yeast growth on general biological grounds it is only to be expected that the by-products will act as inhibitants. Carbon dioxide is practically equal with alcohol in being the most abundant by-product of the action of yeast on sugar during an ordinary fermentation, and naturally it may be inferred that its. presence in solution will have an inhibitory effect. We do not deny that agitation in itself may under certain conditions have a decided influence in promoting yeast growth, most probably by assisting diffusion. Its more direct action, however, is the removal of and the prevention of supersaturation by carbonic acid. Fermentations proceeding without agitation are capable of retaining in solution a much larger volume of carbonic acid than is demanded by the saturation coefficient in wort or beer. In fact, we have found by direct experiment that this supersaturation can be anything up to 25 per cent, increase over the ordinary solubility figure.

The influence of carbonic acid and the importance of preventing supersaturation was not fully realised in our earlier work. This does not vitiate the results of some of our earlier experiments on final crop as these were purely relative under the specified conditions. It however accounts for certain apparent disagreements between different sets of experiments.

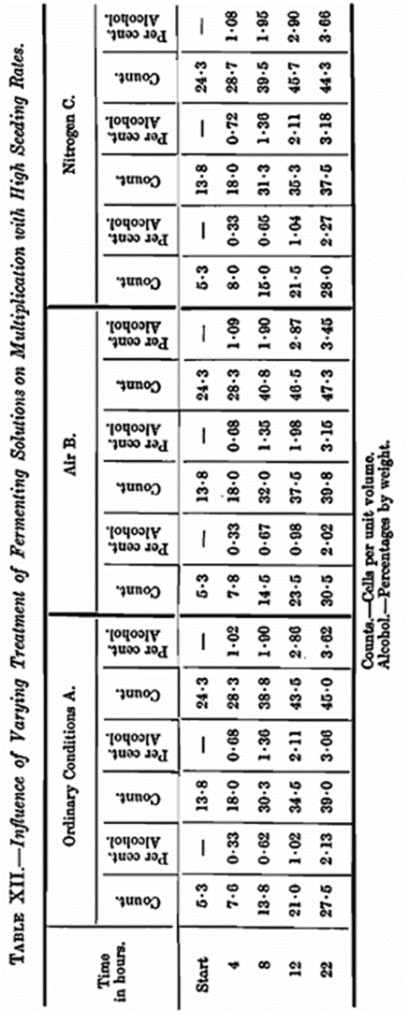

In the foregoing experiments on the influence of aeration the maximum seeding rate was one cell per unit volume. It seemed desirable to supplement these observations with much higher seeding rates and an experiment was arranged seeding with about 5, 15 and 25 cells per unit volume which roughly corresponds to 0·5, 1·5 and 2·5 grams pressed yeast per 100 c.c. In addition to making counts of the cells the alcohol produced was determined at the same time intervals. As in these experiments it was obviously important to eliminate the lag-phase, a large quantity of yeast about 18 hours old was prepared. It was necessary to obtain about 200 grams of pure culture yeast and it is easy to realise that the production of this amount is not a simple matter under ordinary laboratory conditions. By using a sufficiency of primary seed cultures, we endeavoured to overcome the difficulty. The results recorded show that we failed to do so completely; this however docs not destroy the value of the experiment. The yeast was seeded in the numbers already mentioned into wide necked bottles of two litres capacity. Those used in set B and set C were fitted with small condensers and two inlet tubes with restricted nozzles. The one tube was carried to the bottom of the bottle and the other placed at such a height as to enable a current of the particular gas employed to be blown on to the surface of the fermenting wort, the object of the latter arrangement being to destroy frothing. Loss of alcohol was prevented by the use of the condensers. Three sets of three bottles were prepared each containing one litre of wort and seeded at the rates already mentioned. Set A was approximately under our normal conditions, i.e., bottle neck plugged with cotton wool. It was necessary in this set to shake the bottles every 15 minutes to prevent frothing of these very energetic fermentations. Set A was therefore under de-supersaturated conditions. Set B was subjected to continuous aeration both through the liquid and on the surface, as already explained, thus ensuring complete aeration, decarbonation and agitation. The contents of the third set of bottles, set C, were agitated in a similar manner to the last set with a current of pure nitrogen. This set was therefore decarbonated and agitated. Portions of about 125 c.c. were withdrawn, after thorough mixing, at the intervals stated. Further action was stopped in these portions by the addition of a measured quantity of 20 per cent, sulphuric acid sufficient for the purpose. Counts of the yeast and estimation of alcohol were made, the necessary corrections for dilutions, yeast cell displacements, etc., being made in the various calculations.

Although the difficulties of carrying out this experiment were formidable, we consider the results are sufficiently accurate to justify the conclusion that additional aeration has no effect in augmenting the rate of growth, the amount of yeast produced, or of increasing the rate of fermentation even when such high seeding rates are employed. The results are set out in detail in Table XII.

H. T. Brown (loc. cit.) has stated that with a low seeding rate, say 0·1 cell per unit volume the rate of reproduction is slowed down very considerably owing to the slower absorption of the available oxygen by the yeast. This absorption he states is very rapid with a “density of population” of yeast cells equivalent to 1 or more per unit volume, but with anything less than this the rate of absorption is so slow that sufficient time elapses to allow more or less complete diffusion of the dissolved oxygen into the inert gas, carbonic acid, which he uses to replace the air above the solution to be fermented. Why this is so is not easy to comprehend. If there is a difference in the rate of absorption of oxygen one would expect to find it in the opposite direction. By decreasing the seeding rate there will be less overcrowding and less competition for the dissolved oxygen so that the rate of oxygen absorption should increase, or at any rate it ought not to be slower. As a matter of fact, a careful study of the curves published by Brown (loc. cit.) show that it is not the rate but the total amount of oxygen absorbed that is proportional to the number of yeast cells present during the “fixation” period—two totally different things.

In order to obtain more exhaustive information regarding the rate of reproduction of yeast and the concurrent changes in the pabulum an experiment was arranged as follows: —Three 3-litre portions of hopped malt wort of S.G. 1045°, contained in 5·5 litre flasks, aerated as usual by standing for 48 hours, were seeded with an active pure culture of S. cerevisiae at the rate of (A) 0·11, (B) 1·0 and (C) 2·7 cells per unit volume. At frequent intervals during fermentation portions of about 125 c.c. were removed after thoroughly mixing the contents of the flasks, and the following determinations made, viz.: — Weight of pressed yeast, number of cells, nitrogen, phosphoric acid, alcohol and indirectly amount of sugar fermented. The results are set out in Table XIII and certain of the figures arc shown graphically in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

At the termination of these fermentations, which were evidently complete before 72 hours, the results are practically the same in all cases. This alone is another striking example of what was said earlier in the paper about drawing conclusions from final results without taking into consideration the question of velocity, as it can be seen that the major part of the fermentation, etc., is over at varying times depending on the seeding rate. Taking the question of rate of yeast development, first it will be noticed that this went on without restriction up to a point where the numbers were about 12 cells per unit volume. Up to this stage the G.T. had been fairly constant and in close agreement with our other experimental work. On looking at the time when this amount of yeast had been produced, we find that the alcoholic content is about 0·7 per cent, in all three cases. This corresponds to the fermentation of about 1·4 gm. of sugar per 100 c.c, and as there is a matter of 8 or 9 gm. of readily fermentable sugar in the wort used in the experiment, it cannot be a lack of carbohydrate which is responsible for the decreasing velocity of yeast reproduction. A glance at the nitrogen and phosphoric acid figures shows that there is no shortage of these constituents at this stage of the fermentation. We are therefore forced to conclude that a concentration of 0·7 per cent, alcohol with the amount of carbonic acid retained in solution retards the rate of growth with the seeding rates in question. With high seeding rates this is not so marked as shown in Table XII where the seeding rates varied from about 5 to 25 cells per unit volume. Presumably in these instances the ratio of mass of yeast to by-products plays a part. There is little doubt that from the start of fermentation the by-products retard the rate of repro duction, but obviously the influence in the very early stages is so slight that ordinary methods fail to detect it.

When the time intervals are arranged as in Table XIII mathematical investigation of the results shows that retardation is actually noticeable in the very early stages and that K, the constant of growth, decreases rapidly. The figure we give for this alcohol content is much lower than that generally accepted as being necessary to show any effect on the rate of yeast reproduction. In addition to the retardation brought about by the alcohol there is, as mentioned previously, further retardation due to the dissolved carbonic acid produced simultaneously with the alcohol. From the data given in Table XIII it is possible to calculate with a fair degree of accuracy the amount of alcohol which will be produced in a given time by a known weight of yeast. Working under our normal conditions at 65° F. we find that 0·12 gm. alcohol is produced per hour by one gram of pressed yeast, a useful but only an approximate mean value. In Table XII, leaving out of consideration the obvious lag phase, it will be seen that after 8 hours, with the lowest seeding rate, i.e., 5·3 cells per unit volume, the rate of increase falls off and here we have nearly attained our 0·7 per cent, alcohol limit. With the higher seeding rates in one case the limit has been approached and in the other exceeded, but notwithstanding this we have in the next time interval a greater increase in the number of cells than is in consonance with our general statement as regards the retarding influence of alcohol and carbonic acid. This, as suggested before, may be explained by the ratio of yeast to by-products. These observations are not without interest to certain branches of the fermentation industries other than brewing.

Perusal of the results in Table XIII shows that in the very early stages of fermentation the amounts of alcohol formed, and thus sugars fermented, practically follow the same exponential law as the increase of cells. This is in accordance with Slator (Biochem. Journ., 1913, 7, 197), who pointed out that under certain prescribed conditions the time fermentation curve is logarithmic and that the constant of this curve is the constant of growth. Under the conditions fixed by Slator this is no doubt so nearly true that for purposes of calculation it may be assumed to be exact. Apart from this point of view, as the conditions laid down by Slator apply only to the first 2 per cent, of the fermentation, it is of some interest to extend our consideration of the changes taking place. Inspection of Table XIII (set B), in the more advanced stages, shows that the alcohol formed and the rate of yeast reproduction do not follow the same exponential law. During the stage when reproduction is still active it may be that the young daughter cells do not produce so much alcohol per unit of time as mature cells. It seems quite reasonable to assume that a certain time must elapse before the daughter cells attain their full enzymatic activity. When reproduction has slackened so much as virtually to cease, in this case at about a limit of 2 per cent, alcohol, fermentation continues as a linear function of the time for a period, until accumulation of alcohol and diminution of sugar concentration brings the reaction to an end. As regards the values for assimilation of nitrogen and phosphoric acid it will be noticed that up to the production of 2 per cent, alcohol, these follow an approximately similar exponential law; beyond that limit when reproduction ceases, assimilation of nitrogen and phosphoric acid likewise cease. In the case of the increase of weight of cells this follows much the same exponential law up to our limit, thereafter there is a very marked increase in the weight of the individual cells followed by a distinct reduction. This result throws some doubt on the value of weighing as a means of measuring reproduction or yeast crops, and indicates that certain precautions must be taken when this method is used. A diagrammatic representation of the course of fermentation under the above conditions is given in Fig. 7.

Summary.

Although we cannot claim to have established any very new or original conceptions in regard to the development and nutrition of yeast, our results throw light on much which up to the present has been more or less obscure and explain more fully the influence of certain factors on yeast growth. The chief points may be summarised as follows: —

(1) There is practically no difference in the relative values of the nitrogenous constituents of malt rootlets and malt worts as yeast food.

(2) Worts or artificial nutrient solutions when aerated by standing for 48 hours at room temperature contain sufficient oxygen for the normal reproduction of yeast.

(3) The age of the seeding yeast is one of the main factors in bringing about a lag phase in the early stages of growth, and when the rate of multiplication is being investigated precautions should be taken to obviate this lag phase by seeding with active cultures.

(4) Continuous aeration does not influence the rate of reproduction under the conditions laid down in this contribution.

(5) Carbon dioxide should not be used as a means of displacing the air above fermenting solutions as this gas has a distinct retarding influence on the rate of yeast multiplication.

(6) In fermentations carried out under normal conditions as regards seeding rates, pabulum and age of seed yeast, the rate of cell increase follows the compound interest law, where if N be the number of cells seeded then in time t the increase n = N (e Kt — 1) where K equals the constant of growth. There is little doubt that the compound interest law holds good until multiplication ceases, but as food supplies diminish and by products increase K decreases rapidly until it becomes infinitely small. In the course of our experimental work, we have failed to find the slightest evidence that, during active reproduction, the rate of yeast development is a linear function of the time as stated by H. T. Brown.

(7) At a concentration of about 0·7 per cent, alcohol with the carbonic acid retained in solution there is a marked retardation in the rate of yeast reproduction. This concentration of alcohol is much less than that generally accepted as being necessary to bring about retardation. This statement applies to conditions of seeding, etc., which permit of the formation of several generations.

(8) Generally speaking, under our conditions of experiment, except in the very early stages, the alcohol formed and the rate of yeast multiplication do not follow the same exponential law.

(9) Owing to the variation in weight of cells during fermentation general conclusions cannot be deduced from the weights of final crops. Preferable methods are the determination of the nitrogen coefficient devised and used by H. T. Brown, or direct counting, which is more reliable.

In conclusion, it is our pleasant duty to express our appreciation of the valuable assistance we have had from Mr. J. S. Ford. The whole of our work is the direct outcome of his teaching and we would like to state with all due deference that we consider ourselves extremely fortunate in having such a long association with him. Only those who have experienced the guidance of a master hand can appreciate its full value towards successful work. Not only in the course of the research work itself but also in elaborating the present communication, Mr. Ford has given us the full benefit of his long experience and creative ability, which, in conjunction with the time he has taken and the kindly interest shown in discussing the whole subject with us, has made the work throughout a very real pleasure. We also wish to thank one of our colleagues, Mr. J. B. Westwood, for his energetic assistance in carrying out some of the experimental work, and especially for his help in making many of the counts when it was necessary to follow the rate of yeast multiplication at regularly short intervals over a long period.

Discussion.

Dr. Clerk Ranken said that he had listened to Messrs. Tait and Fletcher’s paper with great interest, and it was interesting to note that their work confirmed Slator’s, in that the accumulation of carbonic acid during fermentation was toxic. That was, after all, what one might expect if they looked upon fermentation as a chemical action obeying the law of mass action. If two substances acted on each other producing two others, the reaction proceeded until the accumulation of the second two substances caused the rate of reaction to slow down and eventually stop, bringing about a state of equilibrium. If, however, the product, or products of the reaction, in this case the carbonic acid, was removed from the sphere of action, the reaction would proceed further until one or other of the primary substances was used up. That the fermentation follows the law of mass action was also seen by the fact that the greater seeding rate, i.e., the greater mass of yeast caused the reaction to proceed further before equilibrium was reached.

That the lag phase was longer in the case of old yeast than in young was noteworthy. The explanation might lie in the fact that, as the yeast stood, an accumulation of amino acids was produced. The old idea was that amino acids were the most suitable food for yeast, but the modern idea held that some amino acids, he would not say all, were toxic to enzymes. This has been shown to be the case by certain American workers. Might it not be that the accumulation of amino acids in the older yeasts were toxic to the enzymes of the yeast, the zymase, invertase, etc., so that when put into wort the yeast refused to show activity until the excess of amino acid had been got rid of, probably by diffusion into the wort. He would also like to ask how the phosphates were estimated, and if any precautions were taken to free the nitrogen from traces of oxygen. His experience with nitrogen was that alkaline hydro-sulphite acted most efficiently.

Mr. S. H. Hastie congratulated the authors on their paper. He wished the distillers would waken up to the scientific needs of their industry as the brewers had done. No doubt in the years to come distillers would realise that it was to their advantage to obtain all the scientific aid they could. He would like to ask the authors if the shape and form of the vessel had any effect on the quantity of alcohol produced during a fermentation, as he has reason to believe that such was the case. Doubtless the fermentation experiments described reported in the paper were made in flasks of a standard pattern.

Mr. Tait, in reply to Dr. Ranken, said that Mr. Fletcher and he quite realised the importance of the lag phase in yeast reproduction and they intended to go more fully into the subject. When they did so they would keep in mind the suggestion about the accumulation of ammo acids. Regarding the two questions asked by Dr. Ranken, the phosphoric acid was estimated by the phosphomolybdate method after incinerating the worts or “beers” with magnesia. The gaseous nitrogen used in their experiments was passed from the cylinder through pyro gallic acid to free it from any oxygen that might be present, and they were of opinion that this procedure was quite sufficient for the particular purpose for which it was used.

With regard to the points raised by Mr. Hastie, they were at one with him in so far as the distiller should abandon rule-of-thumb methods as far as possible and try to get to bedrock regarding the various processes involved in the manufacture of spirits. Except where specifically mentioned they had used 300 c.c. Erlemeyer flasks. They had tried various experiments with different shaped glass vessels, and it was found that there were great differences in the amount of yeast produced. The results show that this part of the subject is very complicated, and that various factors must be considered before any definite conclusions can be drawn.

In acknowledging the vote of thanks proposed by the chairman, Mr. Tait said that he appreciated very much the way the paper had been received, and only hoped that it would help to throw more light on some of the rather obscure points connected with the scientific side of brewing, and also of everyday practice.