MEETING of the LONDON SECTION held at the ENGINEERS’ CLUB, COVENTRY Street, on MONDAY, 12th APRIL, 1926.

Mr. C. A. Finzell, M.A., in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed:

THE DEVELOPMENT AND NUTRITION OF YEAST. — PART III.

THE LAG PHASE AND ASSOCIATED PHENOMENA.

By Adam Tait, F.I.C., and Louis Fletcher, A.I.C.

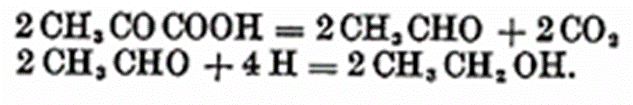

It has long been known that two of the main essential constituents of the food requirements of yeast for normal growth during fermentation are of a nitrogenous and carbohydrate nature. After these substances have been assimilated by the yeast during an exhaustive fermentation of, say, a malt wort, and the yeast crop allowed to remain in contact with the fermented wort or beer, certain changes take place in the yeast. A microscopical examination alone is sufficient to detect the difference in the appearance of the protoplasm of the cells of a fresh and of a stored yeast. It is now well known that yeast, which has been stored in beer for a long period, exhibits a lag-phase in growth when it is seeded into fresh malt wort or other nutrient media. As in the case of other organisms the main objects of yeast are the maintenance of life and the reproduction of its species it may rightly be conceded that during this storage period the cells contrive to keep alive by using up the nitrogenous and carbohydrate substances which they have accumulated as reserves. The metabolism which occurs during this resting stage (storage) is little known and difficult to follow and the main part of the present investigation is an attempt to elucidate certain of the changes which take place during this particular and important stage in the life history of yeast. Much depends on the conditions of storage, as will be shown more fully later, but in general it would seem quite reasonable to accept the common opinion that the nitrogenous changes will be on the down grade with the probable pro duction of amino bodies. With regard to the carbohydrate reserve, glycogen, Harden and Rowland (J. Chem.Soc., 1901, 25, 1227) have established that conditions do alter the course of the action in the auto-fermentation of the glycogen. The great disparity in the ages of the individual cells is a factor which must influence the later history of any particular mass of yeast. At the end of a fermentation where the pitching rate was high and the number of generations formed consequently limited to two or three, the crop will obviously contain new cells possessing a greater equality in age than those of a crop collected from the fermentation where the seed rate was very much lower. This, however, applies to the new yeast only, aa nothing can be said of the original yeast which might easily have contained cells of relatively great age. The small seeding, on the other hand, yields a crop of, say, 8 to 10 generations which permits of mathematical calculation of the average age of the whole, as in this case the number of parent cells being small can be neglected. We would emphasise due consideration of these facts as being essential for a complete conception of all statistical work, for while it is admitted that practically all work dealing with minute organisms must be statistical, and the results accruing from the study of millions give an idea concerning the average individual, this average must be influenced greatly by the facts just expressed. This must apply to yeast in any state, i.e., whether in active reproduction or during auto-fermentation in the resting state. Perhaps it is of greater importance in the particular state of immediate interest, viz., auto-fermentation. The older cells must be in a more advanced stage of internal disruption, and it may be that the products of these complicated actions have some influence on the neighbouring cells which may be younger and consequently possess greater vitality. Before going further, let us try to picture in our minds the changes likely to take place during auto-fermentation. Let us assume that yeast is allowed to stand for a day or two in its own beer after a complete fermentation, then it is well known that the original gravity of the surrounding beer increases— due mainly to alcohol produced from the auto-fermented glycogen—and for the same reason there is a loss in weight of the yeast cells. (See Hind, this Journ., 1925, 31, 336, and Harman and Oliver ibid, 353). In this connection in Table 1 (see Appendix) we give results obtained by ourselves of the analyses of pressings made after increasing periods of contact with yeast. As already mentioned, there will probably be a degradation of the nitrogenous substances of the yeast. If the stored yeast is then transferred (seeded) into some fresh wort a lag-phase in growth is observed, and the magnitude of this lag depends, inter alia, on the age of the yeast. During this lag period it is hardly likely that the yeast is lying quiescent, although so far as reproduction in terms of actual numbers is concerned this is so. A more probable state of affairs is that when old yeast is seeded into fresh wort the cells immediately set to work to repair the ravages which have taken place during storage under starvation conditions, so that in reality the lag phase might be termed a building-up process. This assumption was proved to be correct because a yeast which had been left in contact with beer for eight clays lost about 20 per cent, of its weight during that period, but when seeded into fresh wort this stored yeast gained in weight before any measurable reproduction took place and during this quiescent period there was an appreciable assimilation of nitrogen (Table II.). This confirms what we have shown before (this Journ., 1923, 29, 509) that ageing of yeast during storage alone plays an important role in the production of a lag phase, but, of course, there may be, and probably are, several other contributory causes, some of which may be linked up completely with the main cause, while others act independently. It seems reasonable to postulate that storage is accompanied by enzymic changes and therefore the rate of change will vary greatly with the temperature. Experiments in this connection are recorded in Table III. the results of which show that this is the case. These observations are not without practical importance.

When yeast is stored in water, and in water containing alcohol, it is only when the concentration reaches about four per cent, that there is any decided increase in the lag phase when the various yeasts arc seeded into fresh wort and the rate of reproduction is measured. (Table IV.). It must be remembered’ that this refers to a washed pure culture of Scotch yeast and must not be confused with the later storage experiments. The influence of alcohol on yeast during storage will be referred to more fully at a later stage.

So far, we have been unable to produce evidence for any simple explanation of the changes which take place during storage of yeast and which bring about the lag in growth at the commencement of a fermentation. The influence of temperature in increasing the lag phase points to the endo-cellular changes being of an enzymic nature, and so it was deemed advisable to ascertain if the hydrogen-ion concentration of the storage liquid had any effect in accelerating or retarding these changes. At present we are only considering the conditions of the environment of the yeast during storage; the question of the hydrogen-ion concentration of the inside of the cells will be referred to after when the storage of yeast in the pressed state is being discussed. The same culture yeast was used, it was stored in mixed phosphates of the described, hydrogen-ion concentration in the proportions of 1 gm. yeast per 100 cc. solution. Any slight plasmolysis which might occur under these conditions will affect the whole series equally and therefore not upset the relative values. The pH of the storage media before and after storage are interesting figures and show that the yeast has not remained inert during its period of incubation in the liquids. From the results of the reproduction tests there is evidence of a favourable hydrogen-ion concentration and this seems to be between pH 5·0 and 6·0. (See Table V.).

Reverting now to the statement that during storage yeast uses up its glycogen, and that the auto-fermentation of this carbohydrate accounts for the greater part of the loss of weight it was found that it was possible to restore to an old yeast its carbohydrate content and at the same time reduce the lag phase of development when seeded into a fresh nitrogenous pabulum. Brewery pressed yeast which had been further pressed between cloth in a hand-press and which had been stored in air, was put into a mineral nutrient solution of invert sugar free from nitrogen and allowed to remain for 3 days. When seeded into a suitable nitrogenous medium the yeast commenced to grow at the ordinary logarithmic rate after a lag period of about 6 hours, whereas in the case of the same yeast without the preliminary storage in the nitrogen free carbohydrate solution it was only after 24 hours that any real signs of growth took place. This experiment was repeated with the difference that the yeast was taken from the brewery in the fluid state, filtered and well washed in a Buchner funnel. It was hand-pressed as before. The general trend of the results was the same, showing that storage in a nitrogen free carbohydrate solution lessened the period of lag, but the control yeast this time did not exhibit nearly such a pronounced lag as before.

A further experiment was then carried out, using two portions of the same yeast taken from the brewery press. One portion was washed on a Buchner funnel with distilled water before being subjected to the hand-press treatment. The other portion was hand pressed without any preliminary washing. Similar results to those found above were obtained and confirmed the difference in the behaviour of washed and unwashed yeast. The number of dead cells was determined by methylene blue staining after storage and it was found that the number was six times greater in the case of the unwashed yeast. (Table VI., Fig. 1).

The fortuitous observation of this remark able difference in behaviour between washed and unwashed yeast during storage prompted us at once to ascertain if this phenomenon was common to brewery yeasts, and through the kindness of friends in different parts of the country we obtained various specimens of yeast all of which responded similarly to the washing treatment. This general result led us to make an immediate investigation as to the nature and cause of this difference, with the result that the course of the work was diverted along unpremeditated channels and became a study of the phenomena occurring in stored or resting yeast. This does not necessarily mean a divergence from the original object of the research which properly defined was an investigation into the cause of the lag phase of yeast growth and the conditions which bring about, influence and regulate this lag phase. That the lag phase of growth and the resting state of yeast arc indissolubly connected is obvious from our results and that the one must precede the other is also undisputed, so that if the previous work has been in a backward direction, we have, at any rate, now arrived at the stage when a progressive movement is indicated. As stated before, the ageing of yeast is one of the causes of the lag phase of yeast growth, and in a way that is quite true, but it would be more correct to state that ageing induces the conditions and factors which are the cause of the lag period, in the subsequent development of yeast. Storage or if preferred, the resting period, is therefore another name for ageing.

We have so far dealt with the experimental results in chronological order, and it is our purpose to continue on these lines as we consider this to be the most suitable way of describing the present research. Thus, it becomes possible to discuss results as obtained on their own merits, without confusing the issue by introducing later and probably conflicting evidence. In this way the individual steps of the investigation are brought out, and the pointers which have guided the work to its present stage are indicated.

Before proceeding further with the investigation, it became necessary to devise suitable methods for measuring the changes taking place in yeast when it is stored, as a mere estimation of the dead cells is inadequate. Owing to the very large number of determinations to be made in a relatively short time it was decided at the outset that absolute determination of any of the constituents of yeast was not essential for the purpose, but rather some reliable and easily manipulated methods which would indicate relative differences in certain components of the yeasts. One of the primary difficulties was to differentiate between what was inside and outside the cells, and though we have no wish to be drawn into a discussion on this difficult and controversial subject it is one which we could not entirely ignore. Therefore, we were compelled to make an investigation into the amount of interstitial fluid present in ordinary pressed yeast and in hand-pressed yeast employed in most of our work. We purpose publishing at some future date a note on this subject. In the meantime, we need only say that in the yeast as hand-pressed for our experiments the interstitial fluid was about 0·5 cc. per 100 gm, of yeast, a value in agreement with that given by Paine (Proc. Roy. Soc. 1911, B 84, 289-307). It is thus evident that so far as our experiments are concerned the interstitial fluid cannot play a very important part, at the same time under other conditions of working, viz., with ordinary pressed yeast its presence would have to be considered, not so much on account of water, as a mere diluent, but rather on account of the dissolved colloidal and other substances associated with it. In pressed yeast there is an enormous surface (in one gram the surface is about 1,000 sq. inches) which introduces intricate surface phenomena. Further complications arc brought about by the presence of substances on and in the cell walls and these cannot be ignored nor can they be altogether considered either as part of the external or of the internal matter, although for most purposes the latter will have the greater claim. These considerations, and in conjunction the known rapid interchange occurring between the inside and outside of the cells, show that an aqueous extract of yeast must be inadequate as a means of measuring changes inside the cell. Solid matter is certainly removed from the inside of yeast when immersed in water, but it is a relatively small amount and does not indicate the changes looked for. Boiling water as an extractive is open to objections, for the reason that such treatment affects the soluble matter and does not yield extracts of regular composition.

As a result of much preliminary work, it was decided to extract the yeast with alcohol (Sp. Gr. 0·827) using the solution so obtained for estimating the total acidity, “formol” nitrogen and “total” nitrogen. The yeast experimented on was always taken fresh from the brewery press and then pressed in cloth in a hand-press. This gave a white, “dry” crumbly yeast quite easy to manipulate. By washed yeast is meant brewery pressed yeast washed by suspending it in 10 times its weight of water, filtering through a Buchner funnel, with a slight extra wash on the filter, and then hand-pressing as before. It should be mentioned that if the yeasts are stored in the ordinary pressed state, that is without hand-pressing, results of a similar nature are obtained. The conditions of storage and the methods of analysis are given in detail in the appendix.

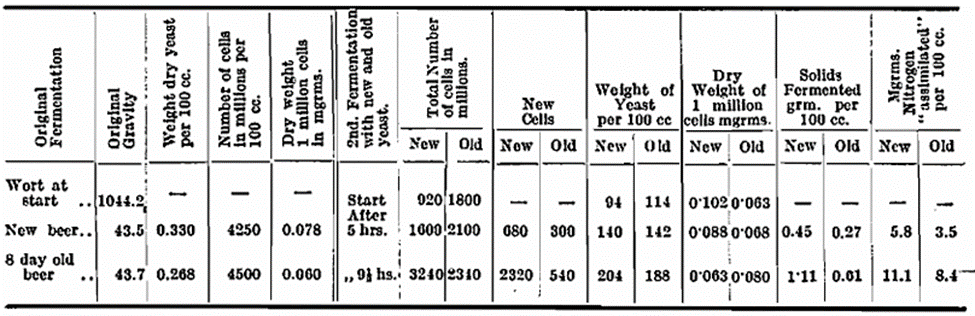

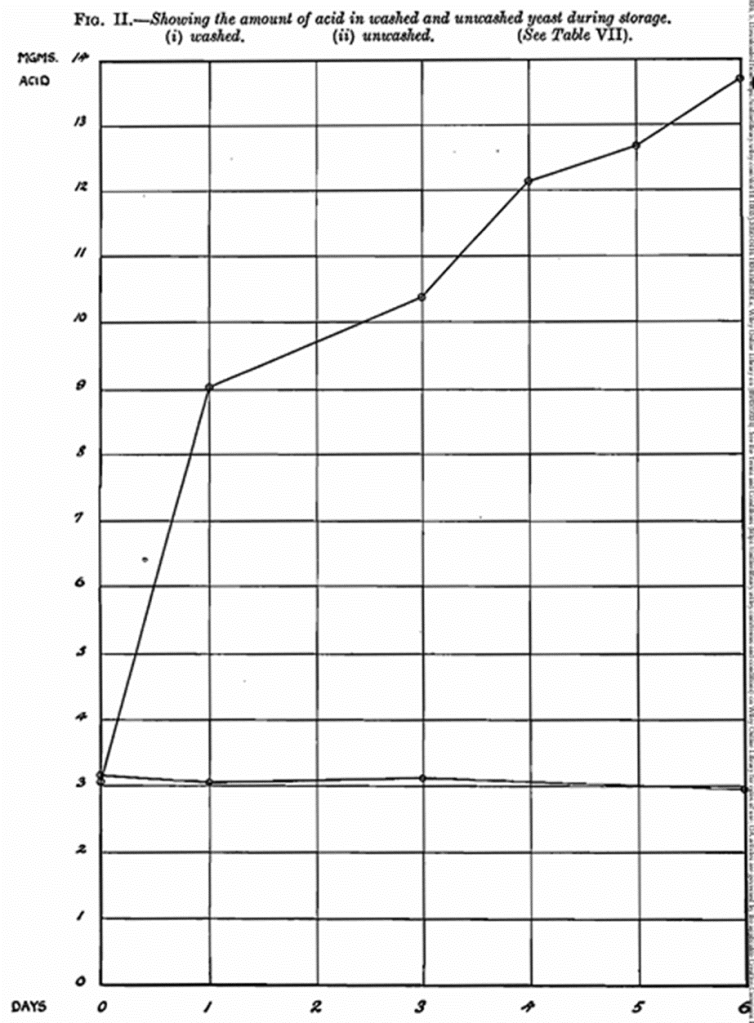

In the preliminary experiments with these methods the difference in the behaviour of unwashed and washed brewery yeast stored in air was first of all determined. This was followed up by observing the differences occurring when air was replaced by other, gases, such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen. The results derived from these preliminaries were of so interesting a character that the whole was repeated, this time on the same batch of yeast. The separate portions of 20 gm. each were weighed into flasks and a sufficient number of flasks provided so that observations on each yeast in each gas could be made at suitable intervals extending over a period of six days. The results are given in Table VII., and are supplemented by observations of the fermentative power of the yeasts at different times and also of the lag phase period as measured by their reproductive capacity (Table VIII.). Observations made of the changes taking place both with regard to outward appearance and aroma were interesting and instructive. Washed yeast retained its original appearance practically unaltered throughout a six days’ storage, while un washed yeast after two or three days showed tendency to liquefaction and in most cases after four or five days was completely liquid. The odours presented another differentiation, as unwashed yeast gave off an aroma of pleasing fragrancy, tinged with higher alcohols, esters and acetic acid, while washed yeast developed and retained a rather offensive musty odour. These changes were distinct and characteristic, and gave reliable qualitative evidence of the behaviour of the yeasts.

Another important point concerning yeast in general was observed early in the course of the present work, namely, that when ordinary brewery pressed-yeast is allowed to lie exposed to the air at room temperature it very quickly turns brown on the surface. This is generally assumed to be due to oxidation, but it was found that this is not the case. When moist air is passed over ordinary brewery pressed yeast no discolouration takes place until after about three days when the usual darkening due to autolysis occurs. If, however, the air is dried prior to being passed over the yeast the usual browning quickly appears, showing that this phenomenon merely results from drying and not oxidation.

Whatever the analyses (recorded in Table VII., Figs. II. and III.) indicate it would appear quite reasonable to assume from the results obtained that any changes which have taken place in the yeasts stored under the different conditions of experiment are of a similar nature, but that the rate of change had varied within fairly wide limits. How far we are justified in this assumption will be considered more fully in subsequent work where attempts were made to determine the products of auto fermentation under conditions somewhat similar to those in the experiment under discussion. Considering the results seriatim it will be seen in the case of the acidity values that there is a marked difference between the washed yeast when stored in air or carbon dioxide. In the case of the yeast stored in the presence of nitrogen gas the acid figure has increased at a slightly greater rate than the air stored yeast, but is still much less than that in carbon dioxide. With regard to the unwashed yeasts there is very little difference in the amount of acid produced in air and carbon dioxide, but the nitrogen stored yeast is less acid. Coming to the nitrogen figures (both “total” and “formol”) there is very little difference in the amounts dissolved by alcohol in the case of the washed yeasts. Unwashed yeasts stored in air or carbon dioxide give practically the same results as was the case with the total acid, and again the “total” nitrogen in the yeast stored in nitrogen gas is less than the other two gases. Taking the whole of the above results collectively it will be seen that with one exception, i.e., the acid content of the washed yeast stored in carbon dioxide, the amounts of acid, “total” nitrogen and “formol” nitrogen are greater in the unwashed than the washed yeast, as determined by the prescribed methods of analysis. It now becomes fairly obvious that there has been a remarkable change in the behaviour of yeast which has been subjected to the simple process of washing with water. Whether the acid has been derived from the nitrogenous or carbohydrate content of the cell may be a matter of some moment, but the differences in the amount of “total” and “formol” nitrogen show that there has been a more rapid degradation of the nitrogenous constituents in the case of the unwashed yeast. Another rather striking feature is the influence of nitrogen, particularly noticeable with the unwashed yeast, when compared with the same yeast stored in the other gases. It may be accepted quite reasonably that nitrogen is a true inert gas under these conditions, and that in its presence the anerobic auto-fermentation will follow a natural course. Whatever be the nature of the substance which is removed or altered in composition when yeast is washed with water, it is a potent factor in auto-fermentation as indicated by these methods of analysis. Its action is accelerated by oxygen and carbon dioxide, the former gas possibly bringing about an oxidation of certain protein molecules which would be a prelude to the action of the “unknown.” If that were the case, however, why does the action proceed with such facility in the presence of carbon dioxide? Carbon dioxide may have a protective influence on the “unknown” and while it is possible that the separate effects of oxygen and carbon dioxide are equal it is not likely. The work of Harden and Rowland {loc. cit.) shows that the auto-fermentation of glycogen proceeds whatever the nature of the surrounding gas, and we also know that a considerable amount of oxygen is adsorbed by washed pressed yeast and presumably unwashed yeast. The precise mechanism of the changes under these conditions is not quite clear, but it would seem that glycogen is ultimately transformed into carbon dioxide and water.

As the main object of this work is an attempt to elucidate the causes of the lag phase in yeast growth, it would be practically useless unless correlated with determinations of the changes in the vitality of the yeast under the conditions of storage. The rate of reproduction must, of course, be the final measure in determining this lag phase, but a valuable supplementary aid is the estimation of the fermentative power of the yeast from time to time. The fermentative power of yeast is also of obvious practical importance in connection with the storage of yeast. The yeasts as used for fermentative power determinations were also examined for dead cells by methylene blue staining. It will be seen from Table VIII. that certain yeasts have no fermentative power, and yet the dead cells do not exceed 60 per cent. These results made us suspicious of the reliability of the methylene blue staining method, and so we thought it advisable to investigate its accuracy by direct plating methods. As we purpose publishing a special note on this particular subject, we do not enter into details of the results obtained, but we may say that we found the methylene blue staining method failed under the condition of our experiments, and it is probable that in the later stage of storage referred to the cells were practically all dead. Unfortunately, this was discovered too late to apply except in only one instance in subsequent recorded work.

A difficulty arises in estimating the lag phase because it is obvious that if the pro portion of dead cells is high the apparent lag in growth is erroneous and any calculation of the lag period must be corrected for dead cells. The figures in Table VIII., though not strictly accurate as regards the actual number of dead cells, indicate the enormous destruction of yeast and a great increase in the lag phase of the living cells when stored under the conditions of experiment.

We have just seen that the changes taking place in resting yeast are different when the yeast is washed previous to storage. It is evident that the water is washing away, dissolving or dialysing something from the yeast which when present greatly enhances its autolysis. The nature of these differences is such that washing seems to have a preservative action and to prolong greatly the life of the yeast and so it becomes of first-class importance to discover, if possible, what happens during the washing. Certain points which were thought might furnish an explanation of the observed difference in the two yeasts and which will be discussed in turn are: (I) Is it the removal of a sub stance complementary to the enzymes, or a toxic substance; if so, can it be added back to yeast with its usual effect and is it destroyed by heat. (II) Is it the removal of alcohol or other product of the metabolic changes. (Ill) Is.it the removal of something adsorbed on the surface of the yeast which, when present, causes a clogging of the respiratory functions of the cells. (IV) Is it an alteration in the hydrogen-ion concentration of the cell content with consequent change in the action of the enzymes, and (V) Is it an alteration in the course of auto-fermentation?

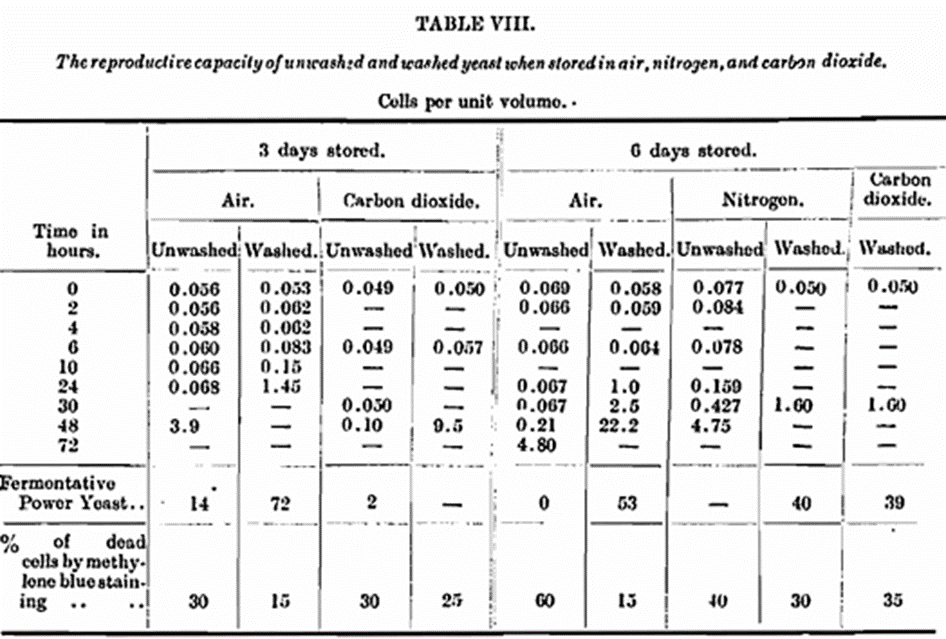

It has been shown that temperature has a decided influence on the enzymic changes of yeast during storage with the consequent development of a lag phase in growth. Considering that washing ordinary brewery yeast with water appears to retard the action of the enzymes responsible for these changes, and as the enzymes cannot be washed from the inside of the cells, the question arises as to whether the washing process removes the complementary substances. We know that washed and unwashed yeast have practically the same zymatic activity as measured in the Slator apparatus, but we have no experimental proof as to the activity of the endo-proteolysts. To prove the presence of the complementary substances of such enzymes is no easy matter but this does not preclude the possibility of their existence. From Tables IX. and X. it will be seen that adding an aqueous extract of yeast to washed yeast does not produce the autolytic effect noticeable during the storage of unwashed yeast in the pressed state, but this is not conclusive proof as the very act of diluting with water may be the means of destroying such substances if they were present. Similarly, as regards substances of a toxic nature these also might be destroyed during the aqueous extraction. That substances having a toxic influence on yeast are possible has been shown by Fernbach (Compt. rend., 1909, 149, 437-439) who prepared a weak acid extract of yeasts. Vansteenburge (Ann. Inst. Pasteur, 1917, 31, 601-630) found small quantities of tyrosine and leucine in pressed yeast, sub stances which he states are toxic to yeast. Other similar instances might be quoted showing that the deterioration during storage of unwashed yeast might be explained by the presence of toxic substances. We have prepared an extract by the method suggested by Fernbach from our yeast but found that it had no effect when added to washed yeast under our conditions of storage. Of course, it is not suggested that the above citations are exactly analogous to the issue at present under discussion. The toxic substance which we suggest as being a possible cause of the rapid deterioration of unwashed yeast is not necessarily a by-product of fermentation or yeast degradation, but is in fact more likely to be inherent to brewery yeast, such as a substance abstracted by the yeast from wort and in loose combination with some constituent of the yeast and which might be readily destroyed by mere dilution with water.

One of the earliest experiments was to prepare a strong aqueous extract of yeast. This was done by mixing equal quantities of yeast and water, standing half an hour and filtering through a Buchner funnel. The filtrate was again mixed with an equal weight of yeast and again allowed to stand for half an hour before filtering. This was done three times in all. The resultant solution was divided into two portions, one of which was left untouched, and the other one heated to boiling point and cooled. Some washed pressed yeast was then added and kept for 24 hours in contact with each of the two extracts. The yeasts were then pressed and along with blanks of washed and unwashed yeasts submitted to the usual storage test. The two treated yeasts behaved exactly as washed yeast (Table IX.), showing that the water-soluble matter from yeast when added back under the above conditions was without effect.

Another experiment on similar lines was carried out where some washed pure culture yeast was stored in the extracts for three days, and at the end of that time small seeding were made in hopped wort and the rate of reproduction determined but the extract had no effect. Again, a quantity of the extract was added to some hopped wort, and this used as a medium for determining the generation time of fresh yeast, but the results were negative.

A kilo of yeast was extracted with a litre of water, filtered on a Buchner funnel and washed on a filter by a further 250 cc. water. The combined filtrates were then concentrated at 30-40° C. under reduced pressure. The resulting extract was such that 100 cc. = 300 gm. yeast. It was divided into two portions, one of which was boiled and cooled, while the other was kept as unboiled. The effect of storing yeast in the extract was tried, 50 gm. washed yeast in each extract being allowed to stand at room temperature for 17 hours. The yeasts were pressed and stored under the usual conditions and controls of washed and unwashed yeasts were carried out at the same time. The results showed that there was no difference between the two treated yeasts and the washed yeast. As stated previously, the general appearance and aroma of the yeasts during storage is always a reliable index of the analytical results. In this instance the extract-treated yeasts and the washed yeast remained much about the same in appearance and retained their “dry” and crumbly state throughout. The unwashed yeast as usual turned liquid about the third or fourth day. The results are recorded in Table X. and the analysis of a concentrated extract similar to that described is given in Table XI.

The fact that all the above results were of a negative character is not, as stated before, conclusive proof of the non-existence of a toxic or complementary substance in the unwashed yeast for apart from other considerations, the mere addition of water to yeast and consequent dilution of its soluble matter may be in itself sufficient to destroy the potency of the substance or substances which are the causes of the changes under review.

Before leaving this part of the question as to what is removed from yeast by washing with water let us consider what the constituents of the cells are likely to be after the yeast has been left in contact with its pressings for a short time. The nutrition necessary for the maintenance of the life of yeast during this stage is not by any means the same as during active growth in hopped wort or other nutrient media. During storage there will be an accumulation of by-products which the yeast will eventually excrete but which in the pressed state it is unable to get rid of. If the washings of this yeast contain substances of the nature of excretory products it is by no means surprising that they are not re-absorbed when added to washed yeast. Against this view is the fact, which was proved experimentally, that new yeast when seeded into an invert sugar solution containing the necessary mineral matter and the aqueous washings of brewery pressed yeast, developed vigorously. In this case, however, the yeast is in active reproduction with readily available carbohydrate present, conditions very different from those obtaining during storage and further the capacity of yeast for selecting its food requirements cannot be overlooked. Again, supposing the by-products of metabolism were of a toxic nature it does not necessarily

follow that these toxic bodies will not be further proteolysed and changed into non-toxic substances prior to being excreted naturally by the yeast or washed away from the yeast on treatment with water.

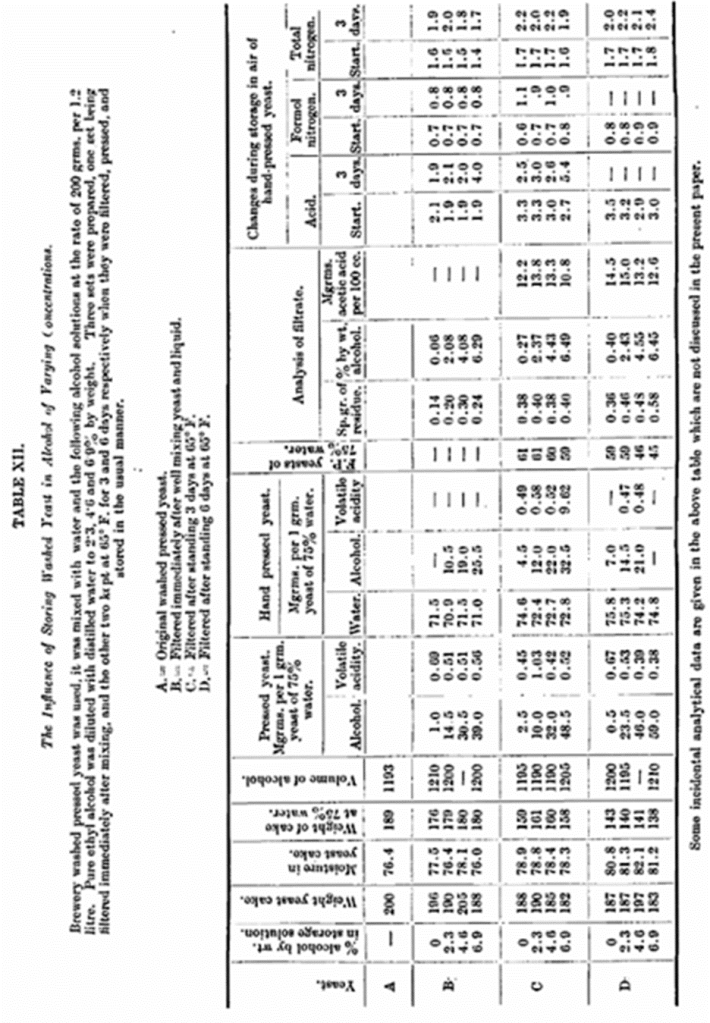

II. One of the most noteworthy differences between unwashed and washed yeast is that the washing almost entirely removes both the interstitial and internal alcohol, e.g., a specimen of yeast before washing contained 31·5 mg. alcohol, per 1 gm. of pressed yeast, while the same yeast after washing only contained 3·5 mg. To ascertain the influence of the removal of alcohol an experiment (Table XII). was arranged, washed yeast being steeped in solutions of varying alcohol concentrations from which on subsequent pressing, yeasts of different alcoholic content were obtained. These yeasts when stored under the usual conditions did not exhibit any noteworthy difference which points to the conclusion that the presence of alcohol per se was not the cause of the differences under consideration.

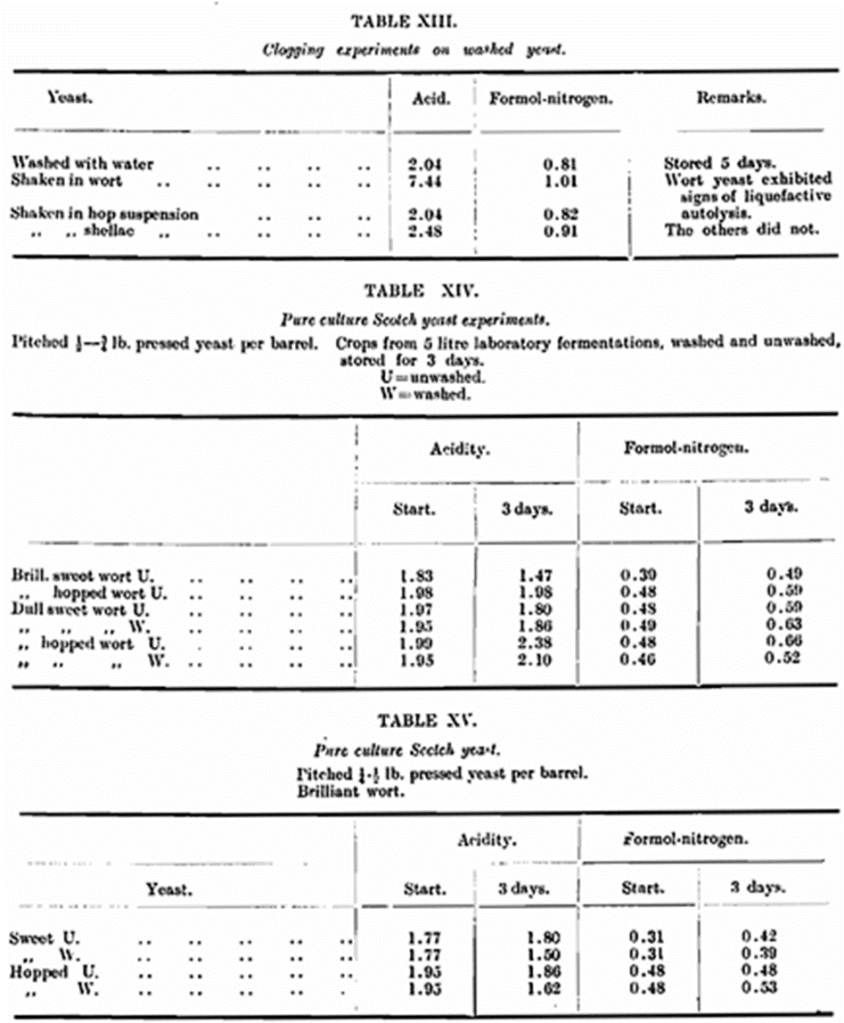

III. A few simple experiments were carried out to see if clogging of the yeast could be affected and if such would induce the same effect as occurs in an unwashed yeast. Fresh washed yeast was shaken with:

(a) Very cloudy wort.

(b) An aqueous colloidal solution of hops.

(c) A colloidal solution of shellac.

After shaking and standing for about an hour the yeasts were filtered off, and in all cases the nitrates were brilliant, showing that the colloidal particles either had been precipitated, adsorbed on the yeast, or had been rendered truly soluble, the latter being a most unlikely contingency. These yeasts were now stored under our prescribed conditions. The shellac and hop treated yeasts behaved exactly as the normal washed yeast, but the wort yeast increased in acid content and showed a greater proteolysis. During the initial contact of the yeast and wort a very vigorous fermentation occurred even in one hour of standing, so that this fact and others mentioned earlier must be considered in interpreting the result of this experiment.

Following this result further work on the influence of the fermentation medium seemed necessary. Accordingly, 5-6 litre fermentations of (1) dull hopped wort, (2) brilliant hopped wort, (3) dull sweet wort, and (4) brilliant sweet wort were carried out. Since sweet wort was being used it was necessary to ferment with pure culture yeast, so a large quantity of this was worked up in the usual way. The pure culture was isolated from the brewery yeast which forms the subject of the bulk of our work. The worts were pitched with about ¾ lb. pure (pressed) yeast per barrel. After 3-4 days the crops were collected and each divided into two portions, one was kept as unwashed yeast, the other was washed with water in the usual way. The standard storage of the eight yeasts was then carried out. The results were surprising, for the differences between the yeasts were negligible and, in all cases, they behaved as washed yeast. (Table XIV,). Other laboratory fermentations using pure culture yeast, gave similar results, while parallel experiments using brewery yeast as the pitching yeast gave crops which exhibited the now well-known washing effect. (Tables XV., XVI. and XVII.). The obvious conclusion to be drawn is that the peculiar property possessed by brewery yeast of autolysis when stored unwashed must be a cumulative effect due to the continuous production in presence of the colloidal substances of hopped worts. The pure culture yeast has likewise been through a great number of generations in wort of similar composition, except that it is always brilliant and therefore it might well be that the cumulative effect of the slight haze of brewery wort is the factor which has brought on this change. One experiment is not always sufficient evidence to prove any statement, but the fact remains that a laboratory fermentation with brewery yeast in very cloudy wort, and one in the same wort filtered brilliant produced yeasts which autolysed readily, but the one from the cloudy wort did so at a higher rate. Still, we do not mean to infer that the mechanism producing the cumulative effect of which we speak is simply of a clogging nature. Such an explanation would not fit all the facts, and moreover it is rather difficult to understand why a simple washing should completely remove the clogging material which was insoluble in the first place. It is a possibility, however, that contact with the yeast has effected some obscure change in this clogging material so that when amply diluted with water it forms a true solution.

Another known difference between laboratory brilliant worts and brewery hazy worts is the presence of copper compounds in the latter. Experiments showed, however, that our conditions of washing only removed a small amount of copper from the yeast— about 4 per cent, of that present—from which we may infer that the presence of copper is not the direct cause of the differences. At the same time, we must realise that the copper is probably adsorbed on the yeast as a copper protein complex and it is possible that this is decomposed by the washing process.

IV. Still in quest of an explanation our ideas were again focused on the popular and ubiquitous “hydrogen-ions” in the hope that the concentration of these in the internal content of the cell might provide a clue to the problem. Since the endo-proteolysts are not removed from yeast by a simple washing it follows that the action of water renders the enzymes inactive in some other way either directly or indirectly. One such action might result in a change of the internal hydrogen ion concentration of the cell. It seems possible that by plunging yeast into a large volume of water the internal composition will be changed and a new equilibrium between the complexes of the cell established. Depending on these changes the liability of the cell to enhanced or decreased keeping qualities will vary. Once more difficulties arise. It is not an easy matter to determine with certainty the hydrogen-ion concentration of the inside of a yeast cell and measure the changes occurring under treatment. Ten gm., pressed yeast were stored for 10 hours at temperatures ranging from about —30 to —80oC. This treatment made the yeast partially liquid. It was made to a known volume with water and then centrifuged. The solids were 0·82 gm. per 100 cc. (=1/3 total dry weight) and the pH of this juice was found to be 6·2.

It has been observed that the walls of yeast cells can be ruptured by rubbing them between glass surfaces such as between an ordinary microscope cover-glass and a slide. If a sliding or lateral motion under steady pressure be set up between the surfaces many of the cells, at any rate are, ruptured, as an examination under the microscope reveals. After performing the rubbing operation on some yeast, a drop of suitable indicator was added, and by making a comparison against buffers an approximate pH was found. Usually this was round about 6·0 and always showed less acid than when tested before rubbing. Another method employed was to drop some yeast into boiling water, cool and centrifuge. The pH of the clear liquid from both unwashed and washed was 6·3.

An effort was next made to alter the internal hydrogen-ion concentration of the cell by immersion in suitable liquids. It was decided to suspend the yeast in water and adjust the hydrogen-ion concentration of the mixture by the necessary quantities of sodium hydroxide and hydrochloric acid instead of using buffer solutions as in previous work on this question. As a preliminary 5 gm. of yeast and 50 cc. water were mixed and a suitable indicator added. Acid was now run in until after standing a short time the pH remained unaltered at 3·5. In the same way the amount of soda to get pH 7·0 was arrived at. Intermediates of pH 4·5 and 5·5 were also prepared. Larger quantities of yeast were mixed with water and adjusted to pH 3·5, 4·5, 5·5 and 7·0. These mixtures were kept for 48 hours and then filtered. The yeasts were hand-pressed and stored. The behaviour of the yeasts was identical in all cases and was normal to washed yeast. The hydrogen-ion concentration of the yeasts after pressing and before storage were first ascertained by the rubbing method. These did not vary much, although there was a distinct, though small difference between the two extremes in which the concentrations, were approximately 5·8 and 6·1 respectively. Two gm. each yeast was dropped into boiling water, cooled and centrifuged and the pH of the clear liquids determined colorimetrically. They were 6·2, 6·3, 6·4 and 6·5. The filtrates from the yeasts after storage were 4·5, 5·5, 6·3 and 6·9. This experiment may not fulfil its original intention, and though the methods we were compelled to employ are by no means perfect, it certainly shows that the internal hydrogen-ion concentration of yeast is not upset by such drastic treatment and therefore mere washing is not likely to have such effect. (Table XVIII).

Still one further point bearing on this subject was investigated, and that was to find out the behaviour of yeast when grown in worts of varying hydrogen-ion concentration. Some wort was adjusted with sulphuric acid or sodium hydroxide to obtain worts of

pH 3·4, 4·4, 6·0 and 7·5. The comparatively low pitching rate of ½ 1b. unwashed pressed brewery yeast per bbl. was selected in order to get a relatively large number of generations and still be within brewery conditions because we have shown in a previous communication that the progeny of yeast inherits in a marked way the characteristics of the parent cell. After fermentation the pH of the beers was 3·4, 4·0, 4·4 and 4·6 from which it is obvious that the yeasts produced in the media must vary in some way. By the rough methods previously employed no very distinct differences could be observed in the internal hydrogen-ion concentration of the yeast. The yeast crops were each divided into two portions, one kept unwashed and the other washed. They were then stored in the usual manner. Their behaviour under storage was not altogether satisfactory because after 4 or 5 days, putrefaction occurred. The earlier observations indicated that there were not any noteworthy differences, although the general tendency was that yeast grown in the less acid worts had the lower death rate.

We have good reason, based on much experimental data, to think that the inside of living yeast cells has a pH in the region of 6·0. Now as Dernby has shown (Biochem. Z., 1917, 81, 109) that the optimum for yeast “pepsin” is pH 4·0-4·5 we may conclude that the inside of a healthy yeast cell is not favourable to its action. This is reasonable because it is by no means likely that a yeast cell is without means of self-defence. When unwashed yeast is stored, it is noticed that the production of acid generally precedes the production of amino-nitrogen. The amino nitrogen curve does not really show an upwards tendency until the acidity of the yeast is roughly three times its original. This represents a large endo-cellular production of acid, probably quite sufficient to change the internal hydrogen-ion concentration of the cell (under conditions of dry storage) and thus account for enhanced proteolysis.

V. With a view to finding how far the course of the auto-fermentation was altered by washing yeast with water an exhaustive experiment was arranged, the results of which are detailed in Table XIX. A supplementary experiment as regards alcohol and carbon dioxide production is recorded in Table XX. and Fig. IV. Considering the alcohol figures in the first of these two tables it will be seen that in the case of the ordinary unwashed yeast there is a steady production during the first 41 hours followed by a continuous decrease up to the termination of the experiment at 120 hours. In the case of the washed yeast, which started with only one-ninth of the alcohol present in the ordinary yeast, the alcohol remained constant for the first 41 hours and then very rapidly fell to zero. The volatile acid shows a marked increase in the case of the ordinary, whereas in the washed yeast the quantity decreases and finally vanishes after about 50 hours. As regards the total acid the differences are much more striking; in the case of the washed yeast, it may be said that there is no production, whereas in the ordinary yeast the acid increases rapidly at first and steadily thereafter until the amount present is quite considerable. It is obvious that the proteolytic changes as indicated by the amino nitrogen figures, with the exception of the slight increase in the first-time interval of 17 hours, remain practically in abeyance until about the 41st hour, after which there is a distinct increase in the case of the ordinary yeast. With regard to the proportion of dead cells they were estimated by the methylene blue staining method. In the case of the last estimation in the ordinary yeast, we made an actual estimation of the proportion of living cells by a plating method. The result of this was that we found that only 5 per cent, of the cells were alive. The non-staining is due to the presence of certain substances which produce the well-known leuco-compounds. At what stage during the storage of yeast these compounds are present in sufficient concentration to vitiate the results recorded we are unable to say. As regards the washed yeast the final figures as ascertained by both staining and plating methods were the same. Taking into consideration the results obtained under parallel storage conditions and recorded in Table XX. it is evident from the carbon dioxide respiration figure that death had ensued in the case of the majority of the cells in the unwashed yeast at between 30 and 48 hours, whilst in the case of the washed the evolution of carbon-dioxide steadily continued up to 200 hours, at which time the experiment was terminated. The results give an undoubted affirmative answer to the question as to the effect brought about by washing, viz.: Is it an alteration in the course of auto-fermentation?

It is evident now that the effect of washing is to remove the accumulation of harmful by-products and to dissolve or alter toxic substances, thus conserving the vitality of the yeast and enabling it to break down its carbohydrate reserve into the harmless pro ducts, carbon dioxide and water, in such a way as to obtain energy for the maintenance of its life. On the other hand, the unwashed yeast in the pressed state being unable to get rid of its by-products and in addition suffering from the presence of toxic substances and possibly containing its full complement of co-ferments, produces more poisonous by products which lower its vitality, death ensuing with much enhanced velocity, this being followed by rapid liquefactive autolysis.

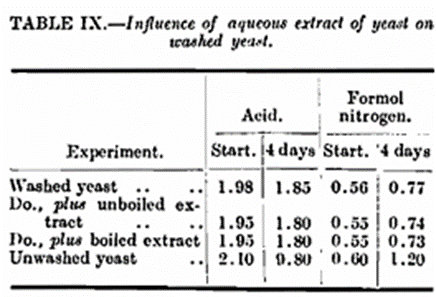

Summary.

The suitable presentation of the results obtained in this investigation has been difficult owing to the necessity of including so much experimental detail. It seems, therefore, advisable to give a summary of the salient features and to discuss them from the standpoint of modern views of fermentation. First, let us consider the changes taking place in brewery yeast (unwashed) during storage at 65° F. There is a considerable evolution of carbon dioxide; according to Harden and Rowland (loc. cit.), when the surrounding atmosphere is nitrogen or carbon dioxide, a corresponding amount of alcohol is produced. These authors show that the alcohol-carbon dioxide ratio is near the usual 1·00 : 0·96 of ordinary alcoholic fermentation, under these anaerobic conditions, but that when the yeast is stored in a current of air, this ratio does not hold. Our results show that the alcohol increases to a maximum of about 5-6 per cent, on the pressed yeast, and then disappears, and, further, that the ratio of the alcohol to the carbon dioxide produced in the same period does not coincide with the equation for normal alcoholic fermentation. The evolution of carbon dioxide is virtually over after about 40 hours, as is also the production of alcohol. It is about this stage also that the death-rate begins to rise rapidly, that liquefaction becomes noticeable, proteolysis increases, and that, in general, the usual after-death phenomena occur. The rate of death itself indicates a premature demise, due to certain causes, and these appear to be primarily the accumulation of the by-products of fermentation which are detrimental to the vitality of the cells. The protracted presence of acetaldehyde particularly evident in the earlier stages of auto-fermentation, alone indicates diversion from the ordinary course of fermentation, yet, paradoxically, it supplies strong evidence in favour of the theory that acetaldehyde is an intermediate product in alcoholic fermentation. It is obvious, however, that in the beginning the fermentation is almost normal but, because of being stored in the “dry” state, the cells are unable to dispose of their by-products, and thus internal poisoning occurs. Carbon dioxide and alcohol we know to be noxious to yeast, but while the former is carried off by air, the concentration of the latter inside the cell is increasing from its normal of about 4 per cent, up to a maximum 8-9 per cent., and this may quite well be lethal under the conditions. On the other hand, there is good evidence for the assumption that other by-products, smaller in amount, but more potent in effect, are produced, coupled with the probable presence of a body having a toxic effect (or of a true toxin). Other contributory causes are the extremely small amounts of “copper-protein” found associated with yeast, possible clogging of the outer cell layer by the cumulative effect of fermentation in brewery worts, and also the presence of higher alcohols and esters. In addition, there is a marked accumulation of acid, either a normal intermediate or an end product of metabolic changes. This might be due to interference with the activity of the carboxylase, resulting in an accumulation of pyruvic acid. Direct experiment has shown us, however, that immediately after washing the carboxylase content is not altered. We have, so far, been unable to find an opportunity to follow up what happens on storage in this connection. If the acid were pyruvic (or other ketonic acid) it would amount to 50 per cent, more than the weights given in the tables (which are calculated to acetic) that is, 15 to 20 mg. per 1 gm. pressed yeast, or 15 to 20 mg. per 700 mg. water, which is between 2 and 3 per cent, internal concentration. This may not be an amount large enough to destroy the cell, but at least it must have a contributory effect to the general result, even if it be an indirect one, but modifying the internal hydrogen-ion concentration of the cell to a condition more favourable to the action of certain enzymes which break down the protoplasmic structure. That the endo-proteolysts of yeast are no exception to the general rule that proteolytic enzymes act best in slightly acid solution has been shown by various workers, so that a very necessary part of the liquefaction of yeast must be a preliminary intracellular production of acid. We have seen how resistant yeast is to the external influences of solutions of varying hydrogen-ion concentration, and how it strives to maintain an equilibrium under all conditions. That this equilibrium is in the region of pH 6·0-7·0 seems to be correct, especially when the evidence of others is taken into consideration, for example Euler and Nordlund (Z. Physiol. Chem., 116, 229-244) found that the effect of hydrogen-ion concentration on the esterification of phosphoric acid inside the cell is very marked, the most favourable being pH 6·2-6·6. This is strong indirect evidence that the death of the cell must precede autolysis, or, if preferred, liquefaction. Moreover, it has been observed that in every instance where an appreciable proteolysis as measured by formol titration takes place, there has been, first of all, a marked increase in the acidity of the yeast. Increase of acidity, however, does not invariably lead to proteolysis; in such cases which we have observed only when dealing with washed or specially treated yeast, the treatment by removal of something from the cell conserves its vitality either directly by removal of definite toxic substances, or indirectly by so altering the nature of its auto-fermentation that it no longer accumulates poisonous by-products, or by both actions. The life time of such treated yeast is prolonged until the reserves are depleted, and when death ensues such yeast does not exhibit the phenomenon of liquefactive autolysis observed in the case of untreated yeast. In addition to the effect of the harmful by-products just discussed, there is also the possibility of the influence of other toxic substances. The evidence as- regards the existence of which, whilst unsatisfactory, indicates the probability of their presence in brewery worts. The points just discussed help to explain why yeast keeps better in its own pressings, in beer or in water—because under such conditions free diffusion of by-products is possible.

Now, if yeast is washed with water prior to storage in air entirely different phenomena result, and certain of the changes already indicated are diverted, retarded or completely prevented. The evolution of carbon dioxide proceeds at an even greater velocity than in unwashed yeast, and the continuity of its evolution indicates that the yeast is living and respiring normally. There is no alcohol produced, the glycogen therefore does not undergo alcoholic fermentation, any traces of alcohol remaining after washing, rapidly disappear. The formation of acetaldehyde during storage has been detected, but the amount is slight, less than from the same yeast before washing. The death rate is low, and quite consistent with the respiration of carbon dioxide when it is considered that the yeast is exhausting its carbohydrate content with fair rapidity. There is practically no acid produced, the amount of proteolysis is small, and there are no higher alcohols or esters formed.

What, then, has the washing with water clone for the yeast so that its lifetime is increased so greatly? In the first place, water will remove all the soluble matter from outside the cell, and probably a certain amount from inside. This will include the small amount of excretory products already existing, for, although the yeast is assumed to be fresh, i.e., newly skimmed, there is bound to be a certain amount of down-grade products present. The alcohol, easily detected and estimated, is certainly removed practically in its entirety, and we have seen that subsequent events do not include its further production. Therefore, the injurious effect of the excretory products originally present is removed. We may ask why there is not a further production of these same products. The non-production of alcohol may provide an answer. Obviously, we have altered the course of the auto-fermentation, as no alcohol is now produced from the glycogen of the cell. We know that washing removes appreciable quantities of phosphoric acid, this might come from hexose-phosphate, and the interference with the concentration of this body might, of course, alter the cycle of changes, although the reason why is not clear, as a lessened rate of fermentation would be the only expected result of a diminution of the phosphoric content. It is

obvious, however, that this cannot be the sole reason for the promotion of the keeping qualities of washed yeast, because washed yeast keeps equally well in nitrogen as in air, and only slightly less so in carbon dioxide. Further, we know that alcohol is produced when the surrounding atmosphere is nitrogen or carbon dioxide. Therefore, although the hexose-phosphate reaction may be interrupted in presence of air we must look further for the explanation of the full effects. The next step is the possibility of the reductase of yeast being upset by the conditions. The exact manner in which this enzyme functions is not yet clear, in fact the evidence is such that it cannot be regarded as an enzyme proper, but rather as an oxidisable substance capable of losing hydrogen, and thus being enabled to act as a hydrogen donator. Harden and Norris (Biochem. J., 1914, 8, 100) have shown that dried yeast and zymin lose their power of reducing methylene blue when thoroughly washed, but that this power is restored by the addition of the washings and certain other substances. From their results they showed clearly that the reaction was highly specific, and it was further presumed that the active substances which restored the power of reduction were capable of acting as oxygen acceptors (or hydrogen donators). Bearing in mind the findings of Harden and his colleague, let us trace the probable course of the auto-fermentation of washed yeast, according to the pyruvic acid theory of alcoholic fermentation suggested by Kostytschev. There is, first of all, the hydrolysis of the carbohydrate glycogen to a hexose which, we will presume, is dextrose.

Now follows the formation of hexose phosphate, with the subsequent liberation of a hexose, which we assume to proceed normally.

The next step is the formation of pyruvic acid from the hexose, and this reaction involves the liberation of 4 atoms of hydrogen.

By the action of the carboxylase of yeast, pyruvic acid is decomposed into carbon dioxide and aldehyde, the latter being then reduced to alcohol.

The latter reduction requires four hydrogens for its purpose, and the presumption is that by means of a hydrogen carrier the four hydrogens set free in the formation of pyruvic acid are carried over for this reaction. Now if the hydrogen atoms were removed by a pre-destruction of the mechanism which would normally have fixed them for the subsequent reduction or by an oxidation process it would obviously explain why no alcohol is produced under the conditions. The fact that aldehyde was detected in washed yeast under these conditions is proof that the reactions proceeded to that stage, and from then it is probable that instead of the normal reduction of aldehyde to alcohol taking place, the aldehyde is oxidised to carbon dioxide and water.

The fact that acetic acid was not detected is no proof that the reaction does not proceed this way, because even though no precautions were observed for its detection it is extremely probable that a fixation method such as was used by Neuberg to detect acetaldehyde would be necessary. The further possibility that the oxidation is direct must not be overlooked. As stated by Harden the “reduction action” is highly specific, and it is thus possible that the hydrogen carrier is not produced until it is wanted, and that perhaps the pre-washing of the yeast has rendered the mechanism, which produces it, inoperative. In unwashed yeast as we have seen, the auto-fermentation of the reserves gives rise to alcohol and carbon dioxide, but since the alcohol- carbon dioxide ratio is not the normal for true auto-fermentation there is distinct evidence of the influence of oxygen on the hydrogen carrier. Accepting the above conclusions, we may see how far they apply to lag phase in growth of stored yeast. In the unwashed yeast there is a steady accumulation of by products which bring about rapid weakening of the vital functions, destruction of zymase, etc., and premature death. In the washed yeast, even though these by-products have been removed, and are not re-formed, the yeast in order to maintain life gradually depletes its reserves with consequent reduction in vitality. Hence, when such yeasts are placed into fresh wort, in the case of the unwashed, we can imagine that the surviving cells have first to expel the accumulated poisonous by-products, and then or concurrently to absorb the carbohydrate and nitrogenous matters necessary for re building their starved plasma; in the case of the washed yeast, though the by-products may be less in amount and toxicity, still the yeast has also to rebuild its depleted plasma. The length of the lag phase period must obviously be some function of the extent of the cell disintegration.

It is with very great pleasure we acknowledge our further indebtedness to Sir. J. S. Ford. As in previous communications he has again in characteristic fashion ungrudgingly extended to us the full advantage of his wide knowledge and experience. In concluding, therefore, we express our keen appreciation of all his most valuable assistance throughout the whole course of the work. We also thank Mr. J. B. Westwood and Mr. W. J. Mitchell for their willing help, in much of the manipulative work, and also Mr. A. P. Somerville, of the engineering staff, who prepared the curves and lantern slides.

APPENDIX

TABLES, CURVES AND EXPERIMENTAL METHODS.

One litre of sterile hopped wort contained in a 2 litre flask was fermented to completion with a pure culture Scotch yeast at 70° F. The wort was analysed before fermentation, and again after fermentation. The flask was set aside at room temperature for eight days, after which time the contents were again analysed. The old yeast was then seeded into fresh wort, and as a control a fresh culture was at the same time seeded into a similar quantity of wort. Estimations of the number and weight of cells present, the nitrogen assimilated and the degrees of gravity fermented were made in the early stages. An examination of the yeasts was made at the commencement of this fermentation, and it was found that there were 4 per cent, dead in the fresh yeast and 20 per cent, in the old yeast. The figures given in the table are not corrected for those dead cells, because it was difficult to arrive at a suitable figure for their weight, and also because such a correction if applied would be in favour of the old yeast.

The work connected with the next few tables was carried out with a pure culture of Scotch yeast. A large quantity of active yeast was grown overnight in hopped wort. The yeast was separated from the fermented liquid by decantation, and then washed once or twice with.sterile water by decantation, and then once in a centrifuge with its future storage liquids. It was then divided into the desired number of portions and the pre-arranged amount of storage liquid added. The proportion of liquid to yeast was approximately 100 cc. to 0·5 gm. pressed yeast. Except where otherwise stated the storage was done at 65° F. for 3 or 4 days. After the period of incubation, 100cc.portions of wort were seeded with the yeasts, the usual rate being about 1 cell per unit volume. These flasks were kept in a bath at 65° F. and were shaken at very frequent intervals. Counts were made at stated periods and from the results the number of generations produced was easily calculated. As this work is an investigation of the lag phase of yeast growth, that is, the time during which no reproduction occurs it seemed desirable to express the results in terms of this time. From the results of a great number of observations taken on the growth of the particular culture of Scotch yeast used, it has been calculated that the generation time (G.T.) for this yeast at 65° F. under favourable conditions as to aeration, agitation, food supplies, etc., is 4·3 hours. Needless to state the observations were made during the logarithmic stage of growth.

If then the number of generations produced in a fer mentation under similar conditions is multi plied by 4·3, the number of hours necessary to produce these generations under standard conditions is arrived at. This figure, deducted from the actual number of hours taken, will approximately give the lag phase period in hours. This cannot be absolutely correct, of course, as the seeding is complicated by the fact that all the cells are not of the same age, and therefore will possess varying lag phase periods. The number of dead cells also upsets matters a trifle. The latter, however, can be corrected for and in the following tables this has been done as far as possible. The results given in Tables III, IV, and V. are, of course, strictly relative in themselves, but it is not permissible to compare one set of results with another set without first considering other factors involved. The time of storage varies, as in Table V. it is 4 days against 3 days in the other two. Also, the degree of preliminary washing is certainly a function to be considered in spite of the remarks in the context of the paper concerning pure culture yeast. These figures are also given in the form of curves (Fig. 1) and show the marked influence of pre-storage in sugar solution of a yeast which has developed a pronounced lag phase. The difference between a washed and an unwashed yeast is also clearly shown.

Details of Methods or Storage and Subsequent Analysis.

Twenty gm. of hand-pressed yeast were weighed out and transferred into a 300 cc. Erlenmeyer flask fitted with a cork having a single hole and a small slit at the edge to act as a gas exit. Through the hole was fitted a right-angle glass tube reaching to within about an inch of the surface of the yeast. So arranged it was possible to connect these flasks in batteries, each flask being supplied with a gas-washing bottle containing water, and to pass moist air over the surface of the yeast at a regulated rate of approximately one bubble per second. After storing for the desired time at 65° F. 100 cc. of alcohol (Sp. Gr. 0·827) were pipetted into the flask which was then stoppered, shaken and allowed to extract overnight. This was later modified by washing the stored yeast into a 100 cc. flask with alcohol and finally making to 103 cc. After extraction, the contents of the flask were centrifuged and the clear solution used for analysis. Although the alcoholic extractions were always left standing overnight such a long time is not essential as it was found that the difference in values between an extraction for 3 or 4 hours and overnight was slight, but owing to its convenience the overnight extraction was adhered to throughout. We are aware that a good many other estimations could be made—notably the method by Willstätter and Waldschmidt-Leitz for amino-nitrogen—but as a preliminary we were content with the differences indicated by the methods outlined above. The results recorded in the tables are not intended to be accepted as absolute, but they are relative under the conditions indicated.

Total Acid, Formol-Nitrogen and Total Nitrogen.

Ten cc. were pipetted into an Erlenmeyer flask and 50 cc. CO2.free water and 2 drops phenol phthalein (0·5 per cent, in .50 per cent, alcohol) were added. The free acid was then estimated by titration against standard baryta. The same solution was used for estimating the formol-nitrogen for it was only necessary to add 10 cc. of neutralised commercial formaldehyde containing 1 cc. phenol phthalein per 100 cc, and then to continue the titration, bearing in mind Sörensen’s precaution always to add 2-3cc.baryta in excess of that required and titrating back the excess with standard HCl. This titration gives consistent results and good duplicates, if care is taken to maintain uniform conditions throughout. Theoretical results were obtained with a pure asparagin solution. While the changes as measured by this simple formol titration indicate the continued degradation of the protein molecule, the method cannot pre tend to be absolute because the amino bodies may be represented by both the mono-basic and the di-basic forms. Further, amino acids are not certain to be the end products of this particular chain of the degradation as the reduction might proceed further, or they may even form a substrate for amidase. The total nitrogen was estimated in 20 cc. by the standard Kjedahl method. The acid values are expressed in terms of acetic acid throughout the paper, but this has only been done for the sake of uniformity and it is not intended to imply that acetic acid is the only acid produced or even that it is produced in quantity. The relative value of the results are not impaired by this method of calculation. It has been found at different times in the course of the present work that washed yeast stored in a current of air loses acid and this is the case in the table under review. This loss may be due to oxidation, although the same yeast unwashed gains in acid under the same conditions, but that may be because in the latter case there is a continuous production of acid. The loss of acid in washed yeast is not a simple volatilisation because the same phenomenon is observed when the storage is carried out in flasks fitted with reflux condensers. No attempt had been made at the present juncture to identify the nature of the acid produced but from a few estimations recorded elsewhere the amount of volatile acid as acetic was only 0·08 mg. per 1 gm. pressed yeast or 2·8 per cent, of the whole, and even this quickly disappeared on storage.

The above figures of the numbers of cells are not corrected for the dead cells, as this was found impossible owing to the technical difficulties mentioned in the context, where the results are discussed. The fermentative power was measured by a modification of Slator’s well-known method, as used extensively by us in previous communications. In addition, a continuous production of acetaldehyde in the early stages was observed in both unwashed and washed yeast. It was detected both in the escaping gases and in the distillate from the entire yeast.

Estimation of Carbon Dioxide given off by Respiring Yeast.

Twenty gm. hand-pressed yeast were contained in a 300 c.c. Erlenmeyer flask, fitted with a rubber stopper through which passed a right-angle entrance tube dipping to within an inch of the surface of the yeast. Another right-angle tube cut flush with the bottom of the cork served as an exit. The air previously purified by being passed through soda lime, strong potash, and finally, water, was led over the yeast at the rate of about one bubble per second, and then through 20 cc. and 5 cc. normal potassium hydrate contained in a gas-washing bottle, and a calcium chloride U-tube respectively. A small wash bottle containing normal potassium hydroxide to exclude adventitious carbon dioxide completed the apparatus, which was immersed in a bath at 65° F. The carbon dioxide evolved at any given interval of time was thus easily estimated by washing the contents of each vessel containing standard alkali into a 250 cc. and a 50 cc flask respectively, with CO2 free water. Before making to volume, the carbonate was precipitated by the addition of 25 cc. and 5 cc. of N/l barium chloride. To ensure a minimum loss of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of the apparatus, the air current was slightly increased for about ten minutes prior to disconnecting, and was shut off completely during the operation of washing out and recharging with standard alkali. The titration of the filtered solution with N/10 hydrochloric acid completed the estimation. The control was 25 cc. N/l potassium hydroxide plus 25 cc. N/l barium chloride made to 250 cc., and filtered before titration. The volume of potassium hydroxide, and thus the weight of carbon dioxide given off, was easily calculated. If the interval of time between estimations was expected to be long the volume of standard alkali in the washing bottle was doubled. The volume of N/l potassium hydroxide in the calcium chloride tube used up by carbon dioxide never exceeded 1 cc. The alcohol was estimated at the stated time intervals, by distilling from water the contents of one of a series of flasks containing 20 gm, hand-pressed yeast. Slight variations in individual flasks are thus to be anticipated.

Discussion.

Mr. J. Stenhouse asked what effect had the lag phase of the yeast on the beer so far as brewers were concerned? Suppose that lag phase was an hour or two longer, did that mean that the final attenuations would be hung up, or the beer have to remain longer in the fermenting vessels. If it was desired to keep pitching yeast a little longer than usual did the authors recommend users of the Scott system to wash the yeast before putting it through the press?

Mr. F. E. B. Moritz said he was interested in regard to the question of the clogging effect upon yeast induced by cloudy wort. He knew of a brewery where great difficulty was experienced with the attenuations. The trouble was traced to the mash-tun — the mash-tun runnings being very cloudy, due to the bad fittings of the mash-tun plates. He had concluded that the yeast was being strangled during fermentation on account of the fact that the wort must have contained a great amount of amorphous matter carried through from the mash-tun. A change of yeast was tried and worked quite well the first time through, the final attenuations being satisfactorily low. But the second time through, the fermentation again stuck. New mash-tun plates were put in and the wort ran bright in a very short space of time; the fermentations then went quite normally and the beer was satisfactory. It would therefore seem that the thick runnings due to bad filtration in the mash-tun affected the action of the yeast during fermentation. He was un decided as to whether the ill effects of a cloudy wort on yeast were mechanical or toxic, or both.

Mr. W. J. Watkins said that at one time he had been troubled with a bacillus in the yeast, and he had endeavoured to get rid of it by tartaric acid treatment of the wort, which was quite successful. The yeast was clean and white, and there was no amorphous matter on the cells after treatment. For the first two or three times through, it showed a marked increase in fermentability and the lag phase was certainly decreased: the yeast gradually became normal. At the present moment he was using the Scott process and he found that if the yeasts were coming off in a dirty state with a lot of amorphous matter present, they did not keep so long as when they came off clean. He had had cases where the yeast had broken down after about 48 hours in the Scott press, although it had been chilled to about 33° F. He had also had instances where the next lot from a very similar type of beer had kept quite well for a week; and certainly, he had found that in the cases where it had broken down, there was a much higher percentage of amorphous matter present when those yeasts were skimmed. He had tried washing yeasts some years ago in a manner similar to that described by the authors. The effect was the same as was stated in the paper; but after three or four times through, the yeast weakened and the fermentations were inclined to stick. It seemed, although no experiments were carried out to prove it, that the yeast after washing was able gradually to take up more amorphous matter than before, and it required a frequent washing.

Mr. C. A. Warren asked the authors if they were washing with a water with its normal content of air in solution what effect would that have? He believed that Horace Brown had found the oxygen in ordinary wort was used up by the yeast in about two hours. He thought perhaps the oxygen in the water had a tonic effect on the reproductive faculty of the yeast, because that faculty was easily affected by quite small matters. He would like to know whether the authors had tried washing with a water that was absolutely free from air or whether they washed with the ordinary laboratory water.

Dr. J. H. Oliver said the authors had attributed the rise of original gravity in an ordinary pressing to be largely due to alcohol produced by the fermentation of glycogen, he

would ask whether they consider the small rise of original gravity obtained with a stone square pressing to be due to the absence of glycogen in that yeast. With regard to toxic bodies, which might affect a yeast, it had for a long time been the opinion in the laboratory, with which he was associated, that hop resin could behave as such a sub stance, and he thought that resin was the most obvious reason for the difference between brewers and bakers’ yeast, as regards auto lysis. He could confirm the authors’ experiments on the pH value of the yeast cell liquid, although he had found some yeasts to be as acid as pH 5.-

Mr. H. L. Hind said he would be glad if the authors could give them a little more about the bearings of these points on practice. He would like to know whether it was possible that any of the lag phase was owing to the hexose phosphate reactions.

Mr. Tait, in reply to Mr. Stenhouse, said he was afraid that until a washed yeast was used in the brewery it was almost impossible to answer the questions. However, he did not think it would make any difference whether the yeast was washed or unwashed. If the reproductive powers of a yeast taken from the brewery press and the same yeast after washing are determined it is found that there is no difference in the length of the lag phase period. It was only after these two yeasts had been stored for a few days that the lag phase in the unwashed yeast developed. If it were established that washed yeast gave a normal fermentation in practice then it would be better to store as washed pressed yeast instead of unwashed when it was necessary to keep the yeast for some time. In the meantime, it would be as well to keep the yeast in its pressings.

It was certain that phosphates were dissolved from the yeast on treatment with water as had been proved by an analysis of the washings (see Table IX).

In reply to Mr. Moritz, they were interested to hear his experience of the clogging effect and the fact that he got a marked benefit by a change of yeast. This would make one infer that it was certainly a case of a cumulative effect. They were very interested to hear from Mr. Watkins that in his experience pressed yeast sometimes went wrong in 48 hours and at other times it kept for about a week.

Mr. Watkins here stated that he had had one instance where the yeast became sloppy in 48 hours, and it was yeast with a skin in a very dirty state. He would explain that it was a skimming system, and the usual practice was to skim what was known as a dirty head, just as the yeast was commencing to come up, and he had found in this case that skimming had been omitted, and that the usual large amount of amorphous matter that was brought away with the first dirty head (which, of course, was not kept), was mixed with the yeast which went into the storage pressing. He had found that the best temperature to keep yeast in an impressed state was about 45°’ F.; below that temperature the effect was deleterious. But with pressed yeast, that temperature was quite useless. His own yeast would not keep at 45° F. in the pressed state, but would at 32° or 33° F.

Mr. Tait said that that was a point in favour of low temperature, because as shown in Table III. there was no question as to the influence of temperature on the storage of yeast.

The subject of the oxygen requirements of yeast was a very controversial one. When they carried out the different storage experiments the yeast got any amount of oxygen because they passed moist air over it, so he did not see that it was of any moment, whether they washed the yeast with air free-water or not.