MEETING HELD AT THE WHITE HORSE HOTEL, CONGREVE STREET, BIRMINGHAM, ON THURSDAY, DECEMBER 14th, 1911.

Mr. W. H. Evans in the Chair.

The following paper was read and discussed: —

Influence of Mashing Liquor on Extract Yield.

By R. L. Siau.

It has long been considered by English brewers that the liquor employed in mashing exerts a powerful effect upon the character of the wort produced as well as on that of the finished beer. Gypseous liquor, for instance, is credited with the production of worts that break well in the copper, and yield pale, clean-drinking, dry beers; whilst the presence of alkali carbonates, as typical of the chalk waters from beneath the London clay, is said to tend to the production of a more highly-coloured, fuller-flavoured beer. This belief has led many brewers to attempt, by addition of mixtures of salts, to produce from their home supply a colourable imitation of the well-waters of Burton, hoping thereby to obtain assistance in their endeavours to prepare a beer of similar character to that brewed in Burton. What measure of success has been attained in this way is not now my concern.

The point with which I wish here to deal is primarily the influence of the composition of the mashing liquor upon the amount of extract yielded by a malt; incidentally, differences in the composition of the resulting worts may be referred to, but they are only touched upon as being related to the main object.

The subject has already been dealt with more or less definitely by several writers, but only one of them, so far as I am aware, has approached it from the quantitative standpoint, and no one has pointed out the financial aspect of the question.

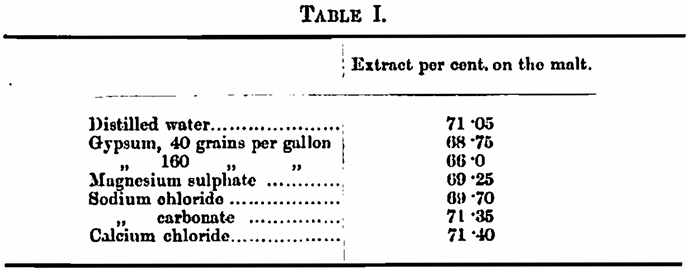

In 1883 E. R. Moritz and A. Hartley stated (J. Soc. Chem. Ind., 1883, 2, 82) that the presence of sodium carbonate tends to lower extracts being obtained. Matthews and Forster, in 1893 (Trans. Inst. of Brewing, 1893, 6, 179), published a series of experiments, in which they mashed a malt with solutions of various salts, and also with distilled water.

The saline solutions used were as follows: — Gypsum (CaSO4, 2H2O), 40 grains per gallon and 160 grains per gallon (saturated solution); magnesium sulphate (MgSO4,7H2O), 20 grains per gallon; sodium chloride, 20 grains per gallon; sodium carbonate, 10 grains per gallon; and calcium chloride, 20 grains per gallon.

In the authors’ own words “50 grams [of malt] moderately finely ground in a hand mill were mashed with 120 c.c. of one or other of the liquids mentioned to give an initial temperature of 150° F., kept in a water-bath at this temperature for 2½ hours, filtered and sparged at 160° F. with the liquid corresponding to the experiment till 250 c.c. of filtrate wore obtained: correcting the specific gravity …. for the added calcium sulphate.” Apparently, the authors considered the specific gravity of the other solutions was small enough to be neglected. The results obtained were as follows: —

The differences are quite marked—in the case of the saturated solution of gypsum 7 per cent, of the extract obtained with distilled water is lost—but as the method employed was one which presents but little claim to giving accurate, or even comparable, results we need not delay over them.

In 1902 Windisch and Hasse (Woch. f. Brau., 19, 339) made comparative mashes with distilled water, with a brewing water containing 52 parts of solids per 100,000, with a hard water containing 111 parts of solids, and with a saturated solution of gypsum. Four different types of malt were used. In all cases, with one exception, the gravities of the worts obtained by means of the mineralised waters were higher than those prepared with distilled water, but the differences in the specific gravities of the worts were in no case so great as the differences in the specific gravities of the waters.

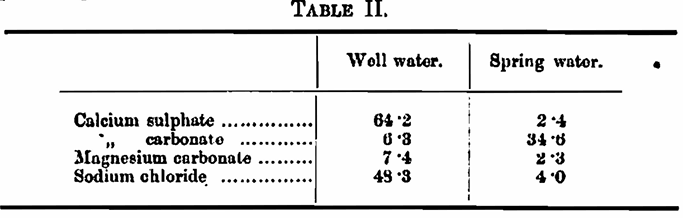

In 1906 Pankrath (Zt. ges. Brauw., 29, 680; see this Journal, 1907, 13, 200) compared the laboratory yields of extract obtained with two brewing waters with those yielded with distilled water. The waters were a gypseous well water and a spring water. They had the following composition per 100,000: —

Samples of Pilsener and Munich malts were used. With the well water, that is the gypseous water, the yield of extract was always higher and on an average 1·7 per cent, higher than that obtained with distilled water, whilst with the spring water the reverse occurred, the distilled water giving about 0·7 per cent, more extract. It is recorded with regard to the yield of extract obtained in the brewery that it was found that in the case of the gypseous well water the laboratory yield was always attained, and sometimes exceeded, whereas, with the spring water, the yield of brewery extract was less than the laboratory extract.

As comment upon this I would only remark that Pankrath appears not to have made any correction in his extracts for the gravity due to the salts in the mashing liquor. He also used a water showing temporary hardness, un-boiled, in his laboratory experiments and compared the results obtained with those found in the brewery, where one may presume, I think justly, that the water was boiled before being used as mashing liquor.

My attention was first directed to this matter by a controversy into which I was led with a friend as to the extract yielded by a particular malt—it was before this Institute had established standard methods of malt analysis. In the discussion of our methods, it was found that one of us made his mash with distilled water, whereas the other used tap water. Experiment showed us that we agreed satisfactorily when we both used distilled water, but that with our tap waters each obtained a different degree of divergence. From time to time some further experiments were made on the subject, and these supply the theme of the present paper.

In all the experiments, without exception, that are referred to in what follows, the Institute’s standard method was employed except that, as stated, water other than distilled was employed.

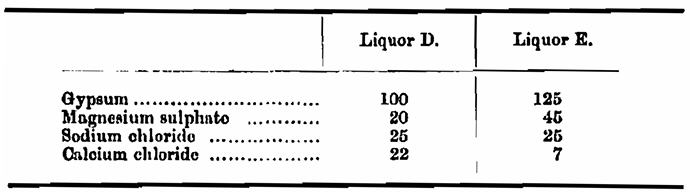

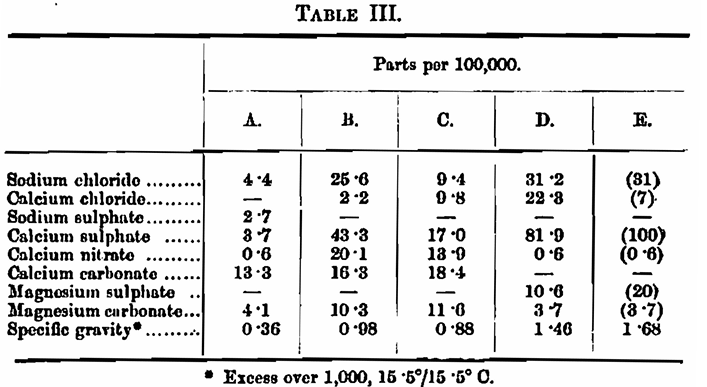

I had at hand distilled water, three well waters, distinguished respectively as A, B, and C, from deep bores, and two treated waters made by dissolving gypsum, calcium chloride, magnesium sulphate, and common salt in different proportions in water A which had previously been boiled. The salts were dissolved in the following proportions per 100,000 of water: —

In the experiments the well waters were always used un-boiled except in the one instance which will be pointed out. The waters had the following composition. Unfortunately, no analysis of the water E was made, but the salts added would give it approximately the composition given: —

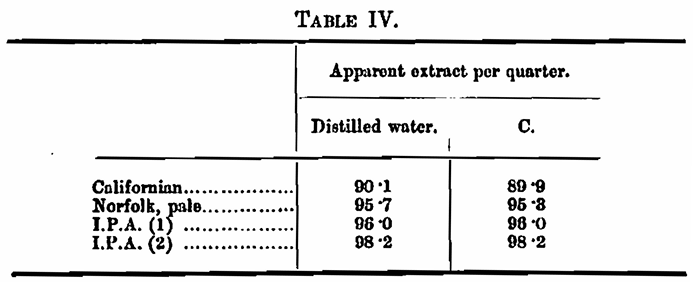

Experiment 1. — The extract yielded by four malts was determined with distilled water and with water C. The results were as follows: —

This looks like pretty good concordance, but really is only an example of accidental agreement, for, as is seen in Table III, water C has a specific gravity of its own, which in the experiment is masquerading as malt extract. As you all know, the extract of a malt is calculated by multiplying the excess gravity of the wort, obtained under standard conditions of dilution, and so on, by 3·36; so that the specific gravity of the water is being returned as 3·36 times as much. malt extract. Let us make the correction: —

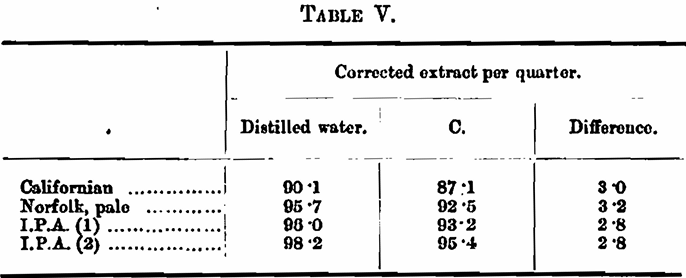

Experiment 2. — A malt was mashed with distilled water and with waters A and E, the extract was found to be as follows: —

It is noteworthy that, in the case of hardened water E, the apparent extract yielded by the malt is 2·6 lbs. above that obtained with distilled water, but when the specific gravity of the water is deducted this gain of 2·6 lbs. is transformed into a loss of 3·1 lbs.

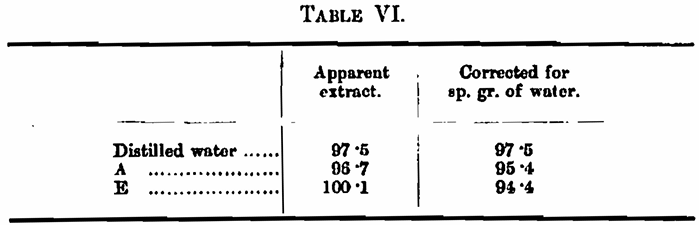

Experiment 3. —A malt was mashed with distilled water, waters A and B, and the hardened water E.

Here the differences, although rather more marked, are of the same order as those in Experiment2, and show that they are not accidental but constant in direction. I will only give the results of one more experiment, which was carried out for me by Mr. Newman, and for which I wish here to express to him my thanks.

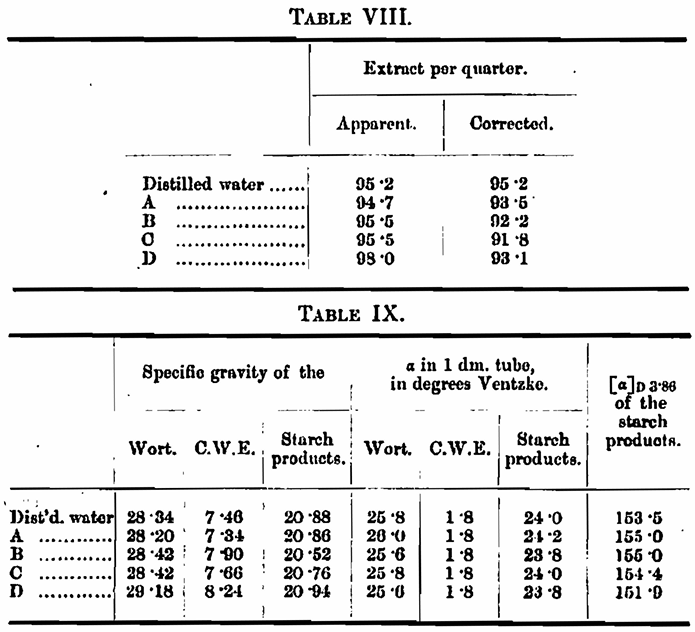

Experiment 4. — A malt was mashed with five waters, and the extract determined in each case. The cold-water extract was also determined with each water. The specific rotatory power of all the worts and cold-water extracts was taken, and from the difference the [a]D 3·86 of the starch conversions was calculated.

We can also from the specific rotatory power of the starch conversion products calculate the ratio of maltose to dextrin in each of these worts by making use of Horace Brown’s generalisation that the products of the degradation of starch by diastase can be expressed in terms of maltose and dextrin.

We thus see, as originally shown, I believe, by Moritz, and again recently by Fernbach, that the composition of the starch conversion is modified by the water used. But it would appear as though, contrary to what is usually stated to occur, in this particular instance the most highly gypseous liquor has led to the production of the greatest proportion of maltose.

It appeared of interest to see if one could find a reason for this variation in extract yield and in composition of wort. The well-known inhibitory action of alkalis upon diastatic action suggested that the reaction of the waters might offer some explanation, and these were therefore determined; 100 c.c. of water was titrated with N/10 acid, using methyl orange as indicator. The results are given in terms of cubic centimetres of acid to avoid converting them into terms of some conventional alkali present, as both calcium and magnesium carbonates contribute to the alkalinity.

The waters, apart from the distilled water, fall at once into two classes, one having an alkalinity of about twice the other (Table XI). Let us rearrange them in their groups and put the corresponding corrected extract yields and the [a]D of the starch solids against them (Table XII).

The extracts fall naturally into the same classes as the alkalinities of the waters, but the starch solids show absolutely no relation. Too much weight, however, must not be ascribed to these last, as owing to the method employed the errors of observation are of very considerable magnitude.

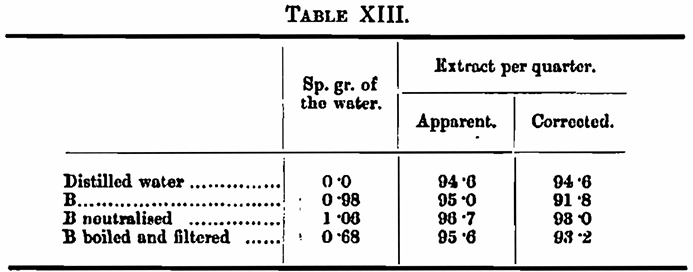

In order to decide whether the alkalinity really was the important factor, a malt was mashed with distilled water, water B, water B exactly neutralised with sulphuric acid, and water B boiled for an hour under a reflux condenser and filtered from the deposited carbonates; 100 c.c. of this required 0·3 c.c. N/10 acid for neutralisation to methyl orange.

This appears conclusive, but it also shows, as the experiments with the “hardened” water had already indicated, that the alkalinity is not the only factor influencing the result, and that the other solids also exert a marked effect.

Let us now pass on to a consideration of the bearing which these experiments have on some of the larger interests which are found outside the walls of a laboratory.

When such a hardened water as the one which we have employed and designated E, having a specific gravity of 1·68°, is used as a brewing liquor, how will it affect the amount of duty levied by the Excise on the brewer’s wort? Wo may take it that in the copper, in the hop-back, and on the cooler, the worts will lose, by evaporation, approximately 20 per cent, of their volume. The saline content will be correspondingly increased, and the specific gravity due to the salts will rise to about the same extent. This means in the instance cited that 2° of gravity will be due to the saline constituents of the wort. Now the Excise charge amounts to l·7d. per barrel at 1° gravity, so that our 2° will cost 3·4d per barrel collected. J. L. Baker, a year or so ago, drew attention to this fact, and went so far as to claim that the specific gravity duo to saline constituents should be deducted from the gravity of the worts before the duty is charged.

There is another aspect of the question. Taking, as a concrete example, the values obtained in Experiment 2; our malt gave an extract of 97·5 lbs. per quarter when mashed with distilled water, and 100·1 lbs. when mashed with the hardened liquor. Of these 100·1 lbs., only 94·4 lbs. were true malt extract, so that 3·1 lbs. (97·5- 94·4) of malt extract were lost per quarter. We can assume that malt extract is worth about 5d. per lb., so that, on this basis, extract to the value of 1s. 3½d. is lost from every quarter of malt mashed. Furthermore, if the brewery is one of those which attain to, or surpass, laboratory extracts, there will be duty to be paid on those 3·1 lbs., or possibly, even, in the limit case, on 5·7 lbs. (100·1- 94·4), which, on our present scale of charges, amounts to 14·6 and 26·6 pence respectively.

In this presentation of the case, the value of the saline ingredients of the mashing liquor, as contributing to the flavour, stability, or other desirable attributes of the beer, has been purposely avoided. This is a question which each one must consider for himself. I have but indicated a view of the question; a view which appears to me to be worth of at least a passing glance.

Discussion.

Professor Adrian J. Brown said they wore much indebted to Mr. Siau for having come forward at short notice to give such a very suggestive paper. The paper had reminded them of the enormous number of important factors entering into the brewer’s processes, and Mr. Siau had called attention to some of those, to which personally he (Professor Brown) had not given the consideration which, apparently, they ought to receive. The subject of the paper required a good deal of consideration before any strong opinion could or should be offered, and it was particularly difficult to consider it apart from those points which Mr. Siau had very definitely expressed a wish to withhold from discussion. He would like to know whether Mr. Siau was quite certain that, in correcting for the gravity in the way he had done in the experiments described, the whole of the gravity due to the salts present in the brewing waters was present in the worts. It appeared possible that some portion might be retained in the grains. If experiments were made to test this, he thought it would tend to strengthen Mr. Siau’s conclusions. There were several points of marked importance raised in the paper which well deserved the attention of the brewer.

Mr. F. L. Talbot thought that Mr. Siau was right, from his point of view, in excluding other subjects, and only approaching the matter of those salts in their relation to extract. At the same time, the subject was very intimately connected with other questions. The sole object of the brewer was to obtain a palate of one sort or another, and, provided the salts had produced a fuller palate, although the brewer was paying something in duty for what was in itself nothing at all, yet, if the brewer attained his object in making the beer more luscious, more-full, more-dry, or anything else that he wanted, or that his customer wanted, that was the real thing that was desirable. That was the question which was always coming up in one way or another. First it came as a question of the qualities of the worts, as to whether they were more dextrinous, or whether there was sufficient maltose in them; then in relation to the attenuation of the worts, whether a wort which was attenuated to too low a specific gravity would produce as luscious a beer as one which remained at a higher gravity. This must remain the important part of the present subject, and it was one to which their attention as brewers could not be too much directed. The consideration of those points was all to their advantage. It would be a very happy thing for them if they could, upon the suggestions made, go to the Excise authorities and say: “Here we have these salts in the beer, please allow us a rebate on them!” He was afraid that day had not yet come. There were many things that the Excise could do to help them, but, unfortunately, the one aim seemed to be how much they could screw out of them. Any subject that attracted their attention as to what they were paying to the Excise, and what they were getting from their malt, was worth consideration.

Mr. W. R. Wilson thought that few brewers realised the large diminution of malt extract which was caused by hardening their brewing liquor. It was important that they should look into the question carefully, and assure themselves that they were fully justified in causing loss of malt extract, in order that they might obtain a brighter and more palatable beer. The chief evidence that bettor beer resulted from hardening liquor seemed to consist of general experience, but, in a matter of this sort, general experience should not be lightly put aside. Mr. Siau had suggested that the loss of extract was due to the alkalinity of the water. But he did not explain why he thought alkalinity should affect the extract.

Mr. Walter Scott said that, although he did not wish to criticise the paper, he would like to make some remarks upon it. The question of the saline constituents of brewing water was one which most brewers had to consider at some time or other. They were especially interested in the chlorides, because there was a stated limit for sodium chloride, and brewers generally endeavoured to fall in with the views of their local medical officer of health when that gentleman chose to define the quantity that should not be exceeded, although they fully realised that it would be a very difficult matter, in case of a prosecution, to differentiate by analysis between sodium chloride and the other chlorides contained in the beer. Brewers who wished to be on the safe side in this matter had therefore been compelled to study the question of the saline constituents of their water, and had doubtless recognised that these salts, if present in excess, meant considerable extra Excise duty in consequence of the gravity they produced. But Mr. Siau had that evening shown them another Aspect of the matter, in that his paper had proved that the saline constituents not only produced gravity themselves, but by their presence actually prevented the extraction from the malt of extract which it was possible to obtain with a softer water. This was an important point and, he ventured to say, one that had escaped the attention of many brewers, but it was also a question which had to be considered in conjunction with the quality of the beer as well as the quantity.

Mr. F. M. Maynard said that all practical brewers must be very grateful to Mr. Siau for bringing the subject before them. The paper reminded him of one he had heard read in Berlin a month or two ago by Professor Windisch, but in that it was boldly stated that every good drinking water was also a good brewing water, and that such constituents as nitrous and nitric acids, ammonia, and sulphate of soda, which they in England credited with detrimentally affecting their produce, had very little influence on the resulting beers. Further, the necessity of the presence of the salts of calcium and magnesium was denied, whilst the most injurious saline matters were said to be the carbonates, not only on account of their neutralising effects, which restricted enzyme action both in the malting and mashing processes, but also on account of the darker colour imparted to the beers in their presence. In breweries where highly carbonated waters had to be used, an indirect acidification of the mash had been resorted to with much benefit, this being most conveniently effected by bacterial action brought about by means of the acidifying Bacillus Delhiicki. It was not stated, however, whether the acidification of the mash helped to increase the ultimate extract, although, if it stimulated enzyme action, such would probably be the case.

The Author, in reply, said that the remarks made followed rather closely upon his own concluding words: — “In that presentation of the case, the value of the saline ingredient in the mashing liquor as affecting the stability or other qualities of the beer had been purposely avoided.” That was the question he must leave each one to consider for himself. He had merely indicated a view of the question which he considered to be worth, at least, a passing glance. The object he had in view in bringing forward the experiments was to ascertain from the members whether the subject was worth consideration. There had been for a long time in this country an idea of the vast importance of the saline constituents of mashing liquor. On the Continent, on the other hand, as Mr. Maynard had pointed out, an opposite view prevailed. Of course, some of them in England were of opinion that there was no such thing as real beer brewed on the Continent. But if they thought Continental methods and beer were worth consideration, then, perhaps, the whole subject of the saline constituents of the liquor might be worth considering. If the salts did nothing, why put them in and pay for them? But if they did something, by all means let them be used. They would be worth the duty. That was the whole point. From what he could gather, some people seemed to use salts with a fairly liberal hand. They put in quite 100 grains to the gallon of the gypsum. Professor Brown had questioned the fairness of the correction made by deducting the specific gravity of the water. Probably the only malt salts affected would be the phosphates. phosphate of lime, it would not be the total phosphate present that Assuming that one precipitated phosphate as was precipitated. The acidity of the malt was made up of the balance of the phosphates; one of these was precipitable as calcium phosphate and the other was not. Therefore, they would not get the whole precipitated. The total amount that went into solution was small, and if 50 per cent, of that were precipitated, it would not amount to much. The point was considered, and some experiments were started on those lines to see what the amount was, but as the time at his disposal was limited, these could not be completed. The first of Mr. Talbot’s questions was important. Mr. Talbot wanted to know whether he was right in leaving out the question of palate. He had not neglected or overlooked it, he had simply not dealt with it there. That was the other side of the question, which he devoutly hoped would be dealt with by someone more capable of dealing with it than he was. With reference to Mr. Wilson’s question, as to how the alkalinity reduced the extract and the maltose and dextrin, he might say that in one experiment he determined the amount of maltose and dextrin present in the worts. The maltose varied in the experiment malts from 67·4 to 72·3, a difference of 5·1 per cent. The difference in the solution gravity of maltose and dextrin would not account for the difference of gravity found. The reason of the loss of gravity he considered to be due to the alkalis, which changed the reaction of the medium, and, as Ford and Guthrie had shown, restricted the diastatic conversion of the starch. An attempt was made to determine the residual starch, but the one or two experiments made did not seem to promise much. A question was asked by Mr. Maynard about the acidification of the mash by a lactic organism. He (Mr. Siau) did not know anything about the effect that would have on the extract yield. It seemed to him rather a roundabout way of doing it. If one wanted to neutralise the water, it was always possible to do it by judicious addition of a quantity of acid, less than sufficient to neutralise the whole lot, so as to be certain to be on the right side. As regarded alkalinity being due to carbonate of lime, that was the substance which usually produced the alkalinity of potable waters. The acidification of the mash, he understood, was a common practice in the distilling industry.

Mr. T. H. Pope said that they actually acidified with sulphuric acid. By that means they produced more spirit.

The Chairman (Mr. R H. Evans), in proposing a vote of thanks to the author, said it was at very short notice that Mr. Siau stepped into the gap, and therefore they were all the more obliged to him for his kindness in helping them out of a difficulty.

The vote was seconded by Professor Adrian Brown, and carried unanimously.

Addendum. — Since the foregoing was read, my attention has been drawn to a paper by J. L. Baker and H. F. E. Hulton in this Journal, 1910, 16, 332, which covers, far more adequately, the ground traversed by me. It was this paper that I had in mind when I referred to Baker having suggested the deduction of the specific gravity due to salts from the observed gravity on which the Excise charge is levied, but I regret that, in the time which could be devoted to preparing the paper, I did not refer to the original, which would have rendered unnecessary the continuance of my task.

R. L. Siau